In my April account of the British territory of Bermuda and its intimate relationship with both the South and the Confederacy, I had omitted one important factor . . . Bermuda’s role concerning the great seal of the Confederate States of America. The unusual history of the seal was so complex that I certainly felt the story merited its own telling.

A week after the successive secession of South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas between December 20, 1860, and February 1st of the next year, a provisional Confederate government was formed in Montgomery, Alabama. As it was with the creation of the United States eight decades before, there was to be much debate by the new government in relation to such vital matters as a proper constitution, as well as a national flag and seal.

Within a month, a national flag, the seven-star “Stars and Bars,” had been adopted and a week later, the Confederate Constitution had been unanimously ratified by the seven states . . . a document, while patterned after the Constitution of the United States, was one that reestablished emphasis on state’s rights and sovereignty. It also made several major changes in the Article to establish an Executive Branch, such as a single, six-year term for the office of president and another that gave the president the power of a line-item veto. The new nation’s seal, however, was quite a different matter.

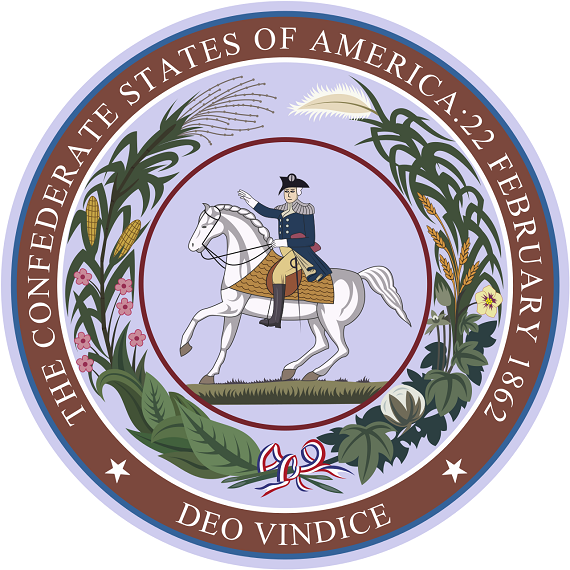

For the next two years, the Committee on the Flag and Seal chaired by Representative William Miles of South Carolina debated the design of the seal. On April 4, 1863, the Committee finally approved the seal’s design for an equestrian statue of George Washington surrounded by a wreath made up of the South’s major agricultural products . . . cotton, rice, sugar and tobacco. The date February 22, 1862, was added to mark President Davis’ inauguration in Richmond, as well as the Latin motto “Deo Vindice” (under the protection of God).

Using Richmond’s famous statue of Washington by Thomas Crawford and Randolph Rogers as his model, a rendering of the seal’s design was composed by Irish-born sculptor John Foley. A month later, Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin sent Foley’s drawing and the seal’s proposed measurements to the Confederacy’s envoy in Great Britain, James M. Mason, with instructions to have the seal cast in silver. It took Mason until April of the following year to locate the right person for the commission, Joseph S. Wyon, the chief engraver for Queen Victoria’s official seals.

The three-pound seal was completed in June of 1864 and with it, Wyon included an ivory handle and a mechanical screw press, as well as a large supply of such sealing materials as red wax, parchment paper disks and silk cord. The items were delivered to Mason in three, tin-lined crates at a total cost of about $700 . . . which would amount to more than $13,000 today.

In July, Mason entrusted the shipment of the items to Confederate Navy Lieutenant Robert Chapman. Chapman and several other Southern Navy officers were in London following the sinking of the “CSS Alabama” in its engagement with the “USS Kearsarge” off the coast of France the month before. To avoid capture, Chapman first loaded the three crates aboard the Cunard steamer “Africa” that had recently resumed sailing from Liverpool to Halifax, Nova Scotia.

After his arrival in Halifax, Lt. Chapman then loaded the items on another Cunard steamer, the newly-built “Alpha,” and headed for St. George’s in Bermuda. In Bermuda, Chapman then boarded the blockade runner “Hawk,” a very fast vessel that had been built as a British warship, and on the first of September began the final, seven hundred mile leg of his journey to Wilmington, North Carolina. He took with him only the seal and its ivory handle in a leather satchel, with the press and all the other items remaining in Bermuda.

The seal was then transported to Richmond and presented to Secretary Benjamin on September 4th. However, as the press had remained in Bermuda, the seal could not be properly used and from the time of its final delivery until the end of the war, it was used only twice on official documents. For all other documents, Benjamin continued to use the seal that had been created for the provisional government in Montgomery, one that displayed only a scroll of paper and the words “Constitution” and “Liberty.” That seal is now resting somewhere at the bottom of the Savannah River where Benjamin threw it on his flight to England after the war.

As to the use of the great seal, on the day he received it, Secretary Benjamin managed to employ the seal on the authorization of a set of War Department documents. The documents pertained mainly to the creation of a twenty-man company of troops to be led by Lieutenant Bennett Young of Kentucky in behind-the-lines operations. On October 19, 1864, the group ultimately carried out the raid on St. Albans, Vermont. While the documents clearly made the raid an official action of the Confederate Army, it is now improperly considered an act of Southern terrorism.

The only other known use of the great seal took place on February 7th of the following year. This was on a document appointing Major General John C. Breckinridge as the Confederacy’s fifth Secretary of War. Prior to the war, Breckinridge had been the U. S. vice-president under President James Buchanan, had represented Kentucky in both houses of the U. S. Congress and had been one of the three Democratic presidential candidates in the election of 1860. His appointment was signed by both President Davis and Secretary Benjamin, and had remained buried in the U. S. National Archives until its discovery in 1995.

