From the 2004 Abbeville Institute Summer School.

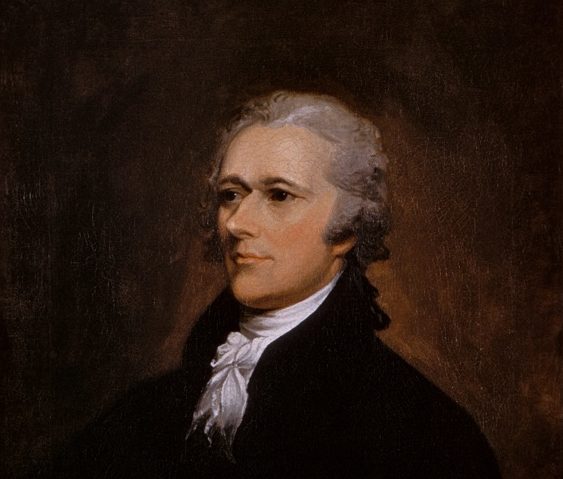

Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson have dinner. It looks like funding an assumption of State debts by the general government is not going to go through, and Hamilton’s very worried because U.S. stock is plummeting in the international finance markets. So, a deal is struck. Jefferson will put pressure on his people to remove their objections to funding an assumption if the capital is moved to Washington. All of us who know Washington today would probably think that’s a terrible deal, but it probably wasn’t that bad a deal. Washington would remain a Southern city in many respects well until after World War II. It’s not going to be until the expansion of L.B.J.’s Great Society that it becomes something different. Southerners would set the social tone and would have an easier time getting their folks there for quorum votes. From the Jeffersonian mindset, something made sense about getting this thing out of Philadelphia where the Bank of the United States was located or out of New York where the financial situation was located and sticking it in a swamp on the Potomac River. That was not necessarily a bad place to have a capital, because hopefully you could insulate it from these terrible influences in Philadelphia and New York. The evidence for this deal is circumstantial, but they both admit to having dinner. Jefferson would later claim that is not exactly what happened, but he never gives a good account of what exactly did happen. My point would be though, given the context of the times, I don’t think it was that bad of a deal though I would have opposed it myself. This funding of assumption was very dangerous and was very closely tied to the Bank. But at the time the view was that it was important where your capital was going to be located, especially for future times. Jefferson also had a deep, abiding faith in the people. The people were going to see what was going on and vote these folks out eventually. And he was right, as we are going to see when we get to his first term.

The subsidy issue and the tariff issue were also kind of interesting and it’s actually going to cost Hamilton as we go forward. Hamilton is beginning to win some success with his program. He really is in the driver’s seat. He begins to have folks introduce bills for the subsidization of manufactories and fisheries and things of this nature. These are hard bills to get through the Congress. They’re very difficult because nobody is yet logrolling effectively enough. You’re not subsidizing enough things to get enough people to jump on the log and get the thing rolling down the hill, right? And he’s introducing this legislation piecemeal and it doesn’t tend to go anywhere. He does get a tariff passed. But there’s a couple things that begin to happen that fracture his coalition which was very crucial to his program. One of those things was that the manufactories of Pennsylvania wanted tariffs, not direct subsidies. They were hoping for tariffs from the very beginning when the tariff debates started and James Madison was like, “How about five percent? That’s what we’ve always agreed to.” You’ve got the delegates from Pennsylvania saying, “No, we want twenty percent. We want protection. Listen we fought the Revolution too. Our guys did just as good a job as anyone else in this war. We should be able to get the same kinds of benefits we enjoyed under the British empire, so we want twenty for absolute protection.” Madison says, “How about six?” “No, twenty.” “How about seven?” “No, twenty.” Hamilton wouldn’t go twenty either. Hamilton kept his tariffs predominately revenue and mildly protective for most of the time that he was Secretary of the Treasury and he begins to alienate some very important folks in Pennsylvania. The most important of these was Tench Coxe. Tench Coxe had worked with Hamilton (he had a few personal beefs with Hamilton, but nothing big), but he also began to work with Jefferson on some interesting side issues about fisheries management in New England and other things of that nature, and the two develop a relationship. It’s through Coxe that Jefferson and others find out that there is some dissatisfaction with Hamilton.

The other thing that Hamilton does because things are not going well is beginning to pass internal taxes. The whole idea behind tariffs as a revenue was to avoid internal excises and he begins to pass them, the most famous being the one on whiskey. The whiskey tax also had a moral element to it. It went along these lines: the folks that supported the whiskey tax had the view that, “You know what? Those Scots, Irish, and Germans in the backcountry drink too much, and whiskey is spiritist.” Meanwhile, none of these excises were passed on Madeira or Port, which is drunk in large quantities up and down the eastern seaboard. “That’s okay. We can handle it, but you’ve got to watch out for those Irish, Scots, and Germans and that whiskey.” And even in Hamilton’s correspondence, this comes out very clearly. He’s hoping that by taxing it, he can lower the consumption of these goods. Probably the only thing it was going to do was make them consume more because it no longer paid to ship it across the mountains or the rivers at the time.

