Going back to Jefferson, you can say that Jefferson’s vision of radical Federalism was of a libertarian Federalism, based on the rights of local self-government circumscribing and limiting their agent, the Federal government, whose referent is not a single people, but the peoples of the various States. It’s strange that in the writings from the Founding period, the plural of “people” is seldom, if ever, used. This is one of the difficulties of using the English language, because to use the plural of people, you really have to know what you’re talking about. It’s kind of like using the plural of “sand,” it sounds rather strange. So, these guys didn’t use “peoples” as we sometimes do to make the point clearer, as in “the peoples of the several States,” but they clearly weren’t describing a single people. Jefferson said: “The United States is a nation for special purposes only.” It’s a very clear statement. As you know, in Jefferson’s thought, the Natural Rights of Man represent the supreme political end for which governments have been legitimately constituted among men. By the same token, one might think that Federalism should be nothing more than the form of government best-suited to achieve a vital political end of paramount importance: The freedom of individuals to enjoy their own natural rights. This, however, is not the case. The self-government of the States and their supremacy over the Federal government have a peculiar and highly distinctive status in Jeffersonian thought, so much so that Federalism can in no way be relegated to the role of a simple means for achieving an end, even if it is the supreme political goal of individual freedom. The federal division of powers is not one of the possible ways designed to obtain the goal of liberty; rather, it is an end in itself. States’ Rights became the Rubicon of Jeffersonian republicanism. The most important thing was that the United States remain “a nation for special purposes only,” or as John C. Calhoun would say, “an assemblage of nations.”

Though Jefferson was a classical liberal who believed in the people as the best safeguard of their own freedoms and natural rights, he always refused the idea of a vast political community, denominated “American,” devoted to the protection of the natural rights of individuals and complying with majority rule. A lot of people tend to look to Jefferson as a democratic thinker who believed in certain features of classical liberalism. My idea of is quite the opposite. Jefferson was a classical liberal who had the idea (a bizarre idea, some would say) that the people were the best guardians of their own natural rights. In those times I guess you could think so. After having seen the people voting themselves into tyranny so many times over the last two centuries, it’s difficult to share his belief that the people are the best guardians of their natural rights. A friend of mine recently pointed out that a beer has warning labels all over it, saying not to drink beer while pregnant, and so on. But a beer is only four-percent alcohol. Drinking one beer isn’t going to do much to a person. But then you go to the ballot-box and there are no warnings on the ballots. There should at least be written: “People elected Hitler exactly this way! Be really careful who you vote for!” But there are no warnings. There’s no Surgeon-General for voting. There really should be one.

When you think about Jefferson, his anxiety about the ever-increasing consolidation of powers in the Federal government recurs over and over in his writings. It begins in 1791 or ’92 and goes on until 1826, the year he died. This is because Federalism was not just the manner in which the American republic had been structured, but something much more important. For Jefferson, Federalism was the very essence of the American experiment in self-government. Jefferson used terms like “monarchical” and “Anglophile” to describe his opponents. He didn’t care that they probably had no intention of importing a monarch to America. What he sought to stress was the nature of the English model they were trying to impose on America. The essence of that model, as he saw it, lay in the parliamentary sovereignty typical of the English system. This had been produced by the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and in practice parliamentary sovereignty had stably supplanted the idea of popular sovereignty at the end of the Second English Revolution. So, the doctrine of popular sovereignty in England (and in France one-hundred years later) morphed and twisted into the idea of parliamentary and national sovereignty (the latter much more so in France). Jefferson was convinced that parliamentary sovereignty was just as dangerous and tyrannical a notion as the concept of monarchy itself, and was in fact indistinguishable from monarchy in many ways. The Virginian had grasped something that eluded many of his contemporaries (and many people today as well): Parliament is the true heir of the sovereign, and Congress in particular represented the true heir of the English Crown. So, the struggle of political enlightenment risked being reproduced indefinitely if the new sovereign, the assembly, were not bound by well-defined fields of action and very strict limitations. Only in this context can one fully appreciate the significance of Jefferson’s statements on the non-existence of a Federal common law. Jefferson claimed (and Madison proved in the Report of 1800) that there was no Federal or general common law for the United States. There were as many common laws as there were States; there was none on the Federal level.

