Tommie D. Boudreau, chairwoman of the African American Heritage Committee of the Galveston Historical Foundation in Galveston, Texas, recently stated that the Juneteenth national commemoration “gives an accurate picture of United States history because so much has not been shared. African Americans are the only immigrants that were forced to come to America – or the colonies. This gives people an opportunity to understand all of U.S. history.” However, she is mistaken. An accurate picture of history shows that they were not the only immigrants who were forced to come against their will. There were others who were forced to do so who were white.

In colonial times, there were two types of bondage in the original thirteen colonies, indentured servitude and chattel slavery. Indentured servitude was bondage which was limited to a specified period of time, while chattel slavery was bondage for life. There were also both whites and blacks in both kinds of bondage. All in chattel slavery and many, if not most, in indentured servitude were forced to come. In his book Emigrants in Chains: A Social History of Forced Emigration to the Americas of Felons, Destitute Children, Political and Religious Non-Conformists, Vagabonds, Beggars and Other Undesirables, 1607-1776, Peter Wilson Coldham states, “Recruitment of labour to the American tobacco plantations and to domestic service of all kinds from schoolmastering to scullery [kitchen] work was achieved in very large measure through the emptying of English jails, workhouses, brothels and houses of correction.”

By 1776, 50,000 prisoners had been sent to the colonies as indentured servants. This was also referred to as transportation. They came at a rate of over 500 per year. They constituted one in four of every emigrants to the colonies. While every ship contained hardened criminals such as murderers and thieves, the most common offense for which these prisoners were sentenced was theft of a handkerchief. There were so many poor in England that their state often led them to steal in order to obtain food. Thus, the prisons were filled with these offenders. Indentured servitude in the colonies was the means agreed upon to empty the prisons. Some of the poor who were not in prisons were persuaded to go to the colonies voluntarily as indentured servants. However, their terms were often violated and their indentures were frequently extended indefinitely. Not only men and women, but children were also persuaded to go to the colonies as indentured servants. Once a child became one, his or her indenture automatically lasted until they reached the age of 21.

White indentured servants were transported in the same way and on the same kind of ships as African slaves were. They were kept in irons and fed a meagre diet. Disease spread on these ships and killed many. Those who died were thrown overboard. Rhetta Akamatsu stated in The Irish Slaves: Slavery, Indenture and Contract Labor Among Irish Immigrants, “The cargo was carried the same way, whether black, white, indentured, or enslaved.”

This included the British colonies in the Caribbean as well as the thirteen colonies in North America. Two of the latter colonies to which many white indentured servants were sent were Virginia and Maryland. Coldham states, “Certainly from the time of the earliest English settlement in Virginia, reprieved felons worked side by side with free planters.” One of the prisons from which many went to the colonies was the infamous Newgate prison in London. It was known there as “hell above ground.” 20,000 prisoners went to the colonies from there. There is a town in Virginia which was originally named Newgate. However, its name was later changed to Centreville, the name it still bears today. A street, a shopping center, and a neighborhood there are all named Newgate. Fairfax County, where the town is located, was mostly tobacco plantations at the time, so prisoners from Newgate were undoubtedly there. New England was another destination for many of these prisoners.

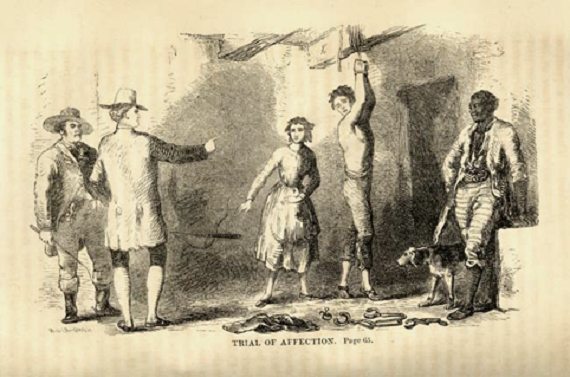

Much attention today is focused on flogging of black slaves as though flogging was some special punishment singled out only for black people. However, flogging was a standard punishment at that time. Those in prison were frequently flogged as a punishment. Newgate was well known for this practice. Flogging was also a standard punishment in the military. It was not until the 1850’s that it was abolished as a punishment in the United States military. It was also used to punish white indentured servants as well as black slaves. The conditions of both were about the same, including the food, clothing, and lodging which they were given. Those white indentured servants who had skills could fare better than the others.

