L. Q. C. LAMAR TO THE VICKSBURG COMMITTEE

OXFORD, Miss., Dec. 5, 1870. To Col. William H. McCardle, and others, Committee, etc.,

Vicksburg, Miss.

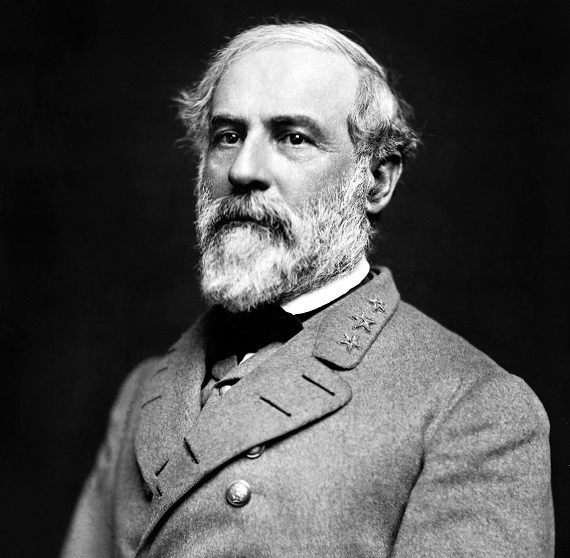

GENTLEMEN: When, on the occasion of Gen. Lee’s death, I received your invitation to deliver an address on the 19th of January next, at the city of Vicksburg, the strongest impulses prompted me to an immediate and cordial acceptance. Subsequent reflection, however, showed me that I could not so regulate my engagements as to permit the making of a positive promise to be present on that proudly mournful occasion.

If my long delay in giving you a final answer seems strange, consider it as due to my anxious desire to avoid the necessity of relinquishing such an opportunity of giving voice to the emotions which fill my soul when contemplating the life that has just closed amid the tears of a nation’s sorrow.

While a career illuminated by every accomplishment of the soldier and scholar, as well as the highest feelings of the patriot and gentleman, is beyond all eulogy, it is nevertheless our duty and delight to make every effort to give some expression to our sense of its grandeur, just as it behooves us to make every preparation for eternity, although eternity is beyond the grasp of our comprehension.

The day of his death will be the anniversary of the South’s great sorrow. But it was not his darkest day. I was at Appomattox when the flag which had been borne in triumph upon his many battlefields was torn from his loving and reluctant grasp. After the terms of capitulation had been arranged, chance brought him to the spot where my tent was pitched.

I had seen him often before. On one occasion, especially, I remember how he appeared in a consultation of leading men, where, amid the greatest perturbations, his mind seemed to repose in majestic poise and serenity. Again, I saw him immediately after one of his grand battles, while the light of victory shone upon his brow.

But never shall I forget how completely his wonted composure was overthrown in this last sad interview. Every lineament of his grand face writhed, and the big tears fell from his eyes as he spoke of the anguish of the scene he had just witnessed. And yet his whole presence breathed the hero still. A consciousness of a great calamity to be greatly endured gave to his face the grandeur of victory as well as the mournfulness of death; and when he exclaimed, “It is worse than death!” I could easily see how he would have welcomed the grave for himself and all that he loved, could it have only averted his country’s awful woe. Ah, my countrymen! well may you weep over his grave, for there lies one whose heart broke in the very tension of its love for you and your country.

Between the characters of Washington and Lee, Dr. Palmer, in a recent address, draws a parallel which is no less true than it is eloquent and suggestive. The points of resemblance between them were indeed many and striking. Both were Southerners; both were slaveholders, both, by inclination as well as inheritance, were planters; both possessed in an eminent degree those qualities which ennoble and invigorate the Southern character; and both were inspired by a heroic devotion to liberty and right. But here the parallel ends. As the orbs of heaven are alike in brilliancy and grandeur and divinity, while yet “one star differeth from another star in glory,” so were the wonderful virtues which were common to the souls of both these men strangely diverse in their manifestations. Each was a man sui generis. Purely original in their characters, neither ever thought of forming his own nature on any prototype or of establishing in himself an archetype for others. This indifference to what men generally seek with greatest assiduity -conformity to some recognized model-naturally produced peculiarities to some extent alike, but to a larger extent unlike.

For instance, both were of unflecked social purity. Washington, however, was cold and austere in his nature. Inaccessible to men, formal to women, no warmth of social enjoyment or rational pleasure ever thawed the frigid dignity which enveloped him. Lee, on the contrary, was affectionate and genial. Cheerful without levity, cordial but not obtrusive, he enlivened the hours of relaxation with a humor almost sportive in its fancy, while the moments of sorrow were comforted by the sympathies of a loving heart.

The soul of Washington was pure and cold, like an Alpine glacier; the soul of Lee was limpid and warm, like the waters of the Indian ocean.

Both were just, magnanimous, and modest. Washington, however, was born with a love for command, and a yearning after it. He fawned upon no one, and he scorned to act the part of a demagogue; but those whom he suspected of disputing his leadership he denounced with fierce and vehement wrath. Even those who beheld him for the first time intuitively recognized in him a master; for the intensity of his will, and its calm self-assertion, placed him in authority over men as naturally as the sweep of pinion and the strong grasp of talons place the eagle in the kingship of birds.

