“Tell us about when you were little” was the oft repeated request of two lovely wee girls, my grandchildren and now comes the request that I put it down in writing. Viewed from their own childhood of peace and plenty mine seemed a strange one.

Impressed by mother’s courage

Looking backward to that long ago childhood, the thing that impresses me most was the undaunted courage of my mother. My father, Dr. Reden Nauflet Parker, was a surgeon in the Confederate Army and her four brothers were in the same army. She was left with two little children to care for and get along as best she could. No man to shield and protect her.

In these “Piping Times of Peace” when the Yankees are welcome to our sunny southern climate it seems almost unreal with what dread, “The Yankees are coming” once filled our hearts. The Yankees came and were soon opening trunks, dresser drawers, everything searching for valuables. They did not find any, for several nights before and alone, my mother had gone secretly and dug a hole in the henhouse, where she buried what little gold and silver money she had left, her jewelry and silver tableware. She pulled a box in which a hen was sitting over this place so that the newly upturned dirt would not be noticed. That hen sat undisturbed over the gold and silver mine, and I’ve heard my mother say was the only one she had left when the Yankees were gone.

I loved pets

I always loved pets — dogs, cats, birds, a motherless kid, a cripple chicken. At this time I had a most unusual one, a pig whose mother had died. With the help of Amies, my faithful attendant, I fed this pig with scraps from the table. It became a fat shote and followed me about as a dog, or “Mary’s Little Lamb,” much to the annoyance of my Mother. I suppose in the excitement of the evening, Bettie my pig was forgotten. We slept in our clothes that night. At least I did, I don’t suppose my Mother slept.

Never occurred to me they would kill my pig

Early next morning I missed my pig. She could not be found. I went about calling her until one of the Negroes said, “I ‘spect them Yankees done got yo’ pig.” There was an encampment just back of our garden. It never occurred to me that the Yankees would kill my pretty fat pet pig. So I marched off, and invaded that Yankee Camp unafraid — a small girl between four and five years old, re-enforced in the rear — considerably in the rear — by a Negro girl Annes, about thirteen. I demanded my pig. I had marched upon a camp of officers, for I have a vague memory of eppaletes upon the shoulders of a tall man who got up, came to me and said, “Little girl we haven’t got your pig.” He must have seen the distress in my face. Perhaps there was the thought of a little girl in a far northern state.

Why I would not kiss a Yankee!

Anyway he picked me up in his arms and said, “Won’t you kiss me?” My reply came quickly, “Why I would not kiss a Yankee!” How those men laughed and how quickly one small rebel retreated vanquished by a laugh! Children do hate to be laughed at when serious. My Mother was greatly concerned when she found I had gone adventuring into a Yankee Camp and I’m afraid she scolded Annes.

Annes bought me chicken

I suppose when my Mother could no longer stand the loneliness — my little sister had died — she went to either my Father’s mother or her own mother. It was at the home of my Father’s mother that I vaguely remember an attack of scarlet fever. About the only thing I remember was a piece of fried chicken, a drumstick brought to me, I suppose by Annes.

I do not know why I was left alone with Annes, nor how she got the drumstick, whether she slipped it from the kitchen or whether it was the choice portion of her own dinner. In these days of child specialists and careful diets, it seems strange that a child seriously sick should have been given fried chicken even by a Negro. Fortunately my throat was too sore for me to eat it when I tried. My mother or my grandmother came in and Annes and the drumstick were sent away.

After I had fully recovered we went to the home of my Mother’s mother. There were no disinfectants in the South at that time save sunshine and hot water. My advent into this grandmother’s home was followed by an outbreak of scarlet fever. They said it was carried in my woolen clothing. One little Negro girl whose mother was dead and who was being brought up in the house by my aunts, died. I felt very sad looking at Viney on her little white bed, and in a way responsible for her death.

I suppose there must have been a scarcity of food in those days when the war was nearing a close. I do not remember, but I am sure there could have been no well balanced rations.

Even as a child I felt the gloom that was taking the place of enthusiasm. One of my uncles was dead, another wounded and one a prisoner. It was a common thing to see men with an arm or a leg missing and I remember only too well one man who hobbled about on stumps of legs, both having been removed above his knees.