The fate of the great seal itself remained a mystery for almost half a century. In 1912, however, it was learned that the seal had been included in one of the ten cartons of State Department documents put together by a departmental clerk, William Bromwell, during the government’s evacuation of Richmond in April of 1865. The boxes were ultimately stored by Bromwell at the courthouse in Charlotte, North Carolina.

A year later, when Bromwell moved to Washington, D. C., and went into practice with the law firm of John T. Pickett, he brought with him the documents and the seal. In 1868, he and Pickett offered to sell the documents to the U. S. government for a half a million dollars. Secretary of State Seward doubted the authenticity of the material, as well as balking at the price, and negotiations dragged on until 1871, when Congress finally approved purchasing the items for $75,000.

Fearing that the government might merely confiscate the documents without payment, Bromwell and Pickett claimed they were stored in Hamilton, Canada. When Navy Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge was appointed by the State Department to inspect the documents, the boxes were secretly sent by rail to Hamilton and after their approval there by Selfridge, were returned to Washington and the $75,000 was paid. No mention of the seal had been made, however, and during the return trip from Canada, Pickett, for some reason, gave the seal to Selfridge. Two years later, Pickett borrowed the seal to produce a thousand electrotype replicas coated in gold, silver and bronze which he professed were to be sold to aid Confederate war widows and orphans. He then returned the seal to Selfridge.

All of these details came to light when, in 1912, the head of the Manuscript Division in the Library of Congress, Gaillard Hunt, had followed a trail of clues that led him to the involvement of Bromwell, Pickett and Selfridge. As Bromwell and Pickett were both deceased, Hunt threatened Selfridge with exposure, and the latter offered to sell the seal to Hunt for $3,000. With the help of one of George Washington’s descendants, Hunt had the seal authenticated by the Wyon studio in London and arranged its sale to three prominent Virginians in Richmond, Thomas Bryan, Eppa Hunton and William White.

During his investigation, Hunt had also met Susan Harrison of the Confederate Memorial Literary Society when she was researching manuscripts at the Library of Congress. In April of 1912, Hunt contacted Miss Harrison with the hope that the Society might take custody of the seal. After several months of negotiation between the Society and the three men in Richmond, the seal and all the pertinent documents connected with it were presented to the Society in October of 1913. The seal was then put on display at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond which was at that time housed in the Confederate White House and it still remains in the present museum.

Over half a century later, the seal was once again used for an official function. In 1970, its owners, the Confederate Memorial Literary Society, created both the “Jefferson Davis” and “Founders “ awards to be presented to outstanding scholars in Southern history. A modern version of the Wyon press was also made to imprint the seal on the award citations.

As to the original Wyon screw press, that device remained in Bermuda in the hands of John Tory Bourne, the local merchant who had acted as the Confederate commercial agent in St. George’s during the war. When Bourne died in 1867, his belongings, including the press, were auctioned off and the device remained undiscovered until 1888 when the press and some of the original documents concerning the seal were found and purchased by John S. Darrell, a Bermuda shipping agent in Hamilton.

Using the design of the original seal, Darrell had a brass duplicate made in London by the Wyon engravers. Both the press and the replica of the seal remain in the private collection of Darrell’s descendants. In 1959, an authentic Victorian screw press similar to the Wyon device and another replica of the original seal were purchased by the Bermuda National Trust and put on display at the the Confederate Museum in St. George’s. There, imprints of the seal are now made on aluminum foil and sold as souvenirs.

As a final note, one of the early characters in the saga of the great seal also played an important role in the creation of another famous symbol of the Confederacy. The chairman of the provisional government’s Committee on the Flag and Seal, William Miles, had also been an aide-de-camp to General Beauregard at the first battle of Manassas. During that engagement, Beauregard noted that at a distance and in the smoke of battle, the new national flag was all too often mistaken for the banner of the invading Union Army. He discussed the problem with Miles and suggested that a completely different battle flag also be adopted. Miles said that the design for a national flag he had proposed might be used . . . one composed of a red field with diagonal blue stripes and seven white stars.

Miles’ design was finally approved and on November 26, 1861, it was made the official battle flag of General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Four additional stars had to be added for Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia that were then part of Confederacy, as well a two others for Kentucky and Missouri that had seceded in 1861 but were prevented by force of arms from leaving the Union.

The thirteen-star Confederate Battle Flag has since become one of the most revered emblems of the South, as well as the one most reviled by detractors of both the Confederacy and the South in general. The Battle Flag also became the symbol for many post-war Southern organizations such as the United Confederate Veterans, the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of Confederate Veterans, as well as the canton for the two subsequent national flags of the Confederacy, the “Stainless Banner” in 1863 and the final “Blood Stained Banner” two years later.

It should also be noted that at the end of World War Two, while the Stars and Stripes had been raised over Mount Suribachi on Japan’s island of Iwo Jima in February of 1945, it was the Confederate Battle Flag that was first hoisted over the last Japanese bastion at Shuri Castle in Okinawa three months later.

Thank you for following up! It makes my efforts to safely get two pieces of embossed foil back on the flight from Hamilton, without squashing them, worthwhile. Both subsequently safely framed, one for my office and one, a gift for a Washington & Lee law graduate who hasn’t turned against history.

Thank you for this most interesting and complete history of the seal. I’ve printed it for my future use and look forward to getting a souvenir from St. George on my next visit to Bermuda.