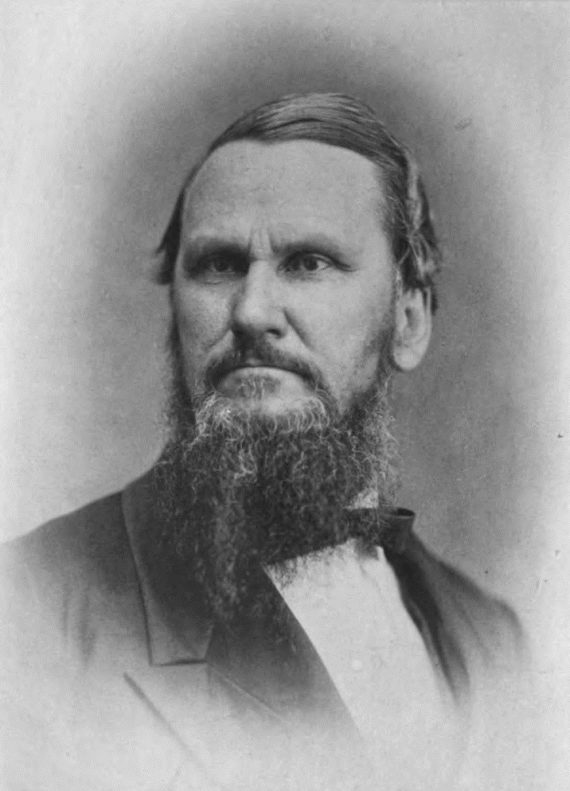

In his 1903 book, The Life and Letters of Robert Lewis Dabney, Thomas Cary Johnson wrote of his friend, colleague, and spiritual brother, “Dr. Dabney was a great man. We cannot tell just how great yet. One cannot see how great Mt. Blanc is while standing at its foot. One hundred years from now men will be able to see him better.”

This prophecy has undoubtedly proven true for those who have been privileged to read any of Dabney’s works, or who have been inspired by his example. His intellect and industry were nearly singular. For most of his vocational years, he was a professor at the Union Theological Seminary in Virginia, where he labored diligently to raise up the next generation of Christian pastors, in not only the nurture and admonition of the Lord, but in a zeal to preach the Gospel to a perishing world. But Dabney was endowed with a broad and keen intellect and a passion for many labors, and his industry extended well beyond the seminary. He was not only a professor, but a pastor and a preacher; a church architect; a prolific author; a Confederate army chaplain; and, during a critical season of the War for Southern Independence, the adjutant general to General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. After many years of faithful labor in his home state of Virginia, Dabney was appointed the first professor of moral and mental philosophy at the University of Texas at Austin. He spent his final years living on the incompletely tamed frontier of the Lone Star State. Dabney’s industry continued until the end.

At the end of his days, Dabney left a wealth of writings to future generations. His Life and Campaigns of Lieut.-Gen. Thomas J. Jackson (1866) and A Defence of Virginia (1867) are still widely read, especially among students of Southern history, and likely represent his most recognizable works. Perhaps only slightly less well-known is Discussions, a five-volume compilation of essays, reviews, sermons, letters, and poetry (1890, 1891, 1892, 1897, 1999). Less broadly read, but magisterial, is his Systematic Theology (1878), drawn from extensive lectures he delivered to the students of Union Theological Seminary. Dabney’s sagacity and polemical might are distinctly exhibited in this work, as they also are in The Sensualistic Philosophy of the Nineteenth Century Examined (1887) and The Practical Philosophy (1897). These writings, along with others unmentioned, are filled with penetrating insights and exhortations for the Church and the South. Dabney has often been deemed prescient, for well before others, he warned of the inevitable cultural decline and ruin that would attend the embrace of progressivism, egalitarianism, state-driven education, and other pestilences. And indeed, his warnings have proven well-founded.

