From the 2003 Abbeville Institute Summer School

This morning we’re talking about the two greatest losers in American history. “Loser’s History” is the only history that needs to be told. With the winners, you know everything about it, even if you don’t care to know it; just turn on the History Channel. My suggestion is to never watch the History Channel if you want to learn something about history. That was a great line by Ralph Raico. Whenever you watch the History Channel, you get the official view of how things were and I think you should avoid that unless there’s some good documentary. They occasionally get things right. Now, we’re going to be talking a lot about Jefferson and Calhoun. I do believe that these two guys, Jefferson and Calhoun, are the best and the most powerful intellectuals that America ever produced, and were it not for their being too interested and involved in actual politics, they would compare with Immanuel Kant, John Locke, David Hume, even G.W.F. Hegel, the great minds of humanity. Unfortunately, they were distraught by practical politics, as happened to a lot of Americans in those times. For a long time, Americans had this inferiority complex against Europe for almost 200 years until the end of the Second World War. Americans accepted Tocqueville’s explanation of themselves for more than a hundred years. Here’s this brilliant Frenchman who comes to the United States, doesn’t speak a single word of English, goes around with a couple of translators, talks to some people, is here to take a look at the prisons more than anything else, goes back, and writes a brilliant book about America. There’s no doubt that Tocqueville’s book is excellent, but that happens to be America for a lot of people for more than a century. Tocqueville defined America. You know in Europe, for the thinkers of the 1800’s, the question was never: “Did he know anything about America?” The question was: “Did he read Tocqueville?” For Americans and Europeans alike, Tocqueville became the official explanation of America throughout the 1800’s, and my contention is that there are better sources and there are a lot of sources and Tocqueville is just one among many.

