Having traveled in all fifty states, I must admit there are certain areas of this great country that continue to draw me back, time and again, to enjoy their natural beauty, pleasing climate, and their historical sites. The most fascinating place I’ve traveled is the tiny village of Barrow, Alaska, the northern most of cities in the United States. However, it’s the Chautauqua Institute located in western New York state that continues to garner our return visits each year. Where else can one find such an array of renowned speakers from the arts, education, religion, and politics? And at night you can be entertained by the likes of the Beach Boys, Smothers Brothers, Kingston Trio, The Jersey Boys, The Temptations, The Four Tops, and even Carol Burnett.

But during the summer of 2002, after a short stay in Boston, my wife, daughter and I made a trek to one of the quaint villages on the central coast of Maine. For those old movie buffs that remember the film –Peyton Place – Camden is very much the same village as it was more then 40 years ago when the movie was filmed there. To sit on the tiny waterfront and watch the tall sailing ships gliding in and out of this picturesque harbor is a beautiful and serene sight.

Using Camden as our base, we made day trips to various places in the area. One day we took the ferry boat to the tiny island of Vinalhaven. The island sits just a few miles off the Maine Coast. The ferry ride is very relaxing, and the view of the marine life is breathtaking. Along the way, one can view the lobster boats making their daily runs to their lobster traps that lie in the cold dark waters in this part of the north Atlantic.

Vinalhaven is known for the vast number of granite outcroppings that for generations provided the stone needed to construct many of the granite buildings and monuments in which granite is used as the main construction material. Many of the monuments in the Washington, D.C. area used Vinalhaven granite. Sadly, today most of the island is pocked with abandoned quarries where the easily obtained granite was mined and shipped away. Still there is a thriving community on the island. However, today, the economy isn’t based on the granite industry, but rather tourism and lobsters.

As we sat enjoying lunch in a little organic grocery/deli that overlooked the harbor, I glanced over the shelves that lined the grocery’s walls. I made a mental note of the various products that were displayed there. My eyes were drawn to a section that contained a product that brought back memories of my growing up on a rural Alabama farm. As I thought about this product, my mind drifted back to two events that occurred every autumn on our farm.

Each fall, I knew that two events were about to unfold, two traditional mainstays on the farm. The product I was fondly gazing at inspired joyous memories, but instantly this memory was joined by another ritual that I dreaded.

It was with great anticipation that I looked at the fields of sugar cane we had growing on the farm and when the cane was ready to be harvested. Waiting for the day to start cutting the cane and hauling it to the cane grinder located on the old Lindsay homestead site, this was a delight all the kids in the community could hardly wait. The grinder sat there all year-round under the chinaberry tree waiting for the next fall harvest to start.

