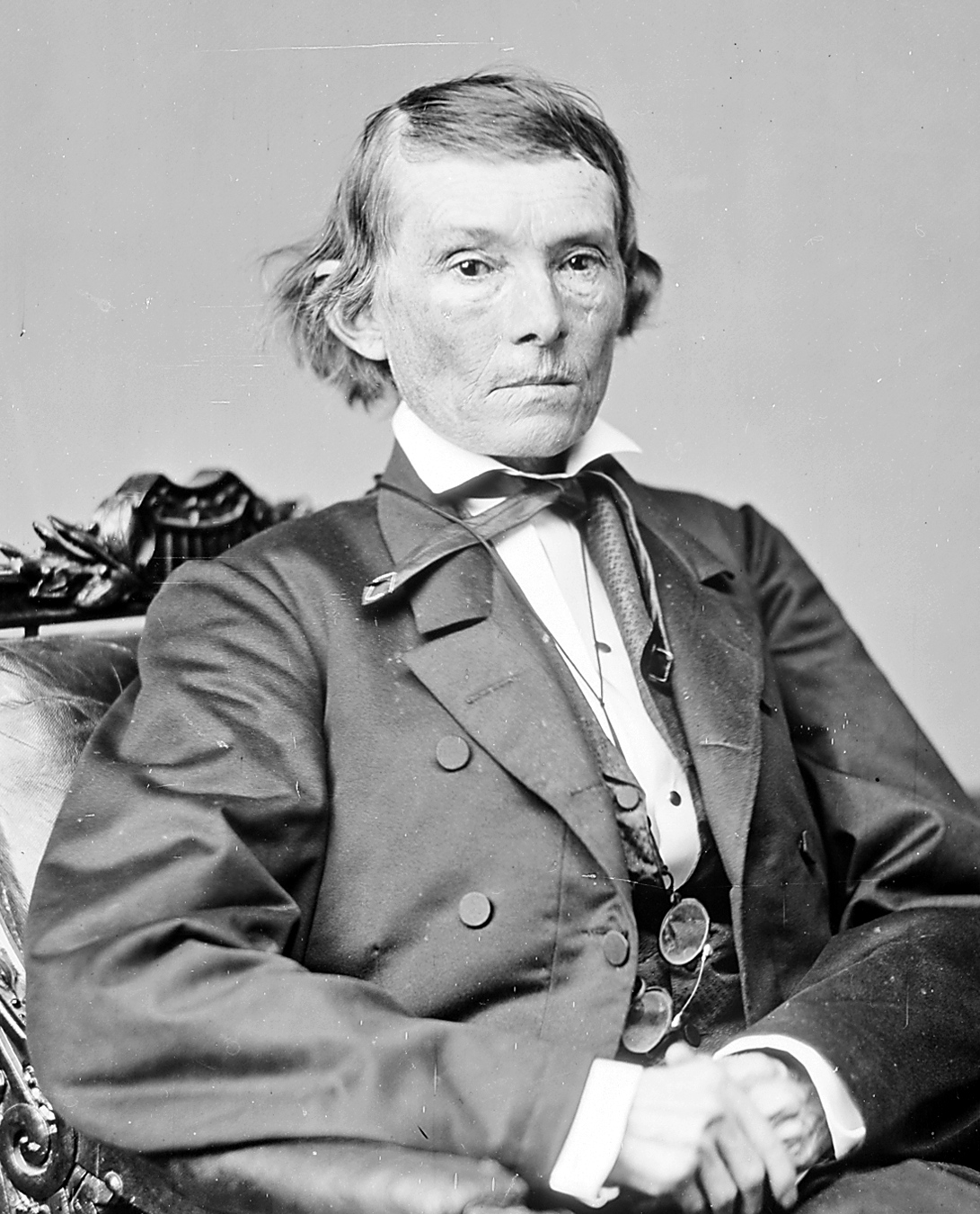

The so-called “Cornerstone Speech “delivered March 3, 1861, is one of the go-to documents of purveyors of the “Pious Cause Myth” in modern academia. This choice of title reveals their own deep-seated bias for a fabricated fashionable narrative popular among today’s academics. That narrative claims the War Against Southern independence was “all about slavery.” If you do not believe there is bias, just try to find the full text of Stephens’ speech online. You’ll have to weed through a mountain of sites that edit the speech to make it appear to be all about slavery to find that rare site that has the full text. Never mind that Stephen’s cornerstone analogy regarding slavery is buried in the middle of his speech. In the mind of modern academics, the speech must be titled in a way that emphasizes something that wasn’t a priority to Stephens when he spoke the words. A good speaker begins and ends a speech with what he considers the most important ideas he wants his audience to remember. And in the case of an impromptu speech, the speaker will usually begin with what is first and foremost on his mind. For Stephens, that was NOT slavery as a cornerstone.

