The Scottish secession vote has led to a great number of pieces about the future of secession and its viability in the United States:

1. Ryan McMaken wrote about it at Mises Daily.

2. Business Insider featured a nice map on several secessionist movements in Europe.

5. The Associated Press did a story on Catalan independence.

6. A Daily Caller Op-Ed by Douglas MacKinnon discussed his new book, The Secessionist States of America: The Blueprint for Creating a Traditional Values Country . . . Now, which cites my article on the legality of secession at The American Conservative.

7. And of course the two articles that appeared at the Abbeville Blog on Scottish secession by Don Livingston and Dan E. Philips.

There were thousands of posts about secession across the Internet, but when the mainstream media begins to discuss an idea, it is beginning to have some currency among the general population.

Yet, all of these articles either directly or indirectly point to the two persistent obstacles to American secession, at least according to opponents, namely the Constitution and the interpretation of the War for Southern Independence. Is secession Constitutional and can it be legally done, or is it an act of revolution? And, can American proponents of smaller states and self-determination overcome the modern dogma surrounding the causes of the War?

The first question can be addressed succinctly. The method used to frame the Constitution is the model modern secessionists should use when advancing independence. The United States already existed in 1787 when 55 delegates from twelve States met in Philadelphia to discuss potential changes to the Articles of Confederation. These men were sent by their State legislatures and formed a convention, a purely American idea, to propose and concur on solutions to pressing issues, namely commerce and defense. They spoke not for themselves, but for the people of their State, and were beholden to the instructions from their respective States in regard to any action that might be taken by the group.

On June 19, 1787, James Madison insisted in Philadelphia that once one party had breached a compact—both the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution are compacts between States—the other parties were no longer obligated to the instrument. Madison said:

It had been alleged, (by Mr. Patterson,) that the Confederation, having been formed by unanimous consent, could be dissolved by unanimous consent only. Does this doctrine result from the nature of compacts? Does it arise from any particular stipulation in the Articles of Confederation? If we consider the Federal Union as analagous to the fundamental compact by which individuals compose one society, and which must, in its theoretic origin at least, have been the unanimous act of the component members, it cannot be said that no dissolution of the compact can be effected without unanimous consent. A breach of the fundamental principles of the compact, by a part of the society, would certainly absolve the other part from their obligations to it. If the breach of any article, by any of the parties, does not set the others at liberty, it is because the contrary is implied in the compact itself, and particularly by that law of it which gives an indefinite authority to the majority to bind the whole, in all cases. This latter circumstance shows, that we are not to consider the Federal Union as analogous to the social compact of individuals: for, if it were so, a majority would have a right to bind the rest, and even to form a new constitution for the whole; which the gentleman from New Jersey would be among the last to admit. If we consider the Federal Union as analogous, not to the social compacts among individual men, but to the conventions among individual states, what is the doctrine resulting from these conventions? Clearly, according to the expositors of the law of nations, that a breach of any one article, by any one party, leaves all the other parties at liberty to consider the whole convention as dissolved, unless they choose rather to compel the delinquent party to repair the breach.

Article 13 of the Articles of Confederation mandated that any changes to the document had to be “agreed to in a Congress of the United States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every State.” This was ignored by the delegates to the Philadelphia Convention because the people of the States could decide to “alter or abolish” the general government without the consent of either Congress or the State legislatures. A convention was and is the voice of the people of the State and legislative powers are “incapable of annihilation.” Thomas Jefferson articulated this position in the Declaration of Independence. While the Constitution established a “more perfect Union,” the same Union of States as under the Articles of Confederation, the document was framed in a method consistent with the American principle of self-determination, namely in convention, and ratified by the people of the States in popularly elected conventions. That is where the document found its meaning. Government cannot dictate to the people when or how to exercise their “right” or “duty” to change their system or structure of government.

The Constitution was framed and ratified in direct violation of Article 13 of the Articles of Confederation, and the founding generation considered it legal. If a State legislature were to call a convention of the people of that State and that convention voted for independence based on an explicit list of violations to the federal compact, that State would be following the procedures established by the founding generation from 1776-1788.

