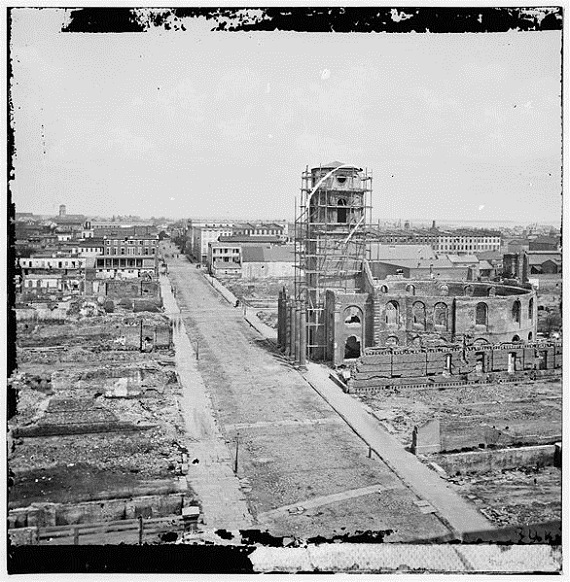

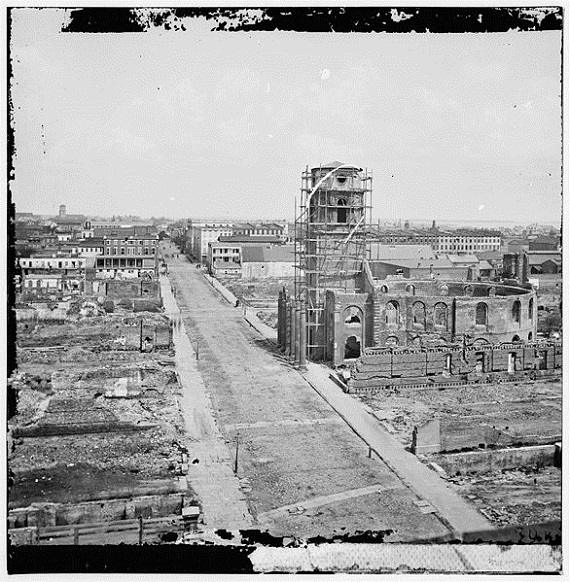

In 1865, a writer for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine described Charleston, South Carolina, contrasting her condition before the war, and after four years of siege, blockade and bombardment:

Not many years ago, Charleston sat like a queen upon the waters, her broad and beautiful bay covered with the sails of every nation, and her great export, cotton, affording employment to thousands of looms. There was no city in the South whose present was more prosperous or whose future seemed brighter. Added to its commercial advantages were those of a highly cultivated society. There was no city in the United States that enjoyed a higher reputation for intellectual culture than Charleston, and with it a refinement of taste, an elegance of manner, and a respect for high and noble lineage which made Charleston appear more like some aristocratic European city than the metropolis of an American state.

The general appearance of the city was in keeping with the historical precedents of the people. Its churches were of the old English style of building, grand and spacious, but devoid of tinsel and useless ornament. Its libraries, orphanages, and halls of public gathering were solidly constructed, well finished, and unique as specimens of architecture. Its dwellings combined elegance with comfort, simplicity with taste. The antique appearance of the city and its European character was the remark of almost everyone who visited it.

But all this is now changed. Except to an occasional blockade-runner the beautiful harbor of Charleston has been sealed for years; its fine society has been dissipated if not completely destroyed, while its noblest edifices have become a prey to the great conflagration of 1861, or have crumbled beneath the effect of the most continuous and terrific bombardment that has ever been concentrated upon a city…

Even before the war ended, Charleston was occupied by Federal troops. Uncertain as to whether General William T. Sherman’s massive army would descend on the city during his destructive march through the state, Confederate forces evacuated Charleston in mid-February 1865, and the place was left defenseless. Most of the residents also evacuated, and their unoccupied houses and other properties were left open to the depredations of the Federal troops who immediately took possession of the city.

