As I’ve mentioned before, my hometown is Tuskegee, Alabama, which is not famous because of me. However, some of the many things for which Tuskegee is known include the Tuskegee Airmen, the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, the Commodores and Lionel Richie, Tuskegee Institute (which is now Tuskegee University), Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver. Besides me, one of the other things for which Tuskegee is not known (but should be) was for showing how people – not laws – could make integration a successful working reality.

I once heard a famous speaker describe an occasion where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. explained the difference between the South and the rest of the country. According to the speaker, King said that in the South, although groups and organizations of different people might not get along very well with each other, the individual people inside the different groups often do. And in the rest of the country, the situation is exactly reversed. I will never be smart enough to say it any better than that, because his analogy absolutely encapsulates the South. I’ve turned that description over and over in my head many times, and it is flawless. It is the very dichotomy that defines the South, and it is the heart of the frustration that enlightened Yankees feel when all their sermons about everyone else’s diversity never seems to work out in their own backyards. They talk a damn good game of diversity, but they don’t have a clue as to how to practice it, and it kills them that Southerners are so natural about it.

I was born and raised in Alabama, and I’ve lived and visited all over the country, and King’s description is beautifully perfect. In the enlightened areas of the Northeast, the Midwest, and the Far West, the groups of people technically “get along” with each other, but the face-to-face man-to-man interactions of the individuals within the organizations do not exist. They don’t know each other at all. They don’t live together, they don’t work together, and they don’t know anything about each other. In my opinion, this easily explains why King chose Alabama as the focal point of the Civil Rights struggle. He didn’t select Alabama because Alabama was the most backwards place in the country and the place in need of the most help and change (which is, unfortunately, what everybody assumes). No, King chose Alabama because the people of Alabama offered him the most promise for success. The people, not the institutions, were the key to Alabama. He knew that in order for Civil Rights to actually work, it had to be more than just a skeletal outline of dry laws. Civil Rights would have to contain a heart and a soul, and that’s why the people of the South – black and white together – were so important. Who cares if the laws are on the books or not? If the people can’t figure out a way on their own to make it work, it will never stick. King was right.

During a family gathering/class reunion earlier this summer, one of my sisters and my mother were talking about the days of integration and desegregation in Alabama in the early 1960’s. Being born in 1960, I was too young to remember a lot of it, but my oldest sister is 10 years older, and was in the generation of kids that were used as pawns to fight those social battles. She told me a lot of things about her childhood that I’d never heard before. Tuskegee, Alabama, was a small, quiet town with a close-knit community until it became an unwilling pawn in the never-ending political battle between the Kennedys and Governor George Wallace.

