‘Union’ neither denotes nor explicates a form of government. It is a word estranged in both the commonplace and the legal arts. There is no constraint to the daily rumble of social or personal definition. Any two or more people can form a ‘union’, even without using the word. At law ‘union’ is not a term of art. Rather it is defined by other words in the writing. Or, perhaps, not defined at all.

Sovereignty is not Union. Sovereignty is the crux and life-blood of self-government. Our personal independence originates inherent in our creation by Nature’s God. It is how we resemble our Creator. ‘Union’ provides only an illusion of sovereignty.

Our governments receive power to govern from us. They have no inherent independence. Without our personal sovereignty, our governments are deadwood drifting without center or character, condemned to idle in place and attempt the illusion they can survive without us. Sometime they will lockdown our talents and dreams and urn turn listing at sea. Then both we and our governments become prey to assault from within or abroad.

*********

“Union” is the talisman of the dominant party (Jeffersonians); and many Federalists, enchanted by the magic sound, are alarmed at every appearance of opposition to the measures of the faction, lest it should endanger the “Union“. Letter of Timothy Pickering to Gouverneur Morris, October 21, 1814. (emphases added) Both men were leaders in the then ongoing struggle to have New England and New York secede.

“I believe from the bottom of my soul that the measure (the 1850 Compromise) is the reunion of this Union … Let us forget popular fears, from whatever quarter they may spring. Let us go to the limpid fountain of unadulterated patriotism, and, performing a solemn lustration, return divested of all selfish, sinister, and sordid impurities, and think alone of our God, our country, our consciences, and our glorious Union – that Union without which we shall be torn into hostile fragments, and sooner or later become the victims of military despotism and foreign domination.” (emphases added) From Henry Clay’s “1850 Compromise” speech, February 6, 1850.

The Americans of the British colonies were proud British subjects. They were an integral part of an ethos of global strength and security. They believed themselves fortunate to be British, in lineage and law. Their colonial governments self-governed in most of their daily affairs. But each colony, whether Royal or not, was under King and Parliament. Sovereignty did not reside in the English people or the people of any colony in the realm but in the Central government of King and Parliament.

When the American colonies threw off ties to King and Parliament, they decided sovereignty under “Nature’s God” would reside not in any form of government but in the people who formed their own governments. Sovereignty of the people means the State is servant to everyone together while respecting any of us who stand alone. In this way, no one is an island.

***********

The July 4 Declaration was not the creation of a new country. It was 13 newly self-created countries announcing in unison their severance from their former sovereign: nothing more, nothing less.

“The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America …

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, …. in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, …. are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown ….”

War had begun the year before. Urged by their desire to survive, these new sovereign States must begin the business of creating a shared governance among themselves. None could safeguard independence alone. We struggled to define not Massachusetts or Virginia sovereignty, but what American sovereignty meant with them together. War caught us nibbling at the inbred boundaries of the States. The word ‘Union’ helped blur the chartered lines of culture, economy and religion. The war must come first. We would acknowledge differences in time.

Two American Constitutions came in rapid succession. Each made a conscious attempt at “Union”, and “Union” became the tell-tale word for the American States. But in 1861 our romance with ‘Union’ erupted into internecine war. The long-time struggle disguised as ‘Union’ ended in 1865. We were back to King and Parliament. Though its definition changed on the battlefield, we stubbornly kept the word and its notion. We had relinquished the sovereignty of our once independent States to the central government without scrubbing clean our words for governance.

The 1781 Articles of Confederation

“The FUNDAMENTAL issue in the writing of the Articles of Confederation was the location of ultimate political authority, the problem of sovereignty. Should it reside in Congress, or in the states?” Merrill Jensen in The Articles of Confederation, p. 161, The University of Wisconsin Press, Box 1379, Madison, Wisconsin, 1970. (emphasis in original)

Washington left to command American troops in June, 1775. The Articles would be written under the dire duress of war: mangled bodies and mangled estates. The Founders and their families were staring at utter ruin.

Dismantling themselves from the British government, the new Peoples felt the bracing air of self-government. It intoxicated them. But the situation of each State was different. Virginia had preeminence, Massachusetts was rising in commercial value and Georgia was still fighting Natives to stay alive. Every State felt they needed a “Union” lacing them together for survival.

