On April 24, 1863—-just three months after the cruel and retaliatory Emancipation Proclamation–Lincoln issued an order drafted by Columbia University law professor Francis Lieber that codified the generally accepted universal standards of warfare, particularly as it related to the lives and property of civilians. Among the actions it deemed to be criminal and prohibited were the “wanton devastation of a district,” “infliction of suffering” on civilians, “murder of private citizens,” “unnecessary or revengeful destruction of life,” and “all wanton violence…all robbery, all pillage or sacking…all rape, wounding, maiming, or killing.”

It is true that it also provided, in its articles 14 and 15, a slippery provision called “military necessity,” under which “destruction…of armed enemies” and of “other persons whose destruction is incidentally unavoidable” was completely permissible, and allowed “the appropriation of whatever an enemy’s country affords” by the conquering army. But it is clear that the overall intent of the Code was to rein in atrocities by the Union Army, particularly toward civilians.

The Union Army in the preceding years of the war had generally observed such principles as the Lieber Code set out, although there had been many instances of victorious troops that, as one general said of the Union troops in Baton Rouge, “regard pillaging not only right in itself but a soldierly accomplishment” and there were a few instances of renegade generals who led their troops into wholesale devastation of civilian targets.

But when the new element to the war became the cause of eliminating slavery, a certain moral fervor was cast upon the troops, or a good many of them at least, that eventually added a kind of John-Brown-like zealotry to the Union cause. It was not that there was any particular passion to see black people freed but rather to abolish slavery itself, an easily condemnable institution that was the economic and political pillar of the hated Southerners. That is why, within just a few months of the Emancipation Proclamation, a number of commanders in the field, despite the recently released Lieber Code, felt sanctioned to unleash the equivalent of what in the 20th century came to be called “total war”—a war upon civilians and their property in the South, with attendant looting, murder, arson, and rape, and neither women, children, the old and infirm, or oftentimes even blacks, were spared.

And with the sanction of General Henry Hallek, General-in-Chief of the Union Army, who let it be known on March 31, 1863—-a slim month after the Lieber Code was issued to the troops– that Union generals should now enlarge the conflict in ways that General Halleck could say that spring changed “the character of the war” and allowed, “no peace but that which is forced by the sword.”

To which Grant wrote responded:

Rebellion has assumed that shape now that it can only terminate

by the complete subjugation of the South….It is our duty to weaken the enemy, by destroying their means of subsistence, withdrawing their means of cultivating their fields, and in every other way possible.

It was the following year—150 years ago—that the Union Army was able to start this “complete subjugation,” largely through the work of General William Sherman, who totally shredded the Lieber Code and trod it under the feet of his three powerful armies. He went through Mississippi, then Tennessee, then into Georgia, where he destroyed Atlanta in September and then moved south to Savannah, where he contemplated his march northward through South Carolina.

As Sherman wrote to Hallek once he settled in Savannah, “The truth is the whole army is burning with an insatiable desire to wreck vengeance upon South Carolina. I almost tremble at her fate, but feel that she deserves all that seems in store for her.”

So the subsequent campaign was, unbelievably, even fiercer than the Georgia one, for after all South Carolina had been the first to secede and first to fire a shot (though in answer to a Union invasion of Charleston Harbor); a reporter for a Northern newspaper wrote: “As for wholesale burning, pillage, devastation, committed in South Carolina, magnify all I have said of Georgia fifty-fold, and then throw in an occasional murder.”

The army, still 60,000 strong, marched north through the state in two swaths, one going up the coast toward Charleston and the larger unit going northwest to Columbia, the capital, where the vengeance it planned was indeed insatiable, and on into North Carolina. Resistance was meager, there being not more than a few thousand able-bodied soldiers left in the whole state. Destruction of property, military and civilian, through the countryside was nonetheless total. A Union captain wrote that “the destruction of houses, barns, mills, etc. was almost universal,” and a Sherman aide testified that” a majority of the Cities, towns, villages and country houses have been burnt to the ground,” many of which were never rebuilt even after the war. A Union major, George Nichols, wrote this condemnation: “Aside from the destruction of military things, there were destructions overwhelming, overleaping the present generation…agriculture, commerce, cannot be revived in our day. Day by day our legions of armed men surged over the land, over a region forty miles wide, burning everything we could not take away.” At least 35 towns and cities in South Carolina, and perhaps a hundred or more plantations, were torched and destroyed.

