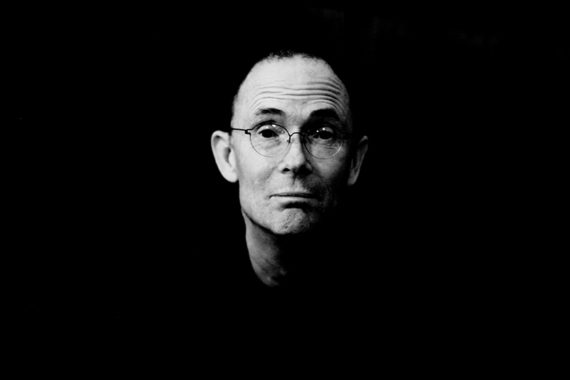

William Gibson surprises people when they meet him. The writer who coined the terms “cyberspace” and “megacorp,” whose dystopian novels re-invented science fiction in the 80s, and was lauded in The Guardian (UK) as “the most important novelist of the past two decades,” greets people with a slow, easygoing Southern drawl – not the voice one would expect from a writer associated with cyberpunk.

He got that accent honestly. Born in 1948 in Conway, South Carolina, and raised in his parents’ home town of Wytheville, Virginia, young William was an erratic student and loner. His father’s job required the family to move often, which probably did not help Gibson make friends or concentrate in school. At Pines Elementary in Norfolk, he preferred to read works of his own choosing instead of his assignments. When his father died on a business trip, William and his mother returned to Wytheville in the Appalachians. Although he had determined to be a science fiction writer at age 12, he remained an unmotivated student through high school. His mother died when he was only 18.

He dropped out of college and flitted from job to job, earning an uneasy living as an antiques dealer, managing a head shop, and as a teaching assistant. After marriage and a child, Gibson began writing seriously. The short stories he published in the magazines Omni and Universe 11 saw the first appearance ofthe raw, gritty fiction critics have since dubbed cyberpunk, a sub-genre of science fiction that focuses on a near future of “low life and high tech.”

The themes William Gibson explored in those short stories and his subsequent novels echo themes found in Southern thought and literature.

For starters, Gibson’s troubled youth taught him about the precariousness of life, and imbued him with a deep distrust of triumphalism and progress. In one of his early stories, “The Gernsback Continuum,” Gibson savagely (and humorously) ridiculed utopian science fiction and confidence in boundless progress, practically an article of faith animating most of the science fiction at that time.

The fusion of corporate and governmental power has long troubled Gibson. In his Neuromancer trilogy, he used the term megacorp to describe a business conglomerate that not only wields vast monopolistic power over powerless consumers, but also controls the government. This calls to mind the warning from the Introduction to I’ll Take My Stand:

“… the true Sovietists or Communists—if the term may be used here in the European sense—are the Industrialists themselves. They would have the government set up an economic super-organization, which in turn would become the government.” (p. 41)

Gibson sees the merger of big business and government as an anti-human force that can drown out not just individuality, but all local culture. In his novel Pattern Recognition, Gibson’s protagonist, Cayce Pollard, is a “cool hunter,” a specialist who discovers and documents current ideas and designs in order to supercharge advertising campaigns. The world Cayce inhabits is completely globalized into a rigid “monoculture” that reacts to sales hype the same way all over the world. The products she sells do not benefit consumers, and are in fact the same things that are constantly re-packaged to take advantage of the latest “cool” trends.

This echoes another quote from I’ll Take My Stand:

“… the rise of modern advertising—along with its twin, personal salesmanship—is the most significant development of our industrialism. Advertising means to persuade the consumers to want exactly what the applied sciences are able to furnish them. It consults the happiness of the consumer no more than it consulted the happiness of the laborer. It is the great effort of a false economy of life to approve itself.” (p. 44)

But even with such forces warring against human nature, many of Gibson’s characters stubbornly rebel despite the odds. As the Guardian article observed, Gibson “is basically a conservative author; he doesn’t really want to engage with the possibilities of the post-human.” One such character, Henry Case of Neuromancer, is a “console cowboy,” a once-gifted data rustler who’s been poisoned by a vengeful ex-employer, which has robbed him of his abilities as a hacker. In a novel that’s equally science fiction and noir, Case struggles against the megacorps in a one-sided conflict.

Ultimately, he fails. At the end of the novel, his enemies still control him. However, Case manages a partial victory by reclaiming many of his old abilities. So even when the cause is lost, the act of resisting restores at least a sliver of one’s humanity and dignity.