In June, 1776, a committee began work on a paper of governance among the new States. Its writing fell to John Dickinson, who never wanted to declare Independence. He produced a draft on July 12. On July 22 the Congress went into a committee of the whole and debate began. No resolution could be achieved so the Articles went untouched till debate renewed again on April 8, 1777. On November 13 the debate ended and on November 17, 1777 the Articles went to the States for ratification. By agreement, unanimity was necessary for commencement of this new government. Authorization was due March 10, 1778. Yet Maryland, stuck in a land dispute, didn’t comply till March 1, 1781. The new States had finally forged themselves into a collegium of governance. Part of their new nomenclature was that they were a “Union”.

When on September 3, 1783, representatives of Great Britain and the American States signed the Treaty of Paris ending the Revolutionary War, the King and Parliament acknowledged the independence of each new American State by name. England no longer was a threat and each American State now stood internationally recognized as an independent Nation on its own.

*****

What did these American Founders mean by “Union”? In the Articles, the word ‘Union’ was used several times, most famously in the phrase “Articles of Confederation and perpetual Union between the States …”. It then repeats four (4) times more in the document. But what kind of “union” was it? Indeed, what kind of word is ‘union’ for government except poetry and propaganda?

The word is without legal meaning. Without grounding in definition, it is relegated to the poetical, mystical arts. The adjective “perpetual” denies understanding of human nature and human history. Were the Articles a republic, a democracy, a democratic republic? Was it federal? Some new ‘other’ form of unifying government? The Articles were silent. This new Union was fated to become whatever it could sculpted by political strife to become.

While Article 1 declares the name of this new government, ”The United States of America”, Article 2 settles the issues of power: “Each State retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence …” This meant that citizenship rested entirely within your State. No individual was a citizen of the central government for only sovereignty can convey citizenship. You were a citizen of the State in which you domiciled. No one was a citizen of the United States.

This State-Only citizenship brought a crucial distinction: citizens only voted for public positions within their own State. They did not vote for representatives to the central government. Their legislatures alone would vote for them. Your State government was the wherewithal of government allegiance. There would be no divided loyalty among the citizenry. Further, the Founders were not keen on Democracy. Each State set its own criteria for voting by their people. The central government had nothing to do with it.

Article 3 details what the States meant to be: “… a firm league of friendship (emphasis added) … for their common defense, the security of their liberties and their mutual and general welfare; binding themselves to assist … against all force offered to, or attacks made on them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade or any other pretence whatever”. War and survival were quite obviously the compass of their fears. Victory their first passion.

There was no Executive branch, no Judicial branch. It was a One Branch government: solely a Legislative central government. The structures of administration and execution of the laws were handled within the Legislature. Most critically: No powers were granted to the central government. All powers were delegated. The sovereignty of each State was left unshared. At law, what is delegated is kept by the giver and no part ever belongs to the receiver. Delegated power cannot be used except strictly as instructed by the delegator.

*************

Those wishing a nationalist central government had lost. The States were too new, the suspicions of leaders among themselves too deep. Their protections under the collective governmental habits of British sovereignty were gone. They had to learn to hunt and rut anew in a new world. Though their political cultures were varyingly British, their economic and social cultures had grown inherently different, even antagonistic. America was a sparsely populated frontier land with its own exigencies and expectations. There was yet no East or West. But there was North and South: two distinct precocious teen-age worlds now entwined by existential fears and dangers. And there was an adjacent, looming, untamed frontier, unfamiliar with British law.

The North was centered on shipping, commercial and financial enterprises. The South was structured on agrarian enterprises. When the South needed money to expand and/or sustain itself, it went North for those finances. When the North needed a market, the South was just nearby. Their cultures could appear complementary. But their reality was they were averse to one another with seeds of estrangement. The few years under the Articles are written in contentious argument and counter-punch.

