The whole 20th century was a horrible time for the friends of tradition: the mild rule of Europe’s Christian monarchs – Habsburgs, Romanovs, and others – was replaced by the ruthless Communists and later the despotism of the European Union, amongst other totalitarian ‘isms’; Mao overthrew Confucius in China; the natural rhythms of the agrarian life in many places of the world were overwhelmed and driven out by the increasingly artificial and fast-paced urban life (if one may call it that) centered around the new holy trinity of ‘science, technology, and industry’, in Wendell Berry’s words; total war destroyed much else; etc.

World War II, however, seems to have been a watershed in this process of the destruction of tradition, for after that war the naming of generations begins, something unheard of before. The list goes something like this:

The Baby Boomers (born 1946-1964)

Invented: free love.

Known for: benefiting from free university education, a prosperous jobs market and robust economic growth.

Big on: telling each other that if you remember the 1960s, you weren’t really there.

Generation X (born 1965-1981)

Invented: irony, McJobs and disaffected slackerism.

Known for: their diet of MTV, rave culture and indie films.

Big on: reminiscing about 1988’s second summer of love.

Millennials (born 1982-1995)

Invented: avocados and overly elaborate coffee orders.

Known for: making “hipster” a dirty word and sending selfies mainstream.

Big on: blaming Boomers for dismantling the concept of free university education, homeownership and jobs for life.

Generation Z (born 1996-2016)

Invented: the ability to hold a conversation and simultaneously scroll through their phones.

Known for: being globally connected and politically anxious.

Big on: experimenting with gender and sexual spectrums.

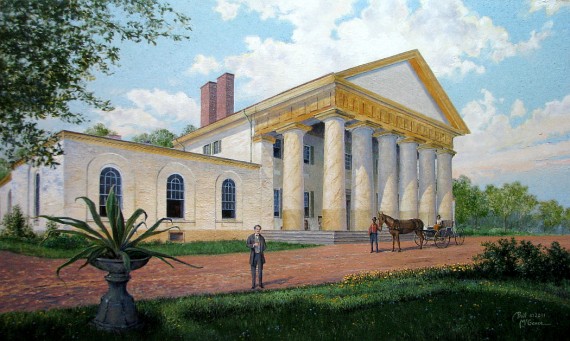

Here, then, is one more way to undermine the continuation of Southern identity: not simply by way of indoctrination with new ideologies and false histories, which is pernicious enough, but by creating entirely new tribes that Southerners must belong to (and identify first and foremost with), based on whether or not they fall within an arbitrary set of years. So now a child born in Dixie will no longer belong to the unbroken continuum of Robert Beverley, Jr., William G. Simms, and Marion Montgomery – he will belong to some artificial little band consisting of Johnny Carson, Paul McCartney, and Richard Dawson; and so on for each generation.

Before World War II, however, before the great upheavals and dislocations caused by Modernity, each generation generally lived as those before them had: There was no need to name each bairn-team anew, for the world they knew was the same one their parents and great-great-grandparents had known. But now through the wonders of modern technological advancements, we are recreating the world every few years through the alchemy of never-ending creative destruction.

Southerners and other nations which have held on to a few shreds of tradition must be especially wary while living in this order (or disorder) of things. The assumption seems to have been that whatever is good in Southern life will automatically be passed on to the next generation, as though it were part of the genetic code, or that the schools and colleges, whether public or private, or other institutions, would impart it in some way to the young. Such assumptions are false.

Handing on a tradition takes effort. A lot of effort. And no complicated treatises need to be read to confirm that. A little reading from the Holy Scriptures will do just fine. Archpriest Josiah Trenham writes of tradition in the New Testament context:

The teaching of the Apostles is itself called ‘tradition’ in the New Testament. A word commonly used for this is the Greek word paradosis (παράδοσις) meaning teachings or commandments that are handed over or down. “Now we command you, brethren, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you keep aloof from every brother who leads an unruly life and not according to the tradition which you received from us” (2 Thess. 3:6). . . . Again St. Paul wrote to the Corinthians [I Cor. 15:3] using the verbal form of the word ‘tradition’: “Now I traditioned/handed on to you as of first importance what I also received…”

—Rock and Sand: An Orthodox Appraisal of the Protestant Reformers and Their Teachings, Columbia, Missouri, Newrome Press, 2015, p. 266