In any event, a lot of the manufactories are also very upset with the internal taxes because internal taxes are crimping their ability to accumulate capital. But there’s a third thing. Capital is timid. This is one of the rules if you ever go into investing. It’s very difficult to get people with a lot of capital to invest in certain things. Ask folks who run institutes or schools for instance, they’re very tight-fisted with that capital. And when a lot of these folks who were beginning manufacturing establishments go to the branches of the Bank of the United States or the Bank of the United States in Philadelphia, they’re getting shut out of credit facilities. The Bank of the United States was tending to put most of its loans in commerce and in shipping. That seemed to be where the safe area was and where the safe return was. They were not putting much in manufacturing. Tench Coxe would take this up with Hamilton and others and say “We have to change this. A little subsidy is not going to help us if I can’t get the loan to start up forging a situation to begin with.” It wasn’t changing and this would continue to fester, especially in Pennsylvania.

There are two things that are hitting the manufactory folks, particularly in Pennsylvania. One is the excise taxes they’re having to pay. So that’s eating into some of their capital for investment. The second thing is they’re getting shut out of credit facilities and the Bank of the United States is being stingy with the loans that they’re making. Now in the Bank’s defense, manufacturing is risky, extraordinarily risky to put your money into. You sink a lot of money into cost quickly. You’ve got a lot of overhead. If some bumpkin comes out of the Pennsylvania woods and says, “I want to start textiles,” you go, “Yeah, right. We’re going to give it to Hancock because he proved he can ship in good times and in bad, legally and illegally. That man will turn a profit.” So, this will fester with these Pennsylvanians over time and it’s a fairly important thing to bear in mind.

Ultimately, how does the Jeffersonian opposition deal with this? First, let’s take a look at Madison as he emerges as the floor leader of the House. Madison doesn’t do very well with funding the assumption because he wants to play the middle, so he doesn’t want to go to the extreme of, “This is immoral. This is dangerous. We know what you’re up to.” He doesn’t want to support funding an assumption. Which really hurt Hamilton’s feelings in lots of ways because Hamilton had thought that he had an understanding with Madison. Madison comes up with the most complicated formula for funding an assumption that a man could possibly devise. He was going to discriminate between the original holders of the debt, whoever they may have been (they may have signed their bonds or may not have signed their bonds) and later holders of the debt. But sometimes this debt went through four, five, or six hands before it landed in somebody’s office up in New York. It was unworkable. In fact, one Pennsylvanian, William McCauley, said, “This man is going to ruin the opposition with his obstinacy.” Even when his own people, Jeffersonians from Pennsylvania, Virginia, etc. talked to Madison and said, “You’ve got to come up with a different tactic,” but he refused. So, funding an assumption was stopped in spite of Madison and then proceeded to go forward based on a different political deal at the time. When it came to the chartering of the Bank of the United States, Madison also proved to be ineffective there, almost laughably so.

One of the things going for Hamilton was winning that first battle of funding the assumption. Presidents often find that if you win that first major legislative battle, the rest of your program can proceed apace. This proved true for Hamilton as well. Madison argued stringently against the Bank, on economic grounds, moral grounds, but one of the arguments he made was, “We said no at the Constitutional Convention.” Madison’s recollection of the Convention was that charters were unconstitutional. They were voted down. Elbridge Gerry of Connecticut said, “That’s not the way I remember it.” Well, curiously enough, Hamilton never pulled out his notes and said, “Here’s the vote and here’s what we talked about” (probably because Madison was telling the truth). In fact, Fisher Ames would later write, “We don’t even have to ridicule Madison. His own party is laughing at him.” It suddenly didn’t matter. The Constitutional arguments didn’t matter. Hamilton had something that you might call political impetus, political motion. He was inertia, except in this case he wasn’t at rest. He was in motion and he was going to remain in motion until something comes up to stop him. Well, what stopped him?

One of the things that begins to stop the Hamiltonian program was a fellow from Switzerland, Albert Gallatin, who lived in Pennsylvania. Gallatin came from a financial background, a financial family in Switzerland, and was a wizard with accounts. He began to ask embarrassing questions like, “Where’s the account books? Are you guys giving us an accurate, detailed account of the United States and their expenses?” (Much of this happens after Hamilton is gone, by the way). Gallatin points out the rather embarrassing fact that, “On a per annum basis you all have been underestimating the debt by $400,000.” But the fellow who begins to really develop the counter-argument to Hamilton is, of course, John Taylor of Caroline. Taylor is extraordinarily difficult to read. John Randolph of Roanoke once critiqued one of Taylor’s works thus: “For heaven’s sake, get some worthy person (if you decline the task yourself) to do the second edition into English.”[1] Taylor’s writing is dense; there’s a great deal to unpack. He’s also archaic in his language. If you ever read him, please have an Oxford English dictionary on hand because he uses archaic terms and then he’ll use four or five descriptors for the same thing, he’ll call one debt instrument by four or five different names within the same work, so he can be a difficult read. Nevertheless, Taylor has a good idea of what’s going on. He writes a number of pamphlets, but the pamphlet that probably lays out his early thought the best and is a good introduction to him and his later works is called An Enquiry into the Tendency of Certain Public Measures, and it was an attack on what he called “the paper system.” And it was an argument for why the paper system in this political and economic consolidation (and Taylor begins to use the term consolidation), was so dangerous. Taylor makes the argument that this paper system ends up creating an “aristocracy of paper.” In other words, the holders of government debt and bonds and stock in the Bank, who are going to be paid their dividends on the basis of taxation. So, when the Bank of the United States would finance government debt and hold government bonds, it would become the receiver, not of folks who were investing directly in the Bank, but of folks who were being taxed to pay off those bonds, filling up the coffers of the debt. Essentially what all this amounted to was a tax, and a tax that fell especially hard on the landed interest, which was the dominant majority interest of the country at time. Therefore, this thing was corrupting. It created a class of stockholders utterly dependent upon the government who were benefiting off of the productive labour and wealth of the larger majority interest in the country. One of the things about Taylor and his writings is that while he’s been ridiculed by some historians and terribly misunderstood by others, his contemporaries had a high opinion of him. He would write a pamphlet or a book, and the other side would say, “We’ve got to get somebody to answer this guy.” In other words, Taylor’s contemporary opponents respected him and his arguments.