The 1787 Constitution

“When fellow Southerners warned that a stronger Union would mean New England’s ‘tyranny’ over the South, Washington wrote, ‘If we are afraid to trust one another under qualified powers, there is an end of the Union’.” p. 3, Gore Vidal in Inventing a Nation, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2003. (emphasis added)

The nationalists had not given up their push for a nationalistic central government. In furtherance, they gave themselves a new name. “Although (they were) ‘nationalistic’, they adopted the name of ‘Federalist’, for it served to disguise the extent of the changes they desired”. Jensen at 245 These Faux Federalists engaged in intense collaboration to find their way back to a new convention for a new Constitution. Certainly Washington and Madison diligently conspired for a new Constitution. Washington had not been present at the debates on the Declaration or the Articles of Confederation. For the Constitution he, alongside Madison, came prepared. See also Founding Friendship, by Stuart Leibiger, The University Press of Virginia, 1999

In a twinkling Washington became Chair of the 1787 Convention. Each day he sat before them, his towering person reminding them of his and his Army’s sacrifices, a colossus balancing the weight of argument toward ‘Union’. Everyone understood he was aligned with the Faux Federalists in thought and vision. Inside and outside the Convention Hall he emanated an unassailably charismatic, national presence. The one time Washington spoke inside the Hall, his words became instant instruction: an unanimous vote passed his proposal for the number of constituents in a congressional district.

No one today can weigh accurately the immense power of Washington’s presence on and off the Convention floor. As much as in war, in 1787 in Philadelphia, Washington became the Father of his Country.

************

The question of ‘sovereignty’ burrowed through the Philadelphia arguments. The Faux Federalist empathy for expansive, cohesive, National government to wield innate, unassailable power was clear. The True Federalists were equally clear. They wanted sovereignty linked with subsidiarity which demands political decisions be resolved as close to local power as possible. The political war for the future was on.

The forthright attempt by the Virginia Plan for an abiding nationalist government (e.g., the national legislature could veto any State law) tottered. A truer Federalist structure was presented by New Jersey. It harkened back to the One vote per State of the Articles. Madison viciously attacked it and it became a plan with little backing. Even William Paterson who presented it later turned to support a more nationalistic government. Strong true Federalists like Mason of Virginia, Martin of Maryland and Gerry of Massachusetts went cudgel to cudgel with the likes of Wilson and Madison, Morris and Hamilton – all under Washington’s Shadow. The differences almost drowned the Convention’s course.

Then on July 13, 1787 something interesting happened: during the debate on taxation and representation, all about “small v. large” States, Madison rose to say he always “conceived the difference of interest in the United States lay not between the large and small (States), but the Northern and Southern States …” Wittingly or not, he had touched the brittle nerve of culture. Under Parliament and King, the differing colonial cultures were cloaked and massaged whenever needed. Britain never wanted war among its colonies.

Soon Morris, forever the realist, stood up aghast. “A distinction (he said) had been set up and urged, between the Northern and Southern States. He had hitherto considered this doctrine heretical. He still thought the distinction groundless.” But Morris went on that if the distinction were kept, “the Southern Gentlemen will not be satisfied unless they see the way open to their gaining a majority in the public Councils. The consequence of such a transfer of power from the maritime to the interior and landed interest (would be) an oppression of commerce … either this distinction is fictitious or real; if fictitious let it be dismissed and let us proceed with due confidence. If it be real, instead of attempting to blend incompatible things, let us at once take a friendly leave of each other.” (emphasis added) Gouverneur Morris did not want a Northern vs Southern dilemma haunting the Convention or what might come after. He would prefer to end the Convention without a new compact than continue and build a compact among incompatibles. Everyone shied away from that denouement.

His assertion of ‘incompatibility’ between North and South fell silently aside. Even Madison who had brought forth the stark contrast did not reply. Rather the Faux Federalists focused on seeding the Constitution with undeclared deceptions. Once they got taxation by the central government in place, they knew the ship of State was theirs. Hamilton became quiet while his fellow New Yorkers, John Lansing and Robert Yates, both true Federalists (and also brothers-in-law) had already left for home on July 10, 1787.

*********

Five agreements outline a blueprint to guarantee Nationalism’s eventual full sail: 1) how the new government would acquire governmental powers; 2) how representation would be effected; 3) the creation of a national Judiciary; 4) the creation of an Amendment Process which, though admittedly novel in the history of Constitutions, decidedly pitched the power to effect constitutional change onto the side of the central government in preference to the States; and 5) an Impeachment process for central government officials that effectively kept their denouement out of the hands of the States and solely within the power of the central government.