Stephens’ self-proclaimed “misquoted” speech, begins with a lengthy examination of concerns regarding the old Constitution, and the correctives the Confederate Constitution provides: (1) the sectionalism of fostering certain classes to the prejudice against others is addressed; (2) the “old thorn of the tariff is forever removed from the new;” (3) sectional use of the general revenue for internal improvements is prohibited; (4) cabinet members granted input in the congressional bodies is added; (5) a one term presidency is added to prevent a reelection bid influencing crony capitalism.

Only after these priorities are covered do we come to the passage in the speech that sends a tingle down the leg of all Southern hating “pious causers.” It is the passage they lift out of all of Stephens’ previously listed contextual reasons the South seceded and attempt to make it appear to stand alone in importance. Never mind that it appears buried in the middle of the speech. Never mind that Stephens explicitly calls slavery the “immediate cause of the late rupture;” obviously meaning that while it was the most recent issue, it was certainly not the only or most important issue leading to secession. The definition of “immediate cause” is the final act in a series of provocations leading to an event. Stephens is explicitly stating that far more than just slavery was the cause of secession. Never mind that in using the cornerstone analogy, Stephens is quoting a Northern justice of the SCOTUS who used the same analogy calling slavery the cornerstone of the US Constitution (see Henry Baldwin, Assoc.SC Justice, in Johnson v. Tompkins, 1833). Never mind that Stephens’ ultimate meaning is that the Constitutional right to legal slave property was the same in both the US and CS Constitutions. Never mind all the above. What matters to pious causers is the tingle they get from a fabricated interpretation of Stephens’ speech. Somehow Stephens’ meaning must be spun to mean that the Confederacy was unique in the belief that blacks were inferior to whites and therefore subordination their natural condition. Let’s numb that tingle a bit.

Stephens’ purpose was to champion the Confederate Constitution as having been worded in such a way as to prevent attempts to circumvent its meaning. Such had been the unfortunate norm regarding the US Constitution. At the same time, he was indicating that the Confederate Constitution reflected the same principles of the old Constitution. Here is the “cornerstone” passage from Stephens’ speech:

“Our new government…Its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.”

This is the “go to” quote for the purveyors of the pious cause myth. They claim this somehow sets the CSA apart from the USA. When actually it is an example of the racist attitudes that were commonly held by most all both North and South. Lincoln is an example:

“… while they do remain together there must be a position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.”

Note Lincoln says, “while they (black and white) do remain together.” Obviously, he envisions a time when they will not “remain together.” Northern white supremacy was characterized by this vision and considered blacks an alien population. This is in stark contrast with the Southern vision which considered blacks as fellow Americans. There is in Stephens’ speech an oft overlooked passage portraying how white supremacy played out quite differently in the South compared to the North. That passage will be examined after some preliminary considerations that provide context.

In the North the inability to make slavery profitable had led to its end in most Northern States. Northern slaves were sold South, and because of Northern racism, the few remaining blacks were ostracized into segregated shanty towns; their freedom greatly restricted by Northern black codes. The lack of daily contact with blacks in the North led to an enhanced repulsion toward black flesh and a prevailing sentiment that just wanted them gone.