Dabney the conservative; Dabney the scholar; Dabney the warrior. It is likely that these images are familiar to those who have encountered his works. But any work, though reflecting something of the inner life of its creator, does not subsume it. Dabney was all of these things, but he was so much more. Partially concealed behind the noble sentiments of his books, essays, and sermons is a man whose unwritten life is even more eminent, especially given the hard providences he was called to endure. For the duration of his Christian life, he maintained an acute awareness of God’s provision–a benevolent provision. It was a belief in divine providence that sustained him through the seasons of grief. And those seasons were many.

Dabney was in his early twenties when he experienced his first major health malady: dysentery. In its wake, he developed severe and refractory biliary colic. These ailments were debilitating, even to an otherwise healthy young man. In 1847, while suffering under the burden of the latter and laboring as a missionary in his native Louisa County, Virginia, he encountered his mother’s former physician, Dr. William Meredith, on the road. Dr. Meredith was convinced that the usual “calomel and opium” stood no chance of curing him and advised him to be removed to a different climate: “You must get into a region entirely free from malaria, and drink limestone water.” The specific region Dr. Meredith had in mind was Staunton. Dabney answered that although he appreciated the advice, he was aware of no pastoral opening in the region. Resigned to continued suffering, he said, “I might as well expect to marry a princess.” However, a short time later, Dabney was surprised to hear he had been invited to preach at the Tinkling Spring Presbyterian Church, very near Staunton. During his visit, he drank the limestone water recommended to him and experienced no symptoms of colic. Shortly thereafter, he was called to the pastorate of the church. In a later time, he counted this as the providential loving-kindness of God. Quoting the minister Matthew Henry, he said, “He that notes providences shall have providences to note.”

But a much harder providence was approaching. In the fall of 1855, Dabney and his family were met with a visitation that was all too common in those days: diphtheria. The first to be afflicted was his six-year-old son Bobby, who fell ill while his father was away. Robert Lewis rushed to his side and only shortly thereafter found that his second son, five-year-old Jimmy, was also manifesting symptoms of the awful disease. Jimmy succumbed first. Within three weeks, while the wound of his death was still smarting badly, Bobby also died. Robert Lewis and his wife, Lavinia, lived with the daily dread that their infant third son, Charley, would also fall ill. Lavinia contracted diphtheria herself. But by the grace of God, she recovered and Charley’s health was spared.

Of these devastating losses occurring in such quick succession, Dabney wrote to his brother:

It is painful to me to write to my friends now, delightful as it is to receive their communications. I cannot speak of anything except that which fills my mind every waking hour, except when I drag it away to my daily occupations, my two boys gone from me; and yet it is painful to speak of them, too. When my Jimmy died, grief was pungent, but the actings of faith, the embracing of consolation, the conception of all the cheering ring truths which ministered consolation were proportionably vivid; but when the stroke was repeated, and thereby doubled, I seem to be paralyzed and stunned. I know that my loss is doubled, and I know also that the same cheering truths apply to the second as to the first, but I remain stupid, downcast, almost without hope and interest.

Still he retained his trust in the God who works all things together for the good of those who love Him. Later in the same letter he wrote, “But thanks to God, I am not moping nor murmuring. If I could see the blows blessed to myself, my kindred and my friends. I should in time be able to bless God for it; and this is my constant prayer.” One of Dabney’s students, who saw him in the depth of despondency over his departed sons, later attested to his teacher’s unshakable conviction of God’s lovingkindness: “In his prayers, thereafter, in class-room and chapel, his pupils felt and saw, what is to be but rarely seen, how one of the most imperial of human wills may humbly bow, pass under the rod, and caress with filial affection, the fatherly hand that chastises.”

Over the next several years, Dabney suffered from recurrent fevers and respiratory illnesses, but remained steadfast and regular in his teaching and preaching. This steadfastness served him well in the winter of 1860-61, as the storm clouds of war gathered over America and prepared to burst into a tempest. Dabney was assiduously opposed to the North’s sectional agitators, but he urged his fellow Southerners to moderation and restraint and continually prayed and preached for peace. It was Abraham Lincoln’s brazen imperiousness that finally turned Dabney from a Union man to a Confederate man. In mid-1861, Dabney served as a Confederate chaplain for four months, after which an attack of camp fever and the necessity of returning to duties at Union Theological Seminary forced him to retire from the military for a season. In that brief chaplaincy, he had already witnessed much death and illness and had endured the latter himself. In subsequent months, he saw the providences of the seminary decline, as most of the students volunteered for military service, or were conscripted. In a short while, Dabney joined with millions of other Southerners in enduring the privations of war.

