The 2020 presidential election took a decided turn as it moved into the final six weeks when Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a liberal icon, passed away, opening up a seat that would, if filled by a conservative, shift the ideological balance of the High Court, and bringing the issue to the forefront of what is already a raucous campaign.

Making matters worse, President Trump soon announced his intention to fill the seat on the Court before the election, nominating Amy Coney Barrett, a move that sent Democrats into a frenzy.

At least part of their anger was the fact that Trump decided to name a replacement during an election year, coming just weeks before voters cast their ballots. Democrats acted as though this had never been done, even though Obama nominated a replacement for Justice Scalia in 2016.

But, the truth is, many Presidents, including the very first chief executive, have nominated Supreme Court justices during election years. Washington did it twice in 1796, appointing Samuel Chase and Oliver Ellsworth, who would serve as Chief Justice. Both were confirmed the day after their nomination. Jefferson appointed a justice in the spring of 1804, William Johnson, who was confirmed two days later. Eisenhower made a recess appoint a month before the election of 1956.

Being out of power in the Senate, and with no filibuster allowed to stop the appointment, radical leftists, led by Senators Chuck Schumer and Kamala Harris, the Democrat vice presidential nominee, threatened retaliation, promising to “pack” the court if they win the White House and the Senate, with a proposal to add as many as three seats to a court that has contained nine seats since 1869.

Such threats are nothing new. The political left, whether under the name Federalists, Whigs, Lincoln Republicans, Yankees, Progressives, Liberals, Nationalists, Neo-Cons, or modern-day Democrats, have always fought hard to keep control of the Supreme Court to impose their agenda on the populace.

So, when it comes to conservative judges, especially for justices of the Supreme Court, liberals have used a variety of tactics to stop their nominations, including the use of vicious personal attacks and smear campaigns in the hopes of protecting the one branch of government not subject to popular sovereignty. By keeping the Court left-of-center, liberals can write laws from the bench and implement their unpopular policy goals with no opposition. But to do that they must maintain control of the court system, especially the High Court, at all costs.

In an interesting look through history, the left has used nearly identical rhetoric to attack conservative justices and strict constructionism.

In a public rally for James G. Blaine in Massachusetts on October 29, 1884, a young New York assemblyman named Theodore Roosevelt warned his fellow Republicans that the “next President runs a chance of having to appoint four judges of the Supreme Court,” and these judges would likely be “strict constructionists.” Such justices, he said, would change the country “from a mighty and prosperous nation into a confederation of petty and wrangling republics.”

The Republican Roosevelt favored “loose constructionists,” of the “school of Marshall and Story, the Federalists, and not…the school of Taney, the Democrat.” The type of justices favored by the Roosevelt’s party would decide “that the national banks are constitutional, that the law by which they are created and extended is constitutional, that the law providing for the suppression of pleuro-pneumonia and of kindred diseases by the National Government should be held constitutional,” he said.

Defeating Blaine that election year of 1884 was Grover Cleveland, a strict constructionist who made two appointments to the Court within a year of his first re-election campaign in 1888. In April, he appointed Melville Fuller, who Lawrence W. Reed of the Foundation for Economic Education has called “the best chief justice the Supreme Court has ever had.” But the previous December, in an effort to help end sectional tensions, Cleveland appointed Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar of Mississippi to an associate position on the Court.

Lamar was no ordinary judicial appointee. He had served in the US House during the 1850s, but then served as a delegate to Mississippi’s secession convention and authored the Ordinance of Secession, withdrawing the State from the Union. During the war, he served as a colonel in the Confederate army and in various government posts, including minister to Russia and special envoy to Britain and France. After the war, he was a professor at Ole Miss, a member of the US House, US Senate, and Secretary of the Interior under Cleveland.

A courageous man who was later featured in John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage, Northerners wasted little time attacking Lamar, not so much as a Southerner, which they hated, but as “unqualified” to sit on the High Court. One Massachusetts Senator opposed Lamar “not because I doubted his eminent integrity and ability, but because I thought that he had little professional experience and no judicial experience.” Such attacks are commonplace today, unless the nominee is a liberal, like Elena Kagan, an Obama appointee who had never served as a judge in any capacity.

In an oft-used class card tactic, the San Francisco Chronicle believed Lamar leaned “naturally and spontaneously to the side of the strong against the weak. He is a friend of monopolies.” One could substitute the name Lamar for Bork, Scalia, Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, or Kavanaugh with little difference. The attacks against conservative nominees to the Court have been nothing short of vicious, not to mention downright pathetic. Liberals have never been bothered by trashing a conservative’s reputation. And yet they say it’s the right that is “mean spirited.”