First: “Article 1, Sec. 1: All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States …” The States were giving away enumerated powers (Art. I, Sec. 8) forever, – because that’s what ‘grant’ means. With this grant of powers, the Nationalists now had at least partial sovereignty. The irony is that sovereignty was then, and even now, believed incapable of division. But once the Convention voted to “grant” rather than to “delegate” powers, Madison labeled it a new animal called “dual sovereignty”. The Nationalists were on their way to pervasive control

True, they enumerated what those granted powers were. And they enumerated what powers remained with the States. But at law what is ‘granted’ is gone. So, at law which is the rubric and fabric of the Constitution, the States in 1787, by granting and not delegating powers created a separate sovereign government, one whose powers, unlike their own, would affect and effect itself over all the States together. This could never have happened under the Articles where powers were always ‘delegated’. Every Founder understood it is in the nature of power to aggrandize and never relinquish.

They had created a tiger and its tail would come to whip them in the future. Yet they left the conflict to future generations to resolve. The North would resolve it one way. And the South another.

Second: “Article 1, Sec 2. The House of Representatives shall be composed of members chosen every second year by the People of the several States.” This divided a citizen’s loyalties. They would now vote for their national representatives where once their State legislatures did. But notice there is no requirement of citizenship. Citizenship was left unaccounted for. The Founders had quietly moved beyond accepting the States alone were gowned in sovereignty.

A bow to State sovereignty came with the election of the Senate. “Article 1, Sec. 3. The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, chosen by the Legislature thereof. … each Senator shall have one vote.” This gave the States some influence, even control, over central government legislation. But it was a power the States would lose with the acceptance of Amendment XVII in 1913: Senators would now be elected by the same hustling people who also elect the national Congress. The power of State legislatures was minimized by granting power to the everyday people, most all of whom least knew the needs of their State and the personalities of the Senatorial candidates.

Madison’s sovereignty compromise, ‘dual-sovereignty’, had become as surreptitious and dissembling a definition of political activity as one need imagine. For that meant the “people” now would have divided loyalties. What they might not get from one government, they could try to get from the other. The Founders not only introduced new political strife between a State and the central government but also within each State. No politician willingly shares power. No homeland populace willingly allows trespassers to rule their land. No one forfeits their birthright unless conquered, connived or contrived. But that is what happened … all under the guise of security against foreign intervention, economic betterment, peace at home … and taking a proper, hopefully one day, potent place among the counsels of nations.

By Washington’s First Inaugural on April 30, 1789, who could believe this “Faux Federal Government” would not grow into a far greater nationalism with the coming years? This was not a Union of 13 States as the Articles had been. It was a Union of 14 States, the 14th being the Central Government with supposed limited sovereignty.

The compelling truth was that the central government’s sovereignty took its power not alone from the distinct States but from all the peoples of all the States together. The “federal” government’s boundary encircled the entire peoples of the collective States. We had become not the Peoples of the States of New York, Virginia, etc. that is, the Peoples of the united States. Rather we had by our own constitutional law turned ourselves into “a Singular People” within a new Constitutional framework abiding all the States upon a framework of divided loyalty. So the Preamble begins “We, the People of the United States …”.

Gouverneur Morris, who wrote the 1787 Preamble, knew the cards he was dealing. He did not write “We, the Peoples of the united States …” Nor did he write “We the People of the State of New York, of the State of South Carolina, etc etc.” He was a Nationalist as were all the members of the Style Committee which included Madison. Every member of that committee believed in and wanted a national government stronger than any State alone, stronger than all the States together. To help their argument, they said it wasn’t so. Rather it was dual-sovereignty: a simple, unedifying, heralding phrase descriptive of continuous political warfare.

Then the Founders went further than granting powers to the central Congress. They needed someone to direct it. So they created an Executive, a President to administer laws and speak in one voice to the people. But the Executive needed a back-up, a storehouse of potent legal ammunition to champion a national position. The Faux Federalists created what True Federalists feared as much as a too-powerful President: national courts.