‘Traditioning’ is a process, one that can be corrupted by those holding other views. It can also be undermined by a lack of care from those who are to pass it on: This is a lesson from the Old Testament regarding the handing on of tradition. For example, we find this in Deut. 6:6-12: ‘And these words, which I command thee this day, shall be in thine heart: And thou shalt teach them diligently unto thy children, and shalt talk of them when thou sittest in thine house, and when thou walkest by the way, and when thou liest down, and when thou risest up. And thou shalt bind them for a sign upon thine hand, and they shall be as frontlets between thine eyes. And thou shalt write them upon the posts of thy house, and on thy gates. And it shall be, when the LORD thy God shall have brought thee into the land which he sware unto thy fathers, to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, to give thee great and goodly cities, which thou buildedst not, And houses full of all good things, which thou filledst not, and wells digged, which thou diggedst not, vineyards and olive trees, which thou plantedst not; when thou shalt have eaten and be full; Then beware lest thou forget the LORD, which brought thee forth out of the land of Egypt, from the house of bondage’ (copied from https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/k/kjv/kjv-idx?type=DIV1&byte=741530). This injunction to the Israelites is repeated in Deut. 11:18-20.

Likewise, those who are taught the tradition bear the responsibility of learning it by heart. Father Josiah Trenham again relates a passage from the New Testament, writing, ‘St. Paul praised the Corinthians [I Cor. 11:2] for adhering to the Church’s tradition, “Now I praise you because you remember me in everything, and hold firmly to the traditions, just as I delivered them to you” (Rock and Sand, p. 266)’. While in the Old Testament book of Jeremiah we find this verse (6:16): ‘Thus saith the LORD, Stand ye in the ways, and see, and ask for the old paths, where is the good way, and walk therein, and ye shall find rest for your souls. But they said, We will not walk therein’ (copied from https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/k/kjv/kjv-idx?type=DIV1&byte=2808522).

At one time, Southerners were generally mindful of their duty towards their tradition. Nathaniel Macon, to give but one example, once said, ‘Why depart from the good old way which has kept us in quiet, peace, and harmony—everyone living under his own vine and fig tree, and none to make him afraid? Why leave the road of experience, which has satisfied us all and made us all happy, to take this new way . . . of which we have no experience?’ (Quoted in Robert Calhoon, Evangelicals and Conservatives in the Early South, 1740-1861, Columbia, S. Car., U of SC Press, 1988, p. 169)

But due to the march of Progress mentioned above, this has not been the practice of the South of late. Whether it is the act of passing on her traditions to the younger generations or the act of learning those traditions by the latter, there has been much carelessness and heedlessness. The Southern tradition has been slowly dying, and now there are few living links from whom one may properly learn it. More and more, Southrons must turn to books as their teachers. Thankfully, there is an abundance of good ones, spanning the centuries of Dixie’s life as well as a range of genres.

Nevertheless, tradition is strong meat. It has a deep power latent within it. That power will draw people unto itself. But it must be approached in the proper way, or it will leave them frightened and bewildered, a truth that is illustrated well in the following story:

The previous story about the punishment for blasphemy of the Austrian official which had taken place before the eyes of many people reminded the young man of a song his Grandfather had sung with his gusle a long time ago, by the fireplace of their old family home in the hills above Nikshich. He could see the fireplace with its pothooks and a hole in the ceiling above it which served as a vent for the smoke which led to the attic. From the attic the smoke would escape through cracks between the bricks on all sides of the house, so that from afar it always looked as though it was on fire. He remembered how the fire in the hearth was never allowed to go out, for among the Montenegrins, a hearth without a fire meant the end of one’s family tree, the death of a family. He remembered how all the men of the family would sit in a circle around his grandfather, while the women, headed by his grandmother, sat or stood according to their age and rank behind the men. The children would run about while the adults sat in front of the fire in solemn silence, listening to grandfather’s gusle with the utmost reverence and awe. Grandfather looked so powerful and so mysterious in the golden-red reflection of the fire whose sparks sometimes flew dangerously close to his face. Even the older people, let alone the children, were afraid of those sparks, but Grandfather’s composure was unshaken, so engrossed was he in his singing. He remembered how, when the sparks flew into the air he would run as far away as possible from the fire and crouch in the half shadow of the wall. Soon, frightened by the flickering shadows on the wall, he would creep back closer to the fire, closer to his grandfather, and press his cheek into the dark wood of the little oak table beside Grandfather’s stool.

–Protopresbyter Radomir Nikchevich and Vesna Nikchevich, The Mystery of the Wonder-Worker of Ostrog, trans. Ana Smylyanich, Svetigora, 2003, p. 90

As with the Serbian boy and his Grandfather’s singing, so with the South and her tradition: It must be approached with filial piety, for it is the sum of all the ordinary and extraordinary works of so many of our forebears. If the South can do this, the Southern tradition may well survive; the bane that is generational naming will come to a quick end; and we will be Southerners, and only Southerners, down through the ages.