In the antebellum South white supremacy played out in a vastly different way, particularly given Southern slavery had evolved in a more humane manner into the 19th century. Though there was racial subordination, by sheer weight of numbers there was not segregation. The Southern people socialized, worked, worshiped, and as children played together regardless of race. This kind of human intimacy created bonds that weren’t broken but rather affirmed by abstract notions of natural rights. Those notions had led most in the South to, as Robert E. Lee said, consider slavery “a moral and political evil.” Lincoln himself admitted about Southern attitudes toward slavery that, “If it did not exist among them now, they would not introduce it.” Abolitionist societies in the South outnumbered those in the North by a four to one margin. This Southern ambition to end slavery contained two elements that Northern abolitionism lacked. Northern abolitionism called for immediate, uncompensated emancipation backed by terrorist threats. All this was motivated by an antagonism against the race of the slave and the economic/political power that slavery gave the South. Lacking was any real concern for the welfare of the slave or the Southern economy, as evidenced by the call for an immediate and unplanned emancipation. Lee saw such an “inhumane course” as doing the slaves ”great injustice in setting them free.” Northern sentiment was merely end slavery and by that end Southern power and concomitantly the presence of blacks in America. Blacks were to either “die out” having been cut off landless and penniless from the welfare of the master or be driven out of the country by a colonization that amounted to any godforsaken place but here. Were it not for the onslaught of Northern “anti-slavery,” Southern abolition sentiments would have had time to cultivate a plan for a gradual emancipation beneficial to Southern society, its economy, and the welfare of the freed slaves. But the onslaught of Northern anti-slavery propaganda, calling for slave revolts and terrorist tactics, destroyed any chance of success for Southern abolitionism. Instead, it caused the South to dig in its heels and defend slavery (as even Northern Senator Daniel Webster had admitted) to avoid economic disaster and a harmful displacing of the slaves. And it was the final determination for secession.

Southerners having grown up with black folk had no problem with the idea of living with them slave or free. The South had a larger free black population than did the North. Colonization sentiments were not near as prevalent in the South. Poems expressing familial bonds circulated decrying colonization. Jeff Davis and his brother wrote a manual teaching slave masters how to prep their slaves for eventual freedom and assimilation. Lee had rightly expressed how an immediate unplanned emancipation would cause more harm than good.

All this is the context in which we should read the often-overlooked last portion of Stephens’ Cornerstone passage:

“We hear much of the civilization and Christianization of the barbarous tribes of Africa. In my judgment, those ends will never be attained, but by first teaching them the lesson taught to Adam, that ‘in the sweat of his brow he should eat his bread,’ and teaching them to work, and feed, and clothe themselves…”

Here it can be seen that Stephens understands slavery will eventually end when the “tribes of Africa” are properly prepared. Antebellum whites often referred to blacks in America as “the tribes of Africa.” Union General Butler wrote, “I shall call on Africa to intervene” in his want of reinforcements to defend his Department of the Gulf. So, Stephens is talking about Southern slavery ending. But he realizes its end must be preceded by a preparation for living in a civilized Christian society. This is an example of the “positive good” doctrine that had long been developed in the South. As Jeff Davis had previously said, “Slavery is for its end the preparation of that race for civil liberty and social enjoyment… When the time shall arrive at which emancipation is proper, those most interested will be most anxious to effect it.”

Contrast that with Lincoln’s conviction that blacks could NEVER be assimilated into American society: “… there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races from living together on terms of social and political equality.” (Emphasis mine)

For the slaves to be able to feed and clothe themselves, they would need a place in which to do it. Stephens’ defense of slavery must be understood within this context that the Southern people found imposed on them by the North. The North was against emancipated slaves migrating North or West. How was the South to accommodate a suddenly freed, uneducated, landless, and penniless population equal to almost one half of the total population of the South, all within the limited borders of the South alone? There were vast territories to the West where, as Jefferson and Madison had prior suggested, freed slaves could be dispersed and given land. But the Republican party (as was the case in majority Northern sentiment) wanted those lands preserved for the white race alone. Those pushing for emancipation in the North wanted it to be immediate, unplanned, uncompensated, and kept within the South – the Southern economy and welfare of the blacks be damned. That is the context wherein slavery as a “positive good” can be understood. The institution served to protect blacks from Northern designs to end it. Otherwise, Southerners saw it as much a violation of natural rights as Northerners. Stephens had long believed in liberty for all. In a Texas Speech in 1845 he said:

“I am no defender of slavery in the abstract — liberty always had charms for me, and I would prefer to see all the sons and daughters of Adam’s family in the full enjoyment of all the rights set forth in the Declaration of American Independence…”

But in the antebellum South, slavery was not an abstraction. It was a problematic reality and ending it on Northern terms meant either the Darwinian “dying out” or deportation of the black folk Southerners often considered as close as family. Prior to Lincoln’s unplanned emancipation (except to the extent it could be leveraged as a “war measure”), there was no major political party that proposed emancipation simply because no one wanted to bear the economic or social cost it would demand if done with the welfare of the black folk in mind. Southerners had no choice but to defend slavery as the best of a bad historical situation given the corner they were backed into by Northern ambitions for Union-wide segregation.

