“Do fish swim in a whiskey barrel?” was the only logical response when Brandon Meeks, the Bard of Southern Arkansas, asked me to represent the new Southern journal Moonshine & Magnolias at the Upcountry Literary Festival held in Union, SC. You see, Dr. James Everett Kibler was set to receive the William “Singing Billy” Walker Award for Lifetime Achievement in Southern Letters. No chance I’m passing that up and I hadn’t even heard of Union, SC.

With high hopes and hotel booked, Mr. Patrick Seay (an Abbeville Summer School alum and Virginian Gentleman), messaged about the festival’s last-minute cancellation. However, despair had not won, Dr. Kibler invited us to Newberry, SC—to his father’s fields, to Ballylee. At first light—car loaded with books, Bourbon, and Madeira—I set forth from Franklin, TN. With festival no more, Kibler’s Upcountry Adventure commenced.

On arrival to Newberry, Patrick and I link up while noticing many Canadian license plates in the quaint downtown accommodations. Turns out, Newberry is a St. Patrick’s Day destination for a handful of Canucks. We make the rural and wooded drive out to the historic Ballylee with no expectations or itinerary. We were now on Kibler time. Amongst history and book-loving Southerners, no awkward introduction was needed. I had never met Patrick or Dr. Kibler before, but our words flowed as if reunited Army buddies, reliving battles of old.

We meander from the porch to the interior, stepping from hand-hewn plank to timeworn rug, each woven with stories older than our own. Finding sanctuary in the parlor, we settle into chairs where Rebels sat. Clocks held no dominion here. The sun held sway. I’m unfit to capture the grandeur of a room whose furnishings have outlasted empires. It’s filled with “Beloved books that famous hands have bound, Old marble heads, old pictures everywhere” as William Butler Yeats penned in “Coole Park And Ballylee.” The weight of South Carolina seemed to hang upon its walls.

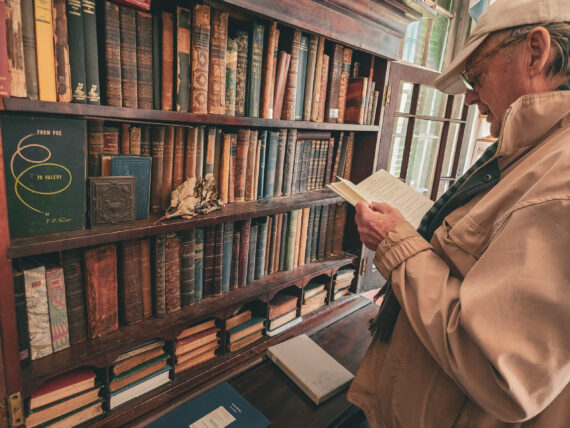

Dr. Kibler opened the bookcase with a soft creak, my eyes drawn to aged spines—each one a link in a chain stretching back through time. Selecting each volume with reverence, he regaled us with stories of the authors, inscriptions, the tales hidden within. It was a masterclass on the shelves’ denizens—Classical, English, and Irish poetry. I spoke, my voice hesitant, admitting my ignorance in the art of reciting poetry—unversed in the cadence of meter, the structure of form, and such, but I’m learning. He responded that while such knowledge had its place, the crux, the essence, lies in the reading of the words themselves. After several refills of Madeira, we moved from parlor to paradise—time to tour the land—”A spot whereon the founders lived and died / Seemed once more dear than life; ancestral trees, / Or gardens rich in memory glorified . . .” (Yeats)

Frost and deer, those twin merchants of flora’s end, came a-callin’ recently, yet beauty persisted in the gardens. Flowers, plants, and trees were honored with their given names in dual tongues, English and Latin. Patrick and I, mere observers, trailed our guide through boxwoods old enough to spot Sherman in a lineup. We ambled past crepe myrtles and colonial camellias, urged to pause because “we must smell” some bloom. Still following with pollen-coated boots, we visit Dr. Kibler’s seed shack, traverse the murmuring stream, finally circling back for a Ballylee special, toasted Chicken Salad sandwiches. Light drained from the sky, exposing day’s end.

Frost and deer, those twin merchants of flora’s end, came a-callin’ recently, yet beauty persisted in the gardens. Flowers, plants, and trees were honored with their given names in dual tongues, English and Latin. Patrick and I, mere observers, trailed our guide through boxwoods old enough to spot Sherman in a lineup. We ambled past crepe myrtles and colonial camellias, urged to pause because “we must smell” some bloom. Still following with pollen-coated boots, we visit Dr. Kibler’s seed shack, traverse the murmuring stream, finally circling back for a Ballylee special, toasted Chicken Salad sandwiches. Light drained from the sky, exposing day’s end.