Packing the Court

But more than vicious, personal attacks, the left loves to manipulate the judiciary with “packing” schemes. Their first court-packing move came after the election in 1800. Routed by Jefferson’s Republicans, the Federalists were down but not out. They had one last trick up their sleeve. Since Jefferson, a Southerner, would sit in the White House, and his party would have majorities in both houses of Congress, Federalists decided they would control the agenda by judicial fiat.

The Anti-Federalists had warned against just such a possibility after reading over Article III of the new Constitution. “Brutus” wrote in January 1788 that a powerful judiciary would enable those in power to mold the government “into almost any shape they please.” And now Federalists would carry it out.

To keep their policies in place, the Federalists well knew that they could create courts, appoint judges to sit on the bench, and there was nothing the incoming Republicans could do about it, save impeachment, since the Constitution allowed federal judges to preside for life on good behavior.

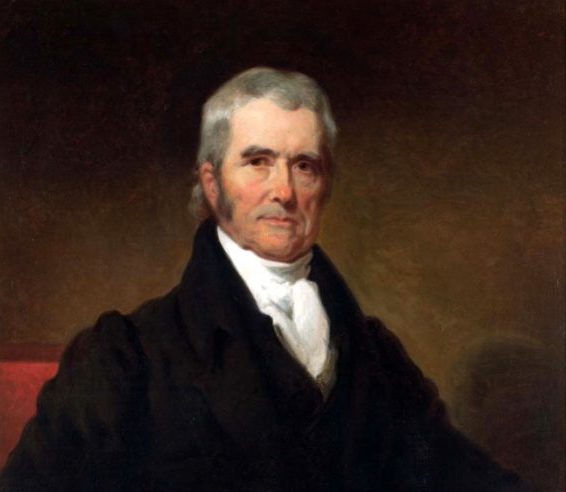

It’s one thing to appoint a replacement to a federal court during an election year; it’s quite another to appoint one after the election is decided against the party in power. But Adams did not let it stop him. On January 20, 1801, the outgoing President appointed John Marshall to the Chief Justiceship of the Supreme Court a little more than a month before Jefferson would assume the presidency. Marshall was confirmed on January 27 by the Federalist Senate. A fierce proponent of nationalism, Marshall used judicial power to solidify the Federalist agenda of centralizing power in Washington. He never found a supposed federal right he did not like.

In his last days in the White House, Adams also appointed a wealth of Federalist judges in the many new courts the out-going Federalist-controlled Congress hastily created with the Judiciary Act of 1801. They became known as Adams’ “midnight judges,” most of whom were named during the last night he resided in the Executive Mansion. Once in office, Jefferson and the new Republican majority in Congress fought hard to undue the Federalist-dominated judiciary with some success, but were unable to overturn it completely.

But that wasn’t the only Yankee move to pack the Supreme Court. Nearly seven decades later, nationalists were at it again. Vice President Andrew Johnson became President after Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865. Even though he had remained loyal to the Union, Johnson was still a Southerner and Radical Republicans in the North, though initially happy with Johnson, soon became suspicious and later downright hostile.

After adding a tenth seat to the Court in 1863, Congress decided to begin removing seats while Johnson was President. A vacancy occurred in April 1866 and Johnson named a replacement. But, a few months later, Congress passed the Judicial Circuits Act, which would begin the process. Johnson signed the bill because even he, like many in Congress, believed the Court, with ten justices, has become too large. But it’s likely that Radical Republicans also decided to remove seats because they did not want a Southerner to name any justices to the prestigious High Court.

By the time Johnson was out of office, the Supreme Court was down to seven seats. But when the justices issued a ruling that angered Congress, Republicans soon changed their tune, and all for political and policy reasons.

In 1862, to help finance the war against the South, as well as their other spending schemes, Republicans, with the urging of Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, passed the Legal Tender Act. This inflationary plan allowed for the creation and circulation of a national currency called Greenbacks, fiat money that did not have the backing of gold, though the Constitution specifically gives Congress the authority to “coin money,” not to print it.

In all, Congress issued more than $450 million in paper dollars during the four-year conflict, producing enough inflation to double the cost of living in the North. The United States had not seen that level of inflation since the days of the American Revolution with the old, worthless Continental dollar.

In 1870, the Supreme Court, in the case of Hepburn v. Griswold, ruled the Legal Tender Act unconstitutional in a four-to-three decision. The Chief Justice in that case, who sided with the majority, was none other than Salmon P. Chase. The decision did not sit well with Republicans in Congress, who raised the number of seats on the Court back to its present total of nine. President Ulysses S. Grant then nominated two new Stalwart Republican justices, and the Court reversed itself a year later, in Knox v. Lee, allowing Congress the authority to issue paper currency.

