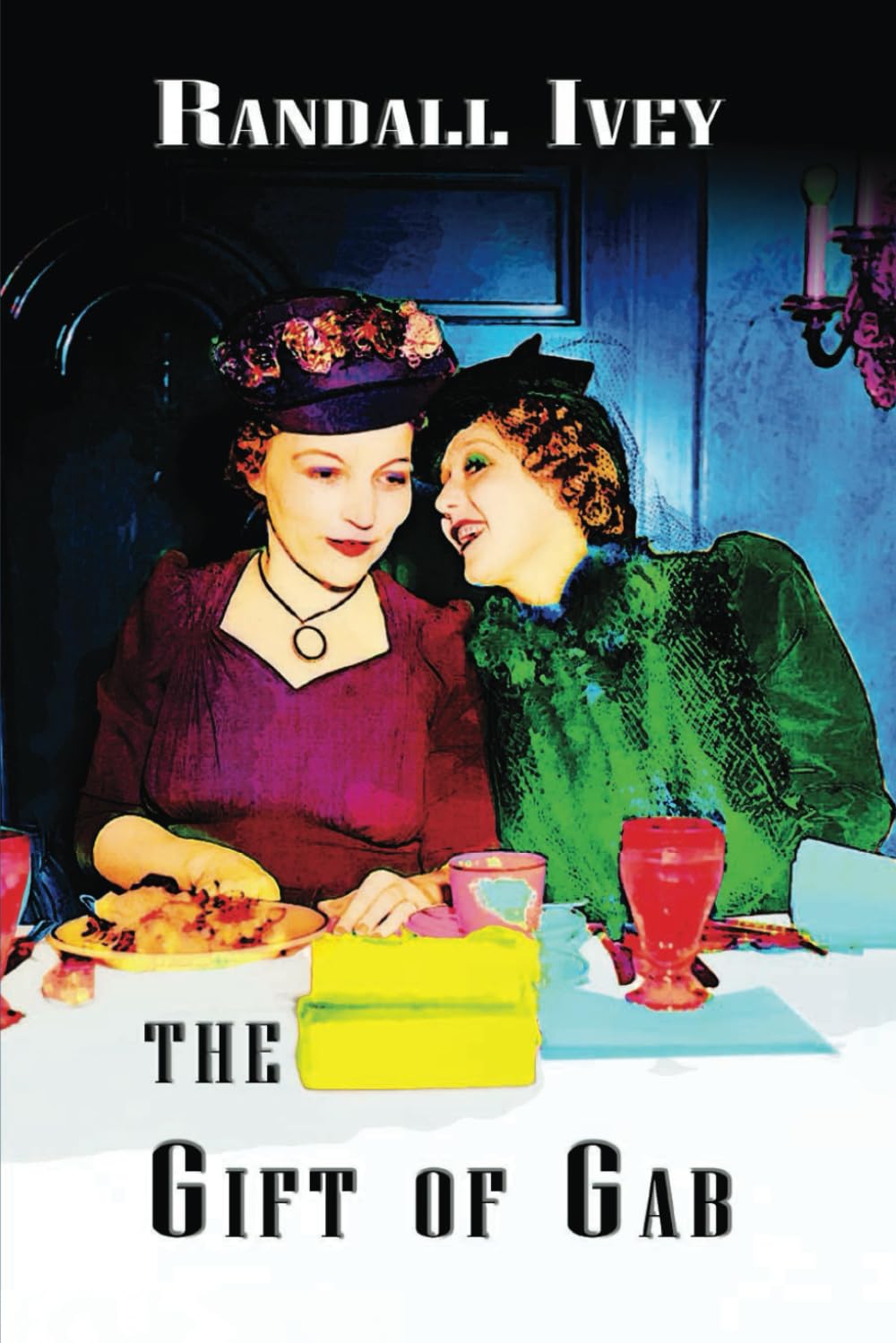

Review of Randall Ivey, The Gift of Gab (Green Altar Books, 2024)

Randall Ivey’s most recent collection of short stories is a welcome addition to his growing list of titles, and since four of the stories in The Gift of Gab were first published on the Abbeville website, many readers will already be familiar with his unique and wonderfully comic, often macabre and sometimes tragic evocations of life in Upcountry South Carolina. Like his previous collection, A New England Romance and Other Southern Stories (2016), the tales in the present book are mostly set in the mythical Compton County of Ivey’s homegrown imagination, and peopled by characters whose eccentricities sometimes border on the bizarre. Yet like so many of his southern literary forerunners, the keynote of Ivey’s work is sounded in the depths of the human heart, which he plumbs with a deft touch and a good deal of wisdom.