As a result of the Scottish uprisings of 1715 and 1745, Scottish prisoners received transport to the colonies. In 1766, Scotland adopted the English practice of deporting its criminal elements to the colonies. In the Scottish city of Aberdeen, children were kidnapped and sent to indentured servitude in the colonies. Peter Williamson, who had himself been a kidnap victim, described it thus:

“Almost all the inhabitants of Aberdeen…knew the traffick…which was carried on in the market places, in the High Street, and in the avenues to the town in the most public manner…The trade in carrying off boys to the plantations of America and selling them there as slaves was carried on with an amazing effrontery…and by open violence. The whole neighboring country were alarmed at it. They would not allow their children to go to Aberdeen for fear of being kidnapped. When they kept them at home, emissaries were sent out by the merchants who took them by violence from their parents [and] if a child was amissing, it was immediately suspected that he was kidnapped by the Aberdeen merchants.”

The only motion picture the writer has ever seen which depicts white indentured servitude is Unconquered, which was produced and directed by Cecil B. DeMille and released in 1947. It was DeMille’s most expensive movie up to that time. In the story, Abagail Hale (portrayed by Paulette Goddard) accidentally kills a member of a press gang while defending her extremely ill brother from impressment in 1763. Her brother is also killed in the struggle and, as a result, she is found guilty of murder at the Old Bailey, the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales in London. She is sentenced to execution by hanging, but is given the option of transportation to North America to be an indentured servant for fourteen years. She chooses the latter and sails with others to be sold to Norfolk, Virginia aboard the ship Star of London. There, she is sold. The movie tells the story of her indenture. In one scene, traders attempt to sell a husband and wife separately. Abby foils the sale by pointing this out to the buyer and she is nearly flogged for doing so. In another scene, her indenture is extended for another year when a soldier accidentally spills ale she is serving on a tray, for which she is charged. She and other indentured servants are also referred to as a slaves and bondservants in the movie and indenture is referred to as slavery. In still another scene, a character named Captain Christopher Holden of the Virginia Militia (portrayed by Gary Cooper) thanks an old black slave named Jason (portrayed by Clarence Muse) for teaching him most of what he knows. The Old Bailey was a frequent scene of such sentences. Coldham writes, “In 1732 there were 502 indictments at the Old Bailey, 70 of whom were sentenced to death (some of these later acquitted), and 208 were transported.” In contrast, countless movies have been made about black slavery in the South, and with much less historical accuracy.

After 1775, the British changed the destination for transportation to Australia. In the United States, African slaves then became the cheapest form of labor. As a result, the latter then became the primary form of involuntary labor and indentured servitude declined. Many in the colonies had long objected to the influence of the criminal element being sent there.

The British had long attempted to subdue Ireland. Transportation of Irish in bondage to the colonies was a means of their subduing that island. However, unlike the English and Scots, who were only indentured servants, the Irish were not only placed in indentured servitude, but also in chattel slavery. Everyone has heard of the Middle Passage, which was the route of the slave ships which transported slaves from Africa. However, there was also an Upper Passage, which was the route from the British Isles to North America. The mortality rate among the Irish who were transported on the Upper Passage was higher than that of the African slaves on the Middle Passage. As with the English and Scots, the Irish in bondage included men, women, and children. As with all others in bondage, they were chained during their voyage.

As with the English and Scottish indentured servants, the Irish slaves and indentured servants made their way to both North America and the Caribbean. Slave breeders bred African male slaves with Irish female slaves to produce slaves which had a skin hue which made them more desirable. This was eventually stopped by the British because it cut into their African slave trade.

