There is nothing more scholastically problematic than attempts to draw comparisons between and/or among the figures of history. Such an effort can be considered even vaguely accurate only if and when the people being juxtaposed are of the same time period. In that case, at least, the circumstances surrounding them may be fairly equitable! But even that is not always true. As well as historical periods, locations make a profound difference for what existed in one individual’s country or region might have been entirely different for that of the other, thus making their actions understandably divergent. Even general circumstances such as war and peace affect those being compared and thus, affect any response they make to life circumstances. As a result, comparison between historical figures must be held to a rigorous standard involving the life experiences of each as well as the conditions under which they acted.

Even more to the point, the worldview of the individual making the comparison is clearly all-important. For the person who acts in a way that incurs the censure of that individual – even though the act may have been altogether legitimate under the circumstances – is sure to negatively influence any findings. On the other hand, the other figure may gain the sympathy and acclaim of the scholar involved, even if his actions were contrary to the best decision under the existing circumstances. The only time any action might be condemned out of hand is when the actor knows that it was wrong according to the existing standards of his day! For there is an unfortunate propensity in these days of the availability of endless amounts of information, for people to make judgments not according to the era under scrutiny, but according to the present “cultural standards.” When this is done, all such comparisons should be rejected out of hand as they have no legitimacy. It is not permitted to change the rules of the game after the game!

Now why, one might ask, is this a matter worthy of consideration? Simply because such comparisons do much more than pit the actions of one individual against those of another. Rather, such endeavors are usually an effort to “prove a point,” said point being addressed in accordance with the actions of those being compared that are then used to validate or invalidate that point. But that itself is sufficiently dangerous to make any comparison questionable at the very least. Once an academic has an “agenda,” his “audience” must be very careful regarding the development of any conclusions validating that agenda vis a vis its relationship to the acts of those being studied. More often than not, such reported behaviors almost inevitably lead to the academic’s desired conclusions! Indeed, this is often so, no matter how the facts have to be twisted, altered and/or ignored to produce that conclusion. For it is an academic of exceptional principles who will openly acknowledge when a much desired viewpoint cannot be validated or, worse, is actually debunked as a result of his labors.

Let us then look at one book whose title makes clear at least the historical figures being compared. The work is The Man Who Would Not Be Washington by Jonathan Horn. To make my point I do not reference the book itself – though I have purchased a copy – but rather, only the title that inspired me. In any event, the “man” in that title is Southern hero, Robert Edward Lee and the comparison being made as far as I can determine from the title alone, is Lee’s decision to “go with” his home state of Virginia at the time of the so-called “civil war” rather than Washington’s choice to embrace the cause of what was a gaggle of individual States no matter what was best for his home State, Virginia. Indeed, Lee was offered – and refused – at the time of the Civil War what Washington had also been offered and accepted at the time of the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, that is, command of the American forces to be used in the upcoming conflict.

For Washington, that amateur army would go on to fight the armies of Great Britain and its mercenaries in an effort by the thirteen individual colonies (later States) to gain their independence from the British Empire. For Lee, that command would have had him lead the far more seasoned armies of the now well-established United States against those formerly “sovereign States” that had either already withdrawn (seceded) from the Union formed by the Constitution or were in the process of doing so, one of which was Virginia, the home of both Washington and Lee! Now these circumstances may appear as relatively similar, thus making of Lee the man who “refused” to follow Washington, the man who had fought not for Virginia – or not for Virginia alone – but for the United States, considering the needs of Virginia secondary to the needs of the new nation being formed! If that indeed was the conclusion being put forth in the book so entitled, I believe that nothing could be further from the truth!

Let us begin by taking a brief look at the circumstances surrounding both men:

