Until the publication of Jay B. Hubbell’s great The South in American Literature 1607-1900 (Duke University 1954), nobody remembered many of the South’s great writers, apart from Edgar Allan Poe and, if only by deprecation, maybe Joel Chandler Harris. Now nobody remembers Jay B. Hubbell.

Hubbell’s work extends beyond scholarship through antiquarianism practically to archaeology. The chief reason why modern Northern historians have treated Southern writers inadequately, he wrote, has been the difficulty of finding writings that survive only in rare books, magazines, and pamphlets. One rare treasury that we should mention particularly is Thomas Willis White’s Southern Literary Messenger, the magazine that Poe edited and where so much of his own work first appeared. It’s available online now, at last.

But even before the War the Yankees paid scant attention to the literary South. “We do not know sufficiently of the South,” Washington Irving wrote to the forgotten novelist George Higby Throop of North Carolina, “which appears to me to abound in material for a rich, original and varied literature.” Throop’s tongue-in-cheek novel Nag’s Head: or, Two Months Among “The Bankers” (1850), written as Gregory Seaworthy, is the first novel about contemporary life in North Carolina, and his Bertie (1851) is almost as amusing as it is informative about the local culture at the time, but neither can be easily found now.

It’s still surprising that apart from Hubbell there are virtually no bibliographies or critiques or even encyclopedia articles about Southern writers who were, often, far more popular across the Union than many of their Northern counterparts. The lack of biographies is in itself a painful loss. The Southern novelists and poets who wrote our regional epics themselves lived cinematic, often operatic lives stranger than any of their fictions, and none of them fits expectation or stereotype. Well, Davy Crockett wrote more, and funnier, than you think he did.

And there’s Moncure Daniel Conway, the Transcendentalist Abolitionist of Virginia who edited Thomas Paine, chatted with Emerson and Whitman and never forgave Lincoln for starting an unnecessary war. Conway’s own biographies of such notables are rich veins of information untapped, and available nowhere else. From childhood he knew practically every influential figure of the century. His grandfather once took in a threadbare Yankee peddler who’d been thrown out of an inn and let him study in his plantation library. That vagabond salesman, thus educated, went back North to find fame. Today you don’t know Conway, but you undoubtedly know Bronson Alcott.

Washington Allston, the poet and painter of South Carolina, was born to an arranged marriage that exploded while his father was off fighting under Swamp Fox Marion — his mother fainted dead away one stormy night when she recognized the sole survivor of a shipwreck on the beach of their seaside plantation as the lover she’d been told was dead. Allston himself grew up to marry the sister of William Ellery Channing and teach painting to Samuel F. B. Morse, and critics of the stature of Samuel Taylor Coleridge enthusiastically admired his poetry. But while his biographers make much of his art they almost never even mention his writing. Today you can hardly find a verse of it without some pretty extensive excavation.

Philip Pendleton Cooke, related to everybody you can name in Virginia, read Chaucer and Froissart but wrote his lofty prose and poetry only when Poe managed to prod him out of his hard-riding plantation life — he wrote, he said, “with the reluctance of a turkey hunter kept from his sport.” Yet he left us volumes of exhilarating charm before he died at 34 with too much unwritten, having caught pneumonia after wading into the Shenandoah in January to retrieve a wounded duck.

As for the Southern belles of belles-lettres, the situation is just the same. Some historians still refer to ladies’ private diaries like those of Mary Boykin Chesnut, but a female writer of stature who wrote of the South hasn’t a chance of proper regard. Not even the superb blind poet Margaret Junkin Preston of Lexington, Virginia — Stonewall Jackson’s sister-in-law — Janet Schaw, who wrote ecstatically but without exaggeration about the transcendant beauty of North Carolina — Augusta Jane Evans Wilson, whose novels outsold Uncle Tom, or Constance Fenimore Woolson — one of those Fenimores — none of these ladies gets the critical attention that she deserves. Or even the appreciation that she merits, just for the pleasure of hearing her voice.

Oblivion is one thing, but purposeful suppression naturally enters into it too. Works by such titans as John Taylor of Caroline, St. George Tucker and the whole constellar Tucker clan — James Madison, for that matter — the foundation stones of American Constitutional law, were heavy lifting even in their day. But now they’re just impossibly puzzling to post-bellum readers raised up in the Gettysburg Gospel, and so generally ignored by the professorial class.

But what a loss is Southern humor! The busy cities, the ample plantations with those unrivalled libraries, the dash and energy and practical acuity of the educated class, were hospitable ground for a humor as cheerful as the land itself. Just before the War that humor naturally acquired a tart tang of the acerbic, and after Appomattox it turned sardonic, sometimes, but it’s still funnier than anybody knows today. From the Jamestown landing until the end of Reconstruction Southern humor danced across the whole spectrum of types, from William Byrd’s polished Augustan wit to the rowdy dialect cackling of Bill Arp, the Confederacy’s unofficial court jester.

As always, you have to view anybody’s writing in its context of time and place, of prejudice and politics. But the suppression of the South’s rich treasury of writing strikes, really, at the identity of all Americans. Arp does need some considerable redaction — his comments on race are as unfunny as they are offensive — but on the other hand Harris gathered, sincerely and with love, the humor of slaves that would have been lost entirely if he hadn’t recorded it for us.

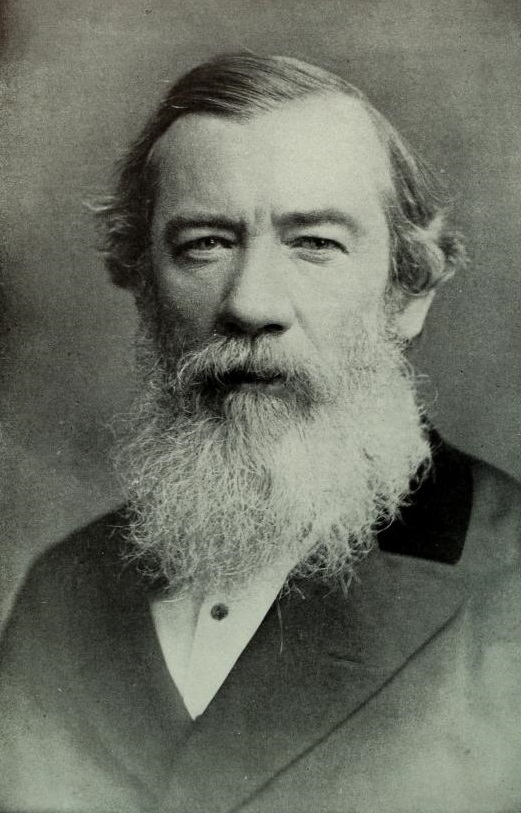

The twentieth century produced plenty of critical studies of Harris’s work and a good biography or two, all readily available today, and historians still use his letters as sources. But it’s nearly impossible to get a copy of his tales of Uncle Remus, now surgically excised from libraries and even online archival collections. As his books are practically the sole and only source of these African story-telling traditions and priceless notes of the Black dialect of the day, it’s heartbreaking to see the whole of his informants’ contributions to American literature now paradoxically cancelled on the ground of racism. Especially as there’s reason to suppose that Harris’s illegitimate father was very possibly Black himself.

In any event, even Americans who love Dixie seem to have forgotten the glitter and the brilliance, the grace and the strength, the charm and the delight of Southern literature of the two and a half centuries before the War. Open that bright vista, and see it for yourself. We don’t call it the Smiling South for nothing, you know.

Uncle Remus originals https://archive.org/search?query=uncle+remus