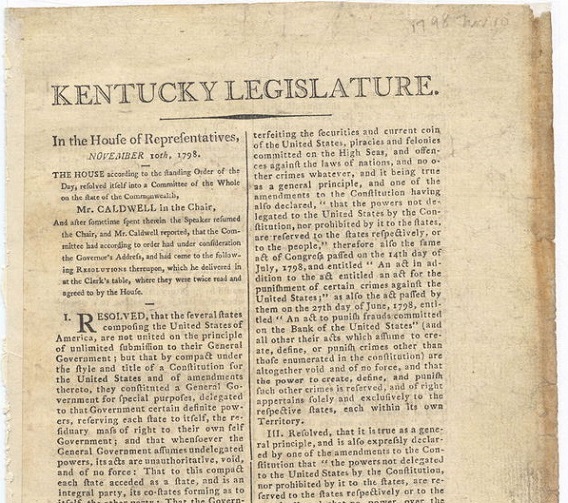

We will discuss the Jeffersonian political doctrine and something about the Hartford Convention. When I was writing this book on Jefferson, I spent five or six years with the guy, and for some months it was more than twelve hours a day spent in his writings. So, when I was reconstructing his political thought on certain issues like the right of property (which almost a-hundred-and-fifty pages on that) I just wanted to show that he was a pure Lockean in regard to property as a completely natural right, and, because of the fragmentary nature of Jefferson’s reflections on these issues, that was done by inferences and inferential arguments. But when it comes down to Jefferson’s Federalism, certainly one can say that destiny has looked more favourably upon me and us in general, because Thomas Jefferson has left us something absolutely certain and very sound on which to base our arguments – an entire document of almost 3,000 words which contains his complete theory of the Federal bond. This is, of course, the Kentucky Resolutions of 1798. In many ways this is an explosive document and is destined for a prolonged period of time to be regarded within American political history as the starting point of the school of States Rights. Jeffersonian scholars don’t like it at all because it is embarrassing for them. They are keen to create the icon of the Virginian that loved the Union just as much or even more than Abraham Lincoln. Jefferson, a guy who never considered himself an American, but just a Virginian, somehow was the builder of the nation. And so, the major Jefferson biographers tend to pass it off as worthy of no more than a few pages among thousands, a mere note out of tune which occupies a purely marginal role in the work of an otherwise crystal-clear lifetime, to be brushed aside like a bothersome fly that threatens to alight on a tasty morsel. For instance, take Dumas Malone, who wrote the definitive biography on Jefferson. He wrote his first article on Thomas Jefferson in 1926 or 1928 and the last one was in 1982. He wrote six volumes on the life and times of Thomas Jefferson and it’s easily more than 3,000 pages. Guess how many pages are devoted to the Kentucky Resolutions? Out of 3,000 pages, there are six pages on the Resolutions. Six. Malone covers them favourably, but six pages out of 3,000 makes them seem totally unimportant. The fact is that the Resolutions are really the core of Jefferson’s Federal conception and they embody in a nutshell the whole of his Constitutional doctrine. They actually represent Jefferson’s greatest contribution to a Constitution in whose drafting he took no part, since as you all know, he was in Paris, France at the time as an ambassador to Louis VXI. In a certain sense, Jefferson felt that the Federal system could almost boast a priority even over the rights of man. You know that Jefferson is the guy in American history who was the most concerned with the rights of man and the rights of the individual and so on, but at a certain point after 1798, we could even say that the real Federal system boasted priority over the rights of man. This is to say that for Jefferson, the centralized republic, consolidated, one and indivisible, was always and necessarily tyrannical even when it benefited or formally recognized the rights of man, and over time actually what happened is that it replaced the simple natural rights creed of 1776 with a Federal conception of the body politic because he came to recognize that the protective walls of our liberty are our State governments. He wrote as much to French philosopher Antoine Louis Claude Destutt de Tracy in 1811: “the true barriers of our liberty in this country are our state-governments.”[1]

In Jeffersonian terms, political tyranny would be defined as: “The consolidation of power in a single center.” There’s no other definition of tyranny in Jeffersonian thought after 1798. So, the rights of man would certainly remain at the center of his political reflection, but the strategic design to safeguard such rights came to include the reinforcement of the power of the States at the expense of the Federal government. The Alien and Sedition Acts were the two laws that prompted the response from Jefferson and Madison. Jefferson drafted the Kentucky Resolutions and Madison drafted the Virginia Resolutions. In doing this, Jefferson took the first available opportunity on which the Federalists broke the Constitutional pact in order to seriously address the entire problem of Constitutional interpretation – the relations between the Federal government and the States. These laws concerned freedom of expression pretty clearly and for a long time people just thought that what was going on was actually a battle for freedom of expression, not a battle over Constitutional interpretation. But Jefferson wasn’t defending the First Amendment. Jefferson was talking about Constitutional interpretation. The Alien and Sedition Acts were approved in the summer of 1798 and when Jefferson was vice-president and they sparked the definite split between Jefferson himself and the Federalist Party. The law on aliens was a pretty bad law, but it was not applied because in those times you became a citizen through a State, so Federal law could not do anything to you for the status of foreigner. However, the law increased from five to fourteen years the period of residence required for naturalization and post-compulsory registration of all aliens. Aliens were coming into the country and they were joining ranks with the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican Party immediately and that was something that the Federalists didn’t like. The law also gave the President of the United States the power to decree the expulsion from American soil, without any trial, of any alien citizen, which was considered pretty un-American. The Federalists didn’t have a problem with the immigrants per se, but they hated that these new arrivals were joining the Jeffersonian Party. The law on aliens was quite severe, but as I said, it was not applied at all, plus they were foreigners, so a lot of people didn’t care too much about that.