The North was perfectly content to abide slavery if it was kept bottled up in the South. Northern support for the Corwin Amendment proves that to be the case. This attitude leads directly to Stephens next most poignant statement. All the North had to do if it wanted to cleanse itself of the repugnant stain of slavery was to let the South go its own way. Why was “the Union” so important that the North would go to war to keep the slave States in the Union? Stephens nails the reason, which again enlightens us as to why the South sought to secede. It was to free itself from being yoked to a section of the country that sought only to possess the Southern spoils:

“While it is a fixed principle with them (Republicans) never to allow the increase of a foot of slave territory, they seem to be equally determined not to part with an inch of the ‘accursed soil’… notwithstanding their professions of humanity, they are disinclined to give up the benefits they derive from slave labor…. The spoils is what they are after though they come from the labor of the slave…Why cannot the whole question be settled simply by…giving their consent to the separation, and a recognition of our independence?”

Stephens so called “Cornerstone Speech” is far more than merely his cornerstone analogy. The modern focus on the analogy belies Stephens’ meaning and purpose for the speech and ignores the historical context which defines the nuanced meaning of his analogy. He meant the Confederacy made explicit what was implicit in the old Constitution regarding slavery. It did so, not for the purpose of creating a “slavocracy” and “perpetuating and extending slavery’ as is so often claimed by pious causers. It did so to defend slavery as a temporary means of managing a mostly uneducated and destitute population; hoping for a day when they could be freed, dispersed, and assimilated into a Christian civilization. Until that day, slavery, in a seceded South, would protect the slaves (and the South’s socio/economic health) from the North’s inhumane ambitions to dispose of them.

“While it is a fixed principle with them (Republicans) never to allow the increase of a foot of slave territory, they seem to be equally determined not to part with an inch of the ‘accursed soil’…

Great article. But I would disagree with the above assertion by Stephens that the Republicans had fixed principles then–or NOW.

Excellent article, Mr. O’Barr.

I found this to be a most interesting, information-packed, well-argued and thoughtful article. Thank you, Mr. O’Barr!

It leaves me, though, with one wish: A link to one of those rare sites where the not-edited, full text of Alexander Stephens’ speech can be found. Already having become thoroughly disillusioned with most of the ‘mainstream,’ I just don’t feel like embarking on the (proposed) exercise of sifting through all those websites mentioned that aim to deceive the reader. Would the content of the link below pass muster? (At its very end the reporter states that it is only “a sketch of the address of Mr. Stephens [that] embraces, in his [the reporter’s] judgment, the most important points presented by the orator.”) Or can Mr. O’Barr or some reader provide a link to a better source for the full text?

https://www.owleyes.org/text/the-cornerstone-speech/read/text-of-stephenss-speech#root-94

That link is the complete speech, at least to the extent it was reported at that time. A reporting Stephens himself said was inaccurate.

I wrote an article published here on the Institute a few years ago about the same topic. I think the most glaring issue with “historians” using this speech as primary evidence of the war being about slavery, is that clearly the North held similar racial views at that time and slavery was still a US legal constitution when Stephens said this. Stephens himself later wrote from prison that his main point in that specific quote was that the status of blacks wasnt changing under the CSA Constitution.

Check our William Littleton Harris’s speech to the Georgia General Assembly regarding secession and Islam G. Harris’s speech to the Tennessee General Assembly and tell us what you conclude.

Regarding the two speeches you mention, I conclude the same as I do in Stephens’ speech. There would have been no secession and war had not the North sought political and economic dominion over the South by leveraging slavery to satisfy it own racist and political ambitions. I have read all the Secession Commissioners speeches in the past and see in them common talking points obviously coordinated and intended to turn the Northern people against the newly elected President to render him powerless to wage war against the seceded States. These speakers knew full well that Lincoln had repeatedly denied he would ever consider the equality of the white and black races within the Union. He held that for blacks to exercise their natural rights, they would first have to be deported back to “their native land.”

So why then did the Secession Commissioners attempt to paint Lincoln as an egalitarian? It was a long used political strategy (a strategy discussed in Dr. Eugene Berwanger’s book “The Frontier Against Slavery”) that Southerners had employed ever since the Republican Party had been organized. The strategy was to render that Party unpopular among its own Northern constituents by painting it as in favor of the absolute equality of the races. Such equality was anathema to the racist Northern polity, with the exception being a very small percentage of Northern abolitionists who were despised by the remainder of the North. The Southern political strategy sought to associate the Republicans and their new President with an egalitarianism detested by a racist North. The goal was to render Lincoln and his Party politically powerless among the Northern polity and therefore unable to wage war against the South. The strategy almost worked as Lincoln had to repeatedly assert his war was not about slavery but about revenue as he faced repeated calls, even from his own cabinet, to “just let the South go.”