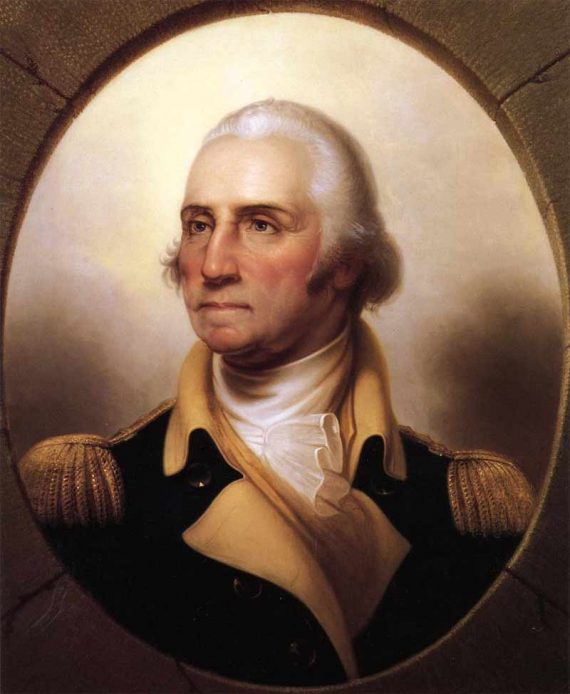

George Washington was born and grew up in the Royal colony of Virginia. In his youth, he considered himself an Englishman and a “Virginian,” only as that identity was related to living in that particular political and geographic location. Washington was the son of a second wife and therefore, upon the death of his father when he was very young, did not inherit any major estates. And so, as a young man, he chose to be a soldier, following in the footsteps of his beloved elder half-brother Lawrence. As an officer in the Virginia militia, he attempted to obtain a commission in the British army but was denied because he was “a colonial,” a matter considered by the British military as making him inherently inferior. And though he rose in both military fame and personal wealth, Washington never forgot the snub he received from the government of the King!

As the treatment by Britain of her American colonies grew ever more oppressive, Washington, who had by that time left the militia and returned to his farm, became ever more dissatisfied, realizing that the colonies could (and should!) govern themselves rather than being exploited economically by Britain. Parenthetically, it would seem that economic exploitation by Government played a role in both men’s actions. Furthermore, Britain forbade the people of its Atlantic colonies to “go west” and settle in the interior. This was a clear effort to keep the colonial population close to the coast thus permitting the British navy to land troops should there be any foolish notions of disobedience by the Americans. In response to the developing situation, Washington voted with the House of Burgesses to succor Boston after Britain placed a stranglehold on that city following the famous “Tea Party” and as a further testimony of his sentiments, he arrived at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia dressed in military garb and by doing so, clearly testified to Virginia’s willingness to fight for the rights of her fellow colonies. For it must be remembered that open warfare against Britain existed only in Massachusetts at the time! The Middle and Southern colonies had yet to hear a shot fired! As a result, New England members of the Continental Congress were concerned that they might not be supported by those same “peaceful” colonies and hence, Washington’s bold display promising military support.

At this time, Washington’s military association was limited. He was a wealthy planter whose service made him knowledgeable in that area but he was not directly serving in the militia although his judgement was sought by that colony on military matters and in fact, he activated Virginia’s militia after the occupation of Boston, knowing that Virginia also lay open to British ships of war and the troops they carried. At the Second Continental Congress, he was nominated and then chosen to be “Commander in Chief” of the “army” John Adam’s voted into existence on that very day, an “army” that consisted of the various militias from Massachusetts and other New England colonies then assembled at Cambridge. Thus, we have the unique circumstance of the creation of an army with only one member on its rolls – its Commander in Chief!

If Washington’s situation before and during the Revolution was unique, his circumstances after independence was historically in a class by itself! For “The United States” did not, as did Athena from the brow of Zeus, spring fully formed from the Continental Congress. Indeed, after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, most of Europe waited for the newly independent “Confederation” to destroy itself as each colony fought for its position in what was now being called the United States of America! In view of the political, economic and military chaos, members of the Continental Congress called for a convention to amend the Articles of Confederation, the document under which the Revolution had been fought. Of course, we know that though the convention claimed to be about “fixing the Articles,” it was in fact intended to produce a very different governing document – the United States Constitution. Meanwhile, however, this fact alone could have been seen by many Americans as treason to the newly independent “country.” But all knew that George Washington’s involvement would make legitimate whatever was actually going on! Had he not come out of retirement, what had begun with an incredible military victory would have died in blood and reconquest before the decade was out.

Finally, Washington was the only man that the entire “country” would accept as the new Chief Executive under the Constitution! They knew he had walked away from military power as well as rejecting being made a king or an emperor when these positions had been offered to him by a “grateful people.” Indeed, the people knew that he only wanted to go home to Mount Vernon, but he remained an active participant understanding as he did that had he walked away, all would have been lost. The man was also painfully aware that everything he did would define an office that had never before functioned in human society. He worked with all sides in hopes of using good will, good sense and the love of the country that had been so dearly created in order to actually govern!