The law on sedition stated that it was an offense punishable with a fine of up to $5,000 and five years in jail to act in such a way as to prevent the full implementation of the laws of the United States or to intimidate anyone who sought to obtain a Federal office or more generally to participate in any sort of seditious assembly. Now, how do you define that? It clearly violated the First Amendment. Anyone found to be the author or publisher of defamatory material that was offensive against the President or Congress could be punished by a fine of $2,000 and imprisoned for two years and it’s difficult to know how many people were, because the old common law action for libel was still there, but we’re talking about thirty or forty very prominent people who went to jail. The basic result was that the First Amendment, the one that establishes the right of every citizen to absolute and incoercible freedom of manifesting of his own thought, was no longer enforced, superseded by a mere act of Congress in what was clearly an arrogation of power. These laws also clearly overstepped their delegated powers since no article of the Constitution delegated to the Federal government the power to regulate the status of aliens, much less the power to repeal freedom of expression.

The background of these measures was the French scare. There was a French scare in 1798. While it was clear that there should have been a French scare in Germany and all over Europe, it’s not understandable why there was something like that in the United States, but it spread like wildfire through America during the 1790’s. And it was really the fear that the French Revolution would burst its banks and spread beyond its natural borders, but as John Adams said: “There’s no more prospect of seeing a French army here than there is in Heaven.” Just after the passing of the two laws, Jefferson privately reassured John Taylor of Caroline, saying: “a little patience and we shall see the reign of witches pass over,”[2] but this proved not to be the case. and he had little patience afterwards, when his opposition to the measures could not have been more clearcut. A few years later, in 1804, he wrote to Abigail Adams, who was also a fervent Federalist: “I considered & now consider that law to be a nullity as absolute and as palpable as if Congress had ordered us to fall down and worship a golden image.”[3] If you know Jefferson, that’s a pretty powerful image. The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions were the Jeffersonian and Madisonian answer to that, and in the Kentucky Resolutions Jefferson really for the first time put forward the political and juridical doctrine of the school of States’ Rights, which retained its primacy up until the War for Southern Independence. I call it the War for Southern Independence because I think it was a war for Southern independence. It’s not a civil war because in a civil war, both sides fight to gain control of a given central government and of the same territory, which clearly was not the case. And it’s not The War Between the States because the States as States had no part in the war. There were no armies from the States. They all fought under the army of the Confederacy or the Union. So, it should be called the War for Southern Independence because that was the cause for it. The South wanted to be independent and the U.S. government wouldn’t let them go.

So, when was the beginning of this school of States’ Rights? It was during the ratification of the Constitution, and especially in Virginia, New York, and Rhode Island. New York and Rhode Island were even more specific than Virginia when they ratified the Constitution. They basically said: “The people will just get back their powers whenever they want. We do ratify the Constitution, but it has to be very clear that we can just regain our powers whenever we like.” Antifederalist feeling was extremely strong in Virginia where the Constitution plan was passed by a vote of 89 to 79 in 1788. And most of them were just conned into it. I think there was a clear majority of Antifederalists in Virginia, but they were out maneuvered. The Federalists were definitely the slicker politicians. But at the moment of ratification in the Virginia Convention they added a clause that was intended to provide a clear statement of the meaning of this traumatic act of subscribing to the new plan of government, so we should look at this for the definite birth of the States Rights’ school. They said something like:

“We the delegates of the people of Virginia do declare and make known that the powers granted under the Constitution, being derived from the people of the United States may be resumed by them” (Daniel Webster later used this same quotation to argue the exact opposite. He was another slick politician.) “whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression and that every power not granted thereby remains with them and at their will. That therefore no right of any denomination can be canceled, abridged, restrained or modified by Congress, the Senate, or House of Representatives…& that among other essential rights the liberty of conscience and of the Press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained, or modified by any authority of the United States.”

