In April 1861, a public meeting was held in New Orleans, Louisiana to discuss Governor Thomas O. Moore’s call for volunteers to defend the South against the invading Union army as the War Between the States was just beginning. This particular meeting did not consist of white men, however. It was led and attended by what the newspapers called the “free colored residents”, acting in the proud tradition of the men who had followed Andrew Jackson into battle and saved New Orleans from the British during the War of 1812. Over 2,000 men attended.

Prior to the meeting, a group of these men had published a series of resolutions and signed their names to them, men such as Armand Lannusse, educator, and poet; Louis Golis, Florville Gonzales, Joseph Lavigne, and others. They declared “… the population to which we belong, as soon as a call is made to them by the Governor of this State, will be ready to take arms and form themselves into companies for the defence of their homes, together with the other inhabitants of this city….”1 Lanusse and the others led the meeting on April 23, 1861 during which 1,500 of the “flower of the free colored population” signed up to volunteer for Louisiana’s military.2 These men offered their services to the Governor and were accepted, an action which was widely covered and widely praised by the local press, and noted by some newspapers in the North as well. Jordan Noble, the “Drummer of Chalmette”, who as a teenager had played the drum for Andrew Jackson’s army in 1814-15, was one of the more well-known men who were busy raising a company of black soldiers. The combined group was designated the “Regiment of Native Guards”, as seen in orders addressed to the 1st Division Louisiana Volunteer State Troops by John L. Lewis, Major-General Commanding3. Felix Labatut, a respected citizen, and a signer of Louisiana’s Secession Ordinance was appointed as their colonel.

As a part of the 1st Division Louisiana Volunteer State Troops, the Native Guard participated in many of the same activities as the other Volunteers in the same division. The 1st Division held several inspection parades, observed the 4th of July at Camp Lewis, attended the funeral of several officers who had died and were sent to New Orleans for a burial, and observed the anniversary of Louisiana’s secession from the United States. They drilled and received flags, and at some point, Jordan Noble’s Plauche Guards may have become independent of the larger group.

If the person curious about the Native Guard does some reading about them, either in books or online, there is a claim that will be found in many accounts. The Louisiana legislature revised the State’s militia law early in 1862, supposedly forcing the Native Guard to disband, until the Governor called them back into service. The following are typical accounts:

– “The Louisiana State Legislature passed a law in January 1862 that reorganized the militia into only “…free white males capable of bearing arms… ”

The Native Guards regiment was affected by this law. It was forced to disband on February 15, 1862, when the new law took effect. “Their demise was only temporary, however, for Governor Moore reinstated the Native Guards on March 24 after the U.S. Navy under Admiral David G. Farragut entered the Mississippi River.””4

– “In January 1862 the Louisiana State Legislature passed a law that required militia members to be white. On February 16, 1862, the 1st Louisiana Native Guard was disbanded.”5

– “…. their service proved to be short-lived owing to legislation that limited membership in the state militia to “free white males capable of bearing arms.” The unit disbanded but was reformed in response to the presence of United States naval forces under the command of Admiral David G. Farragut, which appeared at the mouth of the Mississippi River in April 1862.”6

– “The legislature’s reorganization of the militia also affected the Native Guards. Because the new statute specified white males and disbanded all militia units as of February 15, 1862, the Native Guards ceased to exist on that date.” 7

Are these accounts accurate? A fair reading of these four examples and many others would lead the reader to conclude that the racial requirements of the new militia law resulted in the Native Guard becoming an illegal black military unit and thus being forced out of existence, until Governor Moore, desperate for men to defend New Orleans in the face of the approaching Federal fleet, called them back into service and disregarded the law.