Jefferson also insisted that the Bill of Rights was a limit applying only to Federal power. He went on, in the Kentucky Resolutions, to assert the preeminence of the States vis-à-vis their agent, the U.S. government. Jefferson feared what we today would call “juridical globalism,” the Hobbesian idea that ultimately there will be one single government ruling the entire globe. Centripetal control over any kind of self-governing community is what the modern Left wants to achieve; they want to create a single center from which this globalization can be controlled in order to establish a single government for the whole world. That was Jefferson’s paramount fear. In 1795, Immanuel Kant stated in Perpetual Peace that such a government was necessary because the only way to achieve lasting peace was to establish one single government all over the world. These ideas were already current in Jefferson’s time, and that was his real fear – juridical globalism. Not globalization of markets or movement of people, but juridical globalization, the establishment of one single power to govern the globe.

Let us examine the nature of the Union. The strong postulate on which the entire Jeffersonian construct of the rights of the States is grounded is the analogy between the relations among the men in a state of nature and the relations among the States within the federal compact. The ratification of the Constitution notwithstanding, the States find themselves facing one another while still fully endowed with all their natural rights, exactly like individuals in the state of nature. Jefferson was a true Lockean and he believed the pre-political state to be perfectly moral and already well-governed by the laws of nature. Likewise, he held municipal laws to be acceptable only insofar as they were a reflex of natural law. The most important thing is that there exists no common judge among the parties to the Constitutional compact. Among the States, the transition to political society simply has not taken place. Since the parties cannot appeal to a judge, they are therefore sovereign in establishing a just remedy for the violation of the compact. In those times (as in ours) the objection would immediately be: “What about the Supreme Court?” According to Jefferson (and a good many other people in those days), the ultimate judge could in no way be the Supreme Court, because it was a creation of the compact itself. The Supreme Court didn’t exist prior to the Constitutional compact; creatures cannot rule over their creators. Moreover, the Supreme Court is merely a department of the Federal government. The first judge of the compact was the State, the original party to the Constitutional compact. What of the final arbiter? Jefferson appealed to Article V of the Constitution, which clearly says the final arbiter is the supermajority of the States. That supermajority can do whatever they like with the Constitution. They can amend it, they can throw it away and make a new one, or they can do without any Constitution and break up the compact entirely. Jefferson wrote:

“The ultimate arbiter is the people of the Union, assembled by their deputies in Convention, at the call of Congress, or of two thirds of the states. Let them decide to which they meant to give an authority claimed by two of their organs. And it has been the peculiar wisdom & felicity of our constitution, to have provided this peaceable appeal where that of other nations is at once to force.”[1]

The ultimate arbiter is the people of the Union acting together to amend the Constitution. If you want to change it, fine, just do it the proper way. That was the ultimate claim of the States’ Rights school: “You want a new compact, a new Constitution? There’s Article V. Let’s go for it and see what happens.” Thus, it is the people who have the final word, not a metaphysical and Constitutionally non-existent American people assembled in a single mass, but rather the peoples of the various States, represented in conventions with the aim of amending, abolishing, or modifying the government of the Union, exactly as prescribed by Article V of the Constitution.

Beginning in 1832, James Madison started writing the Notes on Nullification in opposition to John C. Calhoun. Madison thought Calhoun’s doctrine was against the Union, and since he was supposed to die as “The Father of the Constitution,” he didn’t want anything to do with Calhoun’s theory. Of course, Calhoun also had the nerve to always refer to the Kentucky Resolutions and the Virginia Resolutions, the latter of which Madison himself had written. Madison’s objection to the power of interposition (and this was Madison at his worst) was that Calhoun wanted the interposing State to make a little call to the other States to see what they thought about a given Federal law or ruling, just an opinion poll without real power. Thus, Madison insisted that the power of interposition or nullification does not exist. In saying this, Madison contradicted both Jeffersonian doctrine and what he himself had written in 1798 and 1800 (and he also misrepresented Calhoun’s position).