Isn’t it interesting that they’re talking about liberty of the press and liberty of conscience? So, ten years later Virginia and Kentucky found themselves leading a battle that stemmed precisely from the freedom of speech and ultimately involved the interpretation of the Constitution. Now let’s forget anything about history because although it’s really interesting, I don’t want to dwell to much on that, because otherwise we cannot talk about the theory. Let’s go to the theory. Today a large portion of political and Constitutional theory holds that Federal citizenship is unthinkable without common and uniform safeguards of rights for all citizens. That’s part of what they call Federal citizenship. The States can decide a couple of things, especially if people can have fireworks or not. Contemporary scholars unanimously agree that individual rights have the greater protection under Federal than State power. I don’t know why, but that’s a given you cannot argue about. What they want to say is that there shouldn’t be any disparity of treatment on this very sensitive issue and the equality of citizens before the law cannot be guaranteed but at the Federal level. That’s the juridical thought of these days and the past hundred years. Well, Thomas Jefferson declared exactly the opposite. It was not the Federation, but the States, the buffers against the Federalist cravings to amass the American population into a single political community, that represented the true guarantee of the freedom of the citizens. So, the Kentucky Resolutions are first and foremost a recognition of the irreplaceable role played by the States in safeguarding the Constitutional balance against the risk of consolidation of Federal power. And as we shall see on the First Amendment, Jefferson thought that the States could do something against the First Amendment, but the Federal government could not. He took “Congress shall not” very seriously. It is appropriate to cite the core of the argument set forth in the Resolutions. The first resolve said:

“the several states composing the United States of America, are not united on the principle of unlimited submission to their General Government; but that by compact under the style and title of a Constitution for the United States and of amendments thereto, they constituted a General Government for special purposes, delegated to that Government certain definite powers, reserving each state to itself, the residuary mass of right to their own self Government; and that whensoever the General Government assumes undelegated powers, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force: That to this compact each state acceded as a state, and is an integral party, its co-states forming as to itself, the other party: That the Government created by this compact was not made the exclusive or final judge of the extent of the powers delegated to itself; since that would have made its discretion, and not the constitution, the measure of its powers; but that as in all other cases of compact among parties having no common Judge, each party has an equal right to judge for itself, as well of infractions as of the mode and measure of redress.”

That’s the crucial point! That’s the crucial part of the Resolutions. There are other very important parts, but that is the most important part, because that’s the part that started the school of States’ Rights. In this resolution Jefferson asserted that the States, in as much as they were sovereign parties that formed the Constitutional compact, had created the Federal government as a nation subordinating it to their own power and designed to carry out limited and well-defined functions. The Federal government had no right to expand its own sphere of authority without the agreement of the contracting parties and, in Jefferson’s opinion, each individual State, when dealing with controversies that concerned the Constitution had the right to establish two things: First, when the pact had been breached, it was up to the State to decide that. Secondly, each State could decide the measures required to restore the order that had been disrupted. Jefferson argued in favour of the existence of a natural right of each State to declare the illegitimacy of an act of Congress deemed to be contrary to the Constitutional compact. He called it a natural right because it is based on the laws of nature, as these are the laws that best apply to powers having no common judge. Now, you have to remember that Jefferson was a pure Lockean, so you’re in a state of nature when you have no common judge, but in a state of nature there are the laws of nature that govern the state of nature – it’s not a lawless state. The view of the state of nature was quite different between Thomas Hobbes and John Locke. So, if you do not have a common judge what you have is a state of nature, and like individuals, the States are in a state of nature and the laws of nature do apply and therefore the natural right is the right to nullify. This is a purely Lockean framework. Furthermore, in the draft to the Kentucky Assembly, Jefferson had used the term “nullification” to refer specifically to that particular right – the natural right to stop a Federal law within the territory of the State because they had no common judge. This term “nullification” became very important thirty-two or thirty-three years later in American history. When they discovered that Jefferson was the author of the text, as had been suspected by a lot of people earlier on, the original version of the Resolutions was found among his papers in 1832, complete with the word “nullification.” The nullifiers scored a big point at that time because there were some articles in the Richmond Enquirer in which the editor said it couldn’t have been Jefferson. Then they found the letter and showed it to him. He was a very honest man and came out with another article admitting “nullification” was a Jeffersonian word and correct to use, because it had been struck out of Jefferson’s draft by the Kentucky Assembly.