Taylor and Gallatin are the ones who begin to help crystallize the Jeffersonian program. They begin to take some of those things that were in the origins, the dangers about debt, the dangers concerned with consolidation, the obvious relationship to the Bank of England that all this seemed to have, and worked that into a program for America saying, “This is why what Hamilton has done and erected is dangerous.” And then Gallatin comes in saying, “Yeah and it doesn’t work either.” So it fulfills both, the pragmatic, but also the cultural and intellectual requirements necessary to make the argument persuasive during that day and time. So how does Jefferson get to be President? Is it just going to be on the basis of Taylor and Gallatin’s arguments? If politics were only that way, right? You get a bunch of people together, “We all agree.” It won’t work that way. Because we have interests, and we would have to figure out the weights and the balances. Jefferson needs Pennsylvania and he needs New York. Not a lot has changed. You still need New York oftentimes to carry a Presidential election. You did then. But he’s in good shape. There’s a number of things that have happened politically – the Alien and Sedition acts have been passed. That’s made quite a few people upset. The Hamiltonian economic program has done its damage as well, and what Jefferson is going to find in his election, close though it may be, is that he’s going to win enough votes in New York and Pennsylvania and in the South to forge a very strong coalition that’s going to carry him into the office. But our boys from Pennsylvania and New York, while they are going to agree with a number of aspects of the Jeffersonian program like, “Let’s get these taxes lowered, perpetual debt is not a perpetual blessing, westward expansion, we’re for that too,” there’s other things that they’re going to want that are going to be harder to get rid of. And Albert Gallatin himself is going to be difficult in certain respects.

Before we get to the sadder stuff, let’s get to the happy time of Jefferson’s first term. The program gets enacted. First term we get in, boom, the taxes come down. About the only internal tax that was really kept to any degree was the tax on salt, but the tax system was just dismantled. As the tax system was being dismantled, you have the old Laffer Curve effect: revenues go up. Economic activity was stimulated during Jefferson’s first and into his second term as revenues begin to go up. Shipping begins to take off. Now, part of this has to do with another aspect of American history and that is, up through the Civil War, what happens in Britain usually determines what happens in America. Great Britain was willing to ease its rules on shipping and on port entry because the Napoleonic Wars had started and now Americans were able to engage in a very lucrative carrying trade between British and French colonies at the time. And in instances where tariff was going to be the major revenue source, and Jefferson does lower it modestly, that’s going to help enhance the revenues of the day. The debt was well on its way to being reduced. The only thing that kept it from being reduced fully under Jefferson’s entire presidency was, of course, the purchase of Louisiana. But Louisiana was a steal at only three and a half cents an acre – that’s a pretty good real estate bargain, and he got New Orleans too. When all was said and done, this was not necessarily a bad deal and Jefferson thought that if there had to be debt, then this was not a bad way to underwrite it. Recalling ambassadors from overseas and reduction in the military and in the standing army proceeded apace. Though the Jeffersonians were a little more open to naval expansion, they never really expanded it very much. They probably threw this out as a way to keep some of the Federalists in Massachusetts quiet about vulnerabilities that were in our navy at the time. And of course, commerce had grown up. It seemed as if reciprocity might be happening. Unfortunately for the Jeffersonians, they probably thought reciprocity was more of Europe’s need for them at any point in time rather than Europe’s need for their goods and services during times of emergency such as the Napoleonic War.