Third: “Article 3. Sec. 1: The Judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time establish.” This not only created a national Supreme Court of judicial activity but gave power to the Congress to seed its influence through inferior national courts wherever and however it would decide. This proliferation of national courts had the effect of enforcing national and nationalistic policies throughout the land. We should never accept the myth of non-political courts. The Judicial arm of the central government would be used to effect the power of national laws.

Everyone knew the history of royal courts in England had been to support the royal government. Henry II (likely him) meant to bring his reach uniformly throughout his land. To be sure, Kings threw out and replaced Judges fairly willy-nilly as a king might decide. So to insure (the Founders thought) that courts would be independent, they appointed national judges for life. Mason rose to limit federal courts to admiralty cases. He lost. The 1787 convention placed little thoughtful weight into Federal Judges. But history would demonstrate that Judges for life are an unbridled cacophony of diverse and conflicting political-judicial decisions: they are a government unto themselves. Yet themselves governed by the party who brought them to their robes.

Then the Founders implemented Diversity of jurisdiction. It’s a clever concept: if parties from different States are arguing their case in a State court, the case can be removed to a National (federal) court on the assumption that the State courts are biased against litigants outside their State. So much for the integrity of jurists … as if a Judge in a Federal court would be less susceptible to corruption than a State Judge. The point is that when the national government gains loyalty, a State loses loyalty. Eventually the State is considered inferior by its own citizens.

Fourth: Article V requires either two-thirds of both central government Houses or two-thirds of the States to agree on proposed changes to the Constitution before a Convention can be called. But that tumultuous Convention has no power to incorporate new changes. The process actually intensifies because the Convention’s results must be approved by three-fourths of the State Legislatures or by three-fourths of State Conventions whichever is proposed by the central Congress. That is rough and turbulent land for any political process. Interestingly both the “two-thirds” requirement and the “three-fourths” requirement were introduced by James Wilson, perhaps the most nationalistic of all the Framers.

Every political change in constitutional law by Amendment is in a strangle-hold from the start. And the States have no inherent power to opt out. The Houses of the central government are in charge.

Fifth: “Article II, Sec. 4: The President, Vice-President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” How this is done is spelled out in Art. I, Sec. 2 , Cl 5: the House of Representatives has the sole power of Impeachment. While in Art. 1, Sec. 3, Cl 6: the Senate has sole power to try Impeachments. Thus, the central government alone disciplines its officers. The States have no constitutional power to remove or discipline national officers within their own boundaries. Such appointees (some for their life’s duration e.g. Judges) have a fast step into despotism. What kind of “Union” is that?

*******

Governor Edmund Randolph of Virginia introduced the nationalistic Virginia Plan at the 1787 Convention. At the Convention’s end he voted against the new dual-sovereignty Constitution. Then, at the Virginia Debate for Ratification, he reversed himself and voted for this new Compact. His reason is interesting and goes a long way to understanding the myth-power of the word Union to corral the human mind and soul.

“Mr. Chairman, one parting word I humbly supplicate. The suffrage which I shall give in favor of the Constitution will be ascribed, by malice, to motives unknown to my breast. But, although, for every other act of my life I shall seek refuge in the mercy of God, for this I request his justice only. Lest, however, some future annalist should, in the spirit of party vengeance, deign to mention my name, let him recite these truths – that I went to the federal Convention with the strongest affection for the Union; that I acted there in full conformity with this affection; that I refused to subscribe, because I had, as I still have, objections to the Constitution, and wished a free inquiry into its merits; and that the accession of eight states reduced our deliberations to the single question of Union or no Union.” p. 652 in The Debates in the Several Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, as Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia in 1787, Vol 3 of 4, Forgotten Books, FB & Ltd. Dalton House, 60 Windsor Avenue, London 2015 (Emphases in Original)

In the final assay of the attendees in Philadelphia in that overly warm summer of 1787, only George Mason would refuse approval both in Philadelphia and in his Country of Virginia’s, deliberations. His reward was to become his neighbor Washington’s “quondam friend”. Their rich, enabling friendship which Washington had so profited from over the years turned into icy silence for the remaining 3 years of Mason’s life.