Did the Native Guard disband on February 15, 1862? Yes, they did, and so did every other State military unit in Louisiana, in order that they could immediately re-form in conformity to the new law. The circumstances were not about race, as the writers quoted above have painted them, though it is fair to point out that James Hollingsworth does recognize that all militia units were disbanded, not just the Native Guard, a fact the other three sources fail to mention. A notice to the volunteer organizations explaining the effect on them of the new law was published in the New Orleans Daily Crescent, dated February 11, and it began with the following:

The Commander-in-Chief and Major General elect, in order promptly to put into operation the new Militia Law, desire to explain to the Volunteer Companies of the City and State, and all persons disposed to form Volunteer Companies, the character and effect of the law.

1- All the present Volunteer Companies, Battalions, Regiments, Brigades and Divisions, are disbanded by operation of law, on the 15th day of February, 1862.

2 – Volunteer Companies, Battalions, Regiments, and Brigades, in the Parishes of Orleans and Jefferson, may be formed so as to be put into immediate operation.8

To repeat: every existing State military unit was disbanded, not just the Native Guard. This was a military organizational revision, not a racial cleansing of the militia and volunteers. That alone is not evidence that the Native Guard did not disband and stay that way while all the other volunteer organizations reformed, but there is other evidence to consider.

There was, of course, a militia law already on the books when the free men of color volunteered and were accepted in April 1861. It was passed by the Louisiana legislature in 1853, and I wonder if any of the authors cited above bothered to take a look at it before concluding that the 1862 law removed the Native Guard from service. That was one of the first questions that occurred to me: if the new law removed them from service, what did the old law say? To my surprise, the racial requirements were identical in both laws.

The 1853 Louisiana Militia law, Section 1:” …That the Militia of the State of Louisiana shall be composed of all free white males residing in the State, and who have resided there sixty days, and are eighteen years of age, and not yet forty-five, and who are not exempt under the laws of the United States or of this State.”9

The 1862 Louisiana Militia law, Section 1: “… That the Militia of the State of Louisiana shall be composed of all the free white males capable of bearing arms residing in the State, and are eighteen years of age and not over forty-five, and who are not exempt under this law.”10

In other words, the racial requirements for the militia did not change when the law was revised. The entire time that the Native Guard was in existence as a military unit, the militia law specified free white males between 18 and 45. If the law in place specified white males only when they volunteered and were accepted, and that did not prevent them from becoming Louisiana soldiers, why would the revised law force them to disband? Were they an illegal regiment the entire time?

Historian Arthur Bergeron does not make the same assumption as the writers quoted earlier. He mentions nothing about the Native Guard being disbanded in his essay “Louisiana’s Free Men of Color in Gray.” Bergeron does note something these other writers do not mention. “Under an act of the state legislature reorganizing the militia, Governor Moore renewed the commissions of the Native Guards’ regimental field and staff officers as well as those of the officers of the Plauche Guards on February 15.”11

The date does not quite line up with records which can be found on Fold3, but Bergeron is correct when he writes that the officers were recommissioned. Felix Labatut’s card states that he was “elected or appointed” Colonel of the Native Guards Regiment on February 15, 1862, the very date his command supposedly ceased to exist. How exactly could he be made the Colonel of a non-existent regiment? Labatut’s commission was later issued on March 13, 1862, ten days before the March 23rd order that supposedly brought the Native Guard back into existence. His second in command, Henry Ogden, was elected and his commission issued on the same dates as Labatut. The same was true of George Urquhart, a lieutenant in the Regiment of Native Guards. He too was elected on February 15 and was issued his commission on March 13. Officers elected by or appointed to non-existent regiments make no sense. Volunteer companies had the privilege of electing their officers, which would place the election of both Colonel Labatut and the other officers by the men on February 15th within the newly established regulations for choosing officers, but obviously there had to be men present to vote.

Volunteer Companies, Battalions, Regiments and Brigades may determine the mode of electing or appointing their officers. Any mode by which the sense of the Company, Battalion, Regiment and Brigade may be ascertained, will be sustained, whether by resolutions, viva voce vote, or ballot.12

The returns had to be sent to the Major-General, who would certify and forward them to the Governor, who would then issue the commissions. This makes clear why it was nearly a month later before Labatut and the others were commissioned. The entire Louisiana military was rebuilt in a very short time, and every unit needed their officers recommissioned. There were other officers recommissioned later than Labatut. Clearly these duties took some time on top of Moore and Lewis’s other responsibilities.