But there were a few flies in the ointment that would stick with Jefferson. One of the flies in the ointment was having to deal with the Bank. Albert Gallatin really liked the Bank of the United States because it was convenient. Jefferson actually proposed a number of different things. One thing he proposed was an independent treasury. He said, “Hey, we’ll go ahead and issue treasury bills. We’ll pay them back in specie (precious metal, typically gold) and that’s how we can do the government business and even attach an interest rate to them and collect them for taxes.” Gallatin is like, “You don’t want to do that. We’ve got a bank. We already have somebody who can collect the taxes for us and tide us over with loans.” Jefferson’s like, “We don’t want a bank. Here’s what we could do. Why don’t we break up the bank and then give the assets of the bank to good Jeffersonian Republican banks” – pet banks, much like Andrew Jackson would do later on. Gallatin’s like, “You don’t want to do that.” Gallatin was probably horrified because, as you’re going to find out from the pet banks, they weren’t exactly responsible with the assets. Gallatin just liked the Bank. It was convenient, it was in place, and under Gallatin’s supervision, the Bank did fairly well. The Bank’s capital increased. He kept note admissions down to a degree. The other thing that Gallatin promised Jefferson was this: “If any bank of issue gets out of control and begins to threaten the stability of the Republican movement, we will crush them. So, don’t worry, I’m in charge. We’re going to take care of this. The Bank won’t be an issue.” But Americans were extraordinarily credit hungry. So, while the Bank of the United States acted fairly responsibly as a bank, you begin to see chartered banks spring up like mushrooms in the first decade of the 1800’s. Around 1800 there were six, maybe seven chartered banks. By the end of the decade, there’s 206, all lending on fractional reserves for the most part. There are a few good private banks that are very good banks, loaning out specie or loaning out notes fully backed by specie. But you do begin to see a movement because of this credit hungriness that is occurring in America and also at the State level: “There’s a chance that if we can’t have bills of credit, we can have banks whose notes we could tax and enhance the revenues of the State government.” Nevertheless, Jefferson’s first term becomes in a sense a standard for other presidential first terms, with one difference; unlike Roosevelt or others who added to the government and passed enabling legislation, Jefferson began to dismantle very effectively. We’re going to see tensions in his own party are going to bring some of that down. Finally, what we will also see is that some of those tensions will be reconciled and we will see something of as close to a political triumph of the Jeffersonian program against political and economic consolidation as one can have in this imperfect world.

I’m going to say something good about Hamilton. In his own way, his vision for America is a truly principled vision, I would say the wrong principles, and what he’s thinking of is the future. There will be time that this country has to be opened up. Hamilton also recognized something that I don’t think a lot of Jeffersonians or Jacksonians recognized. No matter how you slice it, the United States was still dependent upon British credit for the expansion of its economic system and the expansion of its wealth. British pullbacks and British central banking policy often were one of the triggers for panics in the United States and for credit expansions in the United States. What Hamilton really wants is a good standing in the international credit markets, particularly with Great Britain, so that if need be in time of war or in time of public investment, he can draw on these resources. And the hope was that the good money of the Bank of the United States was going to drive out the bad money that would be issued by any State-chartered banks. That was not the case. In the decade of the Jefferson and Madison Presidencies, the State-chartered banks would issue a lot of bad money, but driving out bad money was one of Hamilton’s arguments. Curiously, they didn’t set up a complete monopoly for the Bank, outlawing all other banks and what have you, because they couldn’t. The State governments could still charter these other banks. And they were also afraid of any legal tender provisions for the currency because a lot of these folks, especially during Hamilton’s time, that support the Federalist party tended to be creditors. And legal tender laws tended to work against creditors in those situations. That certainly was one of the arguments. I don’t know if the argument is valid. I think ultimately it depends on what backs that paper currency.

Jefferson’s second Presidential term was not as good. The commercial restrictions due to the Napoleonic wars, both imposed by the French and the British, are coming into play at this time. So, the question is now that the United States is being closed out of markets or potentially closed out of markets, and also U.S. sailors and merchantmen are being lifted from U.S. ships, predominantly by the British navy. How do we deal with these things? A U.S. ship is fired upon in American waters in the Chesapeake Incident. So, how are these things to be dealt with and in terms of political economy? If the policy really is commercial reciprocity in trying to work as close to a free trade or low tariff situation as possible, how do we deal with this kind of thing? The British were also doing things like erecting paper blockades. They would say, “The coast is blockaded,” but they wouldn’t necessarily have ships right out in front doing it. They would be on patrol and paper blockades were supposedly illegal under international law, but the British position was, “When you have 800 ships of the line, you can make the rules. Until then you will have to live with it.” The Jeffersonian folks begin to turn back to an old policy that divides their ranks. Their attitude is, “Fine, nonimportation worked once. It will work again.” The Embargo Act is placed down and it says no U.S. shipping is going to leave to trade with any of these powers anywhere at anytime. “We’re withdrawing from the market and you all will be sorry. And the Milan and Berlin Decrees will be lifted and the Orders in Council will be lifted and you will play nice with us because you will miss our goods and you will miss our wonderful Yankee merchants in the carrying trade” (who would sneak out anyway.) But when all was said and done, that was the idea, to shut it down completely.

Jefferson’s administration had relied and depended on John Randolph, especially concerning economic issues. There were a number of Yankee legislators who commented that they were surprised at how well Randolph understood these types of issues. Randolph gets really incensed. Now, he was incensed over a number of things, but I’m just going to focus on his anger dealing with these regulations. Randolph’s view is, “This embargo is absurd. What we’re basically doing is cutting off our nose to spite our face.” Though he also said we’re “cutting our jugular,” we’re cutting the carotid artery, we’re doing all these terrible things to ourselves. And he pointed out the price deflation that occurred in the agricultural markets that was hitting the Jeffersonian districts the hardest. If Jeffersonians had a strong power base in agricultural areas, it made no sense to impose an embargo that was going to knock down the price of tobacco, rice, and other goods that were shipped overseas. Nevertheless, Jefferson and Madison see this as a moral obligation and moral argument to be won here in international law. This is a sacrifice that has to be made for the greater good further down the line. From Jefferson through Madison some form of non-intercourse and using trade sanctions to try to impose your will upon another party was going to be used. This is a good example of a rather pacifistic policy, because there were Jeffersonian-Republicans North and South who favoured war rather than embargo. The irony is that if you look at all the acts that were put in place, the policy probably worked. The British were sending over a ship carrying a message that they were going to accept U.S. terms for the reopening of ports in order to avoid war. The embargo was hurting the British economy enough that reinvigorating trade with the United States was worth their effort. Unfortunately, a U.S. ship carrying our declaration of war crossed the Atlantic at the same time as the British offer to negotiate.