Ivey’s sure and loving sense of place is evident on every page of his work. Compton County is only three hours away from Charleston, but it might as well be on the other side of the moon, so different is the former from its opulent coastal cousin. Its history reflects that of Ivey’s own Union County, a place originally settled mostly by Scots-Irish Presbyterians and, later, hard-scrabble Baptists and Methodists. Many of those settlers and their descendants were cotton planters in the 19th century, most of them small, “plainfolk” farmers. By the late 19th century cotton mills became the predominant economic force in the county, though the last of those mills had shut down by the 1990s, bringing about a protracted period of economic decline that is frequently alluded to in The Gift of Gab. Most of Ivey’s characters are from working or middle-class origins, but class-distinctions do not seem to amount to much in Compton County. Racial distinctions, on the other hand, are sometimes more pronounced, but racial relations are, on the whole, more amicable than one might expect. Whether white or black, most of the characters appear to be churchgoers, and a shared religiosity contributes to an underlying moral consensus that is frequently evident in these stories.

Whatever else one might say of the people who populate Ivey’s fictions, most of them are not well-educated, and even those are who are speak in a similar, if more grammatical, Upcountry dialect. Ivey’s adroit hand at regional diction is one of the most memorable aspects of his story-telling. Characters often use terms that probably date back centuries—terms like “twicet” or “hissen.” (Hilariously, if you Google “hissen,” the AI response will inform you that it’s a “variation of “y’all.”) Others, perhaps not quite so venerable, are nonetheless distinctive—terms like “inseck,” “nanner puddin’,” “thowed,” “ort to,” “pert-near,” “onliest,” “lessen,” “leastways,” “worser and worser,” and “hisself” just to name a few. People in Charleston do not talk like this, though many Compton County colloqialisms are common across the rural Deep South.

Ivey’s modes of narration vary, but first-person is the most common. These narrators are always members of the community who see things from the inside, though their precise relations to the other characters is not always evident. Perhaps the most notable example of this is the book’s title story, which, like Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily,” is told in the first-person plural. The unnamed narrator speaks in the voice of the community, yet with a certain aloof disdain for those whose gossip unfairly destroys the reputation of one Miss Jenny DeGraffenreid, an aging widow whose late husband ran a local pharmacy. Miss Jenny herself is something of a gossip—of the benign sort, a “gabber” who spends her days chatting up everyone she meets. She “doesn’t discriminate,” we learn, “against who it was she talked to,” though she preferred men: “Liked ‘em a great deal and insisted they hug her before she talked to them and after, and if the man wasn’t careful … he might find Jenny’s hand sneaking down his back …and pinching a substantial portion of his rungunkus.” Yet this is all good fun, for Miss Jenny is really just as “naïve as a little youngun.” Everybody loves her for her kind-hearted ways, but that is what gets her into trouble when she forms a friendship with a young ex-con who works at the Pancake Palace and offers him a ride home late one night. The trip involves a twenty-mile trek into the deep piney woods where the young man, Rocky, lives in a double-wide with his slovenly wife and two kids. Miss Jenny is appalled at their way of life and frightened nearly out of her wits by the experience, even though she makes it home unscathed. The problem is that the story gets around and gets “twisted up and changed … by folks who only wanted to say something bad about somebody good.” In the most damaging version, Miss Jenny, Rocky and his wife all got uproariously drunk, stripped of all their clothes and danced wildly around the doublewide in the moonlight. When Miss Jenny finally hears of all this vicious tale-mongering, she never again steps out of her home except to attend services at the Methodist church. To one of the loyal friends who pays her a visit, she remarks, “It just don’t pay to be good to nobody.”

As readers we do, of course, feel sorry for Miss Jenny, but the narrator leaves us with an implicit understanding that her own “gift of gab” overrode her common sense and invited the ensuing catastrophe.

By contrast, “In Spring the Sun Will Smell Like Roses” is a first-person narration by a middle-aged woman who is quite isolated from the surrounding community. She speaks for no one but herself, though the tale is largely about her mother, a woman whose fear of the outside world is so profound that, after her husband abandons her, she contrives to stunt her daughter’s emotional development and to inculcate in her the same fear of outsiders: “Never give your trust to anyone,” she intones. “Nothing good comes from it. Nothing!” Terrified that her daughter will grow up and go out into the world, she takes her out of school and forbids her to read books or to form friendships with her peers. “You will always be your mama’s little girl,” she would say, and to reinforce the message would make her gifts of dolls, “a whole roomful of dolls … lined up against my bedroom wall like a line of girlie soldiers …staring like they expect something from me—a whole line of shiny eyes and shiny smiles and pretty dresses.” This dollification of the narrator daughter continues until she is well into middle age and her mother has grown tired and sick. When her mother arrives at the brink of death, the narrator panics:

“Mama!” I call out. There’s a catch in my throat. I’m crying. My heart and my brain know something they won’t tell me yet. Or maybe I just refuse to hear it.

