A review of The Rebel and the Rose: James A. Semple, Julia Gardiner Tyler, and the Lost Confederate Gold, by Wesley Millett and Gerald White, Cumberland House Publishing, August 24, 2007.

Millett and White have written a terrific “three-‘fer”: A wartime romance, a history of the flight from Richmond, and an economic reckoning of the Southern Treasury. They have succeeded, respectively, through narrative skill, meticulous scholarship, and mostly good accounting arithmetic.

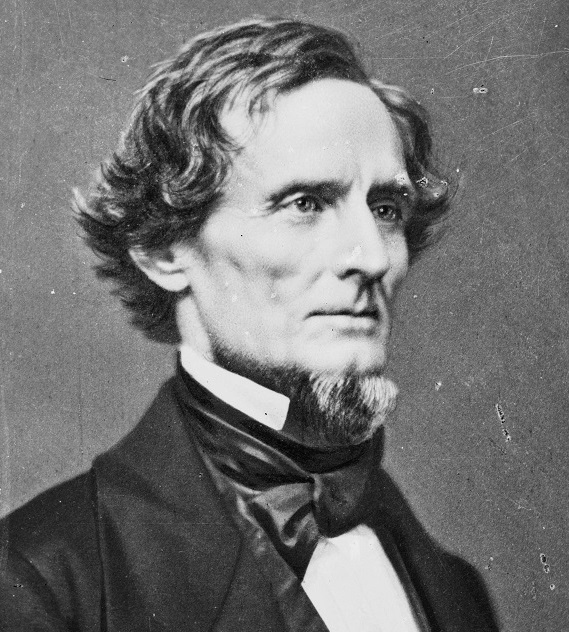

Their account might have been told without highlighting the role of James A. Semple and Julia Gardiner Tyler, but the two played important parts in the Confederate war effort, and not only in the events beginning on April 2, 1865, when General Lee finally convinced President Jefferson Davis to abandon the capital at Richmond, Virginia in the face of the Union advance.

James A. Semple was a distinguished captain in the Southern navy who had truly seen the world. His command of several ships had taken him to Tokyo, Europe, South America, and every part of the Mediterranean. He became a key provisioner for the navy, and in that role placed depots of food and clothing not only along the Southern coast, but also inland, including Danville, Virginia. His counterpart in the Confederate army was W.F. Howell, brother of Varina Davis, who deserves a book in his own right. Both were energetic and resourceful men who were indispensable in that unsung effort behind any fighting force: The unglamorous science of logistics.

Despite coming from a distinguished northern Virginia family, Semple lost his parents early and grew up in hardship. Nevertheless, in 1839 he married Letitia Tyler, a daughter of President John Tyler, who served as President from 1841-1845 when President William Henry Harrison died in April 1841 after a month in office. Tyler’s first wife (also named Letitia) died in 1842 after bearing eight children, and two years later he married Julia Gardiner, 30 years his junior, who would bear seven more of his children before Tyler’s death in 1862. The young Letitia bore a bitter dislike of the charismatic and beautiful Julia, and this resentment may have contributed to the early separation between Letitia and James. And possibly Letitia sensed that her husband was very much attracted to this widow, Julia Gardiner Tyler. The Rebel and the Rose quotes from several of Semple’s quite passionate love letters to Julia. In one of them, written possibly at the limit of daring for a Southern gentleman, Semple praises the buxom, “Raphaelesque” beauty of Julia. But they were never to marry.

The flight from Richmond began on Sunday, April 2, 1865, with a note received from General Lee by President Davis as he sat in his pew in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. It was not the first admonition by Lee to evacuate the capital, but it was the most urgent. Preparations began almost immediately to put the Confederate Treasury onto the train to Danville, some 120 miles to the southwest – one of the few escape routes, and mostly unmolested by the war. Under the direction of Secretary of the Treasury George A. Trenholm, Semple called up some young midshipmen to serve as guards for the funds that he and his co-worker, Edward M. Tidball, chief clerk of the Confederate navy, packed into wagons for transport to the train station.

Trenholm had replaced Christopher Memminger when the latter was forced to resign on July 1, 1864, after issuing Confederate bank notes devalued to one-third that of previous ones. But by the time the train finally left the station about midnight (delayed by the indecisive Davis), the peach brandy shared with other cabinet members in combination with morphine had made him very sick. When the train arrived in Danville in the afternoon of April 3, Acting Secretary of the Treasury became John H. Reagan, then Micajah H. Clark, who would finally transfer his duties to John C. Hendren. It would be Clark who would give the most detailed accounting of Treasury funds to a newspaper, where he attests to $327,022.90 in gold, silver, and gold and silver bullion, when a counting was done a month later, on May 4, 1865. There had been no time to do a more exact accounting during the evacuation, other than to mark values on the sides of the packed crates. Another account, without mentioning monies, was given in the diary of Tench Francis Tilghman (a member of the prominent Virginia family, whose ancestor was a trusted secretary to George Washington), who stated that what was left of the Treasury ended up in Florida.