Washington subjected the will and even the needs of the individual States – including Virginia! – to what he saw as best for the country as a whole, understanding that often states – like nations – can be blind to the common good and absorbed in their own problems even to their own detriment as well as the detriment of their fellow states. This was a very hard lesson he had learned during his years as Commander in Chief as his army was starved for food, arms, money and men because the colonies were more concerned with their own “needs” real or imagined than the needs of the army fighting to make them free! Nobody knew better than George Washington what it was going to take to make what had been created on July 4th, 1776, survive into the future and he spent his few remaining years yoked to the plough of independence for America and the needs and desires of the People and the Sovereign States.

Robert Edward Lee was born in the first decade of the 19th Century, less than ten years after the death of George Washington but the nation succored by his fellow Virginian had continued despite great trials – economic, political and military. The Napoleonic Wars engaged the powers of Europe in still further expensive and destructive contests and the United States once again found itself engaged with its former master, Great Britain in the War of 1812. However, by the time Lee reached the age at which Washington’s pursued his own life struggles, things were very different indeed. First, there was in fact a “standing army” belonging to the United States albeit it was not very large compared to such forces found in Europe. Still, Lee was educated at the military academy at West Point to become an officer in that army. Washington had learned “on the job,” so to speak, while Lee had received instructions in the ways and means of warfare then being practiced. Like Washington, he was a quick study and was one of the best and brightest in that institution graduating second in his class and receiving no demerits during the time he spent there, a testimony to both his moral and intellectual prowess.

Furthermore, the “new nation” was no longer a rank amateur in the art of war! The greatest change, however, was that the standards involved were relatively uniform throughout the country and though local militias still presented as the largest numbers of troops available in a crisis situation, Lee’s “standing army” provided the officers’ core of such forces in any national military action. In fact, the absolute chaos with which Washington dealt during the opening years of the Revolutionary War, was no longer extant. As a result, America was able to respond to a military threat efficiently and, more important, successfully.

Ongoing circumstances:

Returning to the immediate beginnings of the United States, much had also happened to derail Washington’s vision of the new nation, a circumstance that had begun as the nation itself began. As its first President, Washington attempted to guide the path of the infant Republic using, as noted, good will, good sense and the love of the country that had been so dearly bought with blood, sacrifice and suffering. He created the concept of a “cabinet” using men with the requisite knowledge in all matters pertaining to the workings of a nation to help guide him into making those decisions that would best serve that nation and its people. He was a man of informed compromise, seeking common ground even when and where little was to be found. Unfortunately, Washington was to learn to his sorrow and chagrin, that his own great virtues of honesty, integrity and disinterest* were not to be found – with very few exceptions – in those to whom he looked for assistance. In his address to the nation as he left the office of President, Washington warned against “the spirit of Party:”

I have already intimated to you the danger of parties in the State, with particular reference to the founding of them on geographical discriminations.** Let me now take a more comprehensive view, and warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the spirit of party generally.

This spirit, unfortunately, is inseparable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human mind. It exists under different shapes in all governments, more or less stifled, controlled, or repressed; but, in those of the popular form, it is seen in its greatest rankness, and is truly their worst enemy.

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.

Definitions (see above)

*Disinterest: the state of not being influenced by personal involvement in something; impartiality. A person who is “disinterested” looks upon a situation without being subject to personal desires or interests. He is able to seek the best solution rather than any personally desired one. This is the spirit in which at all times George Washington fulfilled his obligations to America.

**Here Washington speaks specifically of the already growing tendencies of the States to act according to their locations as was seen mostly in the North-South axis. Of course, we all know the end result of that sad situation in the next century.

Sadly, the spirit of party was already fixed as the United States began. Washington not only found that spirit causing dissension in his own cabinet as well as the federal government at large, but that it had gotten to the point at which those involved used the press to abuse him if he chose to support the beliefs and agendas of a man on the “other side” of the issues of the day. At that time, there were two parties in fact if not in name, those who supported the Constitution and its central government – the Federalists – and those who preferred most power to reside in the individual States vis a vis that government – the Republicans. The latter was despite the proof of the weakness of the doctrine of “States rights” at least as an ongoing guiding principle that had almost lost the Revolution, thus destroying the new nation that that war was fought to establish.