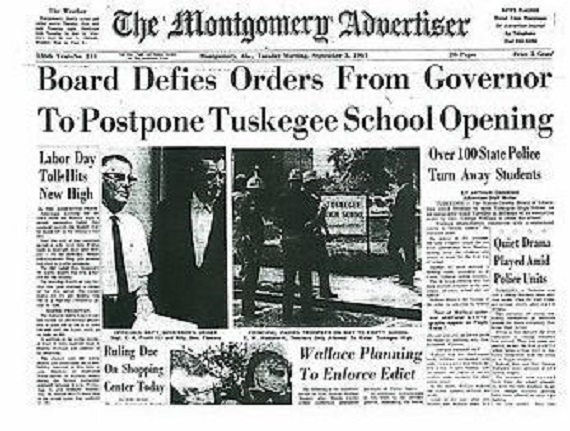

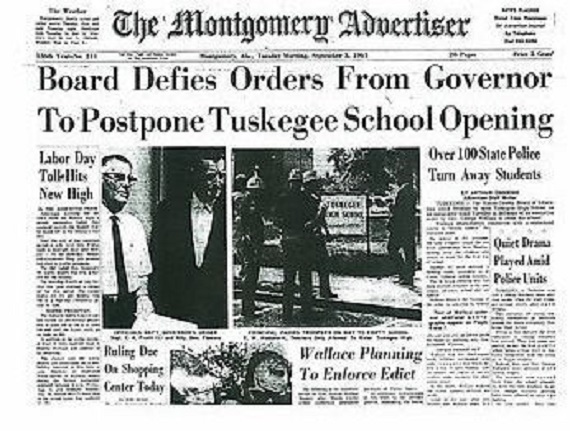

When my sister was starting the 7th grade in 1963, Federal Judge Frank Johnson ordered the integration of the public schools in four municipalities in Alabama – Birmingham, Mobile, Huntsville, and our own tiny, sleepy little Tuskegee. Governor Wallace had been using segregation as his political battle cry, and he vowed to prevent the desegregation of Alabama’s schools. However, since Wallace did not have the legal authority to challenge the federal court’s ruling, he tried a different tactic. He simply closed the schools as part of his authority as President of the State Board of Education. If the school was not open for business, then it couldn’t be integrated. Since the daily operation of each public school was an obligation of state government, Gov. Wallace was in his rights to close the school, but it was a silly, petty, spiteful move without any thought to the families or the communities that would be affected. Birmingham, Mobile, and Huntsville soldiered on. Tuskegee was devastated.

My two sisters and brother found themselves on that morning in September with no schools to attend. My sister said that they all got up to go to school on the first day, and found all the roads blocked by armed State Troopers preventing anyone from reaching the school. Since we lived on one of the streets behind Tuskegee High School, the State Troopers were parked right at our house and camped out in our front yard. The black students who would have integrated Tuskegee Public Schools that day simply turned around and returned to their former all-black schools out in the rural parts of the county. However, the white students had no alternative school in town to attend. They had nowhere else to go. When Wallace shut down the school, he took away their only means of attending classes in Tuskegee.

All that summer prior to the impending integration, city groups, councils, and committees held meetings to chart a course that would allow the city to absorb the hullabaloo without being torn apart. Tuskegee High School’s white students held their own meetings with black students from nearby schools to plan assemblies and activities to address students concerns and hopefully alleviate the anxiety about the changes they were facing. Several student and community groups met throughout the summer to talk about what was going to occur to help ease the integration process into something productive, manageable, and non-violent. Although the students were youthfully naive, they knew it would be up to them to make it work. The impending iron boot of Federal law might have been poised to stomp out Tuskegee’s guts, but the town became proactive and the people within the community worked hard to make sure it didn’t turn into a mess. Also, anyone who knows anything about Tuskegee’s demographics and history knows how utterly ridiculous it would be to imply that whites in Tuskegee could simply find a way to “avoid contact” with blacks and remain segregated. Although I’ve never actually seen the official census data, I’ve always heard that the ratio of blacks to whites in Tuskegee in 1960 was 11 to 1. Without question, Tuskegee was the most unique small town in Alabama because it was already de-facto integrated. White-owned businesses depended on a desegregated clientele long before desegregation was fashionable. They didn’t need laws to force them into getting along with each other – it was already a social and economic obligation. To suggest that whites in Tuskegee were seeking white-only enclaves is to display total ignorance about the actuality of daily life in Tuskegee.

However, with the intervention of Gov. Wallace and the State Troopers, all of those plans of cooperation were thrown out the window. The presence of the troopers and the armed siege that engulfed Tuskegee turned the slight apprehension from that summer into panic and anger. No one knew what course to take. After enduring the troopers that were camped out in people’s yards and their presence dominating the town, they were suddenly gone as quickly as they appeared. President Kennedy stepped in and ordered Wallace to remove the troopers and allow the school to open. On a Monday morning in late-September, Tuskegee High School finally and quietly re-opened. Integration went forward in Tuskegee without a single national headline or newsreel teaser because most of the “bugs” had already been worked out. Although I was too young to remember those fateful events, I very clearly remember watching on TV the riots in Boston during the late 70’s protesting forced integrated school busing and thinking to myself, “Where have you people been for the past 15 years? We’ve had integrated busing down here in Alabama throughout my entire school career.” Of course, today I know exactly where those enlightened Yankees had been for all those years. They were too busy telling everybody else how to get along instead of learning it for themselves.