THE INTERIM

From the first Congress it was political and economic war, Northern mercantilism vs. Southern agrarian, Northern centralization v. Southern subsidiarity. While the South through its cotton, tobacco, rice and sugar ballooned the monetary value of the country, the North became the financial capitol though banking, insurance, shipping and infrastructure financed through Congress. Washington held the lid on the teapot. But in 1794 with the last days of his presence in sight, Senators Rufus King of New York and Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut, both luminaries in their own right, approached John Taylor of Caroline with a written proposal that the regions separate in peace – and the South could choose the boundary between them. The North v. South antagonisms were too much to bear. They wanted a peaceable severance while still possible.

The incompatibility Gouverneur Morris saw for the first time in the 1787 Convention had come home to roost. Taylor showed the written proposal to Madison who summarily jettisoned the idea. But had Jefferson won in 1796, leading men of New England like Morris, King, Ellsworth and Oliver Wolcott, Sr., would have fought to take New England out of the “Union”. Perhaps, Hamilton, against secession till his dying day in 1803, might have been able to hold New York and New England in the 1787 Union.

But separation was truly only a matter of time and enterprise: the meteoric rise of cotton opening the alluvial lands along the Gulf – mostly financed by Northern banks and creating wealth America could barely imagine; the capture of the national government by Jefferson and Madison in 1800; Jefferson’s purchase of the Louisiana Territory doubling the country’s land and opening the Mississippi to unimpeded commercial traffic; the rapid growth in commercial shipping in the North including its tenacious grip on the Slave Trade from Africa to points outside the United States, financed and insured by Northern banks and insurance companies; the populating of the Midwest and growth of new roads, towns, cities, canals, and the bridges over waterways; unimpeded immigration from Europe; the construction of trans-State railroads; the robust American Industrial Revolution in the mid-1820’s; the growth of a newsprint industry with daily and weekly newspapers flowing through the mails throughout the land. With all this came the spreading encroachment of the Federal government everywhere, its officials and judges entrenching throughout every State. And a Supreme Court under Marshall and Story who, among other matters, facilitated the financial submission of State banking to Federal law, insuring a growing federal dominance both in commercial and political issues. Americans were grappling among themselves for the old and new enterprises that were literally cascading wealth into their laps.

Then in 1833, along the trail of the “Abominable Tariff”, President Jackson signed the Force Bill aimed at South Carolina – but more truly at every State. It marked the first alarms of internecine warfare to engage federal troops to enforce laws harmful to one State or many. Madison, still alive, remained strangely silent. He had been in communication with the President. His silent nod must mean acceptance. A Southern President had just transformed the original compact: the central government became truly National. It was no longer a child of the States.

Near in time, rose a Northern abolition movement, blind in emotion and without virtue, specifically targeting the South though slavery and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade continued enriching the North. Abolition societies had first begun in the South and were varyingly effective since before 1800. But this northern version talked a faux spiritual war for change, for upending the Constitution. It rallied to violence as wax to flames. It was a seperatist movement and never popular among the Northern people. But it had the ear of politicians and men of wealth. A forever steady drumbeat of feel-good moral superiority culminated in a lunatic’s military action against a peaceful rail and river junction in Virginia. The stated purpose was to bring bloodshed to the South. The first murdered victim was a free Black man. Much more could be added. But Harpers Ferry signaled the end of Peace.

The 1861 Confederate Constitution

In April, 1830 at the Jefferson Day Remembrance Dinner (Jefferson was born April 13, 1743) two Southerners, one the President, the other the Vice-President, purposely raised their glasses to commemorate the Founder most aligned in the public’s mind with the seemingly inherent ideals of our country. President Jackson declared: “Our Union: It must be preserved!” Vice-President Calhoun put his glass to the toast and countered, “The Union, next to our liberty, most dear!”

Before 1860 those exclamations would turn into rifles and in 1862 President Lincoln settled the contest declaring. “I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be ‘the Union as it was.’ …” Lincoln to Horace Greeley, August 22, 1862. (Emphases added) This famously oft-quoted letter to Horace Greeley in 1862 makes clear that at war Lincoln grounded all his public intent on the Union of the States.