But that was only the beginning. By Lee’s time, quite another matter had arisen that also involved “States’ rights” along with the passions of party and, worse, that “root of all evil,” the love of money. For by 1860, there were now thirty three States along with ten organized territories that would become States in the future. The number of States had more than doubled but the issue of slavery continued to trouble the growing nation as it had during the Constitutional Convention. In 1820, Congress passed the Missouri Compromise, signed by then President James Monroe (a Virginian) admitting that State into the Union as a slave state and, as a balance, the State of Maine as a free state. The very understanding of the need to have such a balance was a powerful portent of what was to come. The law also banned slavery from the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands located north of the 36º 30’ parallel (the southern border of Missouri) thus isolating the region and people of the South to perpetual political subservience within the federal government. The Missouri Compromise would remain in force for just over thirty years before it was repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

But the real problem between the “slave” and “free” states was not slavery per se, but the economic contrast between the two sections. This situation was formally revealed in a message delivered to the Congress by Missouri Senator Thomas H. Benton in 1828, three decades before the Cotton States seceded from the union. Speaking on the floor of the Senate, Benton stated:

“Before the (American) revolution [the South] was the seat of wealth . . . Wealth has fled from the South, and settled in regions north of the Potomac: and this in the face of the fact, that the South, . . . has exported produce, since the Revolution, to the value of eight hundred millions of dollars; and the North has exported comparatively nothing. Such an export would indicate unparalleled wealth, but what is the fact? . . . Under Federal legislation, the exports of the South have been the basis of the Federal revenue . . . Virginia, the two Carolinas, and Georgia, may be said to defray three-fourths of the annual expense of supporting the Federal Government; and of this great sum, annually furnished by them, nothing or next to nothing is returned to them, in the shape of Government expenditures. That expenditure flows northwardly, in one uniform, uninterrupted, and perennial stream. This is the reason why wealth disappears from the South and rises up in the North. Federal legislation does all this!”

At the beginning of the Republic, it is claimed that America’s own Philosopher-Scientist-Diplomat, Benjamin Franklin said of the new government:

When the people find that they can vote themselves money, that will herald the end of the republic. Sell not liberty to purchase power.

But whether Franklin did or did not say that – and some do question it – as can be seen by Senator Benton’s testimony, many in government had learned to use the money raised by the federal government in ways never intended by either the Constitution or the men who created that same federal government. Certainly, Washington would not have permitted any such agendas! But this was nothing new! Actually, the war between Britain and America was not between governments, per se, so much as it was between the colonies and the East India Company, a massive corporate enterprise so bound up in the finances of the Empire that their interests became as one. In a smaller version of that same circumstance, young George Washington’s dealing with the French in the Ohio Valley was pushed by the colony’s Royal Governor, Dinwiddie to aggressive actions in support of the Ohio Company, another corporate enterprise but of considerably smaller size and influence. Everything about the conflicting claims in that area centered around money. Had there been no profit to be made, neither European nation would have wasted their time or their blood in the region!

And so, when the eternally smaller “South” could not prevent the horrendous tariffs that were to be imposed after the election of Abraham Lincoln, the so-called “Cotton States” decided to secede from that union formed by the Constitution. Of course, those States still remaining were very much determined that such a loss of revenues should not be permitted. Certainly, this was the position of the newly elected President! Today, it is the politically correct, “woke” version of history to claim that the war was waged to “free the slaves” though Northern states such as New Jersey that had retained slaves obviously were not subject to invasion. But this claim is made nonsense first by those slave States remaining in the Union not being forced to emancipate their slaves and secondly by the offering of the original 13th Amendment to the Constitution. Named the Corwin Amendment after Pennsylvania legislator Thomas Corwin who presented it, this Amendment placed slavery directly into the Constitution, not as a matter of “understanding” but in name and in perpetuity with caveats preventing the federal government from attempting its removal! By that time, however, the Cotton States had decided that they had been victims of the rest of their “brethren” for far too long and wanted, as Confederate President Jefferson Davis stated, “. . .only to be left alone.” The upper South including Virginia, had not yet seceded but upon being pressed to supply troops for the federal government’s invasion to subdue their fellow Southrons, they then followed the Cotton States out of the union.