A Union Captain George Pepper classified the devastation:

First, deliberate and systematic robbery for the sake of gain. Thousands of soldiers have gathered by violence hundreds of dollars each, some of them thousands, by sheer robbery…. This robbery extends to other valuables in addition to money. Plate and silver spoons, silk dresses, elegant articles of the toilet, pistols, indeed whatever the soldier can take away and hopes to sell….A second form of devastation…consisted in the wanton destruction of property which they could not use or carry away….This robbery and wanton waste were specially trying to the people, not only because contrary to right and the laws of war [you see, they did know what was right], but because it completed their utter and almost hopeless impoverishment. The depth of their losses and present want can hardly be overstated.

The devastation of Barnwell, South Carolina, 80 miles northwest of Savannah, seems to have been typical. South Carolina literary light William Gilmore Simms would write:

On what plea was the picturesque village of Barnwell destroyed? We had no army there for its defense: no issue of strength in its neighborhood had excited the passions of its combatants. Yet it was plundered—and nearly all burned to the ground; and this, too, where the town was occupied by women and children only. So, too, the fate of Blackville, Graham, Bamberg, Buford’s Bridge, Lexington, etc., all hamlets of most modest character, where no resistance was offered—where no fighting took place—where there was no provocation of liquor even, and where the only exercise of heroism was at the expense of women, infancy, and feebleness.

A Mrs. Aldrich remembered the sight of Barnwell after the Union army left:

All the public buildings were destroyed. The fine brick Courthouse, with most of the stores, laid level with the ground, and many private residences with only the chimneys standing like grim sentinels; the Masonic Hall in ashes. I had always believed that the archives, jewels and sacred emblems of the Order were so reverenced by Masons everywhere…that those wearing the “Blue” would guard the temple of their brothers in “Gray.” Not so, however: Nothing in South Carolina was held sacred.

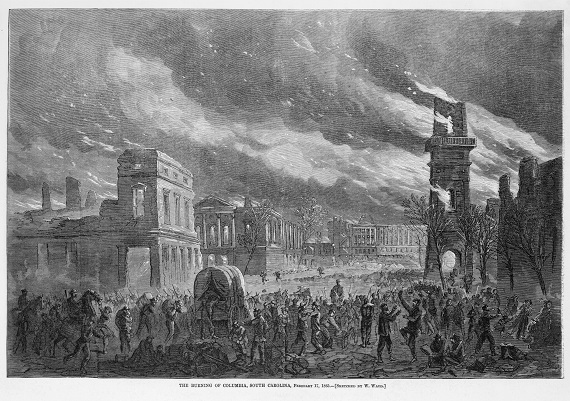

All this was exceeded by Sherman’s obliteration of Columbia, which his army reached in-mid February 1865, and though the city surrendered without resistance Sherman set his troops loose to pillage and burn the hated center of secession, the soldiers “infuriated, cursing, screaming, exulting in their work,” according to one account. It goes on: “The drunken devils roamed about, setting fire to every house the flames seemed likely to spare…They would enter houses and in the presence of helpless women and children, pour turpentine on the beds and set them on fire.” By midnight “the whole town was wrapped in one huge blaze.”

Simms draws these pictures:

Hardly had the troops reached the head of Main street, when the first work of pillage began. Stores were broken open within the first hour after their arrival, and gold, silver, jewels and liquor eagerly sought….Among the first fires at evening was one about dark, which broke out in a filthy purlieu of low houses of wood on Gervais street, occupied mostly as brothels….Almost at the same time a body of the soldiers scattered over the eastern outskirts of the city and fired the dwellings….There were then some twenty fires in full blast, in as many different quarters…thus enveloping in flames almost every section of the devoted city….By midnight, Main street, from its northern to its southern extremity, was a solid wall of fire….And while these scenes were at their worst—while the flames were at their highest and most extensively ranging—groups might be seen at the several corners of the streets, drinking, roaring, reveling—while the fiddle and accordion were playing their popular airs among them.

