If “history is the essence of innumerable biographies,” as Thomas Carlyle wrote, then the historian has the advantage of witnessing past life from beginning to end. This is a solemn task. We see the spring and vigor of youth transform into the resolution and candor of manhood. The winter of life comes quickly, often suddenly. For some, the impending doom is met with clear vision, a purpose to mold their posterity. Those around them can feel this and are drawn to such men, including the historians tasked to write their story.

This Stoic sense of duty makes those who have such a purpose giants among men. John C. Calhoun was such a giant. Born on the heels of the American War for Independence and charged with protecting the Union of their fathers, this second generation of Americans understood their actions would resonate long after their death. They were reared by great men and thus became great men, and the greatest among them recognized that when Calhoun died in 1850, they had lived in his age, “the Age of Calhoun.” Historians often label this period the “Age of Jackson,” but no one left a more lasting legacy, had a more unique political philosophy, or was more visionary than Calhoun.

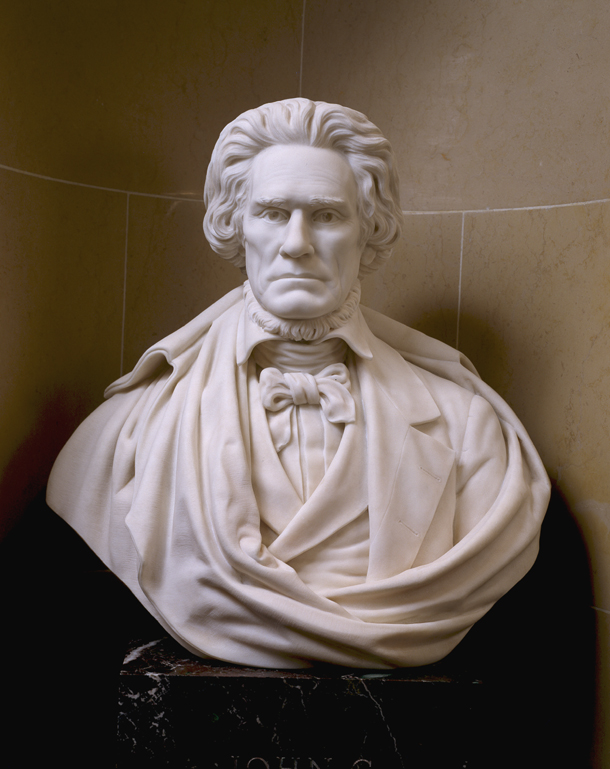

The two other members of the “Great Triumvirate,” Henry Clay of Kentucky and Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, understood Calhoun’s importance and spoke of it in their eulogies to the statesmen from Fort Hill. Both are printed below. For those who imagine Calhoun as the skeleton-like man in the famous Mathew Brady photograph, haggard by age and tuberculosis, the “Defender of Slavery” as Samuel F. Bemis labeled him, these two eulogies by Calhoun’s formidable political adversaries present a different picture. He becomes more human and less a caricature of the “evil Southerner.” Calhoun considered himself to be a Union man who cherished liberty above all else, the intellectual heir of Jefferson and Madison and the “Party of ’98.” Clay and Webster called him a patriot. It should end there.

Mr. Clay: Mr. President, prompted by my own feelings of profound regret, and by the intimations of some highly esteemed friends, I wish, in rising to second the resolutions which have been offered, and which have just been read, to add a few words to what has been so well and so justly said by the surviving colleague of the illustrious deceased.

My personal acquaintance with him, Mr. President, commenced upwards of thirty-eight years ago. We entered at the same time, together, the House of Representatives at the other end of this building. The Congress, of which we thus became members, was that amongst whose deliberations and acts was the declaration of war against the most powerful nation, as it respects us, in the world. During the preliminary discussions which arose in the preparation for that great event, as well as during those which took place when the resolution was finally adopted, no member displayed a more lively and patriotic sensibility to the wrongs which led to that momentous event than the deceased whose death we all now so much deplore. Ever active, ardent, able, no one was in advance of him in advocating the cause of his country, and denouncing the foreign injustice which compelled us to appeal to arms. Of all the Congresses with which I have had any acquaintance since my entry into the service of the Federal Government, in none, in my humble opinion, has been assembled such a galaxy of eminent and able men as were in the House of Representatives of that Congress which declared the war, and in that immediately following the peace; and, amongst that splendid constellation, none shone more bright and brilliant than the star which is now set.

