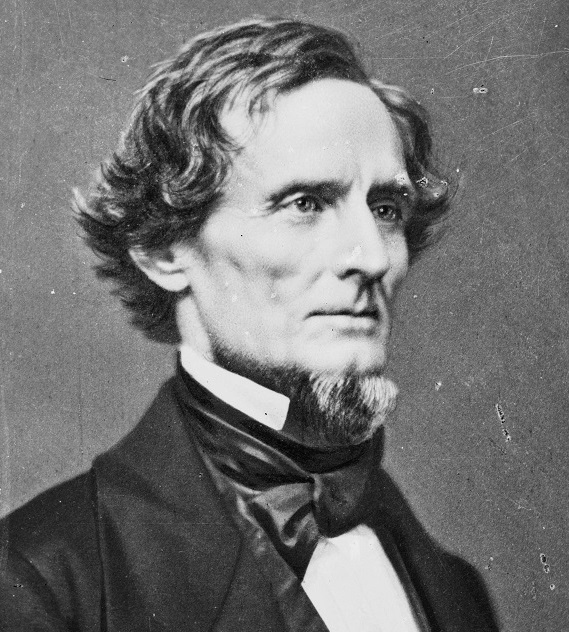

Of all people to go to when attempting to answer the question of why the Confederacy fell, there is probably no one more qualified than Jefferson Davis himself, the first and last president of the Confederate States of America. In an excerpt from his work, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, he writes,

“The act of February 17, 1864 […], which authorized the employment of slaves, produced less results than had been anticipated. It, however, brought forward the question of the employment of the negroes as soldiers in the army, which was warmly advocated by some and as ardently opposed by others. My own views upon it were expressed freely and frequently in intercourse with members of Congress, and emphatically in my message of November 7, 1864, when, urging upon Congress the consideration of the propriety of a radical modification of the theory of the law, I said:

Viewed merely as property, and therefore as the subject of impressment, the service or labor of the slave has been frequently claimed for short periods in the construction of defensive works. The slave, however, bears another relation to the state—that of a person. The law of last February contemplates only the relation of the slave to the master, and limits the impressment to a certain term of service

But, for the purposes enumerated in the act, instruction in the manner of camping, marching, and packing trains is needful, so that even in this limited employment length of service adds greatly to the value of the negro’s labor. Hazard is also encountered in all the positions to which negroes can be assigned for service with the army, and the duties required of them demand loyalty and zeal.

In this aspect the relation of person predominates so far as to render it doubtful whether the private right of property can consistently and beneficially be continued, and it would seem proper to acquire for the public service the entire property in the labor of the slave, and to pay therefor due compensation, rather than to impress his labor for short terms; and this the more especially as the effect of the present law would vest this entire property in all cases where the slave might be recaptured after compensation for his loss had been paid to the private owner. Whenever the entire property in the service of a slave is thus acquired by the Government, the question is presented by what tenure he should be held. Should he be retained in servitude, or should his emancipation be held out to him as a reward for faithful service, or should it be granted at once on the promise of such service; and if emancipated what action should be taken to secure for the freed man the permission of the State from which he was drawn to reside within its limits after the close of his public service? The permission would doubtless be more readily accorded as a reward for past faithful service, and a double motive for zealous discharge of duty would thus be offered to those employed by the Government—their freedom and the gratification of the local attachment which is so marked a characteristic of the negro and forms so powerful an incentive to his action. The policy of engaging to liberate the negro on his discharge after service faithfully rendered seems to me preferable to that of granting immediate manumission, or that of retaining him in servitude. If this policy should commend itself to the judgment of Congress, it is suggested that, in addition to the duties heretofore performed by the slave, he might be advantageously employed as a pioneer and engineer laborer, and, in that event, that the number should be augmented to forty thousand.