Southerners did not desire slavery. Lincoln himself admitted this. Had the North been willing to propose a confederated effort to emancipate the slaves by compensating the slave holders and dispersing the freed slaves throughout the Union, there would have been a real prospect for ending slavery. But when faced with the segregationist North’s determination to keep all the slaves bottled up in the South, while at the same time promoting terrorist tactics inciting the slaves against the Southern people (the Tennessee Governor spends much of his speech on this topic), the South was forced to defend slavery as the best means of managing nearly half its population of destitute people within its own borders in a manner humane to the slaves and compatible with the socio/economic well being of the South. The Tennessee Governor does not champion slavery for slavery’s sake. He talks about it possibly ending if allowed in the territories when those territories formed States which then opposed slavery. But what the Governor desires as a main theme in his speech is Northern fidelity to the Constitution in regards to slavery, especially considering the Orth was seeking to leverage slavery for nothing more than political advantage and economic exploitation of the South. This is the context in which the South’s decrying of black equality and defense of slavery must be understood.

It’s funny (not really, its sad and devious) how they conveniently leave out the most important phrase “immediate cause” when arguing their point. This is the most important part of the speech and the “operative” phrase that lays out the entire reasons of secession.

The Anaconda Plan is the smoking gun. Scott maintained the relationship with the South would not change…the South would only be able to sell cotton to northern buyers (at northerner’s price), the South would have no representation, and relatively few casualties would result. The South could keep their slaves, as this was never in question. What would a naval blockade do to “free the slaves”?

The absence of Southern ship yards was a critical component…New England built the slave ships…New England would also build the naval fleet to keep the South chained to the union.

The upcoming northern transcontinental railroad would bypass the South. The Homestead Act would bring in millions of migrants to vote against Southern interests. The Morrill tariff would not be needed. The South would be hostage to yankee pricing. The Anaconda Plan was brilliant and it was sensical…but it would not settle the question of supremacy between the federal and State governments. Only total war would do that…to put the fear in the remaining States of the fate awaiting an attempted secession.

I am surprised the Anaconda Plan has not met the same fate as the Corwin Amendment…relegated to the dustbin of history for contradicting the yankee narrative.

Excellent article, thank you.

This was an incredible read. Thank you.

My problem with the speech as an “end-all” final piece of evidence showing the “true” motivation of the seceding South is more pragmatic. In my job, I represent victims of discrimination in court. The legal system is never perfect, but over now some 60 years of case law, we have a good understanding of what motivates a person to commit a discrete act at any given time. People typically act with a series of different motivations. the question then becomes what was the primary motive? Can one speech by one man on one day define why 650,000 Southerners took up arms? It is silly to think that could be so.

I went to war in 2005. We were all united by a vague, general sense of patriotism. But, out of 100 Reserve soldiers in my group, there were probably 20 who simply went to war because they had almost enough active duty time to become entitled to an active duty pension. Those 20 may have been motivated by patriotism at one point in their lives, but, in 2005, their primary motive was to serve long enough to qualify for an active duty retirement plan. “For Cause and Comrade” tells us that 59% of Southerners expressed a sense of patriotism for their service. But, even that motive appeared on perhaps just one day in one letter or in one diary entry. Motives change from day to day, week to week, year to year. The idea that the Cornerstore… err… Cornerstone speech tells us all we need to know is just silly – and even disingenuous.

Tom

It’s part of the narrative. The narrative is defined as, “the agreed upon lie”. It’s why all history books have the Crittenden Compromise but not the Corwin Amendment.

You see, the yankees voted down the Crittenden Compromise (introduced by a Southerner to protect slavery) but passed the Corwin Amendment (introduced by a yankee to protect slavery).

The one in all public indoctrination history books is the Crittenden because it shows the benevolence of the white northern people toward their black brothers held in bondage (by Whites, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Creek, etc., free blacks, Christians, non-Christians, etc.) as evidenced by its defeat…but none show the passage of the Corwin Amendment. Yankee historians (such as McPherson) deliberately go out of their way not to mention the Corwin Amendment in their writings.