It was my happiness, sir, during a large part of the life of the departed, to concur with him on all great questions of national policy. And, at a later period, when it was my fortune to differ from him as to measures of domestic policy, I had the happiness to agree with him generally as to those which concerned our foreign relations, and especially as to the preservation of the peace of the country. During the long session at which the war was declared, we were messmates, as were other distinguished members of Congress from his own patriotic State. I was afforded, by the intercourse which resulted from that fact, as well as the subsequent intimacy and intercourse which arose between us, an opportunity to form an estimate, not merely of his public, but of his private life; and no man with whom I have ever been acquainted, exceeded him in habits of temperance and regularity, and in all the freedom, frankness, and affability of social intercourse, and in all the tenderness, and respect, and affection, which he manifested towards that lady who now mourns more than any other the sad event which has just occurred.

Such, Mr. President, was the high estimate I formed of his transcendent talents, that, if at the end of his service in the executive department, under Mr. Monroe’s administration, the duties of which he performed with such signal ability, he had been called to the highest office in the Government, I should have felt perfectly assured that under his auspices, the honor, the prosperity, and the glory of our country would have been safely placed.

Sir, he has gone! No more shall we witness from yonder seat the flashes of that keen and penetrating eye of his, darting through this chamber. No more shall we be thrilled by that torrent of clear, concise, compact logic, poured out from his lips, which, if it did not always carry conviction to our judgment, always commanded our great admiration. Those eyes and those lips are closed forever!

And when, Mr. President, will that great vacancy which has been created by the event to which we are now alluding, when will it be filled by an equal amount of ability, patriotism, and devotion, to what he conceived to be the best interests of his country?

Sir, this is not the appropriate occasion, nor would I be the appropriate person to attempt a delineation of his character, or the powers of his enlightened mind. I will only say, in a few words, that he possessed an elevated genius of the highest order; that in felicity of generalization of the subjects of which his mind treated, I have seen him surpassed by no one ; and the charm and captivating influence of his colloquial powers have been felt by all who have conversed with him. I was his senior, Mr. President, in years & in nothing else. According to the course of nature, I ought to have preceded him. It has been decreed otherwise ; but I know that I shall linger here only a short time and shall soon follow him.

And how brief, how short is the period of human existence allotted even to the youngest amongst us! Sir, ought we not to profit by the contemplation of this melancholy occasion? Ought we not to draw from it the conclusion how unwise it is to indulge in the acerbity of unbridled debate? How unwise to yield ourselves to the sway of the animosities of party feeling? How wrong it is to indulge in those unhappy and hot strifes which too often exasperate our feelings and mislead our judgments in the discharge of the high and responsible duties which we are called to perform ? How unbecoming, if not presumptuous, it is in us, who are the tenants of an hour in this earthly abode, to wrestle and struggle together with a violence which would not be justifiable if it were our perpetual home!

In conclusion, sir, while I beg leave to express my cordial sympathies and sentiments of the deepest condolence towards all who stand in near relation to him, I trust we shall all be instructed by the eminent virtues and merits of his exalted character, and be taught by his bright example to fulfill our great public duties by the lights of our own judgment and the dictates of our own consciences, as he did, according to his honest and best comprehension of those duties, faithfully and to the last.

Mr. Webster: I hope the Senate will indulge me in adding a very few words to what has been said. My apology for this presumption is the very long acquaintance which has subsisted between Mr. Calhoun and myself. We are of the same age. I made my first entrance into the House of Representatives in May, 1813, and there found Mr. Calhoun. He had already been in that body for two or three years. I found him then an active and efficient member of the assembly to which he belonged, taking a decided part, and exercising a decided influence, in all its deliberations.