The most crucial passage was actually the one we find in the eighth resolution of Jefferson’s draft, and it’s the measure to redress the Constitutional violation:

“that in cases of an abuse of the delegated powers, the members of the general government being chosen by the people, a change by the people would be the constitutional remedy; but where powers are assumed which have not been delegated a nullification of the act is the rightful remedy: that every state has a natural right, in cases not within the compact [casus non foederis] to nullify of their own authority all assumptions of power by others within their limits”[4]

So, in the case of ordinary abuses the remedy would be the free change of elected majorities and minorities, something that we tend to call democracy, without the States becoming protagonists in the battle. There’s no need for the States to step in if the jerks are running the Federal government. The people will take care of that supposedly. But when it becomes a question of arrogation of powers that have not been delegated, then it is both the duty and the natural right of the State that it becomes the protector of its own citizens as the underwriter of the original Constitutional pact. Since the States are the underwriters of the Constitutional pact, they have to shield their own populations from an illegal, totally unconstitutional measure. This function whereby the State protects its own citizens against the abuse of Federal power and shields them from unconstitutional laws would also be called the power of state interposition. The resolutions of the two Virginians concluded with an appeal to the co-states urging them to orchestrate common actions in order to expel the monstrosities represented by the 1798 laws from the legal system.

So, how was the Kentucky doctrine received in America? One clear division to emerge was its sectional character. South of the Potomac, the States simply did not respond to the exhortations because they were not strong enough. The Jeffersonian Party was gaining support but it was still too weak to pass resolutions of that kind and all the Northern States protested loudly through their assemblies, asserting first and foremost the full legitimacy of the Alien and Sedition Acts. Now, the fact that they were defending the Constitutionality of those laws tell you something. They didn’t say, “you are obliged to follow the general government whatever they say,” they just argued, “these are perfectly Constitutional laws so you have to follow them.” In those times nobody would have said something like: “It doesn’t matter. It comes from the Federal government, so tough luck because of the Supremacy Clause.” Nobody talked about the Supremacy Clause. Actually, the difference was that of a political nature and in the Southern States Jefferson’s Party was gaining strength, while the whole of the North was still in the hands of the Federalists. Thus, the tone of the States’ responses varied widely, but the leitmotif was that the States were not empowered to judge Federal laws for which there already existed one arbiter: the Supreme Court. So, they just said it’s up to the supreme court to see if it’s constitutional or not. The nature of the American Union as a pact and as a contract entered into by those who were parties to the pact was called directly into question. So, for the first time in 1798 you have the school of states rights at the beginning of that, but then in the answers you see something else – the beginning of the nationalist interpretation which was proclaimed most loudly by the infamous State of Vermont.

For the first time in history, Jefferson and Madison put forward the theory that the Federal government was created by a compact between the States and we the people acceded only as States and the States became not only the legitimate judges of the Constitution, but the executors of their decisions with regard to the Constitutionality of Federal laws. This precise point was directly refuted by Vermont, whose assembly ventured into an interpretation which, to say the least, was a real innovation in American history, if not the first time that it was said. Listen to what Vermont had to say:

“The people of the United States formed the Federal constitution and not the states or their legislatures and though each state is authorized to propose amendments, yet there is a wide difference between proposing amendments to the constitution and assuming or inviting a power to dictate and control the general government.”