Probably the most fungible asset on the train were 50 kegs of Spanish silver reales – the legendary “pieces of eight” of pirate treasure – each keg containing 4,000 coins, each valued at slightly less than a dollar, or almost $200,000. (All figures given here are historical values, not revalued for the present.) Two of these would be opened in Danville, one for expenses, the other to allow the citizens of the town to redeem their worthless Confederate dollars at the rate of 70 to one coin.

Davis and his entourage of cabinet members, functionaries, and guards did not stay long in Danville. Lee’s dwindling forces – many of them unpaid and hungry, who could see that the war was lost – could not prevent the advance of Grant’s armies. Davis’ plan of action was delusory: To somehow get to Texas and then continue the war with armies funded by what was, as we shall see, piddling funds from the Treasury. Nevertheless, following that plan, the group and the treasure headed south, after first sending 10 kegs of silver (slightly less than $40,000) to Greensboro, North Carolina under the care of John C. Hendren to pay Joe Johnston’s troops, who were fighting a delaying action against General Sherman, and leaving 38 kegs in Danville, presumably for General Lee to retrieve for payment of his troops [Millett and White, page 93]. Acting Treasury Secretary John C. Hendren placed two boxes of gold sovereigns, with a total value of $35,000 dollars, in Davis’ carriage [Millett and White, page 100].

Both the entourage and the Treasury funds were dissipated in the flight south. The rather complex accounting of the funds will follow. Here is a clarified statement of the entourage movements:

| Arrival date | Location |

| April 3 | Danville |

| April 10 | Greensboro, North Carolina [1] |

| April 14 | Charlotte, North Carolina |

| May 2 | Abbeville, South Carolina [2] |

| May 3 | Washington, Georgia [3] |

| May 6 | Sandersville, Georgia [4] |

| May 9 | Irwinville, Georgia [5] |

| May 15 | Panhandle of Florida [6] |

| May 22 | David Yulee Plantation, Florida |

Of the $35,000 sent south alongside but separate from President Davis’ entourage, $25,000 remained with Clark’s group. About a quarter of this remainder was entrusted to one of the 12 men for Varina Davis’ care. Members of the group received unspecified moneys, with M.H. Clark taking the unstated remainder to be placed “on deposit in London to be used as President Davis and Acting Secretary of the Treasury [other than himself?] might direct [Tilghman diary, page 170].” Supposedly “Confederate Jefferson Davis instructed [Raphael J. Moses, a Confederate Jew] to take US$40,000 in gold and silver bullions from the Confederate Treasury to feed and clothe the defeated Confederate soldiers.” Clearly all this money could not have come from Clark, even assuming that he succeeded in getting his mite to London, which would have been a feat. Where did it come from?

The accounting for all the Confederate Treasury funds is complex, and unfortunately Millett and White are not as clear as they could have been. The authors provide an appendix to detail this accounting, but it is a muddle: Debits and credits are mingled, instead of being clearly presented in a balance sheet [Millett and White, page 251]. In any case, briefly stated: The entire wealth of the Confederacy when the Treasury arrived in Danville, Virginia on April 3, 1865, was less than $600,000. Here is the total accounting, as I piece it together [Millett and White, page 254]:

| Amount | Accounting |

| $288,022.90 | Gold, silver, and gold and silver bullion. Clark’s May 4 count. |

| $39,000.00 | 10 kegs of silver reales sent Johnston’s troops in Greensboro. |

| $4,000.00 | Gold coins to repair roads ahead of southbound entourage. |

| $8,000.00 | 2 kegs of reales: For Danville redemption and expenses. |

| $339,023.90 | Subtotal of above 4 entries. |

| $35,000.00 | Gold sovereigns for Davis, not counted by Clark on May 4. |

| $152,000.00 | 38 kegs of reales for Lee’s troops (not $196K as given in book). |

| $526,023.90 | Likely total of bullion and coin (not $562,023.90 as in book). |

| ? | Liverpool acceptances (foreign exchange paper). |

| ? | Keg of copper pennies. |

| ? | Trunk of jewelry (solicited by Trenholm from Southern belles). |

So then, where’s the treasure? According to the authors, “the bulk of the specie was paid out” [Millett and White, page 246] – except for $86,000 [Millett and White, page 247]. Where did that go?

$27,000 went to Edward M. Tidball, chief clerk of the Confederate navy and Semple’s co-worker, who returned with it to his plantation in Winchester, Virginia – a plantation he immediately restored and expanded. $24,000 went to logistician W.F. Howell, brother of Varina Davis, who took it to Montreal, Canada and set up a business, much to the consternation of Semple. And finally, $35,000 went to the hero of our story, Captain James Allen Semple, who scattered it among friends throughout Georgia, especially around Savannah, with the intention of getting it to a bank in the Bahamas – which never happened. Instead, the Southern gentleman spent the money on the upkeep of his separated wife Letitia, and on the maintenance of Julia Gardiner Tyler and her family of seven children, including the financing of the education of her two oldest sons in Germany. He spent all of this and returned to his home in Virginia, where he died in 1882, age 63, penniless.