Calhoun took up the Jeffersonian theory and rendered independent of the contextual framework of natural law and natural rights. He defended it purely on the basis of the sovereignty of the individual States. That was a clear difference between Jefferson and Calhoun, once caused by the times; by the 1830’s, the doctrine of natural rights was losing popularity in the United States (as it was everywhere else in the world). In his Disquisition on Government, Calhoun repeatedly implies the idea of natural law, but never the idea of natural rights. One reason Calhoun should be considered a great philosopher, or at least an interesting one, is that he’s probably the first philosopher to use natural law against natural rights. On the other hand, for Jefferson the natural law model of Lockean inspiration was definitely enough, and once it had been transposed by pure analogy from individuals to the States, that was all anyone needed to properly grasp the nature of the American Union. Jefferson never appealed to the theory of sovereignty, a term that does not appear in the Kentucky Resolutions or in virtually any of his other writings. In order to claim that the States are free and independent, it is really the nature of the Federal bond that makes them such, and not their character as original political communities.

Thomas Jefferson’s greatest mistake was the Embargo of 1807. The New England States (rightly) did not like the embargo, and started to feel that the Union was actually dominated by Southern States. This view was especially strong in Massachusetts, where a common complaint was that they were under the saddle of Virginia, a complaint that grew louder after James Madison’s Presidential victory in 1808. The Federalist Party had essentially been relegated to New England. Starting in 1809, New Englanders began calling for secession in the public press. Here’s one such appeal from a Boston newspaper:

“The Constitution is a treaty of alliance and confederation. Whenever it is violated, it is no longer an effective instrument and any State is at liberty, by the spirit of that contract, to withdraw itself from the Union.”

Four years later, as the War of 1812 raged, anti-war and anti-republican protestors joined together in opposition to Madison’s new embargo, and it must be noted that while they rightly hated the embargo, the State courts were already defying the Federal government. Both in 1807 and in 1814, it was impossible to get a conviction for violation of the embargo in State courts. There was a cry to dissolve the “connexion” (sic) with the Southern States. A clergyman from Newbury said the Union was already dissolved and was time to take proper measures to ensure that “this portion of the Dis-united States can take care of itself.” The Hartford Convention was called as a measure against the embargo of December, 1813. By January, 1815, the war was over. The Convention suffered from bad timing, however, meeting during the final battle of the war, the Battle of New Orleans. We don’t know much about the proceedings because they were secret. By the way, the Philadelphia Convention was supposed to be secret in all its proceedings. That’s why Alexander Hamilton was comfortable giving a six-hour long speech in which he presented a plan to abolish the States and create a Senate and Presidency with life-time appointments. If the truth of his plan had gotten out to the press, his career would have been over, but he was confident it wouldn’t because the first thing the delegates at Philadelphia did was swear an oath of secrecy. The Hartford Convention was even more well-concealed, so we don’t know the details of what went on. Most historians believe there was no open talk of secession at the Convention. How they know this is a mystery to me. The available sources are few and scattered and we don’t know what was discussed. They might have been talking about secession the whole time. What’s clear is that the report that came out of the Convention was quite moderate. Although it stated the cause of the nation’s plight was radical and permanent, it also said the dissolution of the Union, especially in time of war, could only be justified by absolute necessity. The report borrowed from the Kentucky Resolutions of ’98 in one crucial passage:

“in cases of deliberate, dangerous, and palpable infractions of the Constitution, affecting the sovereignty of a State, and liberties of the people; it is not only the right but the duty of such a State to interpose its authority for their protection.”

This is Jeffersonianism at its best, but the report was endorsed by pretty much the same people who, sixteen years earlier, said that Jefferson and Madison were totally crazy. 71% of them were the exact same people. So, when there are real interests at stake and the North feels the Union isn’t working for its advantage, they act pretty much like Southerners and use the exact same arguments. It’s just that for most of American history, the North felt the Union was working to its advantage.

