Created by the fiscal 2021 national defense authorization act, the Naming Commission’s duties included recommending procedures for renaming Department of Defense assets “to prevent commemoration of the Confederate States of America or any person who served voluntarily” with them. While nine U.S. Army posts named for Confederates have received the most attention, the commission’s “remit” extends much further. In fact, a logical end point to its (Diversity-Equity-Inclusion-inspired) work is nowhere to be found:

The Commission recognizes that [defense] assets commemorating the Confederacy or an individual who voluntarily served with the Confederacy will continue to be identified after the submission of the Commission plan. The Commission recommends the base rename, remove, or modify any such assets identified in the future [emphasis added].

The ramifications of the above remain to be seen, but already the U.S. Military Academy at West Point is undergoing a shameful transformation: its “Reconciliation Plaza” has begun to be dismantled, and will soon be altered beyond recognition. The plaza, consisting of stone “markers” arranged on the academy’s grounds, was presented by the West Point Class of 1961 on the occasion of their fortieth reunion in 2001. Exactly a century prior to the 1961 members of the Long Gray Line, the school graduated two classes in 1861 – one in May, the other in June. Graduates served in both the Northern and Southern armies.

The precise purpose of Reconciliation Plaza was to “commemorate the reconciliation between North and South and dedicate this memorial to our classmates who died in service to our nation” [emphasis added]. The latter intent was traditional at military schools (including my alma mater, the Virginia Military Institute), and was non-controversial.

Not so the former. The markers, duly noted by the Commission, depicted “acts and events between 1861 and 1913 to serve as examples of reconciliation.” But given the atmosphere in official Washington since the fruitless extremism-in-the-ranks hunt in 2021, such a purpose is suspect, especially if white men were behind it.

At least three markers or exhibits described by the Commission deserve particular attention. They depicted the following acts or events:

“Marker 4 portrays a Confederate soldier providing water to a U.S. Soldier wounded by Confederate guns”; and,

“Marker 6 commemorates Confederate [Major General] Stephen Ramseur and two U.S. Army classmates from West Point who comforted him as he lay dying after a surprise attack by Ramseur’s army failed.”

Stephen Dodson Ramseur, who had sustained multiple wounds in battle prior to the October 1864 Battle of Cedar Creek – and, at 27, was the youngest West Point graduate to be promoted to major general – had just had his second horse shot from under him when he was hit in the lungs, a mortal wounding. Learning of his condition and subsequent capture by Union forces, several of Ramseur’s friends from West Point “came to his side,” among them his close friend, George Armstrong Custer. Ramseur, whose first wedding anniversary was days away, had just learned of the birth of his daughter.

Astoundingly, the Commission found the depiction of these acts to be within its remit and unacceptable to remain in place. Indeed, at West Point’s Reconciliation Plaza. What Purity-Tested entity determines the giving of water to a wounded soldier, and the comforting of a dying soldier by his friends, to be unacceptable depictions of reconciliation – particularly among the very soldiers who fought one another honorably on the field of battle? If the actual participants themselves were able to reconcile to such a degree during or immediately after the heat of battle, who in a later generation dares to dismiss and hold in contempt such acts of kindness?

Commemorate is but the latest politically weaponized entry in the lexicon of those who “love all words that devour.” In the 2021 defense act’s four main, relevant paragraphs in Section 370, some form of the word “commemorate” appears in each – and is prohibitive of the Confederacy and Confederates. Without debating the merits, and mostly demerits, of Congress’s mandate, it is enough to return to the Commission’s own words. The primary purpose of the Class of 1961’s gift to West Point was to “commemorate the reconciliation between North and South,” which the Commission quoted [emphasis added].

The Commission may have wished otherwise, but commemorating the Confederacy or Confederates was not within the Class of 1961’s stated purpose. The Commission’s accurate quotation of the purpose in its report is at odds with – and severely undermines – its own recommendations.

Eight decades ago, the United States fought Germany and Japan in a costly, four-year war. Today, both former adversaries are among our closest allies. Sixteen decades ago, the United States fought the Confederate States of America in an earlier, costly, four-year war. By the 1940s, North and South had been reconciled. Ironically, today that reconciliation is being undone by those who presume to have the national interest at heart.