When these States began to threaten secession, then President James Buchanan requested of his Attorney General Judge Jeremiah Black to find him a constitutional means by which to either keep those States in the Union or, if they seceded, to legitimately force them back. On November 17th, 1860, the President wrote to Judge Black on the specifics of the matter:

SIR, The excitement in the Southern States caused by the recent presidential election and by the previous expressions in the North of hostility to Southern people and their domestic institutions may produce in some places resistance to the laws of the Union. As I desire to be guided in this emergency solely by the Constitution, and as there are several important points obscure enough to need some exposition, I have to require your opinion in writing on the following questions:

- In case of a conflict between the authorities of any State and those of the United States, can there be any doubt that the laws of the Federal Government, if constitutionally passed, are supreme?

- What is the extent of my official power to collect the duties on imports at a port where the revenue laws are resisted by a force which drives the collector from the custom house?

- What right have I to defend the public property (for instance, a fort, arsenal and navy yard), in case it should be assaulted?

- What are the legal means at my disposal for executing those laws of the United States which are usually administered through the courts and their officers?

- Can a military force be used for any purpose whatever under the Acts of 1795 and 1807, within the limits of a State where there are no Judges, marshal or other civil officers?

I will thank you to give this subject your early attention and let me have your opinion without loss of time.”

As can be seen, Buchanan wanted very specific answers with regard to his constitutional rights and duties as President to deal with the matter he rightly believed about to come to pass. Black’s response is available to be read in full – and it should be, especially by those whose understanding of the origins of the so-called “Civil War” are based on Northern propaganda. But as to the man’s response to the President sans legal references, Black’s arguments can be summed up as follows:

- The president must not overstep the limits of his legal and just authority.

- The operations of any military force must be purely defensive.

- To send a military force into any State to act against the people would be to make war upon them. (See the definition of treason below in Article III, Section 3, United States Constitution – vhp)

- The laws put the Federal Government strictly on the defensive, and force can be used only to repel an assault on public property.

- In the event of the secession of any state, the president must execute the laws to the extent of the defensive means.

- The Constitution does not give Congress the right to make war against any State or to require the president to carry it on except when the State applies for assistance against her own people or to repel an invasion of a State by enemies from abroad, not to plunge them into civil war.

- A declaration of war or hostilities by the Central Government against any State or states would absolve all the States from their Federal obligations.

- The General Government may not engage in a war to punish the people for the political misdeeds of their State Governments or to force them to acknowledge the supremacy of the central Government. Some conquering others and holding them as “subjugated provinces” would destroy the theory upon which they were united.

- The arming of any portion of the people against another save for “protecting the General Government in the exercise of its constitutional functions” would constitute an end of the Union.

The final argument against the legitimacy of the federal government “declaring war” on the States that seceded in 1860 under the argument that secession was “illegal,” is absolute. During the ratification process of the Constitution, three states – New York, Rhode Island and Virginia – placed into their ratification documents the right of those States to leave the union then being created under particular, defined circumstances. When votes were taken regarding the ratification documents of all the States, those three were accepted without any attempt to remove those caveats. In any compact or contract – as was the Constitution! – all signatories have the same rights! Therefore, the right to secede put into that document by New York, Rhode Island and Virginia could also be claimed by the remaining signatories, as well! This is why no charges of treason were ever leveled against anyone in the South after the Civil War, that is, because secession was completely constitutional. Below is the secession wording found in Virginia’s ratification documents:

We the Delegates of the people of Virginia, duly elected in pursuance of a recommendation from the General Assembly, and now met in Convention, having fully and freely investigated and discussed the proceedings of the Federal Convention, and being prepared as well as the most mature deliberation hath enabled us, to decide thereon, do in the name and in behalf of the people of Virginia, declare and make known that the powers granted under the Constitution, being derived from the people of the United States may be resumed by them whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression, and that every power not granted thereby remains with them and at their will: that therefore no right of any denomination, can be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified, by the Congress, by the Senate or House of Representatives acting in any capacity, by the President or any department or officer of the United States, except in those instances in which power is given by the Constitution for those purposes: and that among other essential rights, the liberty of conscience and of the press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified by any authority of the United States.