The report proposed a list of seven Constitutional amendments, all devised to curtail the influence of the Southern States, and Virginia in particular. Young Daniel Webster praised the outcome of the Convention, as did the aged John Jay. The report was moderate, but it had to be moderate because of timing. The report came out as the war was ending and the idea that the problems caused by the embargo were going away was quickly gaining steam. The Hartford Convention was thus a failure and the death blow of the Federalist Party, but the only enduring bequest of the Convention is what we care most about – it rendered the doctrine of nullification and interposition perfectly legitimate in national politics.

In 1832, South Carolina, in a Convention elected exactly for that purpose, nullified the Tariff of Abominations. The tariffs of 1828 and 1832 were declared “null and void” and the collection of all such duties was forbidden within South Carolina. You have to remember that South Carolina was the only State to really nullify a law and later on the first State to secede. The other Southern States were very prudent and didn’t adopt anything of that sort. Instead, they sat and watched the match – U.S. Government vs. South Carolina. Then-U.S. President Andrew Jackson believed that Federal laws should be respected no matter the cost, and in January 1833, he asked Congress to approve a Force Bill to authorize the Federal government to use military force against South Carolina. Congress passed the bill officially authorizing the Federal government to use force against a State. Violence was avoided when a compromise tariff was adopted which lowered the tariff rates very gradually to a maximum of 20% in 1842. The South Carolina Convention revoked its nullification of the tariff, but, in a final act of defiance, it nullified the Force Bill. In one sense, both sides could claim victory, but Calhoun was totally correct when he observed that the battle had just begun.