I had bright hopes for Christmas

Christmas Eve came and bright hopes with it. Although my Mother and young aunt tried to impress me with the fact that there would be nothing. I still believed in Santa Claus, and even after any experience, with the pet pig, I did not believe that the Yankees would kill Santa Claus, and that someway those reindeer would get him by the Yankees. So I hung my stocking by the fireplace, I suppose my Mother and aunt thought that the hurt of the little home knit stocking hanging limp and empty would be too much.

They called upon their utmost resources and I found it full on Christmas morning — molasses, peanut candy, ginger cakes, parched peanuts and right in the toe a beautifully painted egg. The latter having been beautified from a box of water colors, left from other days. How happy I was! Going out in the yard I called across the way to another little girl all the wonderful things I had received. Annes said, “I wouldn’t be hollering about ’em if I was you, sounds like you are so proud of ’em.” Poor ‘Annes! She could remember other Christmas mornings when molasses candy, gingercake and a hardboiled egg were not things to be proud of. How careful those Negroes were of us. How we must “mind our manners,” but what little snobs they tried to make us. “You is quality”. How often the Negroes used that word “quality” in just that way.

Heard the word surrender for the first time

Time passed. One spring morning I had started to school when my Father (You will not I wrote Father and Mother with capital letters. I assure you that is correct. They were due capitals) said, “Do not go to school today.” He was talking to several men and I heard the word “surrender” for the first time. I wanted to know what it was all about, and learned the war was over. I could not understand the looks of sadness, for it seemed to me that they should be rejoicing. I do not know why my father was at home, whether on leave of absence, or because doctors at home as well as in the army were needed, for besides the women and children and Negroes there were now many disabled men.

I was soon to understand the sadness for in a short time Annes left us, persuaded away, my Mother said, but nothing could soften the blow! I was bewildered, how was I to get on without Annes! I think she went to another town.

How I was glad to see Annes

After a year, perhaps longer, she came back to see us and brought me a beautiful toy and a rather unusual one. It was an angel holding a baby in outstretched arms, swaying by elastic, a flying motion was produced. How I loved it and how glad I was to see Annes! But she did not seem the same. She looked tired and rather grown up and I missed her ever-ready laugh. After this Annes passed out of my life. I did not see her again but I believe that somewhere in some way she is an angel now.

After Annes left us another girl, Alice,was brought into the house. How glad she was to come and how hard she tried, but she was awkward,not trained as Annes was. I did not like to have her help me dress or comb my hair so I decided to get on without a personal maid. I have never had, nor wanted one since.

There did not seem much for Alice to do so she devoted herself to my baby brother. Devoted is the right word. I have never known greater love shown to a child not one’s own.

My Father paid wages

Of course my Father began to pay wages to those of our Negroes who remained with us. When pay day came for Alice she would go gaily off to town and invest all of her money in toys and sweets for my little brother. My Father had always provided her with clothes and she saw no reason why he should not continue to do so. Alice never left us until after my Father’s death and we were moving to another town, and she married.

There is another one of our Negroes outstanding in my memory, Marshal. He must have been about 40 years old when my Mother inherited him from her father’s estate. Marshal was far above the average Negro in intelligence and a skilled workman.

I had a table for teaparties

I had a little table for my doll teaparties that he made for my mother and her little sister- when they were children on their old plantation home near Columbus, Miss. This little table was so substantially made and so well put together that now, nearly ninety years old and serving for tea parties of four successive generations of little girls it is enameled in blue(?) a thing of beauty giving pleasure to my little granddaughter, a child of three.

I never remember seeing a surly look on Marshal’s face nor hearing an unkind word from him. How I loved to play about where he was, though I must have often been in his way, gathering little blocks for my playhouse or the long furling shavings that fell from his plane. (Plane may mean to you a wonderful machine flying in the air, but I refer to a tool with which carpenters dressed or smoothed rough lumber.

Marshall brought me a cage for my bird

After Marshall was free, I met him one day and, being happy over a new bird, asked him to make me a cage for it. In a short time he brought me a beautifully finished bird cage. How happy he seemed over my pleasure.