Will this Commission’s Reconciliation Plaza recommendation represent the philosophy or principles to be taught to cadets soon to be commissioned as second lieutenants in the United States Army? At storied West Point? Such an intentional position is at once surreal, outrageous, and yet another stark reminder of the thin veneer of civilization threatened by those whose leaders follow – wittingly or otherwise – in the path of the brilliant Italian political strategist, Antonio Gramsci, who in the 1920s and 30s foresaw cultural marxism as a potential game-changer in the West.

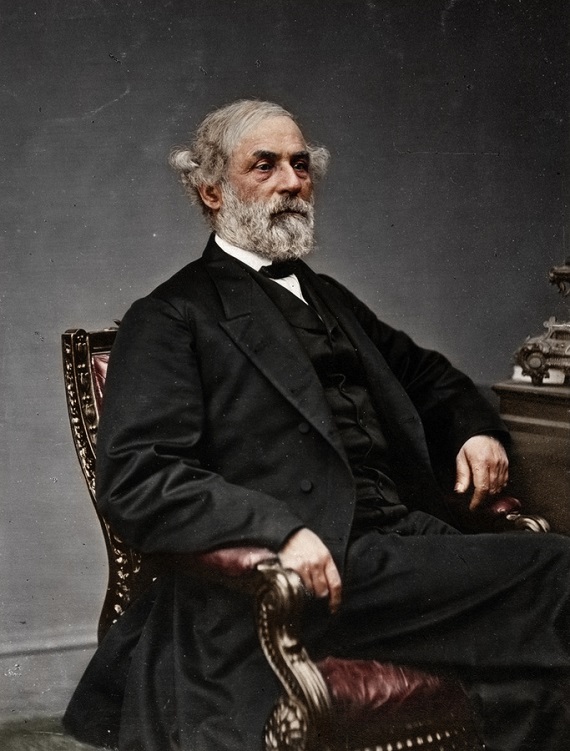

Returning to West Point’s Reconciliation Plaza, the third section to note is one of the best known, featuring the Grant and Lee busts situated on either side of Marker 8. The naming commissars made clear their preference is for General Lee’s bust to be removed – doing so, as always, in a dignified manner.

I can still recall a conversation from when I was a boy growing up in Maryland, fifty years ago. My father and his first cousin were discussing some aspect of the war. One was a native Alabamian and well-known nuclear physicist, the other an East Tennessean with deep roots in the region and even deeper knowledge of the area’s participation in the war. They commented within my hearing on a fact once widely known, that in the spring of 1865 Lee had refused to counsel his men to quietly disperse from the army in order to continue the fight, practicing what we call guerrilla warfare today. Instead, he instructed them to stay in ranks to the bitter end, and when the time came to return to their homes and farms, and to do their best to rebuild their lives, without bitterness toward their aggressors.

Years after that conversation, I encountered a remarkable passage in a book that discussed Lee’s tenure after the war as the president of Washington College, today’s Washington and Lee University. A professor at the school was known for speaking disparagingly of General Grant. One day, in Lee’s presence, the professor did as he was accustomed. Lee turned to him and said these words, which I wrote down on a card and kept in my wallet: “Sir, if you ever again presume to speak disrespectfully of General Grant in my presence, either you or I will sever his connection with this university.”

If only the Naming Commission could accept that General Lee was one of the two men who did the most to begin the process of reconciliation between North and South. The other, of course, was General Grant, by his magnanimity at Appomattox. But that would require the ability to recognize what authentic reconciliation looks like – which those who either are confused by mystical words like diversity and equity, or who actually seek to divide a society by its various superficial identities for their own purposes, refuse to accept.

Outstanding I wish it could be read and appreciated by all of young southerners who are being so misled by today’s outlandish misinformation!!

Erasure of US history. Good job comrade Bo.

The naming of a number of military installations, ships, highways, etc. for Southern officers and heroes was among a number of actions taken by Congress and other organizations and individuals to “bury the hatchet “ and end the intense regional animosity that remained after the War and so-called Reconstruction. Well, these woke anti-Southern cultural marxists have dug up the hatchet. I retired a full colonel from the US Army, but if any of my grandchildren expressed interest in joining any branch of the US military I would discourage them in no uncertain terms.