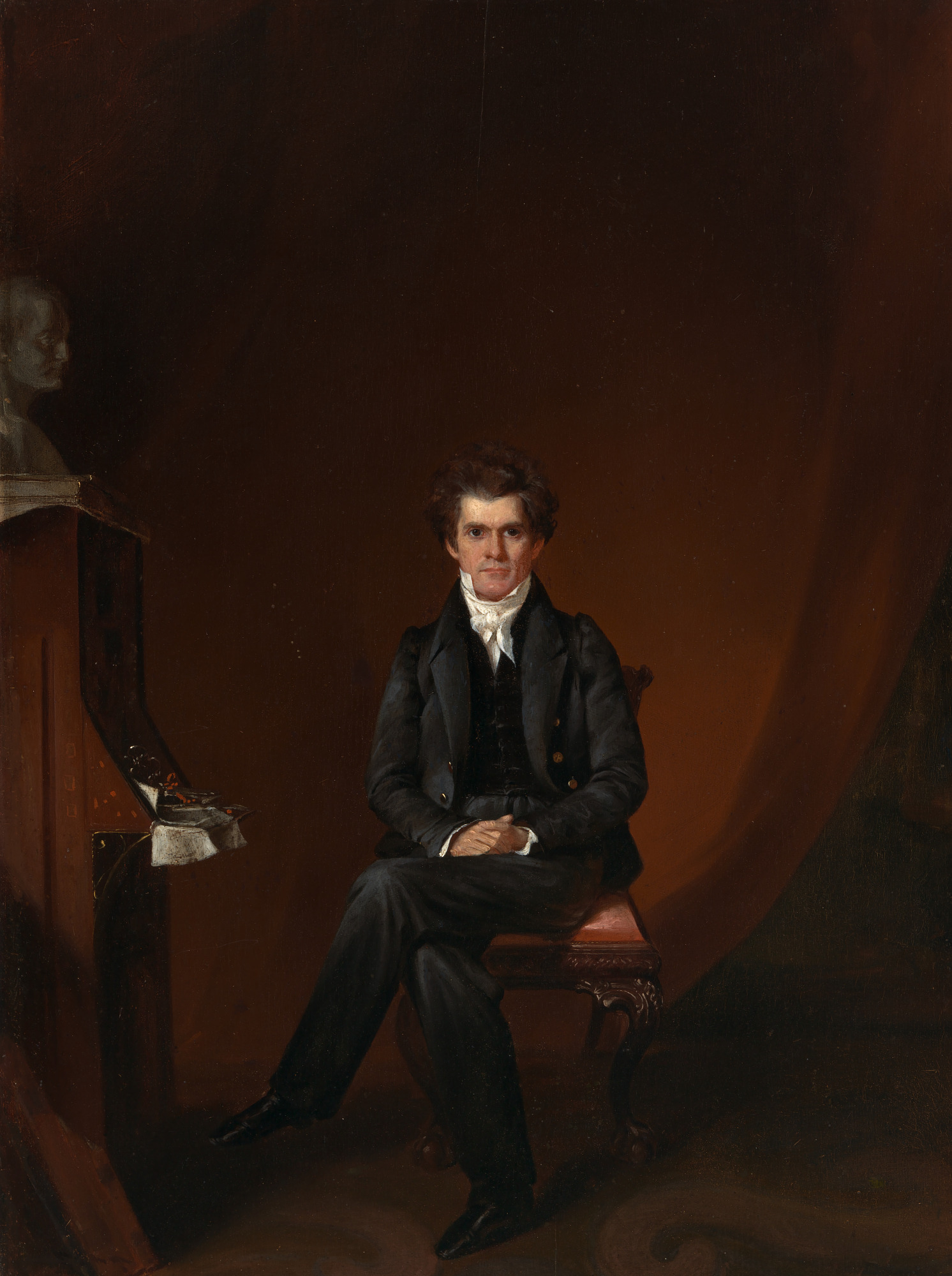

It was during this battle over the Tariff of Abominations that John C. Calhoun became the most eloquent spokesman for the States’ Rights position. Both his criticism of the tariff and his protest against the vehicle of its enforcement employed a specific vision of the Union and the Constitutional relation between the general government and the States. Nullification itself triggered two other constructions of Federalism. Daniel Webster led the development of a fully nationalist position and perfectly embodied the absolute centralist end of the political spectrum. Andrew Jackson and his Secretary of State, Edward Livingston, carved out a third position which could accurately be called “very moderate federalism.” The Nullifiers could be called “radical federalists” or simply “federalists,” because they believed in the Union as a federal republic. The conflict between these three views of the Union peaked during the winter of 1832-1833, when the Nullifiers proved successful in establishing their position as the real bulwark against the consolidation of powers. The victory they won was mostly a tactical victory, but it was a victory from the theoretical point of view. Their position was accepted and people started discussing it seriously. I am here discussing Calhoun, but the positions of Webster and Jackson should be taken into consideration. Calhoun’s arguments offer the best representation of the States’ Rights position, embodying the most political, sustainable, and fully articulated radical federalist position. Jefferson’s writings, Madison’s Report of 1800, and Calhoun’s works stand as the things you really need to know to be conscious of the States’ Rights tradition. There are, of course, a lot of other writings on the subject, but those are the essential, indispensable ones.

Nullification was both a specific action and a means to achieving Calhoun’s broader conception of Federalism. Repeatedly invoking Jefferson and the spirit of 1798, Calhoun portrayed nullification as the logical extension of the State interposition that lay at the base of republican politics. But nullification was a step beyond the 1798 Resolutions, for while both nullify an unconstitutional Federal law and pass a local measure to that end, Calhoun’s nullification no longer appeals to the views of the sister States. They’re all involved in the amendment process, to be sure, but there is no temporizing. Each State does what she has to do. Moreover, Calhoun added an innovation by requiring that a popularly elected convention issue the nullification ordinance rather than it being issued by a State legislature. Of course, this meant that popular sovereignty, the only kind of sovereignty Calhoun really talks about, had to become the voice for grave measures such as nullifying a Federal law. There’s a clear call for popular sovereignty through the ad hoc convention. So, the case for nullification could be presented as a necessary counterweight to the power of judicial review. Since the Federal courts are necessarily partial in any conflict between the general and State governments and incompetent to address many of the key issues in Federal-State relations, you actually need a veto by the State. The key idea is that Federal-State tensions must be settled politically, not by the courts. The points of conflict aren’t legal issues, they’re political issues, and they should be resolved via political means. By providing each State with a provisional veto over Federal actions (I call it provisional because it can be overruled by a supermajority of the States via the amendment process), nullification would elevate each State’s power to interpret and enforce the limits of Federal power delegated under the U.S. Constitution to a role similar to that already exercised by the courts and the President. It was a veto by the State.