To Lee self-assertion was a thing unknown. His growth into universal favor and honor was the result of a slowly dawning consciousness in the popular mind of his retiring merit and transcendent excellence, of that affinity which silently draws together great men and great places when a nation is convulsed.

Washington wooed glory like a proud, noble, and exacting lover, and won her. Lee sought not glory; he turned away from her. But glory sought him, and overtook him, and threw her everlasting halo around him; while he, all unconscious of his immortality, was following after duty.

Both were born to command, and both led the armies of a mighty struggle. But Washington, though in a great measure he began and conducted to a successful end a great revolution, has never had accorded to him by history the title of a great military genius. From a want of opportunity or some other cause it was not permitted to him to make those brilliant manifestations of military capacity which startle the world into the acknowledgment of that attribute.

Lee, by his splendid generalship and grand battles, wrung homage from the lips of his bitterest enemies, and inspired his armies, always inferior to the enemy in numbers and appointments, to endure sacrifices and perform prodigies of valor which excited the wonder and admiration of the world.

Washington was a man of strictest integrity and sublime virtue and there is much in his writings which evinces a profound sense of a Divine Providence in human affairs; but he could not, I apprehend, be called a pious man.

Lee, with the same majestic morality, with the same imposing virtues of truthfulness, courage, and justice, blended the sweet and tender graces of a holy heart and a Christian life.

Both were patriots, but Washington stood before the world an avowed revolutionist. The movement he led was an acknowledged insurrection against established authority. He drew his sword to sever the connection between colonies and their parent country, between subjects and their legitimate sovereign a connection that rested on historic foundation and on undisputed legal rights.

But there was not in Lee or his cause one single element of revolution or rebellion. Conservative in his nature and education and associations, unswerving in his loyalty to the power which for him was paramount to all others, the cause in defence of which he drew his sword was founded upon historic rights, constitutional law, public morality, and the inviolable right of free and sovereign States, many of whose constitutions were established and in peaceful operation while that of the United States lay unthought of in the far-off years of futurity.

It has been said that “General Lee’s memory belongs to no particular section; that his fame is to be, not that of the Confederate chieftain, but of the great American soldier.” I must confess that I do not believe that this sentiment finds any genuine response in the hearts of our people. True, the war has closed; and it is high time that the evil passions which it aroused should be hushed. Would to God that the memories of its outrages and atrocities could be banished forever from the minds of men! And if the victorious North would afford to the defeated people of the South the benefits of the Union and constitution, in whose name the desolations of war were visited upon them, and permit them to enjoy, in the Union, real union, concord, amity, and security from oppression, the Southern people would be prompt to bury all the animosities of the war, to remember only its glories, and to regard the glories won by each people as the common property of the American nation. But into this common heritage they will never consent to put the name and fame of Robert E. Lee. They will ever feel that they cannot, and ought not, to surrender him to America. They cannot forget that after the war had closed, after the South had surrendered her arms and submitted to the Constitution of the United States upon the Northern interpretation of it, after slavery had been abolished and secession pronounced null and void in every Southern State, after the integrity of the Union was established and recognized in every county, town, house, and hovel in the desolate land, Robert E. Lee and his people were, to the day of his death, branded as rebels and proscribed as traitors to America. By far the greatest military genius on the American continent, his love for his country obliged him to withdraw from the American army and throw himself into the breach of its colossal invasion; one of the most superb gentlemen in America, he was proscribed from the higher employments of American society, and compelled to earn his living in the seclusion of a Southern college; possessed of the highest order of statesmanship known to America, he was deprived of the ordinary rights of American citizenship; and thus his eyes closed in death on America. Purity of heart, fervor of religion, might of intellect, and splendor of genius, were rendered hateful in the sight of those who arrogate to themselves exclusively the title of the American people, by the single sin of love for the South, the land of his birth.

He has already taken his place in history; not as an American, but as a Southern patriot and martyr, of whom America was not worthy. Every thought of his brain, every pulsation of his heart, every fold and fibre of his being, were Southern. Not a drop but of pure Virginia blood flowed in his veins. Virginian, Southern, Confederate, secession, from crown to sole, he had no aspiration in common with America as America now is, or sympathy with her works as they now are; and from the day on which his venerable State seceded from the American Union there was not an hour when he would not have gladly offered up life and all that life holds dear on the altar of Southern rights against American oppression.

It has been said that “Gen. Lee belongs to civilization.” Aye, he belongs to civilization! But let it not be forgotten for such will be the record of impartial history—that it was the Southern type of civilization which produced him! And now that a sublime self-immolation has fixed him on the topmost pinnacle of fame, let his immortal image look down forever upon the ages, the perfect representative of the mighty struggle, the glorious purpose, and the long-sustained moral principle of the heroic race from which he sprung. Thanking you, gentlemen, for the kindness which prompted your invitation, I am, Your friend and obedient servant,

L. Q. C. LAMAR.

A wonderful compilation of significant American history and our two most revered leaders. Thank you for sharing it, and I am passing it on to a new generation. Sincerely,