Just as the Earth revolves on its axis each day and travels around the Sun in an equally regular pattern, so has world history tended to be cyclical in nature throughout the centuries, with many episodes seemingly being repeated countless times over. In many cases the basic cause behind such recurring cataclysmic events as war, radical changes in political systems or the fall of nations and empires has involved economics. A current example of the latter is the financial dilemma which now threatens to bring about the economic, if not the total, collapse of the European Union . . . namely where to find the more than eighty billion dollars in revenue that will be lost due to the United Kingdom’s secession from the Union. A similar economic situation had faced Great Britain itself almost two and a half centuries earlier on the other side of the Atlantic. At that time, thirteen of its major colonies, with a cry of “no taxation without representation,” declared their independence, seceded from the British Empire and joined together to form the United States of America. Faced with the loss of a vast source of the revenue needed to fill coffers drained by its seemingly endless wars with France, Great Britain opted to wage war on its own colonies.

Less than a century later, seven of the States in the new American nation felt that the weight of long economic oppression by the Federal government was more than they should be forced to bear and opted to secede from the Unites States to form their own more perfect union . . . and once again the action brought forth a war in which the central government attacked its own citizens to prevent their departure. Today, the majority of historians cite only slavery as the central cause of the War Between the States, and while the institution did play an important role in events leading to the South’s secession, it certainly was not the casus belli itself. During the antebellum period there were groups of Americans in both the North and South which were opposed to the concept of human bondage and actively worked to abolish slavery, but with only a very small minority of them advocating total integration following emancipation. However, the majority of Americans, including leaders such as Abraham Lincoln, were willing to allow the status quo to continue in regard to Southern slavery and many of them, like Lincoln, also felt that should the time ever come when the slaves were granted their freedom, they should be shipped out of their home country to some foreign land in Africa or the Caribbean.

Speaking of Lincoln, in his earlier statements he was quite definite in his thoughts about secession, slavery and black Americans. In 1848, when Lincoln was a U. S. congressman from Illinois, he gave a speech in the House of Representatives in which he stated “any people, anywhere, being inclined and having the power, have the right to rise up and shake off the existing government, and form a new one that suits them better. This is a most valuable, a most sacred right, a right which we hope and believe is to liberate the world.” In a letter a decade later, Lincoln wrote that “neither the General Government, nor any other power outside of the slave States, can constitutionally or rightfully interfere with slaves or slavery where it already exists.” The same year, in an Illinois debate with Senator Stephen Douglass, Lincoln said that he did not understand the Declaration of Independence “to mean that all men were created equal in all respects,” and added that he was not in favor of “making voters or jurors of Negros nor of qualifying them to hold office nor to intermarry with white people.” He then went on to say that “there is a physical difference between the white and black races, which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.” So much for the image of the “Great Emancipator.”

The antebellum controversy in regard to slavery was actually far more a matter of economics rather than one of empathy in that it primarily involved the extension of slavery into the existing American territories and newly created states. The North feared that slave labor would compete unfairly with its own low-wage, largely immigrant labor force which, unlike slaves, could be willfully hired and fired as needed and did not require food, housing, clothing or even rudimentary medical attention. This subject was discussed in depth by economists Robert Vogel and Stanley Enggerman in their 1974 book “Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery” and was earlier explored on an even more personal basis in interviews with more than two thousand former slaves in the “Slave Narratives” that were conducted from 1936 to 1938 by the Roosevelt administration. Contrary to what might be thought today, those interviews indicated that Southern slaves did indeed have better food, housing and medical care than most of the “free” workers in the North. The interviews also tended to expose as little more than myths the supposed horrors portrayed in contemporary works such as “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” as well as later writings and films, by pointing out that the physical abuse of slaves was actually uncommon in the South, and in many cases illegal. The “Narratives” further showed that over eighty per cent of the former slaves interviewed even had a favorable opinion of their former masters.