Calhoun’s doctrine of nullification was predicated on a particular and peculiar vision of the Union. The Tenth Amendment is the cornerstone of the American Federal polity, but many legal scholars have held that it conflicts with Article VI, which allegedly establishes a Federal supremacy clause. Calhoun’s objection to this interpretation is very powerful:

“It is sufficient, in reply, to state, that the clause is declaratory; that it vests no new power whatever in the government, or in any of its departments. Without it, the constitution and the laws made in pursuance of it, and the treaties made under its authority, would have been the supreme law of the land, as fully and perfectly as they now are; and the judges in every State would have been bound thereby, any thing in the constitution or laws of a State, to the contrary notwithstanding. Their supremacy results from the nature of the relation between the federal government, and those of the several States, and their respective constitutions and laws. Where two or more States form a common constitution and government, the authority of these, within the limits of the delegated powers, must, of necessity, be supreme, in reference to their respective separate constitutions and governments. Without this, there would be neither a common constitution and government, nor even a confederacy. The whole would be, in fact, a mere nullity. But this supremacy is not an absolute supremacy. It is limited in extent and degree. It does not extend beyond the delegated powers; all others being reserved to the States and the people of the States. Beyond these the constitution is as destitute of authority, and as powerless as a blank piece of paper.”[2] (emphasis added)

This is a very clear objection to the idea that there is a supremacy clause. There is no supremacy in there. Clearly, there is a Constitution, but there is nothing else, no new powers. Federal laws are supreme only within the limits of the delegated powers. Calhoun goes on to dismantle the centralized interpretation of the American Constitution and draws a distinction between sovereignty and the exercise of sovereign powers. The States never relinquished their sovereignty. They merely decided their sovereign powers were going to be used by the general government in certain instances. Delegation of power for specific purposes didn’t divest the States of their sovereignty. Moreover, having delegated the powers, the State(s) can reclaim them whenever they please. As the constant refrain of the States’ Rights school goes: “In no instance can the creation overcome the creator.” The creators were the States and the creation was the Federal government. The Federal government is not co-equal with the States. It is simply an agent, an agent which did not exist prior to the Constitutional compact. The power to amend the U.S. Constitution is the fulcrum of each State’s sovereignty and the ultimate proof of its natural place in the American compact. According to Calhoun, Article V of the Constitution shows conclusively that the people of the several States still retained that supreme, ultimate power, the same power by which they ordained and established the Constitution and which can rightfully create, modify, amend, or abolish that Constitution. The peoples of the States can abolish the Constitution at their pleasure. In the last analysis, the problem of the nature of the U.S. government, according to Calhoun, could be reduced into one single question:

“Whether the act of ratification, of itself, or the constitution, by some one, or all of its provisions, did, or did not, divest the several States of their character of separate, independent, and sovereign communities, and merge them all in one great community or nation, called the American people?”[3]

Of course, you know the answer. The United States is not a nation, but an assemblage of nations, or of member peoples of their respective political communities, the States. As Calhoun put it:

“Ours is a Union, not of individuals united by what is called a social compact, for that would make it a nation, nor of governments, for that would have formed a confederacy like the one superseded by the present Constitution, but a Union of States founded on a written, positive compact forming a federal republic with the same equality of rights among the States composing the Union as among the citizens composing the States themselves.”

The fact that these States entered into a relation with other States to form a compact using a common agent did not change their status as sovereign political communities. The whole point of Calhoun is that when the general government uses its power it is merely the agent of the States. Whenever there is an arrogation of powers, it is not valid. It would be like paying a man to buy you a $100,000 home in South Carolina and him going to North Carolina, buying you a $75,000 house, and pocketing the difference. The general government is just the agent of the States, nothing more. In relation to each other, the State and Federal governments are equal and coordinate, but from the view of the sovereign (the peoples of the States), they are simple agents which can be ordered, changed, or repealed by the people at will. The real sovereign in the American system is the peoples of every single State. “Sovereignty is not in the government,” said Calhoun, “it is in the people. Any other conception is utterly abhorrent to the ideas of every American.”