Why didn’t the Madison administration wait and let the embargo take its effect and peacefully force a change in British policy? Simple – the Congressional war-hawks, men like Felix Grundy of Tennessee, Henry Clay of Kentucky, and John Caldwell Calhoun of South Carolina. These men saw the depredations of the British Navy against American shipping as an affront to national honour. In their view, this had to be opposed militarily. There were other reasons. For one thing, these men’s constituents, particularly Grundy’s blamed their economic troubles on the British Orders in Council, believing that those had directly caused large and immediate drops in prices for American commodities. Expansionist motives were also at play. Canada’s just sitting up there, ripe for the taking. Randolph even mentioned this, describing the pro-war congressmen’s arguments as, “the whippoorwill cry, ‘Canada, Canada, Canada!’” Jeffersonianism had taken on a Scotch-Irish attitude: “We’re gonna to defend our honour, we’re gonna do it with arms, and there’s Canada sitting there like ripe for the plucking.” Why didn’t Madison hold these guys off? Well, for one thing, they were very able, and they quickly rose to leadership positions in the House. Another factor was Madison’s own weakness, his weak character. In a sense, Grundy, Clay, and Calhoun were much stronger personalities and much more vigorous in their arguments. Basically, Madison cracked. He crumbled. The Congress seemed to be rallying behind the war-hawks, so he agreed to go to war with the then-foremost military power in the world, which was busily occupied with beating Napoleon like a drum. The thing is, wars tend to be bad for the economy, and for the United States this proved true in 1812.

Now, Albert Gallatin had tried to save the first Bank of the United States before the war, but he couldn’t do it. So, he began to tell Madison that a central bank would be vital for carrying on the war. However, a lot of the war-hawks and their constituents and people in Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania were heavily influenced by the chartered State banks, and the chartered State banks wanted to get rid of the Bank of the United States, which they viewed as a credit snob which refused to expand its credit operations in a way that benefited State-chartered banks. The argument that was made was an interesting one. They said, “Hey, we can get rid of the Bank because, if you look at the aggregate capital of the State-chartered banks, it’s much larger than the capital of the Bank of the United States. Therefore, let’s go ahead and get rid of the Bank of the United States, and we’ll rely on State-chartered banks to underwrite the war.” Things didn’t work out as planned, however, because the numbers that were quoted in the speeches tended to be overinflated, and a lot of the State-chartered banks that should have been counting their deposits as liabilities were counting them as assets as well. So, to finance the war, the government issued stock (what we would think of as war bonds). When the war went bad, this government stock plummeted in value, selling for 60 cents on the dollar. Then, the government tried issuing treasury notes instead, some interest-bearing and some not. Those that were interest-bearing included the implied promise of paying in specie, and they tended to do well as a circulating medium of exchange, though not everywhere. Toward the end of the war, the State banks couldn’t meet the burdens and those south and west of the Hudson ultimately collapsed. The New England banks, which weren’t spending one dime on government bonds, did very well. Their money was solid and their issues traded at par with specie during this period. These events led many Jeffersonians to believe that the Bank of the United States hadn’t been so bad after all. They began drifting away from their principles about the worries of banks and their concerns about economic and political consolidation.

This eventually led to the rebirth of the Bank. The story is a long, convoluted one, involving Pennsylvania financiers like Alexander James Dallas working with congressmen like Calhoun to try and figure out what would be the best bank they could devise for a number of purposes.[2] First, to help finance the war operations, and second, to bring some discipline to the State-chartered banks by collecting their notes and turning them in for redemption in order to discourage the banks from over-issuing their notes. Calhoun fought fiercely for restrictions such as full-specie payment on the notes of the Bank of the United States. He also wanted federal legislation that would have required State banks to operate on a full-specie system, and toyed around with the idea of treasury notes being issued by the Bank as circulating notes. Alexander Dallas refused on all points. Bill after bill either died in committee or on the floor. It wasn’t until the end of the War of 1812 that the Bank was finally revived. The Bank had broad support because it was designed to be a specie-based bank that would honour its notes in specie. In 1816, Congress also passed a protective tariff, a strange measure for Jeffersonians to support. One reason for this was the idea that New Englanders had borne some of the brunt of the economic damages of the War of 1812 because their shipping had suffered tremendously. The tariff was viewed as a good-faith effort to New Englanders who had diverted their capital into home manufacturing to make up for the loss of British finished goods. The other reason was national defense. A protective tariff, it was argued, could help those industries, particularly textiles, that were crucial to national defense. Ya gotta be able to make uniforms, right? There were also gun-works, smithies, and things of that nature. Another motive was that the tariff would produce revenue that could be used to fund an American navy, a navy which could cast a blanket of protection over commerce, which would further aid New England’s economic recovery.