There can be no doubt that once this document was accepted as a legal ratification of the Constitution, the right of the State of Virginia and any and all other signatory States to secede became absolutely legal and constitutional. On the other hand, the response of the federal government in sending troops into the Southern States was in fact treasonous according to Article III, Section 3 of that document:

“Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them (the States), or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.”

The Federal Government had no constitutional right to declare war on any State as pointed out by Judge Black, especially as that State was acting in accordance with its rights under the Constitution. Much is made in this matter of Washington’s response to the Whiskey Rebellion, but it must be remembered that he acted at the request of the government of Pennsylvania (a State!) and to prevent the ongoing lawlessness that had plagued the former colonies before the adoption of the Constitution and the establishment of an actual working government! There were means by which citizens could present grievances, but open revolution was no longer acceptable! Washington went with his troops and confronted those in revolt, at which point, they all went home without firing a shot in respect for the man who had led them to freedom. The “organizers” were captured, tried and sentenced to death, but Washington again intervened and pardoned them, using his power to apply mercy to men whose actions were those of people long bereft of the good government he was trying to establish.

So now, let us look at the situation in the case of both men when offered the command of their “nation’s” military as it existed at the time:

First: Who was the enemy?

For Washington, it was Great Britain. Thirteen disparate colonies were going (or were supposed to be going) to work together to remove the yoke of the British Empire and permit those thirteen colonies to become independent. At the time, they really weren’t sure how that “independence” would play out or even what it meant! So far, each of the colonies had functioned separately. They all lacked independence but as Britain became successively more tyrannous as time went by and as new generations were born and grew up absent the direct involvement of Parliament and the King, having such strictures placed upon them created sufficient resentment to lead to the outbreak of a revolution or rebellion, the designation of which depended upon which side you were on.

So, Washington’s enemy was a force outside of America, a force that had made clear to him that he was not worthy to hold a commission in the British army, nor was he legally permitted to keep his own money but was forced, as the rest of his fellow Americans, to pay far too much to Britain for far too little in return. Therefore, it was not difficult for George Washington to see the King and Parliament as tyrants and worthy of being removed from their position of power over himself and the American people!

For Lee, there was no true enemy. He rejected secession but he also knew that the use of the federal military to force upon sovereign States the desires of the federal government against their stated will was totally foreign to the concept of America certainly as George Washington knew it! He realized that the Sovereign States in order to be “sovereign” as defined in the Constitution could not be physically coerced against any action identified as “legal” – such as secession. Like it or not, nobody could be arrested for demanding that his State secede from the federal union. Such was not the case for those in Washington’s day! Those who demanded freedom from the yoke of Great Britain spoke treason!! For Lee, treason would have resulted had he taken command of federal troops preparing to wage war against those States that had left the Union. Even the matter of Fort Sumter and all that that involved would not have lessened the charge against him for everything that happened prior to the opening of the “Civil War” involved unconstitutional actions by the federal government and those who “aided and abetted” its agenda of compelling the Cotton States back into the union by military force, if necessary.

Second: Was treason committed and, if so, who committed it and what were its consequences?

As noted above, the very act by Americans against the British whether in word or deed was, in fact, legally treasonous. Of that there can be no doubt. Furthermore, to act upon any effort to force Great Britain out of the colonies by the sword and to respond to their military with force – especially as did Washington, the “Sword of the Revolution!” – made one a “rebel” and guilty of high treason, the punishment of which was to being hanged, drawn and quartered, a medieval horror that remained on the books in Britain until it was abolished by the Forfeiture Act of 1870! Few realize even today that Washington’s actions would have had such dire consequences for the man had he fallen alive into British hands! Of course, he knew – a matter that should further increase our appreciation of his courage and willingness to sacrifice everything for the cause!

For Lee, true treason would have resulted had he taken command as Lincoln wanted, of the federal army. Of course, in both instances one must take into account that old saying, “if you win, it isn’t treason!” Washington won and his head wasn’t put on a pike and displayed on Tower bridge nor his “private parts” and bowels cut out and burned before his still living eyes nor his arms and legs cut off and preserved to be disposed of at the wishes of the King! There was treason, but the consequences involved never came to pass for obvious reasons!

