Yesterday The Washington Post published an Op-Ed by former General Stanley McChrystal in which he boasted of removing a long-displayed Robert E. Lee painting from his home to “send it on its way to a local landfill for burial.” It is but one of perhaps a dozen Post articles during the last three years disparaging Lee, Confederate monuments and Southern heritage. All condemn Lee and the Confederate soldier because in fighting to defend their homes from invaders they were also supporting a country seeking to preserve slavery.

To such critics, it is immaterial that seventy percent of Southern families did not own slaves and that Lee opposed secession. Four months before his native Virginia joined the Confederacy he wrote son Custis: “I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than dissolution of the Union. . . I am willing to sacrifice everything but honor [to preserve it.]”

The Washington Post’s March of Infamy against Southerners plays the Trump cards of slavery and racism as if they were the only two evils in the World’s history. In truth, however, the great majority of 1860 American voters did not oppose slavery in the states where it was legal. Moreover, racism was common in both the North and South. Even President Lincoln admitted in his first inaugural, “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” Eighteen months later when speaking about the problems of integration to a group of free blacks he urged them to leave America and concluded, “It is best for both [races], therefore, to be separated.”

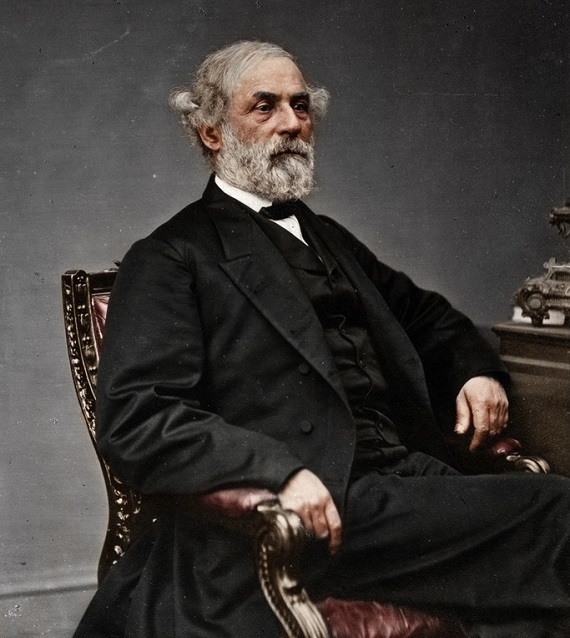

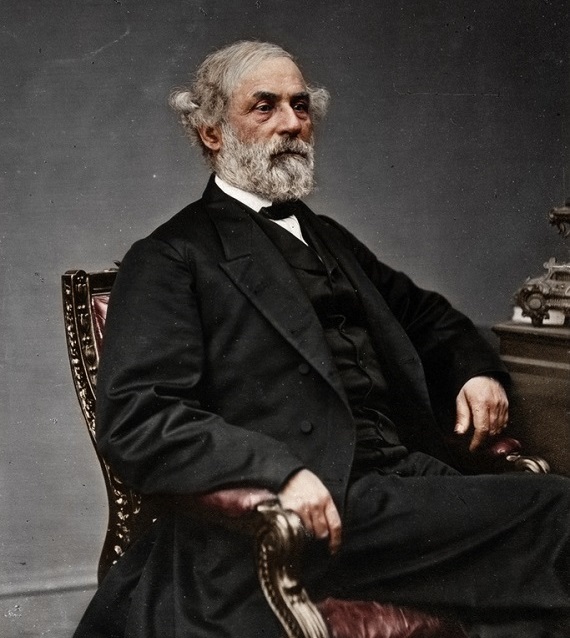

A better way to evaluate Robert E. Lee is to compare his conduct to standards that would apply to both his time and ours. In that context, consider how favorably he compares to Ulysses Grant who committed transgressions that are repugnant not only by modern standards but also by those of his time. Lee, for example, usually slept in a tent as opposed to commandeering the home of a nearby resident as was General Grant’s custom.

When his army suffered a surprise attack at Shiloh, Grant had his headquarters ten miles distant in an appropriated Southern mansion. Although saved from defeat by reinforcements from a second Union army, Grant refused to give them any credit for the ultimate victory. Afterward, he declined to pursue the defeated Confederates by claiming that their 40,000-man army actually totaled 100,000. He also lied by falsely reporting that the Rebel attack had not surprised him. He blamed subordinate Generals Lew Wallace and Benjamin Prentiss for his army’s poor performance on the first day of the two-day battle.

In contrast, less than three months after taking command of the applicable Confederate army in June 1862, Lee’s outnumbered force carried the war in the east from the doorstep of the Confederate capital at Richmond to the front porch of the Union capital at Washington. Additionally, unlike Grant who blamed others for his failures, Lee took responsibility for his most notorious defeat at Gettysburg and offered his resignation to President Jefferson Davis.

Grant’s timeless—as opposed to era-specific—immorality even sank to inhumanity during at least two battles. First, after the futile May 22nd Union attack on Vicksburg entrenchments, he left his wounded between battle lines for several days. Not until the Confederate commander suggested a truce did Grant send litter bearers to retrieve his dead and wounded. About a year later he repeated the outrage at Cold Harbor. After a failed assault, his wounded troops lay between-the-lines for two days. He took no action at all until subordinate General Meade urged it. Grant delayed relief even longer by refusing to request a conventional truce although General Meade reminded him that Lee would require it.

After the war Grant led America’s most scandal-plagued presidential administration. Next, he went on a self-aggrandizing World tour before attempting to capture a then-unprecedented third presidential term. In contrast, Lee became president of a small failing college, which he rescued financially by virtue of the donations his reputation attracted. He famously promoted the Washington & Lee Honor Code with maxims such as “we have but one rule-that every student must be a gentleman” and “as a general principle you should not force young men to do their duty but let them do it voluntarily and thereby develop their characters.”

Mr. Leigh’s books are on sale for Christmas. Check them out.