Beyond this limit and these employments it does not seem to me desirable under existing circumstances to go.[…] Subsequent events advanced my views from a prospective to a present need for the enrollment of negroes to take their place in the ranks. Strenuously I argued the question with members of Congress who called to confer with me. To a member of the Senate (the House in which we most needed a vote) I stated, as I had done to many others, the fact of having led negroes against a lawless body of armed white men, and the assurance which the experiment gave me that they might, under proper conditions, be relied on in battle, and finally used to him the expression which I believe I can repeat exactly: “If the Confederacy falls, there should be written on its tombstone, ‘Died of a theory.'”

The theory referred to was not a theory of slavery writ large, or else Davis would be condemning himself, since he remained a defender of slavery until his death, but it was a specific theory, that had gained traction in the South in the years prior to the outbreak of the war. The theory’s name was polygenesis.

Polygenesis was the idea that the races of humanity had distinct origins. In the context of the largely Christian South, with reference to blacks and whites, this usually meant the idea that white people were descended from Adam, and black people were descended from another “Adam”. There were all kinds of variations on the theory; having to do with Cain intermarrying with the races of the “Other Adams”, having to do with Ham intermarrying with the Other Adams, simply positing that blacks were a distinct and inferior species of humanity from whites, or in the most extreme cases, positing that blacks were not human at all and were instead beasts that were taken on the ark with Noah. A fantastically informative article which I encourage everyone to read in full by Christopher Luse titled Slavery’s champions stood at odds: polygenesis and the defense of slavery goes into detail about the Christians who defended slavery against both the abolitionists as well as the polygenists:

“Defenders of Christian slavery noted the ominous fact that abolitionism and polygenism arose together. Until the 1830s, antislavery remained weak, apologetic, and reformist instead of revolutionary. Until the mid-nineteenth century, ethnologists overwhelmingly defended Genesis and embraced monogenesis. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, researchers such as German Johann Blumenbach, Frenchmen Comte de Buffon and Cuvier, and British James Prichard all staunchly defended the common origin of humanity. Only in the sectional crisis of the 1850s did the “unity controversy” became [sic] truly heated.

Proslavery Christians frequently equated both abolitionists and ethnologists with a radical desire to overturn society. George Howe, professor of theology at the Columbia (South Carolina) Theological Seminary, noted the “coincidence between the infidel opposers of slavery and its infidel defenders.” Both ethnologists and abolitionists displayed the same overweening confidence in rationalism and the same rejection of revelation and traditional authority. Both rejected the scriptures when they stood in the way of their radical theories. Southern Christians believed that it would be mad to throw away the Bible, the shield of slavery, to embrace a doubtful theory that would alienate religious sentiment around the world. A reviewer in the Southern Quarterly Review contended that the Bible remained “an immovable basis of truth” and embracing the new ethnology would allow enemies the moral advantage of representing “we hold our slaves only as a higher race of Ourangs” outside the precepts of Christian morality. The reviewer sadly concluded that the infidel science was “not only a new thing under the sun, but a strange and portentous anomaly in the progress of human experience.”

[…] Southern Christians viewed the ethnologists’ reinterpretation of the origin and nature of humanity as a fundamental threat. They vigorously contended that the unity of the races was interwoven throughout the Bible. The editor of the Presbyterian Richmond Watchman and Observer maintained, “The unity of the human race is the cornerstone of the edifice, and if that were removed, the whole fabrick of revelation would be worthless.” Opponents of the new ethnology repeatedly quoted Acts 17:26, where Saint Paul proclaimed in Athens that “God hath made of one blood all the nations which dwell upon the earth.” Southern denominational newspapers quoted Saint Paul again and again to defend the unity of the races. Richmond’s The Religious Herald complained, “If we accept that God ‘hath made of one blood all nations of men,’ we are told that this is a question of science and we must abandon it to the philosopher.” Christians also often cited Genesis 3:20, proclaiming Eve as “the mother of all living.” Southern Christians explicitly linked a defense of the unity of all humanity to the veracity of the Bible.

They believed that by relentlessly undermining the Bible, the ethnologists were also weakening the strongest defense of slavery.”