Lee, however, evaded any possible legitimate charge of treason by refusing to lead an army in an attack on the Sovereign States of the South but, rather, he took up arms in Virginia’s defense – something that was not treason! Of course, as often happens when the wrong side wins, there was talk of charging Lee with treason – a sort of inverted injustice! – but in the end it was decided that nothing would be gained by spilling more blood than had already been spilled in our poor nation’s most sanguine and unjust war. And besides, a lengthy trial might well have educated Americans that they had been hoodwinked into committing treason by their own government.

Conclusion:

In his actions in the “Civil War” Robert E. Lee did in fact act as did George Washington in that he fought to prevent a tyrant from despoiling and enslaving not only his beloved Virginia, but all of the Sovereign States that had once been a part of that government for which George Washington fought both militarily and politically. For it is most important to remember that the federal government’s victory over the South destroyed the rights of all the sovereign States, not just those of the South! What had changed was not the behavior of the hero soldiers involved, but the nature of the enemy. The government that Washington had worked and slaved to bring into being in the hopes of providing a true republic, had, over time, gone the way of party and greed and dishonesty and all of the evils that both men rejected to the death. No matter what name one gives to tyranny, these two moral giants resisted it with every fiber of their being and that makes of them heroes to anyone who understands the nature of heroism.

Post Scriptum: If, perchance, author Horn’s work does not address the comparison made above, I ask his forgiveness for my misunderstanding. Yet, book titles are important. Authors hope to draw readers by providing titles that pique interests and/or challenge beliefs. Certainly, the gentleman’s title did so on my part at least! For myself, it was simply too good not to use as a fulcrum upon which to make the arguments that I have attempted to make. Remember, things are not always what they originally seem and many things that are obvious at first glance are far more complex upon investigation!

The US military officer’s oath of office was constant from 1830 until 1862. The 1830 oath had the officer swear allegiance to the United States and to defend THEM from THEIR enemies. For some reason (sarcasm implied), the US decided to change the oath in 1862 to support and defend THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES. Why was this change necessary if all understood the previous oath as an oath to the nation and not the individual State? You are correct; it was not treason for the States or for the officers to leave the union.

I believe that I mentioned that the defeat of the Confederacy was the defeat of the sovereignty of ALL the “sovereign” States and a placement of the federal (central) government into a position never designed for it under the Constitution. Washington knew that. He was very careful to keep that government in the position for which it was designed ~ that is, to allow the United STATES to function as a single entity without each PERSON (never mind State!) losing their sovereignty. If Lee WAS Washington, Lincoln was not.

Lincoln was a railroad lawyer who awarded railroads a land mass equivalent to the area of the State of TEXAS. If he had been born a century later, he would have lobbied for NAFTA, GATT and WTO…he would have gutted the middle class for his friends. Lincoln was just another fraud in too long a line of politicians who betrayed their constituents.

The question never asked is: What if Lee had accepted the offer to command the federal/yankee armies? Why would he have done so? For money, fame, power? No. He would have taken the job if his oath had been to the United States. But then again, the States would not have been able to claim sovereignty as their understanding would have been the same as General Lee’s. Without the officer corps, there would have been no Southern Army; without the belief in the sovereignty of the individual States, there would have been no war. All would have understood the submission of the States to the Federal government.

It is said the question was settled by force. Questions settled by force lend themselves to dispute.

Truth is spreading. You are part of this movement. Thank you for your efforts.

“the defeat of the Confederacy was the defeat of the sovereignty of ALL the “sovereign” States”- that is why I refer to Lincoln’s war as the War Against the States.

You must remember that the scenario I believed (haven’t read the book, so I can only go by the title!) is that by failing to defend “the United States” as did Washington, Lee went with his State rather than his nation. My point was that Lee refused to commit treason as Lincoln was going to do by waging illegal war against the seceded States (see the definition of treason) even though he was very much against secession. He was an American first rather than a Virginian (as Washington became as the matter developed with Great Britain), but he realized that the people now running the “federal government” were not acting in the spirit of the Constitution. I have a long article on Lincoln and the Constitution that proves to save “the government” as he put it (NOT the nation!), he was willing to remove the Constitution until the “Union” had been restored.