From that day to the day of his death, amidst all the strifes of party and politics, there has subsisted between us, always, and without interruption, a great degree of personal kindness.

Differing widely on many great questions respecting the institutions and government of the country, those differences never interrupted our personal and social intercourse. I have been present at most of the distinguished instances of the exhibition of his talents in debate. I have always heard him with pleasure, often with much instruction, not unfrequently with the highest degree of admiration.

Mr. Calhoun was calculated to be a leader in whatsoever association of political friends he was thrown. He was a man of undoubted genius, and of commanding talent. All the country and all the world admit that. His mind was both perceptive and vigorous. It was clear, quick, and strong.

Sir, the eloquence of Mr. Calhoun, or the manner of his exhibition of his sentiments in public bodies, was part of his intellectual character. It grew out of the qualities of his mind. It was plain, strong, terse, condensed, concise; sometimes impassioned — still always severe. Rejecting ornament, not often seeking far for illustration, his power consisted in the plainness of his propositions, in the closeness of his logic, and in the earnestness and energy of his manner. These are the qualities, as I think, which have enabled him through such a long course of years to speak often, and yet always command attention. His demeanor as a Senator is known to us all & is appreciated, venerated by us all. No man was more respectful to others; no man carried himself with greater decorum, no man with superior dignity. I think there is not one of us but felt when he last addressed us from his seat in the Senate, his form still erect, with a voice by no means indicating such a degree of physical weakness as did, in fact, possess him, with clear tones, and an impressive, and, I may say, an imposing manner, who did not feel that he might imagine that we saw before us a Senator of Rome, when Rome survived.

Sir, I have not in public nor in private life, known a more assiduous person in the discharge of his appropriate duties. I have known no man who wasted less of life in what is called recreation, or employed less of it in any pursuits not connected with the immediate discharge of his duty. He seemed to have no recreation but the pleasure of conversation with his friends. Out of the chambers of Congress, he was either devoting himself to the acquisition of knowledge pertaining to the immediate subject of the duty before him, or else he was indulging in those social interviews in which he so much delighted.

My honorable friend from Kentucky has spoken in just terms of his colloquial talents. They certainly were singular and eminent. There was a charm in his conversation not often found. He delighted, especially, in conversation and intercourse with young men. I suppose that there has been no man among us who had more winning manners, in such an intercourse and conversation, with men comparatively young, than Mr. Calhoun. I believe one great power of his character, in general, was his conversational talent. I believe it is that, as well as a consciousness of his high integrity, and the greatest reverence for his intellect and ability, that has made him so endeared an object to the people of the State to which he belonged.

Mr. President, he had the basis, the indispensable basis, of all high character; and that was, unspotted integrity & unimpeached honor and character. If he had aspirations, they were high, and honorable, and noble. There was nothing groveling, or low, or meanly selfish, that came near the head or the heart of Mr. Calhoun. Firm in his purpose, perfectly patriotic and honest, as I am sure he was, in the principles that he espoused, and in the measures that he defended, aside from that large regard for that species of distinction that conducted him to eminent stations for the benefit of the republic, I do not believe he had a selfish motive, or selfish feeling.

However, sir, he may have differed from others of us in his political opinions, or his political principles, those principles and those opinions will now descend to posterity under the sanction of a great name. He has lived long enough, he has done enough, and he has done it so well, so successfully, so honorably, as to connect himself for all time with the records of his country. He is now a historical character. Those of us who have known him here, will find that he has left upon our minds and our hearts a strong and lasting impression of his person, his character, and his public performances, which, while we live, will never be obliterated. We shall hereafter, I am sure, indulge in it as a grateful recollection that we have lived in his age, that we have been his contemporaries, that we have seen him, and heard him, and known him. We shall delight to speak of him to those who are rising up to fill our places. And, when the time shall come when we ourselves shall go, one after another, in succession, to our graves, we shall carry with us a deep sense of his genius and character, his honor and integrity, his amiable deportment in private life, and the purity of his exalted patriotism.