Several years ago, my wife and I visited a distillery in rural Virginia that made the only whiskey in the Old Dominion that possesses legislative approval to make something called “Virginia Whiskey.” It’s a good product, though it requires the taster to accept the fact that it doesn’t taste much like Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey (I’d offer there are hints of apple therein).

Our tour guide the day we visited this distillery was a woman with an authentic Virginia accent and long hair that reached down to her behind. While explaining the aging process in a shed full of barrels, a gentleman in a cowboy hat appeared outside the shed, looking up into a blue summer sky. And he just looked. After a minute of awkward silence, the tour guide declared: “That’s Chuck. He owns the place.” Chuck nonchalantly turned to us and tipped his hat. “Howdy,” he stated matter-of-factly. Then he went back to examining that Virginia sky as if it was the most important thing in the world.

The whole experience was both hilarious and heart-warming. One of the stills was an old copper model that dated back to the Prohibition era, and has been in “continuous operation.” Think about that for a second. The still, at least back in 2016 when we visited, was held together in part by bungee coords. “A bit of redneck engineering, there,” our guide explained with a chuckle. In addition to Virginia Whiskey and white lightning, they also made whiskey flavored with various Jolly Ranchers like “Sour Apple” and “Cherry” (no, thank you!).

This little Virginia distillery will likely never compete with the behemoths in the “Bourbon Counties” of Kentucky. But what I realized that day is that whiskey is not only the province of that other commonwealth. Indeed, not far from my suburban home in Reston, Virginia is the original location of a distillery run by Abram Smith Bowman in the early twentieth century, which many now know as the well-regarded A. Smith Bowman distillery of Fredericksburg, Virginia, whose bourbons win international awards.

And 150 years before Bowman was distilling whiskey in Northern Virginia, our first president was doing it about thirty-five miles away on his Mount Vernon estate. In 1797, George Washington’s distillery began operations under the direction of his plantation manager James Anderson. At the peak of its operation, Washington’s distillery produced about 11,000 gallons of whiskey a year, one of the largest distilleries in early post-Revolutionary America, according to Bourbon expert Charles K. Cowdery in his 2004 book, Bourbon, Straight: The Uncut and Unfiltered Story of American Whiskey.

Nor are Virginia and Kentucky the only Southern locations with a long history of whiskey production. Of course, most folk know that Jack Daniel’s is not technically bourbon, but Tennessee Whiskey — though it is made in practically the same fashion as Kentucky bourbons. “Jack Daniel’s whiskey is a bourbon in every tangible sense. It looks, smells and tastes like a bourbon, and is made the same way,” writes Cowdery. But did you also know that Moore County, where the Jack Daniel’s distillery is located, is actually a dry county? Or that there is one other less well-known Tennessee whiskey called George Dickel?

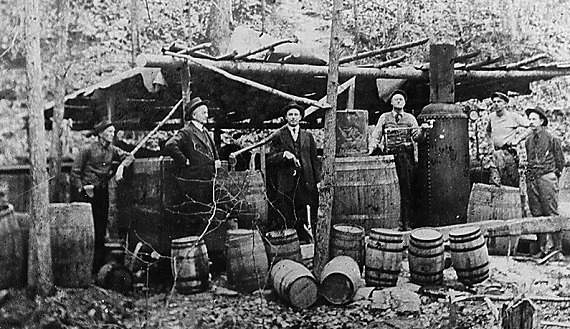

In truth, most of the states in Dixie have a stake in the history of bourbon. The Scotch-Irish distilled whiskey in the mountains of North Carolina, and some analysts suspect that even today there are more moonshiners in the Carolinas than anywhere else in the nation. They make that “good ole mountain dew.”. Alternatively, a Confederate colonel during the Civil War allegedly rejected the Confederacy’s prohibition on whiskey and distilled his own in Georgia.

Prohibition in Tennessee actually came early and stayed late, the state shutting down all of its distillers in 1911. The family then running Jack Daniel’s, the Motlows, moved the operation to St. Louis, and then to Alabama when the St. Louis distillery operation burned down. The white oak used for American whiskey barrels originates primarily in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas and Missouri from trees that are between 40 to 100 years old. Mississippi was the last state to lift Prohibition (1966!), but now has its own whiskey distillery! Indeed, most southern states, including Georgia and Florida, now have locally operated distilleries.

Many of the most iconic American whiskey cocktails are peculiarly southern. Long before the Kentucky Derby, the mint julep was recorded in early American history as a drink of the Virginia gentry, “taken by Virginians in the morning,” according to one 1803 account. Henry Clay apparently made the drink popular in Washington, D.C. in the 1850’s.

Though the sazerac is often made with cognac, the New Orleans drink is more often now concocted with American-made rye whiskey — a result of a phylloxera epidemic that devastated the vineyards of France in the late nineteenth century. The Pendennis Club, a Louisville gentlemen’s club founded in 1881, claims ownership of the old-fashioned cocktail, my personal favorite. (Let’s not speak of that sad Southern abomination, the hurricane.)

Here’s perhaps the most remarkable thing about the recent history of whiskey: when Cowdery first published his book in 2004, bourbon consumption in the United States had been declining every year since 1978. Though a great advocate and lover of bourbon, it was hard for Cowdery not to be pessimistic about the future of this distinctively American (and southern) liquor. Oh, how wrong he was. Bourbon sales have skyrocketed in the last decade-and-a-half.

In 2010, American whiskey was growing at a 2.5 percent annual rate, and super-premium brands were growing at a 16.2 percent annual rate. Five years later, American whiskey had doubled its annual growth rate, and increased its super-premium brands growth rate by about 50 percent. In other words, bourbon ain’t going nowhere.

Now, granted, as Cowdery well explains, many popular brands rely on legends and names that often have little to do with actual history. And whatever your favorite bourbon, it’s likely owned by an international conglomerate based out of somewhere like France or Japan. Check out this sad corporate chart of corporate bourbon owners for further proof of that sad fact.

Nevertheless, it’s obvious that the Southern identity of bourbon whiskey is very much integral to the brand. People drink bourbon not just because of its taste (which, granted, is heavenly), but because of its remarkable heritage, one that is thoroughly American, and peculiarly Southern American — even if its history is far more diverse than many know (Jim Beam’s story begins with a German immigrant to Kentucky named Böhm, and some early distributors were Jewish).

If there is any drink worthy of being called Southern, it must then be bourbon. Perhaps, in a way, as long as there are those who want to partake of this sweet whiskey, there remains hope that there are those outside Dixie who desperately desire the preservation of a peculiarly Southern culture and identity. And that, I’d humbly propose, is something worth drinking!

Yes, bourbon is the grand liquor of the South, but Georgia was making rum while Washington made his whiskey. Today, Georgia rum distillery is coming back for a good reason. This ain’t Bacardi It’s um good dark rum, the kind you sip on ice.