On 26 February 1833, Calhoun introduced to the Senate three resolutions on States’ Rights which represented the core of his principles on the nature of the Union:

“Resolved, That the people of the several States composing these United States are united as parties to a constitutional compact, to which the people of each State acceded as a separate sovereign community, each binding itself by it own particular ratification; and that the Union, of which the said compact is the bond, is an union between the States so ratifying the same.

Resolved, That the people of the several States, thus united by the constitutional compact, in forming that instrument, and in creating a General Government to carry into effect the objects for which they were formed, delegated to that Government, for that purpose, certain definite powers, to be exercised jointly, reserving at the same time, each State to itself, the residuary mass of powers, to be exercised by its own separate Government; and that whenever the General Government assumes the exercise of powers not delegated by the compact, its act are unauthorized, and are of no effect; and that the same Government is not made the final judge of the powers delegated to it, since that would make its discretion, and not the Constitution, the measure of its powers; but that, as in all other cases of a compact among sovereign parties, without any common judge, each has an equal right to judge for itself, as well of the infraction as of the mode and measure of redress.

Resolved, That the assertions that the people of the United States, taken collectively as individuals, are now, or ever have been, united on the principle of the social compact, and as such are now formed into one nation or people, or that they have ever been so united in any one stage of their political existence; that the people of the several States composing the Union have not, as members thereof, retained their sovereignty; that the allegiance of their citizens have been transferred to the General Government; that they have parted with the right of punishing treason through their respective State Governments; and that they have not the right of judging in the last resort as to the extent of the powers reserved, and, of consequence, of those delegated; are not only without foundation in truth, but are contrary to the most certain and plain historical facts, and the clearest deductions of reason; and that all exercise of power on the part of the General Government , or any of its departments, claiming authority from so erroneous assumptions, must of necessity be unconstitutional, must tend directly and inevitably to subvert the sovereignty of the States, to destroy the federal character of the Union, and to rear on its ruins a consolidated Government, without constitutional check or limitation, and which must necessarily terminate in the loss of liberty itself.”[4]

You might be interested to know that none other than Carl Schmitt, probably the greatest political theorist of the 1900’s, understood the importance of Calhoun’s thesis. In The Guardian of the Constitution, Schmitt said:

“[Calhoun’s theses] remain theoretically crucial for a constitutional theory of federation and are not made irrelevant by the fact that the Southern States were defeated. Calhoun’s doctrine deals with key concepts in the constitutional theory of federation. The task here is not to prove that the United States today is a federation, but rather to pose the question without preconceived notions and phraseology, whether today there is some sense in which it can still be called a federation, or whether only the remnants of an earlier federation have been deployed in the construction of a unitary state, or whether true federal elements have been transformed gradually into the organizational elements of a unitary state.”

Carl Schmitt was on to something. Calhoun and the entire South became obstinate in their belief that the U.S. was an authentic federation, that the Constitution was a tool attributing amending powers to three-fourths of the States, and ascribing governmental functions to a superstructure established to administer common matters did not substantially change the contractual and voluntary character of the association between the States. But, as we know, history was moving in another direction.

I would like to briefly examine the nature of the relationship between nullification and secession in Calhoun’s view. Jefferson was certainly in favour of secession when liberty was at stake. In his last public document, which was written in 1825 for the Assembly of the State of Virginia, Jefferson wrote: They [the General Assembly] would, indeed, consider such a rupture as among the greatest calamities which could befall them; but not the greatest. There is yet one greater, submission to a government of unlimited powers.” This is classic Jefferson, but the thing is that Jefferson was not proposing a way to render this right a Constitutional one. He was still thinking of secession in terms of the right to revolution, in Lockean terms. In this sense, there’s not much difference between Thomas Jefferson and Daniel Webster, the latter of whom repeatedly insisted that there was no legal right to secession because it was revolution. Jefferson dropped the ball here, because he never made it clear that you could escalate from nullification to secession if necessity demanded. He never thought to link the two. Because of this, we might well ask: “What is the relationship between nullification and secession?” The answer is to be found in the writings of John Caldwell Calhoun, especially in his letter to Governor Hamilton. Although Calhoun considered himself the heir of Publius and merely devoted to correcting the errors of The Federalist, his interpretation of the Constitution opened new roads, and within the framework of the Compact Theory of the Constitution, his reflections put forward a doctrine of secession in a free federation of States like the one most Americans thought they lived in during the years between the ratification of the Constitution and the election of Abraham Lincoln. The key thing to understand is that Calhoun’s is a Constitutional doctrine of secession. In other words, it is a doctrine of legal secession rather than an appeal to the right of revolution.