It is not certain what happened to the Liverpool acceptances owing for delivered cotton, other than they were entrusted to Postmaster John Reagan, who remained with Davis to the day of his capture on May 10. The keg of copper pennies and the trunk of jewelry, amassed by Trenholm by appealing to Southern ladies after the Confederate Congress refused his demands for taxes, are unaccounted for.

And there you are, shovel packed, looking mighty glum, aren’t you? But Millett and White offer a glimmer of free treasure on the last page of their book: What happened to that $152,000 – the 38 kegs of silver reales left behind for Lee in Danville? That is the only part of the treasure unaccounted for. Wow, out the door with your shovel, are you?

But wait, now, come back here! There are just two things to give you pause: The city of Danville has so far prohibited any digging in the depots set up there by Semple – the most likely site of any buried treasure – and not just because part of those depots are now a cemetery [Millett and White, page 247]. And, as stated by author Robert C. Jones (below), on March 23, 1867, Congress passed a law stating that all Confederate Treasury money is the property of the U.S. government.

Maybe you’d like to ease back into that recliner and tune in another episode of Gold Rush, right?

Millett and White have written what I think is the last word on Confederate gold – a scholarly, well-documented history with a great love story and a treasure hunt. But if you would like to check their work, here’s a brief bibliography of others who have treated – and mistreated – the subject:

- 2019, Lost and Buried Treasures of the Civil War, W.C. Jameson; ISBN 978-1493040759; 168 pages.

Jameson, a professional treasure hunter, provides novelized accounts of 31 treasure troves, most of them with more made-up dialog than actionable detail. This vagueness belies his own point that the era is rich in documentation compared to folkloric or mythical accounts of buried treasure. - 2016, Knight’s Gold, Jack Myers; ISBN 978-1539896562; 510 pages.

Myers retells the story of a cache of gold coins discovered by two boys in a Baltimore tenement building in 1934 – presuming to correct the 2008 account by Leonard Augsburger, Treasure in the Cellar. According to Myers, the trove was put there by five members of the Knights of the Golden Circle. He, like most authors who treat this subject, connect the KGC with President Davis’ fatuous desire to restore the Confederacy somewhere outside the South. Alas for would-be treasure hunters, this gold was distributed by the courts to various claimants in the 1930s. - 2015, Lost Confederate Gold, Robert C. Jones; ISBN 978-1514275221; 162 pages.

Jones, a prolific author of over two dozen mostly historical books, touches on many of the particulars offered by Millett and White of the flight from Richmond, beginning the night of April 2, 1865. He further details the fate of about $450,000 in specie from Richmond banks, separate from that of the Confederate Treasury, much of which was returned to those banks. For example, he tells of the May 24, 1865, raid on a Richmond bank’s gold near Danburg, Georgia, in which Confederate veterans took about $140,000 of the $250,000 total. To the disappointment to gold diggers, he points out that any discovery would be a waste of time: On March 23, 1867, Congress passed a law stating that all Confederate Treasury money is the property of the U.S. government. - 2015, Lincoln, Sherman, Davis and the Lost Confederate Gold, Patricia G. McNeely; ISBN 978-1517212384; 294 pages.

McNeely’s book is a seedbed of conspiracies, asking whether General Sherman accepted a bribe of $13 million in Confederate gold, and whether a man who died in 1893 in Enid, Oklahoma was in fact John Wilkes Booth. Of course, $13 million is a wildly impossible overstatement of the Confederate Treasury, but even her estimate of $950,000 is too high. McNeely was a professor of journalism at the University of South Carolina for 33 years. - 2005, Rebel Gold: One Man’s Quest to Crack the Code Behind the Secret Treasure of the Confederacy, Warren Getler and Bob Brewer; ASIN B000SEQDW2; File size 32,435 KB. This seems to be the Kindle version of the book below.

- 2003, Shadow of the Sentinel: One Man’s Quest to Find the Hidden Treasure of the Confederacy, Warren Getler and Bob Brewer; ISBN 978-0743219686; 320 pages.

Brewer, with writing assistance from Getler, tells not specifically of the Confederate Treasury, but of the Knights of the Golden Circle, who wished to restore a future Confederacy, the attempt to be funded by many treasure troves scattered throughout the South, each protected by a trusted KGC sentinel. Many officers of the KGC were Masons, and they used encrypted symbols to map these locations. According to Brewer, a “Bible Tree” near Hatfield, Arkansas was carved with these symbols, and he decoded some of them, locating several KGC caches and recovering “gold coins, guns, and other treasure”. He further asserts that Jesse James was a Confederate guerrilla whose stage and bank robberies helped to fill KGC treasure chests.

The gold was the stories our ancestors passed down about old men and boys fighting professional soldiers at the Battle of Marianna. We shot a communist General Asboth in the face and arm and he eventually died of his wounds. Asboth had been run out of Europe during the 1848 Communist Revolution and found a home in Abe’s army, since Abe was willing to take any psychopath into a blue uniform if he’d kill innocent people, burn homes and cities and then pretend he did it not from enjoyment but to “free slaves” despite not ending slavery in the United States prior to the invasion of the Confederacy.