Many Southern Jeffersonian-Republicans crossed the aisle and voted for the Tariff of 1816. But there was one rather rascally fellow who simply refused to do so. His name was John Randolph of Roanoke. Randolph had opposed the War of 1812 and lost his House seat because of it, though not for long. By the end of the war he was back in the saddle again, and he began to pick up on some argument that John Taylor of Caroline had advanced in previous decades. Among these was the extreme danger of putting any faith in the Bank of the United States to rein in the State-chartered banks. In one of his speeches Randolph essentially argued that every man in the House was a stockholder, an engraver, a printer, a debtor, or in some way dependent upon the State banks. Was it sane to think that the Bank of the United States would impose any sort of discipline on them? The pressures would be enormous, he said, for the Bank of the United States to pursue an inflationary policy. In striking language, Randolph said: “You might as well take a pocket-pistol and attack Gibraltar as get up in this House and speak against banks!” He was not happy about the tariff, either, and in a number of instances he rose and declared a willingness to protect commerce, the handmaiden of agriculture. However, he was vehemently unwilling to protect domestic industry. “I loathe manufacturers,” he declared, “because they are the citizens of no place, or rather of anyplace. But you ring the fire-bell and their number assembles in the square, seeking any emolument or privilege they possibly can.” Sounds like global corporations, doesn’t it? Randolph’s real problem, then, was that these folks lacked the patriotic loyalties for which the protective tariff was being enacted. Their loyalty was to having their investment underwritten by the government and to shut off any sort of British competition, especially in the manufacturing of textiles. Despite Randolph’s fierce opposition, the tariff passed, and passed with the support of many Southerners, because it was a small tariff, only mildly protective, and temporary.

Jeffersonians had previously been strongly opposed to any kind of federally-funded internal improvements, considering them unconstitutional. That changed after the War of 1812, with a bill funding roads, harbour improvements, and other such things flying through Congress. Despite having signed off on the unconstitutional Bank of the United States (which he’d fought against in the previous century), and on the unconstitutional 1816 tariff, President James Madison suddenly developed Constitutional scruples and vetoed the internal improvements bill. It was his last major act as President, and everybody was stunned. Alexander Dallas was particularly shocked. Perhaps it was a sign of good things to come.

John Randolph’s predictions proved prophetic. The Bank of the United States underwrote massive inflation in the U.S. economy. Massive pressure was brought to bear on the Bank by members of Congress to do, supposedly so the country could recover from the War of 1812 by means of cheap credit throughout the Union. The Bank of England embarked on an inflationary policy about the same time, and British credit had a large influence on the American economy. Curiously, if you look at Bank of England policy it tends to match up with our panics and recoveries during the antebellum period. In any event, the Bank of the United States soon found itself in trouble. Its reserves dwindled fast and it encountered difficulties getting specie from the Bank of England in order to meet its obligations. Some branches, especially those in Maryland, were expanding their credit very rapidly through loans. The result was the Panic of 1819, and this was a wake-up call for many Southerners and many Jeffersonians because the agricultural districts got hit very hard. Many of them had gone ahead and taken out loans from the State-chartered banks. They had also been paying the revenues going into the federal government via the tariff. Curiously enough, from a little north of Philadelphia up to the border with Canada, things were pretty good. Northeastern regions were not hurt that badly by the Panic of 1819. Some of them weren’t touched at all. This made many Southerners suspicious. Suddenly, vast numbers of Southerners became hard-money, anti-paper-currency people. In 1820, new tariff legislation was introduced to Congress, which made Southerners even more suspicious, because the proposed bill would ratchet the tariff up rather than repealing it. This happened again in 1824 and famously in 1828 with the Tariff of Abominations. John Randolph looked like the most insightful person in the United States. Daniel Webster wrote a letter in 1824 noting that many people in Massachusetts (which had been an anti-tariff State up to that point) were beginning to invest capital into manufacturing because they perceived that tariffs were the way of future. This, Webster wrote, would lead to new political alliances and divisions. He had previously been pro-commerce and anti-protection, but starting in 1828 he became a vocal and eloquent defender of the protective tariff system.