In April 1865, after General Lee’s surrender, a large group of Northerners made a trip down the coast on the steamship Oceanus to Charleston to hold celebrations and give speeches about the war, slavery, the wickedness of the Southern “aristocracy,” and the North’s victory.

At a ceremony at Fort Sumter in which the US flag was raised over the fort again, Rev. Henry Ward Beecher gave a speech proclaiming that the sovereignty of the Federal government over the states had been settled once and for all by the war. Ignoring the fact that the Confederate States of America had had its own duly elected government, he declared under the United States flag:

Let no man misread the meaning of this unfolding flag! It says, “GOVERNMENT hath returned hither.” It proclaims in the name of vindicated government, peace and protection to loyalty; humiliations and pains to traitors. This is the flag of sovereignty. The nation, not the States, is sovereign. Restored to authority, this flag commands, not supplicates…

There may be pardon [for the Rebels], but no concession…The only condition of submission is, to submit!

For a long period Charleston was under military rule, and some houses and buildings were confiscated for the use of the occupation force and for the Freedmen’s Bureau. Eventually, most if not all of these properties were eventually restored to their former owners, but their contents were often missing, having been pillaged.

Not long after the occupation of the city, on February 28, General Order No. 8 was issued, calling on Charleston citizens to take an oath of allegiance to the United States. Those who did not take the oath would not be provided with any travel passes and would not be afforded any protection of their private property.

The Reverend Dr. Alexander W. Marshall was the rector of St. John’s Episcopal Chapel in the upper part of Charleston. The Rev. Dr. Marshall did not evacuate with the Confederate forces in February. He remained in the city, and after it was occupied, he refused to take the oath of allegiance, and also decided to omit all prayers of a political nature from his church services. A Captain H. James Weston of the 127th New York Volunteers wrote a warning to Dr. Marshall on April 15, 1865, which read in part:

It has been reported to the headquarters that you are officiating at…St. John’s Chapel, and that you have not taken the oath of allegiance, also that you have omitted the prayers for the President of the United States, which are prescribed by your church…

The next day, another Federal officer came to visit Dr. Marshall and told him that any clergyman who omitted the prayer would not be allowed to officiate in the city.

About a week later, Dr. Marshall was banished from Charleston “by command of Brig. Gen. John P. Hatch.” The clergyman’s personal property was also confiscated by the army, and a stern order was sent to his parishioners, which read in part:

In punishing the head of the congregation worshipping in St. John’s Chapel, the…general commanding desires it to be considered a warning to those who, attending the services for weeks, so far forgot their duty to their country as not to inform the military authorities of the conduct of this disloyal priest. They are also warned that they are marked persons, and any act done, or word uttered in justification of his disloyalty, will subject them to a like punishment.

In the summer of 1865 there were outbreaks of conflict between black and white residents, but also between the black and white occupying troops in Charleston. The Charleston Daily News reported in July that the city was kept in “a state of continued excitement” due to continuous “feuds existing between the white and colored troops.” A serious incident occurred that month between a New York regiment and US colored troops in which shots were fired that killed a bystander and wounded three persons, including one of the white soldiers.

Following the war, the Rev. Thomas Smyth, pastor of Second Presbyterian Church, returned to Charleston, where he found his home on Meeting Street “in a sad state.” Soon after the Confederate evacuation of Charleston, a surgeon in the Northern Army took up residence in the Smyth home and lived there for months, selling all the furniture he could before he departed.

Writing to his father, another Charleston resident who returned to the city after the war observed that the South was now under the “iron heel of despotism,” adding:

If this people had ever pictured to themselves what subjugation really meant, they never would have given up the contest while an army was left to wield a sword … I have sent you some newspapers which will convey to you better than I can the animus of the Northern people toward us. They are determined to make us drink to the dregs the cup of mortification & humiliation. Our country is ruined … We are now destined to poverty, privation, & suffering.

Such was the glorious dawn of a new era in South Carolina!