“Mama. Haven’t I been a good girl to you? A good daughter?”

She doesn’t hear me. She’s gone off someplace without me. Maybe if I look where she looks and follow it, I can find where she’s gone.

“Mama, I don’t know what I’ll do here by myself.”

So I sit down beside her and watch her eyes and do my best to find out where she’s got to.

Thus the end of the story is at once pathetic and tragic. A mother, devoured by resentment and afraid of the world, reduces her daughter to infantile dependency. While Ivey refrains from explicitly drawing out the moral, it is clear that the tale is a cautionary one about the profound selfishness and even cruelty that has resulted in the narrator’s emotional captivity—one that may very well last until her own death.

Cruelty is the moral crux of several stories in this collection, and perhaps the most jarring is one called “The Dead Will Provide,” which begins in a comic vein but ends in tragedy. The first-person narrator, a young woman named Jasmine, is right off the bat revealed as a master of dry wit: “There could not have been anybody else in all of Beaslap, South Carolina, who loved a dead body more than Miss Semona Diggs.” In fact, Semona loves dead bodies because she loves a wake, and she loves a wake—especially black wakes—because folks in Compton County—especially black folks—are lavish with their culinary provisions: “fried chicken, backed chicken, ham and pork chops, barbecued ribs, green beans and collards, sweet taters, goat hash and deer hash, biscuits, rolls, red velvet ….” In an ongoing debate with her mother, Jasmine says, “Mama, … Semona Diggs goes to see dead folks just so she can eat their food. And that’s the only reason she goes.” Her Mama, more thoughtful, says, “You don’t know that.” But Jasmine, with the persistent self-righteousness of the young, is incensed at the depravity of Semona Diggs. Semona, she insists, is a complete hermit who never steps out of her house, but as soon as someone “drops dead,” she’s the “first one to show up.” But, again, her mother hesitates to judge: “Maybe this is the way that the Lord provides for Miss Diggs. Gives her the company she don’t ordinarily have.” At this, Jasmine scoffs, “She don’t want company. She wants a drumstick and thigh with a side of tater salad. Ought to go to KFC for that and leave the dead folks alone.”

The problem is that Jasmine and her friend Dee, who seems to be nursing some old animosity toward Semona, never consider the possibility that the old lady can’t afford KFC thighs and tater salad. They assume that she’s a sneak and a thief who pops up out of nowhere in a trench coat and a brown wig that hides her face and proceeds to shift the funeral baked meats into the inner pockets of the coat before vanishing with the goods. When Mr. Ernest T. Freeman dies, Jasmine and Dee, like most of the town, turn up to “enjoy the endless bounty of God’s great feast.” But when Semona appears in her usual getup, Dee asks, “You think she’s got anything on under that coat? Maybe she don’t have nothing nice enough to wear to a wake. Just threw a coat over her old naked body and came on.” Jasmine, shuddering at the thought, says, “I sure hope that coat don’t fall open.” Dee retorts, “If she is naked, maybe she ought to go right up to Mr. Freeman and flash him. Might scare him from his coffin.”

If Jasmine’s narration provokes laughter in the reader, he or she becomes complicit in the cruelty. Before Semona is able to slip away, Dee runs after her and, with a jerk, tears the coat off her shoulders and exposes lines of deep pockets crammed full of meats, cheeses, “a whole loaf of bread, [and] even a whole bottle of ketchup.” Then, in front of the crowd she laughs uproariously and says, “Why, Miss Semona, I didn’t know you ran a grocery store out of your coat!” But the cruelty of the two young women escalates and results in a conclusion that is genuinely disturbing. I don’t wish to give away too much, but suffice it to say that, in the end, they discover that Semona’s eccentric ways are indeed driven by poverty. She steals food out of necessity.

The three tales I have touched on here are not necessarily the best of The Gift of Gab; they are merely representative of the scope of Ivey’s scope and sensibility. Virtually every story in this collection is a gem, told in a voice that is unique and enduring. Southern fiction, generally speaking, has seen better days than the present, but Ivey’s work is proof that the tradition is not yet moribund, not by a long shot.

Lastly, I would in closing offer praise to Green Altar Books for making this collection available, and to their talented designer Boo Jackson for one of the most arresting cover images I have seen in some time.

One Comment