No one should doubt his words. Call it a cover or a shield, whatever you will, about some truer intent, Lincoln’s ineffable political ploy was a “mystical Union” of the States: “Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature. Lincoln’s 1St Inaugural, March 4, 1861 (Emphases added)

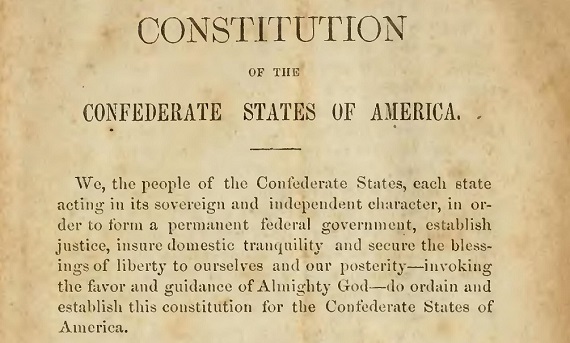

The CSA Preamble

The CSA Founders had 70 years’ experience where they witnessed the wringing and wrangling the 1787 Constitution could be wrung through. They had observed the growing numbers of people in deadly disagreement over the huge assay of wealth and power falling into the hands of politicians and new-fangled corporations. They experienced the power of national courts balloon to match the occasion. They saw how great the federal government’s footprint could dig into a State’s sovereignty.

“As the amalgam of warring forces concentrated on the issue of California in the early part of 1850, Robert Toombs of Georgia said vehemently, ‘This cry of the Union is the masked battery from behind which the Constitution and the rights of the South are to be assailed’. (We in the South) ‘took the Union and the Constitution together – and we will have both or we will have neither’ … Northern moderates believed Toombs and believed that he spoke for the Southern moderates who were open to compromise. But the moderates were not in power in either section; nobody was in power anywhere. The conflict, like a senseless argument that grows more serious on the exchange of words, was gathering its own momentum and nobody seemed to think of the consequences.” In The Land They Fought For – The Story of the South as the Confederacy 1832 – 1865, by Clifford Dowdey, Doubleday & Company, Garden City, N.Y. 1955; pp 36 -37 (emphasis in original)

Not oddly at all, the South chose neither Constitution nor Union. Nor is it odd the Confederate Constitution eliminates the word “Union” entirely. It’s nowhere in the Preamble and nowhere anywhere else. Poetry was leaving the hard-fist of politics.

But the South would write a new Constitution where Government would still come from the people and the purpose was clearly stated: “to form a permanent federal government”. On a third attempt, some Americans finally got it right. The South clearly attested to what we always stated we should be about: the free and peace-bound pursuits of a people. And not only that: we were now “invoking the favor and guidance of almighty God” to help us do so. The National Compact became a National call to Prayer.

A short comparison of the same 5 original agreements demonstrates how well the CSA Founders learned the historical lessons of the prior years.

First: “Article I, Sec. 1: All legislative powers herein delegated …” Not a word about “granted powers”. Nothing is granted. From the beginning here was a powerful brake on federal (central government) political forces attempting to legislate over the States at will. Sovereignty would remain entirely in the States. Any power of the central government could be revoked. The CSA federal government was without sovereignty. Subsidiarity finally took center stage in American constitutional law. Dual-sovereignty was dead.

Second: “Article I, Sec. 2: … the electors in each State shall be citizens of the Confederate States, and have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State Legislature; but no person of foreign birth, not a citizen of the Confederate States, shall be allowed to vote for any office, civil or political, State or Federal.” Only citizens of the CSA, whether born in the CSA or born on foreign soil, could vote for representatives to the national government. It was a recognition of the power of culture on government. Immigrants must learn what the country is about before having a say in its laws.

Third: Article III established a Supreme Court and inferior federal courts, but then curtailed the powers of the federal courts: 1) No Diversity jurisdiction except when a State itself originated suit against an out-of-State defendant. State courts were to be trusted with parties from different States but not entirely. Even subsidiarity must face the too obvious circumstance of possible prejudice. 2) No Equity practice in federal courts. The history of Equity (originally Church law) was a backdoor to overturn civil law. Married to subsidiarity, the CSA forbade federal court interference with State courts.