So, the extremely brief propositions of Kentucky and the other one from Vermont really embody the whole of the controversy. The subsequent doctrine elaboration of John C. Calhoun and Daniel Webster in the 1830’s would simply embellish the arguments with analysis and historical facts and render the debate much more sophisticated, while the core of the matter was laid down in 1798. This thing about Vermont is not very well known. Even a lot of professional historians have paid no attention to it. It is really interesting to note that the position by which the Constitution was regarded as a pact founded on the States and entered into voluntarily was championed by the South, while the centralizing consolidated creed position that the American people were to be considered as one people was defended by a Northern State. Nevertheless, it would be really misleading to believe that States’ Rights was the doctrine of the Union according to the South alone. Actually, there are a lot of pamphlets that came out from New York as late as 1864 and 1865, defending the right of the South to secede. There were a lot of good New Yorkers who were on the side of secession and on the side of Constitutional government for the United States. To give you just one example, in a pamphlet on States’ Rights a respectable Northerner asserted:

“Questions which involve the reserved rights, the moral existence, the sovereignty of the States individually must be settled not by the general government, but by the States collectively. The States, the only parties to the compact which established and still the in the main so nobly sustained this Union, the States themselves are the source of political power and not the general government, a mere creation of this power for limited purposes.”

He was right on target. This man’s name was Estwick Evans, and this is from his Essay on State Rights, which was published in 1844. At the end of the book there’s a list of notables who wanted to buy it, and it seems that John C. Calhoun ordered eight copies. Before we go back to the Kentucky doctrine, let’s debunk a big myth in U.S. history, namely that Jefferson loved the Union more than anything else. For example, Peter Onuf. If you read his stuff about Jefferson there’s a clear line between Jefferson, Lincoln, FDR, and maybe Wilson. According to Onuf, these are the great Presidents, so Jefferson must be of that kind, so he loved the Union, did he not? Well, not really. Because in a letter to Madison dated August 1799, Jefferson proposed that Virginia and Kentucky should proceed side by side in a very resolute manner. Having taken note of the responses from the other states, he was now convinced that it was necessary to:

“1st. Answer the reasonings of such of the states as have ventured into the field of reason, & that of the Committee of Congress. Here they have given us all the advantage we could wish. take some notice of those states who have either not answered at all, or answered without reasoning. 2. Make a firm protestation against the principle & the precedent; and a reservation of the rights resulting to us from these palpable violations of the constitutional compact by the Federal government, and the approbation or acquiescence of the several co-states; so that we may hereafter do, what we might now rightfully do, whenever repetitions of these and other violations shall make it evident that the Federal government, disregarding the limitations of the federal compact, mean to exercise powers over us to which we have never assented. 3. Express in affectionate & conciliatory language our warm attachment to union with our sister-states, and to the instrument & principles by which we are united; that we are willing to sacrifice to this every thing except those rights of self-government the securing of which was the object of that compact; that not at all disposed to make every measure of error or wrong a cause of scission, we are willing to view with indulgence to wait with patience till those passions & delusions shall have passed over which the federal government have artfully & successfully excited to cover its own abuses & to conceal it’s designs; fully confident that the good sense of the American people and their attachment to those very rights which we are now vindicating will, before it shall be too late, rally with us round the true principles of our federal compact; but determined, were we to be disappointed in this, to sever ourselves from that union we so much value, rather than give up the rights of self-government which we have reserved, & in which alone we see liberty, safety & happiness.”[5]

That was a very clear statement. Of course, Madison was so scared that he immediately went to Monticello and tried to calm Jefferson down, and we don’t talk about the proposed secession of 1799, but otherwise it would have been possible that Virginia and Kentucky immediately left the Union. From that moment on, this was going to become one of the classic Jeffersonian topics, and in my book, I counted at least thirty to forty letters in which Jefferson very lightly talks about secession and leaving the Union. For Jefferson, freedom and self-government could not be subordinated to the Union and he placed no absolute value on Union. Compared to the extreme evil of ruthless violation of liberty, a dissolution of the compact was a lesser evil. For Jefferson, it was the rights of self-government and not the Union that were the guarantee of the safety and happiness of the people. It was clear as a Lockean that he believed that government itself was a man-made artifact to serve certain purposes. The Union was even less than a government. It was just a coalition of governments, an assemblage of State governments, so it was even lesser. If it serves the end, which is liberty, then fine, but if it does not, forget it.