The war years saw the passing of his sister, Betty, who died in his arms after a painful and protracted illness–likely tuberculosis. This sister held a special place in his affections. He wrote that her presence in his home had always been like that of an angel: “Peace and light and love seemed to enter it with her, brightening every face….” Her death was a grievous blow to all who knew her, but Dabney found comfort in the wake of her passing, as he considered how she had overcome the ravages of the Great Destroyer and was now tranquil in the presence of her Savior. He later wrote, “Henceforth my best and clearest conceptions of heaven shall be of a society formed of such loving spirits as thou wast on earth, crowned by the presence of the Saviour, whose loveliness they only reflect.” A month after Betty’s death, Dabney wrote to his mother about the recent expiries of other saints, some of whom had been killed in the escalating war:

I have been much humbled and comforted, at the same time, to remember how much the most eminent saints whom I have known and loved were afflicted;… When I look on with envy upon their calm and heavenly old age, and their peaceful death-beds, I am compelled to remember that they were thus ripened for a more blessed world, chiefly by the long schooling of affliction; and I feel that if I may gain such an advantage likewise, at such a cost, it does not become me to repine. It will be labor well spent.

The future still held a considerable labor of suffering for Dabney. In the spring of 1862, General Stonewall Jackson successfully procured him as adjutant general, while still granting him the liberty of a chaplain to preach on Sundays. The former role was unfamiliar to Dabney, and provoked in him a feeling of inelegance. But the latter role was one for which providence had well seasoned him. He preached often, and the soldiers spoke graciously of his sermons. He accompanied Jackson’s army throughout the hard-fought Shenandoah Valley Campaign, and even oversaw the rescue of the Confederate baggage and ammunition train at the Battle of Port Republic (a role he humbly omitted in his own biography of Jackson). Shortly thereafter, he rendered admirable service during the Seven Days’ Battles. Nevertheless, military campaigning proved arduous, and Dabney’s health, which was still enervated from the previous year’s bout of camp fever, foundered under the strain. His camp fever returned with a vengeance and brought him near to death. Pronounced unfit for further military service, Dabney was forced to submit his resignation in August 1862. General Jackson accepted this departure with deep regret, having considered him a capable and dedicated adjutant.

Dabney’s illness was protracted. While he was still convalescing, the destroying hand of diphtheria returned and gripped all three of his sons–two of whom had been born since the disease had last afflicted the Dabneys in 1855. Five-year-old Thomas died and was buried alongside Jimmy and Bobby. This loss caused deep devastation, but Dabney recognized an abiding call to serve at the seminary and was soon back at work. In the spring of 1863, he joined the rest of the South in grieving the death of his friend and former chief Stonewall Jackson. In June, Dabney was enlisted to deliver a memorial sermon in honor of Jackson. He expounded the foundations of Jackson’s moral and martial courage and preached a submission to God’s providence that the general would have vouchsafed.

Now, the child of God is not taught what is the special will of God as to himself; he has no revelation as to the security of his person. Nor does he presume to predict what particular dispensation God will grant to the cause in which he is embarked. But he knows that, be it what it may, it will be wise, and right, and good. Whether the arrows of death shall smite him or pass him by, he knows no more than the unbelieving sinner; but he knows that neither event can happen [to] him without the purpose and will of his Heavenly Father. And that will, [be] it whichever it may, is guided by divine wisdom and love.

Dabney did not speak these words out of balmy optimism. He knew pain. He knew loss. But he also knew the hope of the Christian, who can say confidently, “And we know that all things work together for good to them that love God, to them who are called according to his purpose” (Romans 8:28). For God moves in a mysterious way.