And this was not the happenstantial work of a few renegade soldiers. This was what Sherman intended, giving loose to his army’s “insatiable desire.” In his memoirs he bluntly bragged that he had “utterly ruined Columbia.”

On March 3, Sherman’s troops captured the little city of Florence, in northern South Carolina, on their way to North Carolina. A Union officer, noting the army’s path, wrote: “The sufferings which the people will have to undergo will be most intense. We have left on the wide strip of country we have passed over no provisions which will go any distance in supporting the people.” On that same day, 350 miles north, Abraham Lincoln addressed a crowd from the steps of the capitol after his second inauguration. He promised to continue the war being fought “with malice toward none; with charity for all.” With malice toward none.

The next month, in Virginia, at General Grant’s headquarters, Sherman regaled Lincoln with reports on his successful marches through the South. He recalled in his memoirs that the President was particularly keen on his stories of the foragers in uniform and their pillaging and burning as they wreaked their vengeance on the enemy, or at least the enemy’s countryside and civilian population.

Sherman’s campaign, along with those of General Philip Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley (where he followed out Grant’s instructions to leave it “a barren waste”) and Grant’s in Virginia against Lee’s declining forces, had their desired effect. The Confederacy’s back was effectively broken, and with burnt-out fields, decimated livestock, devastated populations, and no slave labor under control it was left without means to recover and regroup. On April 9 Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox and within a month or so other Confederate commands followed suit.

As was said in another context, they made a desert and called it peace.

In the end, after four years of brutal war, the bloodiest in American history, the first to be fought on civilian soil, the South had lost at least 50,000 civilians, by the commonly reckoned account, mostly to disease and starvation but not a few to weaponry. Another 426,000 soldiers died, at a bare minimum, maybe 30 per cent of white males of military age in the South, and some 320,000 were wounded; suicide and mental illness amounted to what scholar Diane Miller Sommerville has called “a virtual epidemic of emotional and psychiatric trauma among Confederate soldiers and veterans.” The South suffered an estimated $3.3 billion in property damage, including railroads, bridges (one third said to be destroyed), banks, factories, warehouses, and homes. And some 3.5 million slaves, reckoned in 1860 to be worth $3.5 billion in 1860 dollars, were taken from their owners, what historian R. R. Palmer has called “an annihilation of individual property rights without parallel…in the history of the modern world,” no people anywhere having “to face such a total and overwhelming loss of property values as the slave-owners of the American South.”

If the estimate of the total cost of the war is accurate—put at $6.6 billion by the Encyclopedia of the Confederacy, not counting he slaves—then the South would have paid the much greater part of that, and yet with an infrastructure demolished in most places it had no real means of recovery. All of its prewar railroads were destroyed (except for the Louisville & Nashville, which the Union Army used), and even as late as 1880 the South had only a third of its prewar mileage. Its entire economy, almost entirely based on plantation agriculture, was destroyed, and even where farming was taken up again it was mostly done by sharecroppers now. The North, which expanded its manufacturing and railroad sectors threefold during the war years, hardly suffered at all and was able in the war’s aftermath to build a prosperous infrastructure for the future.

But the toll on the South was far greater even than the huge number of people lost and the devastated landscape. For the South was a conquered country, whipped, disheartened, demoralized, beaten in soul and spirit, its social fabric in tatters, its customs and traditions trampled on, its institutions gutted, and its very civilization shaken to its roots. The Nation magazine, a pro-Union publication that started this year, wrote in September: “There has probably never been a people, since the Gauls, so thoroughly beaten in war as the Southerners have been….This generation is certainly as the mercy of its conqueror, and incapable of offering the least opposition to its mandates.”

Thanks to the complete and utter disregard of the Lieber Code, an unprecedented disaster, and one that would leave scars and wounds for at least a century and a half.