During the 1820’s, Thomas Jefferson’s predictions about the possibility of maintaining a Constitutional (meaning limited) government in America grew increasingly pessimistic. A letter written a few months before his death shows him in favour of secession and even armed resistance, but only as a matter of principle, for the time had not yet arrived: “Not yet, not until the evil shall be upon us, that of living under a government of discretion.” So, he would be in favour of secession for 90% of American history. Living under a government of discretion, secession and armed resistance is certainly justified. A government of discretion was what the United States had for most of its history. A government of discretion is consolidation of power. when there are no checks and the Congress can decide upon its own powers. But the idea that the Union was just a means to an end was widely shared and was not a peculiarly Jeffersonian ideal, though Jefferson was peculiarly careless about it. One time when he was President, just after the Louisiana purchase, he said: “Well, this is probably going to split the country into two or three confederations and you know what, we’re pretty much the same people and I’ll feel that the western confederation will be my children as well as the eastern.”[6] He wrote of it as a matter-of-fact without any drama about it. The mystical doctrine of Union as a supreme end, as the absolute good to be defended at all costs, was certainly not part of the American tradition, not even to Daniel Webster. Webster begins the tradition that eventually will lead there, but there is nothing like that in Webster yet. This idea that to destroy the Union is a moral catastrophe? There’s nothing like that until the man from Springfield comes around. And so, it was really shaped in a completely novel form by Lincoln, and the idea of Lincoln (which was really metaphysical), of the existence of a single American people and its Union was gradually gaining ground. The conception that a sort of moral catastrophe would ensue from the dissolution of the union was the constant refrain of Lincoln, and when the crisis reached a peak on the 4th of July 1861, the Great Emancipator stated: “The States have their status in the Union, and they have no other legal status. If they break from this, they can only do so against law and by revolution. The Union, and not themselves separately, procured their independence and their liberty. By conquest or purchase the Union gave each of them whatever of independence and liberty it has. The Union is older than any of the States, and, in fact, it created them as States.”[7] In 1981, when Ronald Reagan was trying to talk about Federalism and what he called “New Federalism,” he said: “All of us need to be reminded that the Federal Government did not create the States; the States created the Federal Government.”[8] He thought this was just a matter-of-fact statement because supposedly he wanted to empower the States a little bit more. At the beginning it was called New Federalism. In 1982 they called it “Reaganomics” and that was it, nobody talked about New Federalism anymore. But for two years it was known as New Federalism. The history departments in this country went crazy, absolutely berserk. This one guy, Samuel Beer, said that the President was totally wrong on all accounts: “The Union was first! Don’t you know what Lincoln said?” as if Lincoln was the ultimate historical authority. Reagan was on the right track, and he, not Abraham Lincoln, was the one appealing to the tradition of Thomas Jefferson. Thank you.

[1]Jefferson to Destutt de Tracy, 26 January 1811 https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-03-02-0258

[2]Jefferson to Taylor, 4 June 1798. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-30-02-0280

[3]Jefferson to Abigail Adams, 22 July 1804. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-44-02-0122

[4]The punctuation and brackets are Jefferson’s own.

[5]Jefferson to Madison, 23 August 1799. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-31-02-0145

[6]This is, of course, a paraphrase. See Jefferson to Dr. Joseph Priestly, 29 January 1804. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-42-02-0322

[7]Lincoln’s Message to Congress, 4 July 1861. https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/july-4-1861-july-4th-message-congress

[8]Ronald Reagan, 1st Inaugural Address, 20 January, 1981. https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/inaugural-address-1981

i suppose the hypocrisy of the north came to light when they invoked states’ rights to not fight against great Britain a decade or so later. when they denied sufferage to blacks at the end of to war for southern independence. and the Hartford convention and the rest of the blather that that region has diseased this republic with. Netherlands looks nice…i like the bike paths. Google maps said the ‘treasury of virtue” was a place in mesquite texas called “PLS check cashers”. guess ill have to check them out.