Mrs. Jackson commissioned Dabney with writing a biography of her late husband, a task which occupied him for much of the remainder of the war. But, as the once bright prospects for Confederate independence abated and the shadows of looming defeat grew long, Dabney returned to the battlefront and preached to the soldiers. In the closing months of the war, he opened his home to convalescing soldiers and shared in their charge, even as resources became scarce.

Reconstruction forced new calamities on the South, and the Dabney family found no special respite. The privations of the post-war period were so harsh, and the corruptions of the carpetbaggers were so egregious, that Dabney deliberated emigrating to Australia, New Zealand, South America, or Europe. But the prospects of the seminary and Virginia improved, and he stayed in his native land. Despite the hardships of these years, he was remarkably productive and published some of his most searching works. But the ill health that he had accompanied from a young age continued to afflict him. An aggravation of chronic bronchitis prevented him from attending his mother’s funeral in 1873, and ultimately forced him to relinquish his pastoral call. Still, there were times of celebration and sweetness. Between 1878 and 1880, Charles W. “Charley” Dabney pursued a doctorate in chemistry and mineralogy at the University of Göttingen. This afforded his father an opportunity to visit him, and to behold the noble lands of Latin Christendom.

It was during this European tour that Dabney first knew the pain of sciatica, which would harass him in various seasons for the rest of his life. The days of his middle age were waning. Senescence was leaning upon his body. In 1882, he was burdened more severely than ever with chronic malaria. This episode left him at the threshold of death, and compelled him to write later,

Relations and friends wrote me kind letters congratulating me on my recovery. I sent back polite thanks, but sometimes added: ‘I much doubt whether I am to be congratulated. I had gotten so close to the river of death that all the pain and trouble of crossing over were virtually done with. Friends, in their kindness, pulled me back to life so that I shall have all the trouble of the hard and rough descent to go over again–a prediction that has been fulfilled three times–in 1885, in 1890, and in 1895, with awful suffering, and yet I have not crossed over. What next? I hope that next time God will grant me a quick and easy passage.

But the final years would not be easy for Dabney. His invitation to join the first faculty of the University of Texas in 1883 was providential, as it extended him an opportunity to escape the malarious country in Virginia. But in the wake of malaria came the chronic and nearly intractable miseries of cystitis, bladder stones, and prostate enlargement. These caused him such severe illness that rumors of his death became widespread. He placed his life in the hands of God and ultimately endured this season of suffering. But another, more pernicious enemy was gradually closing in on him: glaucoma. Beginning in 1885, Dabney’s eyesight entered into an irreparable decline. Though he had no confidence that the course of the disease could be reversed, he sought the care of an ophthalmologist in Baltimore to satisfy the entreaties of Lavinia and their sons. But it was of no avail. Dabney’s brother urged him to submit to God’s providence. And indeed he did so for a season, resolving to “die in the harness.” Still, he sought one last medical opinion, and was finally told to abandon the expectation of retaining any vision. Johnson writes of Dabney after receiving this catastrophic news,

He went off alone on the piazza, and there for two hours fought another battle, with himself, for readjustment to God’s providence. The fight was severe, but, by the arms of faith and prayer, by the invincible might of God’s little ones, he won. He returned to the company cheerful and happy. He had recognized the inevitable, and the hand of God in his affliction, and he had formed a new plan of action, and squared himself for the new course.

By 1890, he was completely blind, and he suffered constantly from cystitis. But he maintained his trust in God, saying,

Without the Christian’s hope, such an existence would have been unendurable. But with it, I can honestly testify that my years of infirmity have been far from being years of unmixed sorrow, either by reason of present suffering or the pains of anticipation. I have known always that more or less of acute pain is to be my daily lot, until death ends it; but I have the humble assurance that death will end it, and that then the suffering of this present time shall not be worthy to be compared with the glory that shall follow.