Article V of the United States Constitution provides for a convention process to amend the Constitution, but each State, in convention assembled, could then choose to leave the Union and form a new government, either in Union with other States or as independent republics as the twelve States who met in Philadelphia chose to do in 1787, or to amend the existing Constitution and remain in the United States of America. No State could legally compel the others to remain bonded to the United States. Madison said as much in 1787. That would be an illegal use of force. See Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln exemplifies the second argument against secession, i.e. the issue has already been settled by the War. This position will be more difficult to overcome, particularly with the entrenched modern education system. The arguments for secession are nuanced and intellectual. Lincoln’s response was brute force, something any person can understand, and propaganda later seized upon as fact by the historical establishment. The myth of self-righteous Yankees involved in a war for humanity against evil Southern slave-holding devils has been crumbling in recent years, but it is far from dead. The fact that even a quarter of Americans now recognize that independence may be a valid option to rid themselves from oppressive and illegal acts by the general government speaks volumes about American education. We have come a long way but still have a long way to go. But there is hope. Young people are leading the charge for independence bolstered by the volumes of information available on the Internet about independence, secession, and self-determination and the holes in the modern narrative about the War. Poor historical interpretation is, thankfully, not indefinite.

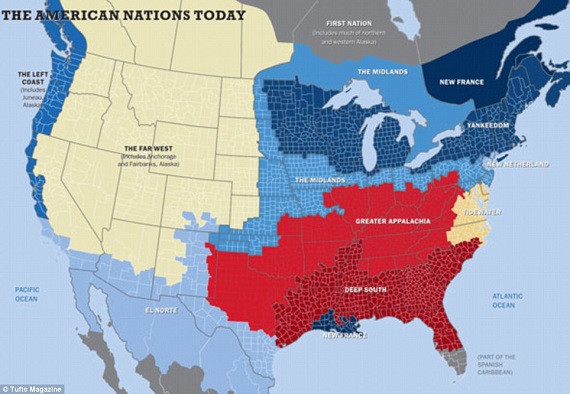

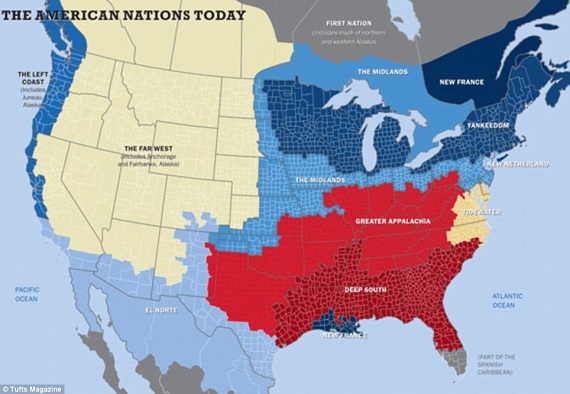

This political revival must be grounded in something tangible—culture. The “multi-culturists” have done a fantastic job explaining that America is not a unitary State made up of an American nation, a single people. A Utopia for utopians does not exist and never has on American shores or elsewhere. Southerners have been saying that since before the Constitution was ratified, though from the earliest travelers to the present they have always recognized Heaven is probably a lot like Dixie. Peaceful secession is the recognition that people can choose to live their own lives with people of like culture in harmony with others. After all, “Good fences make good neighbors.” It seems much of the world is starting to understand what Americans have always known. We just need to reconnect with our Jeffersonian past.

Hello Brion,

Love this article, especially for the new insight into the Articles of Confederation vs. the Constitution. I have just finished a book on the AOC, something I’ve never studied in depth before. I was a History major in college but had to discontinue my education due to an onset of mental illness. It sounds like our government was founded on deception and lies, something that permeates within our current government. Even as a kid in high school, completely unaware of my lineage, I felt a “pull” towards the South(Confederacy.) After college, I did my own studying and research on my family history and I actually have a direct connection to 2 family members who fought for the South. I was indeed honored to be eligible to be a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. I didn’t go through the process at that time because I wasn’t in the best mental state. I will have to revisit that very soon.

Thanks for the new information, kind sir!