In 1618, a law was passed to allow both English and Irish “street children” to be enslaved and sent to Virginia. The first 100 landed there in 1619. This is something which the 1619 Project missed and needs to include. But, of course, they will not do so because if it did so that would debunk the entire false presupposition upon which the whole project is based. Another 100 children were sent in 1622, along with the reinforcements which were sent after the Indian massacre of 350 colonists that year. The agents who enslaved them were known as “spirits.” In Virginia Impartially Examined, published in 1649, they were described by William Bullock as those who “take up all the idle, lazie, simple people they can intice, such as have professed idlenesse, and will rather beg than work; who are perswaded by these Spirits they shall goe into a place where food shall drop into their mouthes; and being thus deluded, they take courage and are transported.” Richard Hofstadter wrote in America at 1750: A Social Portrait:

“The spirits, who worked for respectable merchants, were known to lure children with sweets, to seize upon the weak or gin-sodden and take them aboard ship, and to bedazzle the credulous or weak-minded by fabulous promises of an easy life in the New World. Often their victims were taken roughly in hand and, pending departure, held in imprisonment either on shipboard or in low-grade hostels or brothels.”

In the Seventeenth Century, there were more Irish slaves in the thirteen colonies than African slaves. During the last half of the century, the Irish slave population of the colonies outnumbered the entire free population. Colonel A.B. Ellis reported in Argosy, a newspaper published in British Guiana, on May 6, 1893:

“Few, but readers of old colonial State papers and records, are aware that between the years 1649-1690 a lively trade was carried out between England and the plantations, as the colonies were then called, in political prisoners…where they were sold by auction to the colonists for various terms of years, sometimes for life as slaves.”

More than 109,000 Irish slaves came to the thirteen colonies between 1700 and 1775. About 42,000 of them were Irish Catholics, the rest were Scots-Irish Protestants from the Ulster area. Irish women were sold as wives, servants, and mistresses for life, or into prostitution.

While the British transportation of Irish slaves mostly ceased in 1775, along with their transportation of white indentured servants, indentured servitude continued to be practiced in the United States after that. Article I, Section 2 of the United States Constitution recognized indentured servants, described as “those bound to Service for a Term of Years,” as being numbered among “free Persons.” While the enslavement of blacks became the predominant form of bondage thereafter, indentured servitude of whites did continue on a much lesser scale than that of black slavery at the same time. Indentured servitude continued into the Nineteenth Century.

Some indentured servants entered into a contract voluntarily, but the majority of those who are Irish did not and even had their terms of years extended for life. Even Northerners opposed to slavery, such as the Quakers, would buy indentured servants. Many of those entering into contracts consensually did so to escape extreme poverty or religious or political oppression. Indentured servants could not marry without the consent of their masters and some were forced to enter into marriages unwillingly. Many Irish were forced off their land by the British authorities if they could no longer pay for it during the Irish Potato Famine of 1845 to 1852. Many went to the work houses and to the Northern United States, and many of them as indentured servants. After “freedom,” they were faced with signs everywhere saying “No Irish Need Apply.” They faced discrimination, just as blacks did.

When the first draft for the Union army came in July 1863, the Irish saw that most of those being drafted were immigrants and they rioted in New York and Boston. Because they competed with free blacks for the lowest paying jobs, the Irish unfortunately hanged blacks in the riots. The arrival of armed Union troops from Gettysburg quelled the rioting.

Akamatsu points out that following indentured servitude, the Irish were also subjected to other forms of virtual indenture and slavery, including work on the Erie Canal. As railroad workers, the Irish were contract laborers rather than indentured servants, but they were subjected to such dangers that scores of them died. Many quarry, mine, and factory jobs were equally hazardous, and children worked there until child labor laws were passed. The description of her book on its back cover states: “If you thought that only Africans or other black races were enslaved in Barbados, West India [sic, Indies], the American Colonies and beyond, this book will open your eyes. By studying the history of the Irish, you may come to learn that slavery is not a race problem, but a human problem.”

Sources

Peter Wilson Coldham, Emigrants in Chains: A Social History of Forced Emigration to the Americas of Felons, Destitute Children, Political and Religious Non-Conformists, Vagabonds, Beggars and Other Undesirables, 1607-1776. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1992.

Rhetta Akamatsu, The Irish Slaves: Slavery, Indenture and Contract Labor Among Irish Immigrants. Middletown, DE: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2010.

Christina Sturdivant Sani, “Juneteenth and the Establishment of Federal Holidays,” NARFE Magazine, vol. 98, no. 5, June/July 2022, 26-34.

Unconquered, DVD, produced and directed by Cecil B. DeMille. Cinema Universal Classics, Universal City, CA: Universal Studios, 2007.