I made the effort to read reviews of The Man Who Would Not Be Washington. I’ve heard of the book but don’t need to read it. I’ve already read Nolan, Fuller, Guelzo, Brown, Connally, etc.. They’re all the same – varying polemics with the same purpose. Similarly, reviews feature portrayals of RE Lee as “tortured”, “complex”, “an enigma” and “intriguing”. Casual familiarity with Lee shows him as modest and reserved but entirely self-aware and sure of himself and the decisions he had to make. Anguish caused by the secession of Virginia was real but there was never a moment of doubt of the course he would take, nor was there ever any regret around his actions during or after the War. Most certain is, even with the allegiance to the memory of Washington, General Lee never attempted to live up to any standard but his duty to God, Virginia and his family.

Mrs. Protopapas, I somehow just discovered this site and was happily surprised to see that you’ve written about John S. Mosby. I don’t know how I’ve missed it from always being on the lookout for new books for the Confederate library. I’ve been to the usual places and wondered if it is available in hardcover. I’d just decided that next up would be to reread VC Jones’ or Ramage’s Mosby but intend to find a copy of yours. Paperback will be fine if it’s all that’s available. Can you advise?

My book is now available through Shotwell Publishers under the title Col. John Singleton Mosby In the News: 1862-1916. The original title was A Thousand Points of Truth: the History and Humanity of Col. John Singleton Mosby in Newsprint. I believe it can still be purchased at Amazon and certainly through Shotwell itself. The newer book has some added information not available at the time of the first edition. I don’t know if it is available in paperback. It is a book that presents a great deal of information on man simply not found in other works on him.

As for Lee, I knew it would compare him unfavorably to Washington, but I understood how that scenario would play out. Believe me, those same folks who excoriate Lee do so to Washington because he owned slaves. Really?? Didn’t King David also and a lot of other “heroes” of history.

I’ve ordered Col. John Singleton Mosby In the News: 1862-1916. Evidently, it’s not available in hardcover. It’s okay – it won’t look as pretty on the shelf after I read it so maybe I’ll have to place the Mosby miniature die cast in front to disguise it.

JS Mosby was my first favorite Confederate as a kid, back when all I cared about was baseball. After learning and understanding about his post war crankiness I admired him no less. As with his comment, “As far as I know the War was about nothing but slavery”, it caused me to study deeper the whole messy business of the War, politics and provocations, conditions and context.

I’m looking forward to the book. Thanks.

My love for Mosby is that for Washington. Both were exceptionally honest and brave men. When asked by a friend about whom to believe in a particular dispute, Mosby or the other party, Mosby told his friend to “take sides with the truth” rather than either party. That is how Mosby thought and that is how Washington thought. The problem is that such men are ultimately betrayed and deeply hurt by those whom they most trust. It happened to Mosby and it happened to Washington.

…..For it is most important to remember that the federal government’s victory over the South destroyed the rights of all the sovereign States, not just those of the South!……. just curious, did the did the northern states still invoke states rights at this point because they knew they had the federal govt power solely in thier pocket now? ie, with all the voting restrictions put on white southern voters in the decade after the war?

They had bought into the “Union” argument and believing themselves “part and defenders of the Union” did not see that they had lost anything during the war except their sons, fathers and brothers. However, YEARS later during a federal power grab, one State official cried out during a congressional hearing, “What ever happened to States’ Rights?!” The States that fought against the Confederacy did eventually learn that they too had been conquered, but it took them a while.

Lincoln’s Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon Chase crowed that “states’ rights died at Appomattox” but the victors saw only what they wanted to see. I hear people to this very day proclaiming, The South was right! as if they’re the first to notice.

They are, indeed, slow on the uptake.

Probably why THE SOUTH WAS RIGHT (Kennedys) is a best seller.

Yep. A great piece of work. I have a loaner copy – I’m funny about my books leaving home.

I hope future editions continue as a source of information and not a chronicle of decline.

was it continued flooding from bolsheviks, possibly jews, and continued socialist leaning immigrants that too overan even the northern state small r republicans left, post WBTS? it seems like i had read a portion of a book somewhere that post war, especially by the 1920s many more socialist leaning 1 or 2 gen individuals had made their way into the academies.

Sadly, by the time of the Civil War, all of America had become New England except the South and New England despised everybody but themselves. In Washington Irving’s story about the headless horseman, Ichabod Crane was the ultimate Yankee, despising the locals and believing himself utterly superior to everyone. That’s the spirit that existed in the rest of the US outside of Dixie before the ACW.