According to Calhoun the States are the masters of the federation, and the Federal government is merely the administrator of such an organization. Therefore, secession is the act of withdrawing from that partnership. It is a resolution of that compact between the members, and as such, it frees the withdrawing member from any obligation it previously had vis-à-vis the other members. Secession has nothing to do with the Federal government, because the Federal government is simply the caretaker of the federation. Secession involves only the relationship between the several States. Nullification, on the other hand, is the act by which one of the parties to the compact declares formally that the agent (i.e. the Federal government) has exceeded its delegated power, and its acts are therefore null, void, and of no force, at least within the territory of the State has objected against such an arrogation of power. Calhoun called this “the great conservative principle of the federation.” He believed the power of nullification/State interposition was the only way to preserve the federation on a purely voluntary basis. In this sense we can say that the act of withdrawing from the Union is external, but not estranged from the political and Constitutional order. It is only within such a conceptual framework that we can understand the escalation of purely Constitutional means, going from the Federal arrogation of power to State nullification, to the call of the final arbiter, the supermajority of the States and eventually, after that, to secession. In this sense, nullification is a potent cry from a State saying to the other States: “Our agent has gone too far! If you believe it is proper to grant the agent such powers, let’s proceed in the Constitutional fashion, let’s come up with an amendment to give the Federal government that kind of power.” Nullification is a way to flag that a change in the compact has taken place because new Federal powers have been construed. If these powers are actually granted by the qualified supermajority of the States, then the nullifying State has a clear choice, either to accept a Constitutional amendment it may find objectionable, or to leave the compact. Strictly speaking, the amended compact is a new compact. If a State refuses to agree to this new Constitution, it is not seceding from the old compact, but rather is refusing to accede to a new compact. This wouldn’t happen every time the Constitution is amended, but only when a State has nullified a Federal law and that law has subsequently been made Constitutional via an amendment granting expanded powers to the Federal government. Not every amendment fundamentally alters the nature of the compact, but one which expands Federal power most certainly does; such a fundamental alteration constitutes a new compact to which each State must accede (or not) of its own free will. Calhoun declares this with the utmost clarity:

“Nullification may indeed by succeeded by secession, and in the case stated, should the other members undertake to grant the power nullified, and should the nature of the power be such as to defeat the object of the association or Union, at least as far as the member nullifying is concerned, it would then become an abuse of power on the part of the principals and thus present a case where secession would apply, but in no other cases could it be justified.”

Calhoun’s position is thus a very qualified right of legal, Constitutional secession. Only the nullifying State can have a legitimate claim to withdraw from the Union, and only under specific conditions. Calhoun never talked lightly about secession. Sure, it was a possibility deriving entirely from the American compact, but he was definitely more worried about another, much more effective way of breaking up the Union: “Dissolution is not the only mode by which our Union may be destroyed. It is a federal Union, a Union of sovereign States, and can be as effectually and much more easily destroyed by consolidation than by dissolution.” Like Jefferson and the Anti-Federalists, Calhoun was a prophet. We’re living with the consequences of the dissolution of a federal Union of sovereign States brought about by consolidation, not secession. Thank you.

[1]Jefferson to William Johnson, 12 June 1823. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-3562

[2]Calhoun, A Discourse on the Constitution and Government of the United States, from Works of John C. Calhoun, Volume I (1851), 252-253.

[3]Calhoun, A Discourse on the Constitution and Government of the United States, from Works of John C. Calhoun, Volume I (1851), 121.

[4]Calhoun, “Speech Introducing Resolutions Declaratory of the Nature and Power of the Federal Government,” The Essential Calhoun, ed. Clyde N. Wilson (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2000), 292-293.

curious…with the embargos that were passed, was this in any way benefitting the south over the north in anyway…or a military measure? how ould an embargo make the south wealthy?