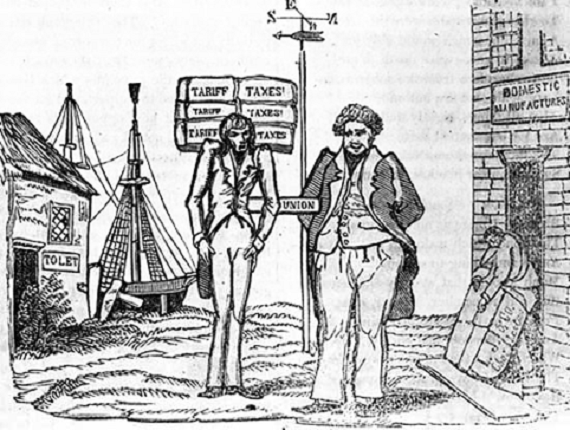

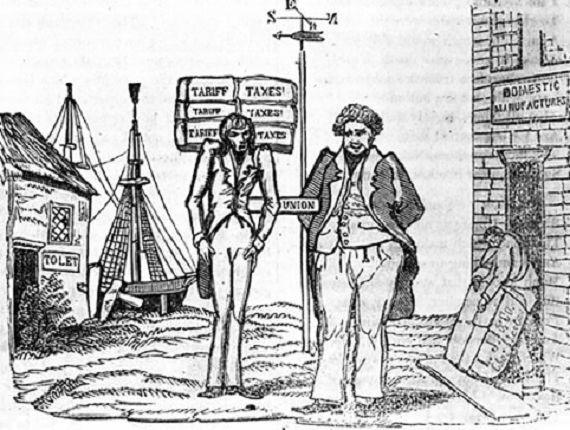

In regard to the true economic cause behind the War, just as it was with Great Britain’s case in 1776, the gaping hole that would be formed in the Federal revenue served as the actual rationale for the Union to wage war on the departed Southern States. In 1860, there were more than thirty-one million people in the thirty-three States and ten Territories, with only a third of these, including almost four million slaves, living in the South. According to the U. S. Federal Abstract for 1860, the total Federal expenditures for that year amounted to some sixty-three million dollars, with over eighteen million of this being used mainly to finance railways, canals and other civil projects in the North. On the other hand, Federal revenues at that time amounted to a little over fifty-six million dollars. As there was then no corporate or personal income tax and revenue from domestic sources, such as the sale of public land, amounted to less than three million dollars, the remaining fifty-three million dollars were provided by what was termed “ad valorem taxes,” in other words, the tariff on foreign goods imported by the United States. The basic problem with this, however, was that as much as three-quarters of that revenue was collected in Southern ports, which meant that there would be a loss of up to forty million dollars in Federal revenue if the Southern States left the Union. Added to this was the fact that well over half of America’s four hundred million dollars in exports in 1860 were agricultural products from the South, mainly cotton, rice and tobacco.

Even in his first inaugural address on March 4, 1861, only a month prior to the start of the War and the North’s invasion of the South, Lincoln stated that he would “hold, occupy, and possess the property, and places belonging to the (Federal) government, and collect the duties and imposts . . . but beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion, no using force against, or among the people anywhere.” Again, in regard to slavery, during the same address Lincoln basically reiterated his 1858 statement on the subject by stating he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” A month later, as matters were worsening in seceded South Carolina, Virginia, which still remained in the Union, commissioned a three-man delegation headed by John Baldwin, a pro-Unionist and former judge of the State Supreme Court of Appeals, to meet with Lincoln at the White House in an effort to negotiate a peaceful settlement. During their meeting, the president was reported as saying privately to Baldwin “but what am I to do in the meantime with those men at Montgomery (i.e., the Confederates)? Am I to let them go on and open Charleston, etc., as ports of entry with their ten-percent tariff? What, then, would become of my tariff if I do that, what would become of my revenue? I might as well shut up housekeeping at once.” Such sentiments clearly demonstrate that it was primarily the loss of Federal revenue, not the issue of slavery or the constitutionality of secession that formed the motivation behind Lincoln’s call to the Union for seventy-five thousand volunteers to suppress what he termed the “rebellion” of the Southern States. Lincoln’s call not only led to the secession of Virginia, but Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee as well, and brought about a war that made casualties of five percent of America’s population, devastated a third of the nation’s States and left deep wounds in the American psyche that to this day have not yet completely healed.

A comparison between the conflicts of 1776 and 1861 was also made in a “London Times” article of November 7, 1861, in which it was said of the War Between the States that the “contest is really for empire on the side of the North, and for independence on that of the South, and in this respect we recognize an exact analogy between the North and the Government of George III, and the South and the Thirteen Revolted Provinces.” Another English observer who had traveled widely in America prior to the War, author Charles Dickens, made a comment which bore even more directly on the economic cause of the conflict. In a letter written in March of 1862, Dickens stated “I take the facts of the American quarrel to stand thus; slavery has in reality nothing on earth to do with it . . . but the North having gradually got to itself the making of the laws and the settlement of the tariffs, and having taxed the South most abominably for its own advantage, began to see, as the country grew, that unless it advocated the laying down of a geographical line beyond which slavery should not extend, the South would necessarily recover it’s old political power, and be able to help itself a little in the adjustment of the commercial affairs.” In another letter the same year, Dickens wrote even more succinctly that “the Northern onslaught upon slavery is no more than a piece of specious humbug designed to conceal its desire for economic control of the Southern States.”

Dickens also had some extremely trenchant remarks to make concerning the South’s departure from the Union and the North’s feelings in regard to black Americans. On the former he stated “as to Secession being Rebellion, it is distinctly provable by State papers that Washington considered it no such thing . . . that Massachusetts, now loudest against it, has itself asserted its right to secede, again and again . . . and never hinted it would be Rebellion.” On the second matter pertaining to racial discrimination, Dickens said “Every reasonable creature may know, if willing, that the North hates the Negro, and until it was convenient to make a pretense that sympathy with him was the cause of the War, it hated the Abolitionists and derided them up hill and down dale.” Would that facts and statements such as these could somehow manage to find their way into the politically correct American history lessons now being presented to the nation’s students, as well becoming even a small part of the media’s biased coverage of current controversies and events involving the South.