One night, I think about two years after the surrender, I was waked by my mother and told to get up and dress. My little brother was also taken up and dressed. When I asked why, my Mother, not letting the fright she must have felt show, replied, “We may go somewhere.” After awhile I went back to bed fully clothed, even to shoes. The next day I learned from some source that there was a threatened uprising of the Negroes against the whites and that Marshal was the leader. Our Marshal!

Marshal who was always so kind, who had made the little table for my mother in her childhood and the bird cage for me. I could not understand, nor do I to this day. I do not know how it was all settled but somehow Marshal did not seem the same. He did not come to see us so often, always kind and wanting to help, but not the same.

Mother moved to town

After my Father’s death, my Mother, wishing to be near her brothers, decided to move to another town. Marshal came to pack and crate the furniture for shipment, refusing the pay my Mother offered. He was at the depot to say good bye to his white folks. Years afterwards we read or heard he was killed resisting arrest. My Mother was grieved and said, “He was one of the most trusted Negroes my Father had.”

My Father never bought or sold a Negro. The ones we owned came to us from the estate of his father or my Mother’s father, and I believe to a certain extent the Negroes were given some choice as to which one of “Old Marster’s” children they went to. I never saw my father whip a Negro but once. Mose, a boy whose duty it was to care for his saddle horse had not fed the horse.

My Father asked, “Did you feed my horse?’

“Yes, sir. I sho did.”

“How did you feed it when I have the key to the crib?”

“I jumped up and got corn out of a crack.”

“Let me see how high you can jump Mose.” So taking his riding whip he gave Mose a few licks on his feet, making him jump. It seemed to be somewhat of a frolic to my Father and to Mose, but Mose was warned that the horse must be fed and no more lies told.

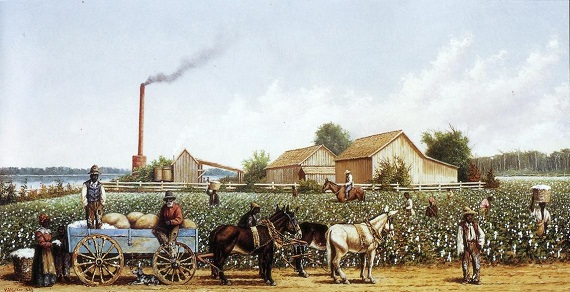

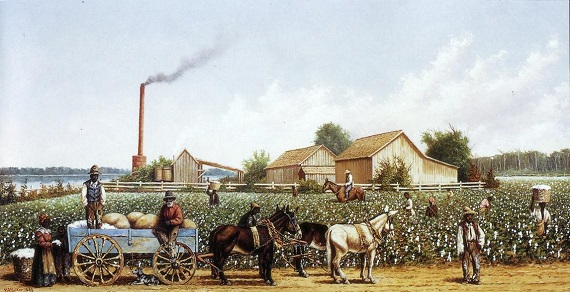

The slaves as I knew them were a happy, healthy people, laughing and singing. I especially remember the singing as they went about their work, out of doors. I believe they did not think it “manners” to sing in the house, but coming home from their day’s work in the fields, how strong and sweet their voices were raised in song.

My childhood passed quickly away. When fourteen years old I went off to boarding school and was no longer “little”. So as you ouly wished to know about when I was “little,” this is all.

(This was written when Mama was about 75 years old. She lived to be 97.)

Josie Bell Wilcox Thrash, B.S. Livingston University, sending an essay written by my mother, Clemmie Parker Wilcox. She was born Aug. 10, 1858, Butler, Alabama, m. William Dade Wilcox Jan. 16, 1884, died Sept. 23, 1955, Butler, Alabama. Her diploma was from Varona Female College, Varona, Miss., June 23, 1875.

Her father was Dr. Reden Nauflet Parker who had a drug store where Tillman Wright’s Drug Store is now and he was a partner of Dr. Edward Moody, when my mother was born. When Clemmie was 1 year old, the family moved to Enterprise, Miss. Thus, the recollections of Yankee troops. As a young woman she visited relatives in Butler, met and married Mr. Wilcox, and lived there the rest of her long life.