Newberry County, South Carolina. Dawn breaks on Saint Patrick’s Day. Canadians, clad in the hues of verdant shamrocks, stir, soon to be awash in the emerald tides of beer and the golden embrace of Crown Royal. Patrick and I collect Dr. Kibler, setting our sights on Camden—eluding the soulless interstate, obviously. We ride and listen.

“This is where the soil turns sandy.”

“We’re about to cross the old Wagon Road.”

“Coming up on the left is a beautiful Antebellum home.”

“Down that road, so and so is buried, but you can’t go that way unless you are prepared to ford the river and a handful of streams.”

We came first to Historic Camden and the Revolutionary War Visitor Center. Dr. Kibler recognizes a familiar face, a fella he met at the previous Carolina Cup, they talk Sir Archie. Back in the car, it’s a quick drive to our true destination. We roll by Monument Park on Laurens, Boykin Park on Chesnut Street, and marvel at the historic estates. The walkways were not paved, this is horse country.

On arrival at Holly Hedge (I must name my house), we are met by our gracious hosts with the time-honored manner of the South. This storied estate, steeped in the legacy of the “Immortal 600,” also known as the William E. Johnson House, was previously owned by a horse breeder by the name of Marion duPont Scott. We get the lay of the land.

Two Cedars of Lebanon held their silent vigil amongst the elliptical garden. On their flank, a Magnolia tree, once the largest in South Carolina until scalped by Hugo. We tour the home before settling in the vast drawing room. Dr. Kibler churned our souls with two new poems penned for the now-forgotten literary festival. Transported to May 3, 1916. Padraig Pearse and Thomas MacDonagh were there. I could see them. Hear them—at least for a few trembling lines of verse. They remain alive within the tapestry of memory—at least on Mr. Kibler’s watch.

If the day ended there, I’d have been content as Paul. But it was only 1pm. Brigadier General James Chesnut, Jr. and Mary Boykin Chesnut had summoned us. We were expected at Kamschatka. Recently owned by the Buckley family before changing hands, I’d advise reading all about one of Camden’s crown jewels in Mrs. Chesnut’s diary—I assume you’re acquainted. Again, the hosts displayed unparalleled hospitality, affording us the rare privilege to wander the halls of a home rooted in the rich heritage of the South.

We tarried amid the fragrant blossoms of the Camellia garden for much of our time at Kamschatka. Dr. Kibler is the Camellia whisperer. The new owners show him a 1940s order form for Camellias from Fort Valley, Georgia. Dr. Kibler looks at me smiling and says “these are probably John Donald Wade’s Camellias. Donald Davidson probably had a hand in it too.”

Many of us know John Donald Wade as one of the Twelve Southerners of I’ll Take My Stand but Dr. Kibler knew that Mr. Wade was a true gardener. That he created his own arboretum behind his home, the Frederick-Wade House. He carefully curated a collection of shrubs and flowers from every corner of the world. Moreover, Wade played a crucial role in both the national camellia shows held in Marshallville, Georgia and the development of Dave Strother’s Camellia Gardens—where from Kamschatka’s Camellias came—now the headquarters of the American Camellia Society.

The coming storm signaled our time had come to depart. Back in the car, Mr. Kibler talks of his teaching days at Georgia, his time as a student, and when he drove his ‘62 Fairlane back and forth to Virginia while researching Faulkner. He can count on one hand how many times he’s used the a/c while driving. “I drive when it’s not hot.” His People didn’t need a/c, so he don’t need it. Back at Ballylee.

Not wanting the day to end quite yet, we return to the parlor and talk Southern magazines and journals, plus an unopened bottle of Madeira beckoned. The sun’s setting went unnoticed until the squawks of radios cease our conversation and flashlights pierced the night. For a second, I thought it was about to get all 2am History Channel-like. But something near as alien for a quiet Friday evening at Ballylee, the Newberry County Police were on the porch, hollerin’ for Mr. Kibler. Some nosy neighbor called them. Said he ain’t answered his phone in a while. Well, I guess it’s time to head home. We utter some parting words.

I count it an honor to have spent two days with the Tower on the Tyger, Dr. James Everett Kibler. A great man. A Southern man. Until next time.

I would like to have shared a glass of bourbon or mint julep with you. Having recently read “A Dairy from Dixie” by Mrs. Mary Boykin Chestnut, I would love to visit Mulberry Plantation in Camden, SC. Thanks for sharing your wonder story.