Another seven decades in the future saw the most famous court-packing scheme, which actually failed, but ultimately achieved the same objective. By 1937, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was in the first year of his second term as President, seeking to add to his signature New Deal program. But the Supreme Court had begun invalidating some of it, including the National Industrial Recovery Act and the Agricultural Adjustment Act.

FDR constantly railed against the High Court and it’s “horse and buggy” interpretation of the Constitution. So, after his landslide re-election over Alf Landon in 1936, he proposed the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, which would allow him to appoint a new justice to the Court for every one that was over the age of 70. Given the makeup of the Court at the time, Roosevelt could have raised the number of seats to 15. The idea was purely politics in order to shift the ideological makeup of what would essentially be a new Court in the hopes that it would uphold the New Deal and anything else FDR wanted to do.

However, he ran into stiff opposition to the plan and it failed. But one justice in particular, Owen Roberts, began to shift his votes in favor of New Deal legislation. It is known as “the switch in time that saved nine.” Before his tenure as President ended, FDR has appointed nine justices to the US Supreme Court.

First Among Equals?

But why is there such rancor over the Supreme Court? Such vicious political fights over any branch of the federal government should be evidence enough that it has too much power, far more than it was ever intended to possess.

Today the Supreme Court has become the most powerful branch of government. It writes laws, approves, and disproves, actions by the legislative and executive branches, and seems to oversee societal morality. The courts have imposed abortion rights, stripped prayer from schools, expanded eminent domain, limited property rights, interfered in state affairs, and generally caused mayhem, all in the name of liberalism. As Clyde Wilson has rightly contended, sovereignty no longer resides with the people of the States, but in the US Supreme Court. Today, judicial review is as strong as ever.

In 2002, Kenneth Starr authored a book about the Supreme Court that he entitled First Among Equals, in which he argued that the judiciary is “the branch of government with the authoritative role in vital issues that deeply affect American life and politics.”

Historically, though, such an opinion has no basis in fact. The Supreme Court was never designated as the strongest of the three branches. A more accurate description would be last among equals. The branches of the federal government were never meant to be co-equal.

Until the 1930s, the highest court in the land didn’t even have its own building, but met in the basement of the Capitol, or where ever Congress allowed them to meet. This was not a mistake but clearly intentional. Examine a copy of the original map of the City of Washington, drawn up by its planners, and you will see that a building to house the Supreme Court was not included.

It is also not an accident that provisions for the Supreme Court were placed in Article III of the Constitution, while Congress, clearly intended to be the stronger of the three branches, was outlined in Article I, and the Office of the President was established in Article II.

Furthermore, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 proposed a Council of Revision, a body that would be armed with a veto power over all national and state laws. The Council had the authority to review every law passed throughout the Union and to decide what would be allowed and what would not be. The convention ultimately rejected the idea – three times.

The Convention created both the Supreme Court, to exercise all judicial powers in cases brought before it, and a President who would take care of executive responsibilities, including the power to veto, or reject, bills passed by Congress. The Supreme Court was not entrusted with such power.

The Court does not legally possess nearly the power it has usurped today, and does not have an exclusive right to interpret laws and the Constitution. There is nothing in the entirety of Article III of the Constitution that gives federal courts that power.

Chief Justice John Marshall, in the case of Marbury v. Madison in 1803, assumed for the Supreme Court the power of judicial review, that is to make the final decision on the constitutionality of all laws. The decision angered President Jefferson, who believed the federal courts, then under Federalist judges, were establishing a judicial tyranny over the rest of the government.

“The Constitution…meant that its coordinate branches should be checks on each other,” Jefferson said. “But the opinion which gives to the judges the right to decide what laws are constitutional and what not, not only for themselves in their own sphere of action but for the Legislature and Executive also in their spheres, would make the Judiciary a despotic branch.”

Jefferson was skeptical of the right of the Supreme Court to exercise judicial review. “The question whether the judges are invested with exclusive authority to decide on the constitutionality of a law has been heretofore a subject of consideration with me in the exercise of official duties. Certainly there is not a word in the Constitution which has given that power to them more than to the Executive or Legislative branches.”

Other Presidents had similar opinions and took even harsher action when the Court interfered with the responsibilities of the executive. Jackson and Lincoln ignored Court decisions, while others used one of their strongest weapons, the veto pen, to make their own decision about the constitutionality of laws. Early American Presidents believed they had a duty to determine the constitutionality of federal laws before approving and then acting on them.

In 1817, James Madison vetoed a bill for federal funding of internal improvements, projects such as roads and canals, using constitutional arguments to make his case.