The Tariff of Abominations also represented something unique about the evils of consolidated government. For example, Martin van Buren was, in some ways, one of the most brilliant evil geniuses to ever exist. Van Buren became the genius behind log-rolling. Now, his purpose wasn’t consolidation. In many respects he acted the good Jeffersonian, but in this case, he formed a coalition based on utterly false premises. He went to congressmen from the Northeast, the Middle States, and the South, asking them, “How high will you go on a tariff? Let’s make this thing so bad that nobody in his right mind is ever going to vote for it! We can throw this out as a sop to the Pennsylvania manufacturers whose votes we need, and when it fails, we can tell them we tried.” Imagine van Buren’s horror when Congress passes the darn thing passes, John Quincy Adams signs it into law, and incoming President Andrew Jackson refuses to veto it! This was a real wake-up call for Vice-President John Caldwell Calhoun. Calhoun was a moderate man, deeply devoted to the Union, one who viewed himself as seeking to restrain radical forces in his State while seeking ways to make the Union benefit and burden all of its members to an equal degree. His argument for nullification, born out of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, was not a secessionist argument. It was an attempt to find a lever to stop the economic consolidation that was going to use the productive wealth of one section for the benefit of another section, and Calhoun argued it that in way and in that fashion. Unfortunately for Calhoun, he was dealing with a President who grew up in the back country in the Scotch-Irish culture. Of course, part of that culture is the Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, chieftain-of-the-clan type culture where loyalties are very fierce to kith and kin. Nobody knows what Jackson himself thought on the economy. He hated the Bank of the United States, which he saw as an extraordinarily privileged institution (he also despised the Bank’s president, Nicholas Biddle), but he didn’t view protective tariffs as unconstitutional. Coming from a culture where loyalty is supreme, a strongly patriarchal society, any show of disloyalty among cabinet members or supporters would be viewed as an egregious insult and would have been viewed as a greater evil even than fighting against one’s own principles. In other words, Jackson took things personally, and when he found out that Calhoun authored the South Carolina Exposition and Protest, Jackson did not take it well. Indeed, he talked of using the Force Act to arrest and hang Calhoun. Andrew Jackson is an interesting figure in all this. On the one hand, he led an assault on the Bank and began dismantling much of the economic consolidation that had already been achieved. He also signed into law compromise tariffs that began the process of bringing the tariff down to revenue levels. But the thing about men like Jackson, Henry Clay, and Felix Grundy is that interparty rivalries were beginning to appear. The Whig Party emerged as an anti-Jackson coalition, and the political struggles of the day were as much about personalities as about policies.

Given all this, how did the Jeffersonian program emerge triumphant? It’s a curious story. Jackson set about completely paying off the federal debt. He also did what Jefferson had previously suggested – he attacked the Bank of the United States, took its assets, and divided them up among “good” pet banks. Some of the pet banks were well-managed and operated. Some (especially the one in Baltimore) were not. The Baltimore bank was run by Thomas Ellicott, and he had the bad habit of loaning money out to anybody who applied. He also had no care about redeeming specie payments. He just mismanaged the bank terribly. Secretary of State Roger B. Taney said, “Hey, we’ve gotta do something about these people! They’re fueling speculation all over the place!” The other problem with the pet banks was the government’s inability to enforce discipline on banks out west. Banks in Mississippi and the Northwest territories were lending out money without reserve capital, with some very cozy relationships between State legislators and the boards of banks. Then the Panic of 1837 hit. There are some interesting debates over what caused this panic. Some have blamed Jackson, saying getting rid of the Bank of the United States was the cause. Others have argued that trade shifts caused dry-ups of Mexican silver that had been flowing into the U.S. and fueling land sales. But if you look at the Bank of England’s monetary policy, you’ll notice that the Bank of England had raised its interest rates, and investments that had been going into the South, particularly cotton lands, were drying up rapidly. The banks had been pyramiding their note issues on top of those investments (or the expectation of those investments). When those dried up and people began to redeem their notes – boom, the banks are bankrupt. The Panic of 1837 led to a major backlash against fractional reserve banking throughout the country. In Louisiana and Mississippi, laws were almost passed completely banning “banks of issue,” and across the Union, more stringent reserve requirements were laid down. Ohio, of all places, completely outlawed banks of issue, meaning that no State-charted bank in Ohio could issue its own currency. Only private banks were allowed to issue notes, and they had to meet reserve requirement that were exceptionally high. The back-country districts that had been inflation-hungry got burned very badly in 1837, and they reacted very strongly against inflation as a result.

The U.S. government was now in a terrible position. How could they handle tax revenue and tax collection if many of the banks, including many of the pet banks run by its own people, were untrustworthy? The Jeffersonian ideal of an independent treasury was suddenly resurrected. The Treasury Department would handle governmental financial operations through the issue of treasury notes that could be used to pay taxes and were fully redeemable in specie. By the 1840’s, the independent treasury system was in place. President John Tyler, a Jeffersonian’s Jeffersonian, sparked anew the idea of spreading the Union from the Atlantic to the Pacific. By this point Texas is independent and seeking admission into the Union. About this same time, abolitionism begins to rear its head in a fascinating way. You see, over the 1830’s the newly-emerging Whig Party had dedicated itself firmly to the American System of Henry Clay, favouring a high protective tariff, federally-funded internal improvements, and a central bank. The idea that Texas might come into the Union and throw off the balance of power in Congress and perhaps the Senate too if Texas were divided up into multiple States, threw many Whigs into a frenzy. When James K. Polk succeeded Tyler as President, the drive for westward expansion ramped up even more. Polk was aggressively expansionist and very belligerent. He essentially told then-Secretary of State John C. Calhoun to tell the British to get out of Canada if they wanted to avoid war. Calhoun responded that you don’t negotiate with the most powerful empire on earth in that fashion. Polk also pushed hard for and eventually engineered a war with Mexico. Many Southerners, most notably Calhoun, fiercely opposed the Mexican War, fearing that militaristic expansion would transform the United States from a republic into an empire, just as had happened to ancient Rome.

