The concept of a faithful slave goes against today’s authorized slave narratives. Before the social upheavals of the 1960s, it was still permissible to depict different reactions of slaves towards their masters; all slaves didn’t have to be portrayed as resentful. Admittedly, most slaves wanted freedom and many slaves were mistreated and consequently bitter towards their masters. Indeed there were slave revolts. But there were numerous slave-holders who could be described as benevolent and many of their slaves responded by remaining essentially faithful to their masters. So, even though it conflicts with the stereotypical portrayal of harsh treatment of slaves by masters, there were exceptions.

During her tour of America in the 1800s, the self-proclaimed authority on social conditions, English noblewoman Harriet Martineau encountered lenient slave-holders. In her 1837 two-volume study, Society in America, she describes a South Carolina slave-holder who refused to abandon his slaves during the cholera epidemic, even though most of his neighbors fled the state. This man personally nursed his slaves, administered medicines, assisted them with bathing and grooming, and helped them fight discouragement, exposing himself to the ravages of this deadly disease all the while. Miss Martineau stated: “A far higher strength than that of self-interest was necessary to carry this gentleman through such a work.”

Even Harriet Beecher Stowe’s celebrated anti-slavery polemic Uncle Tom’s Cabin portrays faithful slaves. In one scene, Tom’s master sends him to Cincinnati to complete a business transaction and bring back several hundred dollars. The slave is presented with a golden opportunity, not only to gain his freedom, but to attain long-range financial security by keeping the enormous amount of money he has in his possession. But the loyal Tom does not take advantage of being in the Northern city of Cincinnati; the hub of the underground railroad, where so many slaves had been helped to freedom. Tom returns to his master with the money he has collected for him.

Tom’s first two owners were Southerners and more charitable towards the slave than his final owner, the sadistic Simon Legree, a Yankee transplanted to Louisiana. In the 1850s, Mrs. Stowe could offer a literary work that depicted both faithful and rebellious slaves as well as benign and brutal masters. But only mistreated slaves and malicious masters are found in today’s authorized slave narratives.

Famous Atlanta newspaper journalist, Joel Chandler Harris was pleased with Mrs. Stowe’s favorable portrayal of Uncle Tom’s two Southern masters, who treated the slave kindly. Stowe’s depiction of Tom as a wise slave who had the love and esteem of his owner’s family greatly influenced Harris. He claimed that Uncle Tom’s Cabin inspired him to write his classic Uncle Remus stories. Harris had considerable experience with slave traditions and narratives, as he spent much of his childhood on a plantation. The Uncle Remus stories, published about thirty years after Mrs. Stowe’s book, are a significant contribution to our literature, even inspiring a 1940s film, Song of the South. But, with the advent of the 1960s, a slave could no longer be portrayed as genial or good-natured, so both the Uncle Remus stories and the film have become targeted victims of cultural cleansing.

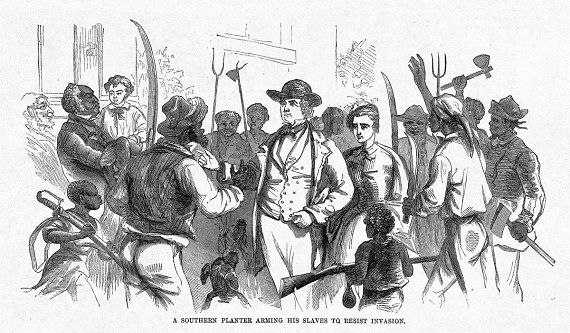

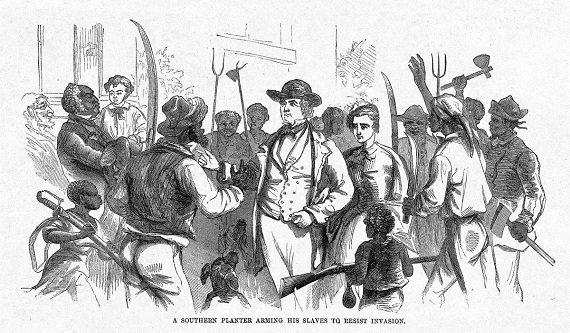

Even after realizing that the South had been defeated in the War Between the States, many slaves refused to abandon their fidelity to their masters. There are numerous recorded incidents of slaves hiding their owners’ valuables while General Sherman’s Union forces marched through Georgia and South Carolina leaving a path of destruction, confiscating or destroying everything of value. Even when subjected to torture, these heroic slaves refused to reveal where family valuables had been hidden.

Throughout the South, local communities have erected monuments acknowledging and honoring loyal slaves. A historical marker paying tribute to Neptune Small, a slave born and raised on one of St Simons Island’s plantations, is located near the Island’s ocean pier. During the War Between the States, Neptune served as bodyservant to a Confederate soldier; a member of his master’s family, with whom he had bonded. When this soldier was killed in action, Neptune searched the battlefield until he found the body, which he brought home for burial in the family plot. After emancipation, Neptune remained with his master’s family who awarded him with land, where he built his home and lived out his life with his wife and children.

Heyward Shepherd was a freed slave in Harpers Ferry who accommodated himself to the white community. He worked as a railroad porter and often managed the ticket office. Sometime after midnight on October 16, 1859, Shepherd was walking near the railroad bridge, when he accidentally encountered John Brown’s raiders sneaking into the city. Brown’s forces wanted to capture the federal arsenal and confiscate its guns and ammunition. John Brown felt that when local slaves learned that he had taken control of the arsenal, they would abandon their masters and join his forces. But none of the local slaves joined Brown. His raid failed and he was arrested.

Freed slave Heyward Shepherd was shot in the back as he attempted to flee Brown’s raiders, but he managed to make it back to the train station and warn of the raid before he died. The city’s 1931 monument to honor Shepherd has been an ongoing source of controversy. Many consider his action heroic, but the NAACP does not feel that a freed slave who tried to protect the white community should be celebrated. That organization maintains that if a white community honors a slave, it weakens the stereotypical depiction of ill will between slaves and masters. Also, to pay tribute to Shepherd for warning the community implies that John Brown’s raiders were prone to mayhem and violence. This conflicts with the sanctioned depiction of Brown as a noble man on a righteous crusade. Failing to get Harpers Ferry to remove the Shepherd monument, the NAACP countered with a monument honoring John Brown.

On February 15, 2014, a celebration was held in the city of Charleston for the dedication of a newly erected monument honoring Denmark Vesey. There is also a controversy over this monument venerating Vesey, who was a freed slave who covertly organized thousands for an uprising to murder Charleston’s white citizens while they slept, burn the city, and put freed slaves on ships to Haiti.

Luckily, the slaughter was avoided when two guilt-stricken slaves revealed the plot. Vesey and the major conspirators were arrested, tried, convicted of treason, and hanged. The Vesey monument has the enthusiastic support of Charleston’s long serving Democratic mayor, Joseph Riley, as well as the NAACP. We assume that Riley and the NAACP believe that the end justified the means if slaves could be freed.

Speaking at the celebration, black professor Bernard Powers, used strained academese to characterize opponents of the monument: “They don’t have the conceptual framework or proper vocabulary to understand Denmark Vesey.” Admittedly, countless persons, including myself, do not “understand.” Indeed, we cannot “understand” why Charleston is paying tribute to someone who plotted the indiscriminate massacre of the city’s white population. The city could have honored many other famous black citizens whose accomplishments don’t involve mayhem or planned executions. The choice of a monument honoring Denmark Vesey can only be described as deliberately contentious.