The legislative powers vested in Congress are specified and enumerated in the eighth section of the first article of the Constitution, and it does not appear that the power proposed to be exercised by the bill is among the enumerated powers, or that it falls by any just interpretation within the power to make laws necessary and proper for carrying into execution those or other powers vested by the Constitution in the Government of the United States.

James Monroe did likewise in 1822 with his Cumberland Road Bill Veto: “I am compelled to object to its passage and to return the bill to the House of Representatives, in which it originated, under a conviction that Congress does not possess the power under the Constitution to pass such a law.”

In 1832, Andrew Jackson vetoed the re-chartering of the Bank of the United States in a famous altercation with Congress: “Having considered it with that solemn regard to the principles of the Constitution which the day was calculated to inspire, and come to the conclusion that it ought not to become a law, I herewith return it to the Senate, in which it originated, with my objections.” The bank bill, Jackson wrote, is not “compatible with justice, with sound policy, or with the Constitution of our country.”

President Franklin Pierce rejected two bills of dubious constitutionality during his one term in the White House. The first was a bill for public works in 1854: “On such an examination of this bill as it has been in my power to make, I recognize in it certain provisions national in their character, and which, if they stood alone, it would be compatible with my convictions of public duty to assent to; but at the same time, it embraces others which are merely local, and not, in my judgment, warranted by any safe or true construction of the Constitution.”

The same year, Pierce vetoed a bill that would have provided government funds for the mentally insane. “I can not find any authority in the Constitution for…public charity,” he told Congress. “To do so would, in my judgment, be contrary to the letter and spirit of the Constitution and subversive of the whole theory upon which the Union of these States is founded.”

Grover Cleveland became the “Veto President” when he set a record of 414 vetoes in his first term alone. In 1887 he rejected a bill to provide seeds for drought-stricken farmers in Texas. “I can find no warrant for such an appropriation in the Constitution,” he told Congress.

Early Presidents did not believe in the modern notion that Congress should pass any law it chooses, and then allow the courts to sort it out. Such actions would have been considered a dereliction of duty.

In addition to the President, Congress also has explicit constitutional authority over the Supreme Court. The Constitution vests Congress with “all legislative power,” that is all lawmaking authority. This is precisely why courts are not allowed to make laws from the bench.

Although many Southerners may bristle at an example from Radical Republicans in Congress, they did take some constitutional actions in regards to the High Court.

Though the Constitution sets the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction, Congress has the authority to limit the Court’s appellate jurisdiction, a tactic that modern-day conservatives discuss from time to time, yet never implement. Though ridiculed by some as “unconstitutional,” Congress possesses the constitutional power to limit cases the Court can hear.

Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution reads, “In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.”

Congress has used that power in the past when needed, most notably during the heated days of Reconstruction in the case of Ex Parte McCardle.

In 1869, a Mississippi newspaper owner and former Confederate general, William McCardle, wrote and published a series of editorials criticizing the North and its Reconstruction program. Acting under the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, which provided for martial law, military commissions and tribunals, and the abolishment of the right of habeas corpus, the Union military commander in McCardle’s district arrested him. McCardle sued to gain his freedom under the Habeas Corpus Act of 1867, a law passed by Congress that defined, by federal law, the rights under habeas corpus.

The Supreme Court, under Chief Justice Chase, had previously limited federal authority to try civilians in military courts, with Ex parte Milligan, and Radicals in Congress feared that if the Court heard the McCardle case, it might throw out the Reconstruction Acts, which would threaten the entire Reconstruction program.

Congress, acting under Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution, removed the Court’s jurisdiction in all cases arising under the Habeas Corpus Act by attaching a rider to an appropriations bill. When the case came before it, the Court upheld Congress’s right to withdraw its jurisdiction.

With such abundant historical evidence, it is perplexing why conservatives today would place so much trust in the Supreme Court, an unelected body that has so much influence to affect public policy, when clearly the other two branches have been awarded more power by the Constitution.

The reason is politics. It’s easier for members of Congress to allow the unelected Court to handle hot-button political issues, leaving them free to dodge them. But in so doing they have established a dangerous precedent, surrendering their constitutional powers to an unelected oligarchy with lifetime appointments.

As Thomas Jefferson wrote to a friend, “To consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions [is] a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy. Our judges are as honest as other men and not more so. They have with others the same passions for party, for power, and the privilege of their corps.”

Justices, with their power, are “more dangerous” because “they are in office for life and not responsible, as the other functionaries are, to the elective control. The Constitution has erected no such single tribunal, knowing that to whatever hands confided, with the corruptions of time and party, its members would become despots.” Jefferson had it exactly right.

If Democrats win and do “pack” the Court, conservatives should reject calls to retaliate in kind. The answer is not in manipulating the Supreme Court; the answer is in reducing its power.