Northern opposition to the Mexican War took an interesting tone. They began using a term in the 1840’s that became more and more popular over the course of the 1850’s – “the slave power.” A major Northern criticism of the war was: “The slave power has brought us into this war to expand their territory and their influence.” Indeed, the Whigs had been deeply bothered by the fact that, with Andrew Jackson out of office, they had nothing but their dedication to the American System holding their party together. They were struggling to hold back the Jeffersonian tide. By 1848, sectional division was beginning to appear and the national party system started fraying at the edges. Texas had come into the Union as a State and a great deal of territory had been brought into the Union via the Mexican Cession, particularly the territory of California. How should this new territory be handled? The Missouri Compromise had previously established the line for slavery. Would that line be extended on to the Pacific? In an odd twist of history, a Democrat, not a Whig, stirred up the issue. David Wilmot of Pennsylvania added a proviso to a funding bill that would have outlawed slavery in all of the newly-acquired territory. This became a curious debate. Slavery already existed in Texas, and Oklahoma was still Indian Territory. Who was going to take his slaves and move out of the Mississippi Delta into Kansas or Nebraska? As much as 30% of the arable land in Mississippi had yet to be brought under cultivation before 1860. This being so, why did the South get so upset about the Wilmot Proviso? If Southern planters knew it was highly unlikely that people were gonna get in the wagon, load up a hundred slaves, go West from the Natchez trace and set up a wheat plantation in Kansas, why did they care so much?

The argument, in my view, centers around a very simple fact. The Jeffersonian program was in place by 1848, and tariffs fell throughout the 1850’s. The independent treasury system worked well. The debt was at a manageable level and beginning to come down. But suddenly there was an insertion of the irrational into American politics. If you were a Northern Whig, what issue do you have left to run on? You’ve lost consistently on the central bank vs. the independent treasury, lost on the debt, lost on the tariffs, lost on the internal improvements spending. The only issue you have left is slavery, because it serves two purposes. First, it awakened many Northern politicians to the fact that, when it comes to republican democracy, numbers are everything, and control of the new western territories was gonna be crucial in determining who controlled the House and Senate. If you tell Southerners they can’t take their slaves into the new territories, it raises at least one more barrier (plus the geographic barrier) to them doing so. Southerners were angry because they saw this scheme for what it was – a power play designed to gain control of the federal government. Second, there was what was going on in the Midwest, which had been swept by a number of religious revivals, many of which centered on how God handles nations. As it turned out, they figured God was angry with America because the wheat market was collapsing in the 1840’s and 1850’s. Midwestern farmers ignored the recent technological improvements in agriculture and the increase in global wheat production in places like Ukraine, Russia, and Australia. They were convinced (and convinced by their politicians as well) that “the slave power” was doing this to them. No central bank to give them credit, no federally-funded internal improvements to reduce the costs of transportation, no protective tariff – “the slave power” is enfeebling them. Moreover, God is angry at the nation because of the blight of slavery. Avery Craven covers this in a chapter of his book, The Coming of the Civil War. So, there is an insertion of the irrational into American politics, but there is a rational reason for it – who gets to control the federal government by controlling migration into the new western territories.

One might ask why the South seceded in 1860-1861. Lincoln gave his guarantees. Could his economic program, the old program of the Whigs and of Alexander Hamilton, really be successful? It might not have been successful in 1860, but given time, a very short time, it could well have been. The other fear was that Lincoln was a regional President. It wasn’t a national party that won the White House, but a party that come from one region. That boded ill. If that didn’t spell danger, I don’t know what could. Slavery was an issue, but it was not the only one. The tariff was an issue, because the South was paying a great deal of money, 80% to 85% of the total federal revenue and getting virtually nothing in return. Ultimately, I think secession had to do with political calculus and representation. It also had to do with the North going after the slavery issue because it was the only one left on the table. The American people, North, West, and South, at least seemed to prefer a broadly Jeffersonian program. The people wanted to expand territorially, they wanted to keep the independent treasury, and they liked having lower tariffs. As much as an issue can be decided in the political realm, those issues had been, and the Whigs had lost decisively. All they had left was slavery.

Much of the story still needs to be written concerning exactly how this Jeffersonian triumph was achieved and why the Whigs felt unable, even when they won the Presidency, to go after the Jeffersonian program. Had Jefferson been alive in 1860, he would have been unhappy about a lot of things, such as the power of the federal court system, but he would have been pleased with a great deal, too. The Union had won a place among the nations and had incorporated itself well into the Atlantic trade nexus. The debt was low and manageable, possibly to be paid off. Tariffs had come down. The independent treasury was running well and operating on a sound-money policy. Then came catastrophe, and Hamilton’s phoenix rose from the ashes.

[1]John Randolph to James M. Garnett, 14 February 1814. See William Cabell Bruce, John Randolph of Roanoke, Vol. II, 622. https://archive.org/details/johnrandolphroa01brucgoog/page/622/mode/2up

[2]Not to be confused with the U.S. naval officer of the same name who is probably most famous for establishing the Pensacola Navy Yard and for marrying the sister of George Gordon Meade.

Note: The views expressed on abbevilleinstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.