There is more direct evidence of Native Guard and Plauche Guard activity after February 15 than the reelection of their officers. During much of 1861 and early 1862, Louisiana newspapers would publish military notices. Some units who took advantage of this included the 2nd Brigade Louisiana Volunteer troops, the Beauregard Regiment, the Crescent Regiment, the British Guard, and many other of Louisiana’s military organizations. These groups would publish orders from their commanders, publicize drills, solicit recruits, or offer a $50 enlistment bounty. These would appear in both English-language newspapers like the New Orleans Daily Crescent, and French-language newspapers like the New Orleans Bee/ the L’Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans. And if nothing else presented so far was available, an order for the Native Guard that appeared in the February 15 Bee should put to rest the claim that they were disbanded by the new law. Henry Bezou, adjutant major, gave the “Regiment des Native Guards” these orders, translated from French:

Special Order No. 1 – In accordance with the ordinance from State headquarters, the various companies will meet, and at the end of the evening proceed to the reorganization of the said companies, and to elect for the companies a captain, and a first, a second and a third lieutenant. The captains immediately after (the same evening) will select the officers of the companies, five sergeants and four corporals13

The election of officers and the number that are listed are in conformity with the newly passed regulations. The Native Guard were not being sent home and their regiment ended because they were black. They were ordered to reorganize their company just like every other Louisiana military regiment.

Jordan Noble often had orders or notices for the Plauche Guards placed in the newspapers, and one was published on February 15 that clearly indicates he had no expectation that his company was being disbanded and sent home. Pay particular attention to the date and to the final sentence.

Plauche Guards, Attention! The Company will meet, in full uniform, on Sunday Next, the 16th inst., at the Drill Room, corner of Front Levee and Customhouse streets, at 8 o’clock A.M. to receive a Flag that is to be presented by the young ladies, and proceed from thence to the Jesuit Church, on Baronne street, to have the Flag consecrated. Consecration will take place at 1 o’clock; after which a collection will be taken up for the colored orphans. The Company will also meet this evening, at 7 o’clock, to organize under the New Law, in obedience to orders from headquarters. By order J. B. Noble, Captain.14

Those are not the orders of a man who expects to be put out of a job by the new law. And there were other military notices published after February 15 that indicate the Native Guard were still active. The Meschacebe Native Guards, a company within the Native Guard captained by Armand Lanusse, had a notice in a French Louisiana newspaper dated February 20th noting that “La compagnie reprendra ses exercises d’ecole de battallion…” which translates to “The company will resume its battallion school exercises, “… per ordre de capitaine.”15. There is a notice in a French newspaper from Colonel Labatut dated March 15 which is addressed to the “Regiment des Native Guards”, ordering the officers to meet for an important discussion “per ordre de colonel”.16 A disbanded regiment seems unlikely to be under orders and to have a captain or colonel.

To summarize:

- It was not just the Native Guard that disbanded on February 15, 1862. It was the entire Louisiana military; the Guard were not singled out.

- The racial requirements of the Louisiana militia law did not change when the new law was passed in 1862, meaning that it makes little sense for the Native Guard to have legally served under the 1853 militia law, but to be expelled from service by the 1862 law when both employed the same language.

- The service records of Felix Labatut and other officers of the Regiment of Native Guards show that they were either elected or appointed on February 15, 1862. Military units that have just been disbanded are hardly likely to be reelecting their commanding officers or to have officers appointed for them.

- Direct orders to the Native Guard to reorganize and Jordan Noble’s orders to the Plauche Guards that clearly show he was also ordered to organize under the new law are direct evidence that the Native Guard continued to exist after February 15, 1862. The orders to the Meschacebe Native Guards on February 20, and Col. Labatut’s orders for a meeting of the regiment’s officers on March 15, 1862, means activity was taking place during the time when it is claimed that the Native Guard no longer existed.

