Xenophon in his Memorabilia (II.i.21–34) cites Prodicus’ account of Herakles (L., Hercules), “passing from boyhood to youth’s estate,” at a crossroads. He went to a quiet place to consider his course of life, when he was visited by two goddesses—Hēdonē (Pleasure) and Aretē (Virtue). “The one was fair to see and of high bearing; and her limbs were adorned with purity, her eyes with modesty; sober was her figure, and her robe was white. The other was plump and soft, with high feeding. Her face was made up to heighten its natural white and pink, her figure to exaggerate her height. Open-eyed was she; and dressed so as to disclose all her charms.”

Hēdonē quickly approached the muscular demigod, the son of Zeus and the moral Alkemene, and showered him with promises. “Make me your friend; follow me, and I will lead you along the pleasantest and easiest road. You shall taste all the sweets of life; and hardship you shall never know. First, of wars and worries you shall not think, but shall ever be considering what choice food or drink you can find, what sight or sound will delight you, what touch or perfume; what tender love can give you most joy, what bed the softest slumbers; and how to come by all these pleasures with least trouble.” In short, Hercules, choosing Hēdonē, would to enjoy the fruit of others’ labors.

Aretē then demurely approached and said:

I will not deceive you by a pleasant prelude. … For of all things good and fair, the gods give nothing to man without toil and effort. If you want the favour of the gods, you must worship the gods: if you desire the love of friends, you must do good to your friends: if you covet honor from a city, you must aid that city: if you are fain to win the admiration of all Greece for virtue, you must strive to do good to Greece: if you want land to yield you fruits in abundance, you must cultivate that land: if you are resolved to get wealth from flocks, you must care for those flocks: if you essay to grow great through war and want power to liberate your friends and subdue your foes, you must learn the arts of war from those who know them and must practice their right use: and if you want your body to be strong, you must accustom your body to be the servant of your mind, and train it with toil and sweat.

Thinking through the dilemma, Heracles, so goes the mythical tradition, chose the path of virtue and endeared himself, through his heavy, amaranthine sufferings, to the gods and to men.

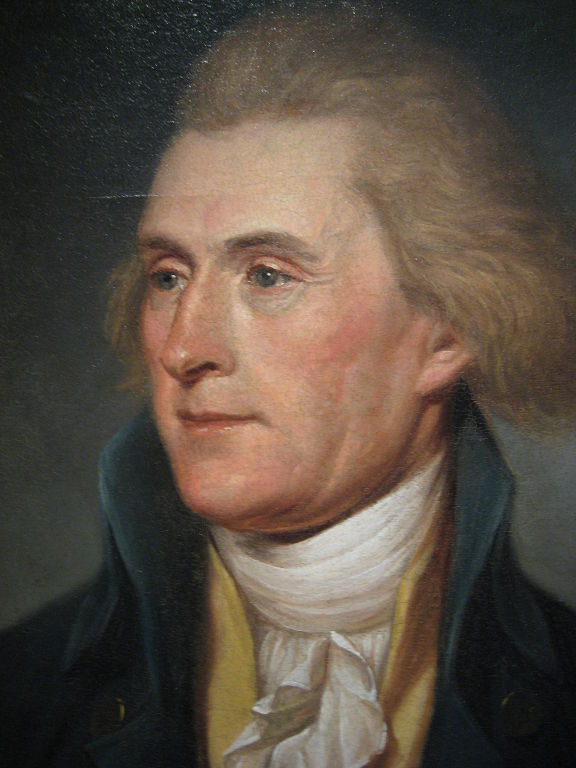

Jefferson was, of course, no Hercules. Jefferson was lanky and cerebral, whereas Herakles tended to overcome or endure through brute physicality (the exception being the Augean Stables). Yet Jefferson, like Hercules, also mentioned an early life crossroads at which he sat. To grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph (24 Nov. 1808), he writes movingly of two paths that he, at a kairotic moment at the age of 14 and upon the death of his father, faced. I quote this extraordinary passage in toto:

I had the good fortune to become acquainted very early with some characters of very high standing, and to feel the incessant wish that I could ever become what they were. Under temptations and difficulties, I would ask myself what would Dr. Small, Mr. Wythe, Peyton Randolph do in this situation? What course in it will insure me their approbation? I am certain that this mode of deciding on my conduct, tended more to correctness than any reasoning powers I possessed. Knowing the even and dignified line they pursued, I could never doubt for a moment which of two courses would be in character for them. Whereas, seeking the same object through a process of moral reasoning, and with the jaundiced eye of youth, I should often have erred. From the circumstances of my position, I was often thrown into the society of horse racers, card players, fox hunters, scientific and professional men, and of dignified men; and many a time have I asked myself, in the enthusiastic moment of the death of a fox, the victory of a favorite horse, the issue of a question eloquently argued at the bar, or in the great council of the nation, well, which of these kinds of reputation should I prefer? That of a horse jockey? a fox hunter? an orator? or the honest advocate of my country’s rights? Be assured, my dear Jefferson, that these little returns into ourselves, this self-catechising habit, is not trifling nor useless, but leads to the prudent selection and steady pursuits of what is right.

The passage, oft quoted, has never been given due consideration. I have in Thomas Jefferson, Moralist, drawn out the moral implications of this much neglected passage, but here I would like to focus on something different.

Jefferson acknowledges, as did Prodicus’ Hercules, that there are two passages in life—that of pleasure seeking (e.g., horse racing, fox hunting, and card playing) and that of gainful occupation (e.g., science, law, and politics). Like Hercules, Jefferson chose the “dignified line”—that of being of service to his fellow men and perhaps even to deity. His choice of the dignified line, he confesses, was decided by reflection on what his moral heroes—Small, Randolph, and Wythe—would have done had they been in the same situation.

Recognition of two distinct paths in life make seem like small beer; it is not. Jefferson’s recollection is of a weighty dilemma that occurred to him relatively early in life, at 14, and just after the death of this father, Peter Jefferson. Perusal of the writings for memoirs other significant early American figures show no similar early life dilemma. It was typical of those of a similar age at the time to think about girls, to have a little fun, and perhaps to worry a little about a career, though many adolescents merely followed in the footsteps of their fathers. For Jefferson, the death of his father left him in a moral quandary. He would self-catechize throughout his life and always place moral considerations ahead of all others. He was preeminently a moralist and only derivatively a rationalist, but that is the subject for another essay.