Dabney’s mental acumen was as sharp as ever. Despite his physical frailty, he delivered eighteen lectures at Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary in the fall of 1894, whereupon one of the faculty referred to him as the “prince of teachers.” He continued preaching and teaching publicly, and he consistently impressed his audiences with his intellect and graciousness. He also received letters of commendation and thanks from his former students. But gradually his attention turned to the world to come. In October 1897, as his strength continued to diminish, he wrote to his friend, Henry Stokes, “There are some petitions which will come in every time I pray: ‘Lord, choose the time and mode;’ ‘Lord, make me ready, come when it may;’ ‘Lord, increase my faith;’ ‘O Lord, give me dying grace in the dying hour;’ ‘O Lord, make my children and their children ready.’” Only a few months later, on January 3, 1898, Dabney closed his blind eyes one final time. When he opened them again, his sight was restored in the beholding of his Savior.

Those who have read the works of Robert Lewis Dabney appreciate why he represents what is true and valuable in the Southern tradition. But his intellectual and controversial writings tell only a portion of his life’s story. His life’s labors were marked by courage, patriotism, charity, longsuffering, humility, and above all these, a trust in God’s providence. It was this trust that sustained him through many trials, some of which he endured collectively with his family and the South, and others of which he bore uniquely. His is an example to those seeking to learn how to “wait on the Lord.” So the words on the headstone of the noble Dabney fittingly read:

In unshaken loyalty of devotion to his friends, his

country, and his religion, firm in misfortune, ever active

in earnest endeavor, he labored all his life for what he

loved with a faith in good causes, that was ever one

with his faith in God.

So moving and inspiring. Thank you.

This was a very good biographical sketch of Dabney. I have taught on his life twice in Sunday Schools. I am aware, as I said in my first lesson, Dr. Joe Morecraft was not fond of Sean Lucas’s biography. Like the words of Lynyrd Skynyrd “A southern man don’t need him around anyhow.” However I have often said that I believe Dabney’s intellectual acumen was equal to Jonathan Edwards’s as a philosopher. re: Dabney’s review of Edwards on The Benevolence Scheme, The Practical Philosophy. I needed someone to help me get the gist of some of Dabney’s such writings. It is his “Discussions” that I am continually drawn to. As a teacher of America’s history of revivals, articles like “Spurious Religious Excitements” is one of the most helpful things I have ever read. But it was his strict conformity to the Westminster Confession that makes his theology so helpful in critiquing authors like Horatius Bonar, Charles Hodge, or Breckenridge. And I say that as a Baptist! I only recently discovered the Abbeville Institute so I have a lot of reading to do. My mom is from Louisiana and I believe very strongly that we are being surrounded by history revisionists in our day. I am indebted to you for your research.

I have Dabney’s Systematic Theology. It is good but difficult reading.

I didn’t know about Dabney’s health problems and the deaths of his sons. He went through a lot of pain. Such a time of suffering. Now so many of his illnesses could have been relieved. And the diptheria, a big killer then but now vaccines provide protection. The malaria is a bad thing. Now we take chloroquine or at least that is what I took when in Africa. But over there I saw a case of malaria. It was in Ethiopia. An Australian got it bad. I don’t know if he got lax on taking his preventative meds or what but they carried him out of our compound in Addis Ababa and he looked like a wash rag that had been rung out completely. Malaria would have been enough but Dabney has so may illnesses. That must have been trying.

The article was quite moving and well written. In a subsequent article maybe the same author will address some of the “controversies.” No great men are without a few.

I trust that Dabney is enjoying the society of his dear sister crowned with the company of our Savior. —KZ

Dabney is at the very top of a select few who I consider most to be admired in forging the Southern Tradition. This article reinforces my convictions of reverence for Dr. Dabney.

Wonderfully written tribute to Reverend Dabney though I wish you had mentioned his service to Hampden Sydney college where he is buried.

Thank you for writing this. It provided timely and much-needed inspiration. I believe history is supposed to introduce us to noble characters and I love that Abbeville consistently acquaints me with people I probably wouldn’t find otherwise.