What this shows is that many who have written about the Native Guard have simply not taken the time to find as much evidence as they can before making a claim. Just because a claim is widely circulated and accepted, such as the one that the Native Guard were put out of business by the 1862 militia law, does not make it true.

How many of those writing about the history of this group have taken the previous militia law, the reelection and recommissioning of the officers and the military notices in the newspapers into account? Arthur Bergeron seems to have done so. I understand that modern digital resources make research far easier than it was in the past, but I suspect many modern writers just accept and copy portions of accounts that already exist without doing much research of their own. In some ways that is really the point here, that historical accounts based on incomplete research get passed around from website to blog to books, where they are repeated and come to be accepted as fact, when a little digging would cast some additional light on the situation and might even change our view of the entire scenario. For some writers, determined to always paint the South as all bad, all the time, as long as the Native Guard come across as victims in their accounts, that’s all they are interested in. No further research is necessary. They have written something in conformity to the agenda.

The truth matters. Examine sources. Be curious. Dig into the historical record. Don’t just take a history writer’s word as fact, do some research of your own and ask questions. Don’t assume a writer has thoroughly investigated every source, not even me. Check my sources. You may well find that a lot of commonly held assumptions about events are wrong because key facts are not considered. And though history shows that racial discrimination during this era was very real, and no doubt the members of the Native Guard each experienced their share, there are more than enough actual examples from history that writers should take care not to manufacture more where it did not exist. Historical truth and accuracy should be the goal, not reinforcing narratives.

- “Free Colored Warriors in the Field.” New Orleans Daily Crescent, April 22, 1861

- “Meeting of the Free Colored Population.” Gazette and Sentinel (Plaquemine, LA) April 27, 1861

- John L. Lewis, General Orders No. 23 New Orleans Daily Crescent (New Orleans, La), September 17, 1861

- “1st Louisiana Native Guard (Confederate)” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1st_Louisiana_Native_Guard_(Confederate) Accessed March 22, 2022

- Jackson, Joelle “CSA 1st Louisiana Native Guard (1861-1862)” Black Past, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1st-louisiana-native-guard-csa-1861-1862/ Accessed March 22, 2022

- Levin, Kevin. Searching For Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth. University of North Carolina Press, 2019. p 45

- Hollingsworth, James G. Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War. Louisiana State University Press, 1998. p. 8

8, 12. Thomas O. Moore, Governor and John L. Lewis, Major-General Elect, Notice to the Volunteer Organizations throughout the State. New Orleans Daily Crescent, February 15, 1862

- Acts Passed by the First Legislature of the State of Louisiana, Held and Begun in the Town of Baton Rouge on the 17th January, 1853. Published by Authority. New Orleans, printed by Emile La Sere, State Printer, 1853. p. 347

- Official Copy of the Militia Law of Louisiana, Adopted by the State Legislature January 23, 1862. Baton Rouge. Tom Bynum, State Printer 1862. https://archive.org/details/officialcopyofmi01loui/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater

- Bergeron, Arthur W. “Free Men of Color in Grey.” Civil War History, The Kent State University Press, Volume 32, Number 3, September 1986. Pp 247-255

- L’Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans (the New Orleans Bee), February 15, 1862

- J. B. Noble, Orders to the Plauche Guards. The Daily True Delta, February 15, 1862

- L’Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans (the New Orleans Bee), February 20, 1862

- L’Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans (the New Orleans Bee), March 15, 1862

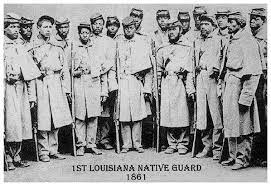

The picture, I’ve seen it posted often on Facebook as a Confederate unit but read that this is a mistake and this is actually a picture of Union soldiers. Is this not the case?

Fake photo, originally taken in Philadelphia

https://jubiloemancipationcentury.wordpress.com/2011/01/04/truth-lies-and-a-black-confederate-soldiers-hoax-and-the-true-story-of-the-louisiana-native-guards/