In the end the CSA never did establish a Supreme Court. The distrust of federal courts overtaking the national legislature or the jurisdiction of State courts rang too loud, too clear. Finally, the CSA would run out of time.

Fourth: Art. 5, Sec. 1, Cl. 1 established a procedure for Constitutional amendments run entirely by the States. The national government had no role except the mandate to issue a call for a convention when 3 States had already proposed amendments. There was no dual road to amendments. Only the sovereigns could manage this procedure. The central government was not a sovereign.

Fifth: Article 1, Sec 2, Cl 5, “….The House of Representatives shall have the sole power of impeachment except that any judicial or other Federal officer, resident and acting solely within the limits of any State, may be impeached by a vote of two-thirds of both branches of the Legislature thereof.” There would be no local tyranny by federal officers residing and operating wholly within a State. The CSA standard was always subsidiarity.

************

What the CSA Founders could not re-fashion was Time. Lincoln had decided to pounce even before the 1860 election. He never had room for compromise. He feared the Northern financial and commercial interests which founded, needed and led his sectional Republican Party. The Party had miniscule support in the South. The South for years had been paying the greater amount of the National government’s financial support for Northern dreams: over 70%. Lincoln could not allow such sums be lost to the Republican infrastructure. And, certainly, never be allowed to compete with Northern interests.

Lincoln was their man. He knew political survival. Had learned it from Henry Clay. But it’s extremely doubtful even a man with Clay’s persuasive powers could bring a compromise into the 1860 Union as he did in 1850. The Union was in a death spiral. Clay had stated he believed an abrupt and potent show of force would quickly crumble a State’s will to secede. He never imagined an internecine war. He thought a sharp confrontation would bring any State back into harness.

Is it possible to believe Lincoln thought differently? He abjectly followed Clay. Lincoln was often a leader, chosen in a backroom among other pols … but never an original-thinking leader. Always a staunch survivor, he had little public charisma till after his assassination. His world always balanced only on the present.

So after nearly a million deaths through harsh illness, starvation and battlefield carnage, the North got its wish. Without Southern demands for subsidiarity and fiscal restraint, especially with infrastructure, the Northern interests dominated national power. Its tentacles strengthened throughout the land – Maine to Oregon, Minnesota to Mississippi, Florida to California. There was no longer an anchor to hold back the power dreams of northern commercial enterprise. Everything came down to money. Soon as the CSA Constitution with its mandate for a low tariff had hit northern newspapers in March, 1861, the calls for war grew quickly and vehement. Yet there can be no just war for money. Such a war is murder.

The Aftermath

Around 1885, there grew the idea of a verbal pledge to the recently re-unionized country and its flag. An early version was a simple sentence: “We give our heads and our hearts to God and our country; one country, one language, one flag.” (emphases added) … just as the floodgates of immigration were opening.

Congress made changes till in 1954 under President Eisenhower, a final revision inserted the phrase “… under God”. The essential clarion became: “… one Nation, under God, indivisible …”. America was cementing Americanism, a new Secular Religion, begun under Lincoln, where the children and the adults at public events or in private societal meetings … wherever … now would say the same Singular Prayer of Union.

*********

In the early 1840s a young historian named Mellen Chamberlain sought out one of the last surviving participants in the Battle of Concord to ask him about that experience. The minuteman’s name was Levi Preston. He was 91 at the time. Mr. Chamberlain later recorded the interview in his work, John Adams, the Statesman of the American Revolution.) Reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, LLC (September 10, 2010)

Chamberlain asked Preston why he had fought the British. The answer wasn’t what the historian expected. For Preston did not speak of the oppressive British rule, the stamp tax, the tea tax or the writings of philosopher John Locke.

“Well, then,” asked Chamberlain, “why did you fight?”

Preston’s answer still takes our breath away: “Young man, what we meant in going for those redcoats was this: We always had governed ourselves, and we always meant to and they meant that we shouldn’t.”

It was not different in 1860: the South had no designs of conquest on other sections of the country. It wanted to govern only itself. The North wanted to govern North and South and East and West. And so the war, necessarily, came …