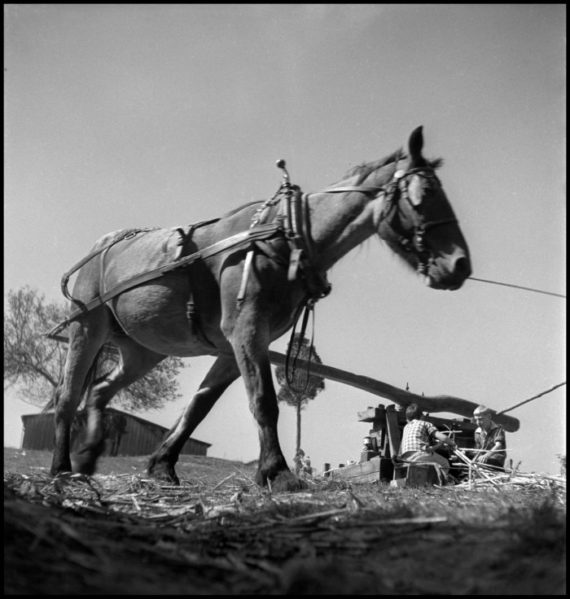

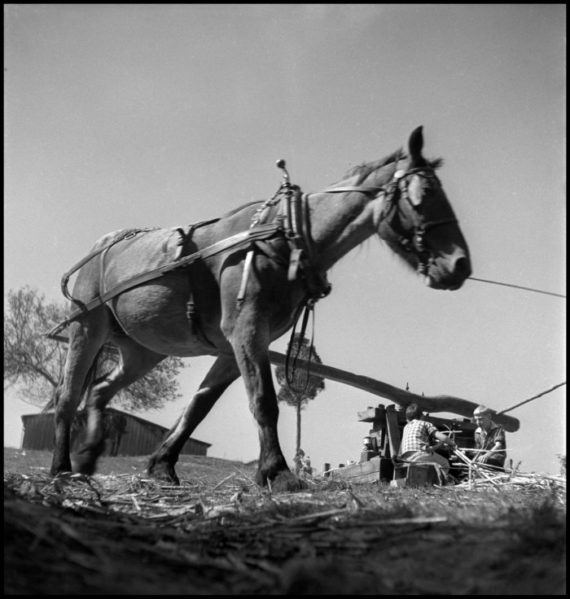

For all the kids in the area, it was an eagerly awaited sight to see Daddy and the farm workers getting the grinder ready for squeezing the sweet nectar from all those stalks of cane. Watching them get out the grease buckets to oil the grinder, we knew our little bellies would soon be filled with what must have been about a gallon a day of the flowing juice churned out from the grinder. A grinder that was being powered by a mule, as one of the farm mules was harnessed to a long pole that as the mule walked around and around, it operated the press part of the grinder.

The juice was supposed to run down a trough into a catch vat, but Daddy always let us kids hold our little metal cups to catch some of the juice as it flowed down the trough – if we stayed out of the way of the plodding mule.

Momma took whatever was left from our skimming and from that she would make our annual supply of sweet cane syrup. Once the syrup was made, Momma would store it in metal cans, assuring us a supply that would grace her biscuits and pecan pies for a full year. And, as always, she supplied all our neighbors and workers on the farm with their yearly supply.

Ah, that sweet nectar! And all the visits to see Dr. Simonton, the local dentist, for so many of us farm kids who had tin cups to catch the sweet over flow of pure sweet sugar.

But there was the other event that took place each fall, just as the first frost came to south Alabama.

With the first frost, I also knew it was time for the ‘hog-killing’ ritual. The frost was the catalyst for the women in the community to gather up their work tables and move them into our backyard. From these tables the processing and making sausage would be done and the carving of the rest of the hog carcass into other cuts of pork.

At the same time as the women’s preparation, the men began the construction of the gallows. These were made from young saplings cut from the nearby copse of woods. From the elevated gallows, the slaughtered hogs would be hung after they had been dunked in scalding vat of water where this would make the removal of their skin and hair being much easier.

The other part of the preparation process involved hauling in loads of hickory wood from the nearby forest. This wood was placed by the wooden smokehouse we had there on the farm. In this smokehouse, our annual supply of bacon and other cuts of pork would be cured with hickory smoke that billowed out of the smokehouse. The smoke filled the air for days and could be smelled for miles around.

I will spare those of you (including myself) who have weak stomachs. This annual ritual and the gruesome aspect of this event took place in our backyard and other backyards across the rural south as late as the 1950’s. It would suffice for me to say, if you ever watched sausage being made, you would never eat sausage again. Never!

The only thing positive about this process was that I was probably the only kid in hundreds of miles in radius from Abbeville, Alabama, who had a swimming pool in the 1940’s and 1950’s. My Daddy’s ‘hog boiling’ vat was made of cast iron and was large enough for me to use it as my personal pool. It wasn’t big enough for swimming laps, but on a hot July day it was the perfect lounging area, as long as the pecan tree kept the vat in the shade.

But as I sat there that day in Vinalhaven, my eyes were fixated on the jars of cane syrup sitting there on the shelf. I got up from the table and walked over and picked up a jar of the sweet liquid. As I read the information on the label, I was jolted back to reality. As with most childhood memories for those my age, the memories of simpler times we cherished in our society have changed. Those memories are fleeting as we remember old customs and how we have discarded them. We can recite the constant excuses why we don’t have time to do these things. We will do it next year! Always another time. Maybe tomorrow! But always later! But tomorrow never comes —–!

The label on the jar of cane syrup said, “Product Made and Shipped from Paraguay.”