Many Christians in the South certainly were staunch defenders of orthodoxy, however, there was a much larger-than-acceptable faction that did not stand up for what was right in the way that they should have, alongside a small but vocal minority of those who did not care much for Christianity that paved the way for all kinds of evil, as described by the same article:

“A few scholars depart from the prevailing consensus and maintain that polygenesis played a major role in Southern thought. George Frederickson, in his seminal The Black Image in the White Mind, notes that the controversial Josiah Nott “was hardly a martyr to scientific truth,” suffering no personal harassment, but instead enjoyed widespread support. Nott’s biographer, Reginald Horsman, claims that “in spite of his anti-clericalism, he was deeply admired by the society in which he lived.” Nott wrote to his friend and fellow ethnologist Ephraim George Squier that despite his “infidelity” he enjoyed a thriving medical practice, claiming that he was the favorite of the local clergy. Nott freely admitted his ambition to “kick up a dam’d fuss generally” and gain renown. He maintained that “the great mass of the people of the South at least have sustained me & if I have done no other good, I have been at least been [sic] a successful agitator.”

The popularity of an “infidel” theory in a strongly orthodox South raises some interesting questions. Clement Eaton contended that by the late antebellum era, the vigorous freedom of debate evident in Jefferson’s generation had been crushed by a proslavery consensus. Yet, within a broad acceptance of slavery, Southern ethnologists could attack sacred religious dogmas, viciously slander leading clergymen, challenge accepted truths in science, and undermine established doctrines in moral philosophy. Within the “cotton curtain” an acrimonious debate raged over the nature of slavery, race, religion, and science. Southern ethnologists and clergymen argued over how to defend slavery. The controversy illustrated that it was safer in the Old South to be religiously heterodox than to be seen as weak on slavery.”

Jefferson Davis himself had apparently entertained polygenesis as evidenced in his statement in response to Senator Harlan in a fiery (and honestly, outright bonkers, for more reasons than one) senate debate on a bill that had to do with appropriating funds from the federal government for the education of black children in the District of Columbia on April 12th, 1860:

“Mr. Harlan: Do you then believe in the political and social equality of all individuals of the white race?

Mr. Davis: I will answer you, yes; the exact political equality of all white men who are citizens of the United States. That equality may be lost by the commission of crime; but white men, the descendants of the Adamic race, under our institutions, are born equal; and that is the effect of the Declaration of Independence.” (Emphasis mine)

White people being the “descendants of the Adamic race,” the implication was that black people were then not descendants of Adam. Earlier in the discourse between Senator Harlan and Senator Davis, Davis makes this statement further clarifying his association with ideas of polygenesis:

“When Cain, for the commission of the first great crime, was driven from the face of Adam, no longer the fit associate of those who were created to exercise dominion over the earth, he found in the land of Nod those to whom his crime had degraded him to an equality; and when the low and vulgar son of Noah, who laughed at his father’s exposure, sunk by debasing himself and his lineage by a connection with an inferior race of men, he doomed his descendants to perpetual slavery. Noah spoke the decree, or prophecy, as gentlemen may choose to consider it, one or the other.”

It should be noted, however, that Davis was apparently not a firm believer in these ideas, or at least he did not connect these ideas deeply with his day to day life, as he conveyed in this statement shortly after his remarks about the political equality of white male citizens: “This is not a debating society. We are not here to deal in general theories, and mere speculative philosophy, but to treat subjects as political questions.”

Fortunately, when the theories of polygenesis came head to head with the practicalities of winning the war and defending his people, Davis chose his people. Unfortunately, however, there were other Confederates who dragged their feet, as Davis describes:

“General Lee was brought before a committee to state his opinion as to the probable efficiency of negroes as soldiers, and disappointed the probable expectation by his unqualified advocacy of the proposed measure.

After much discussion in Congress, a bill authorizing the President to ask for and accept from their owners such a number of able-bodied negro men as he might deem expedient subsequently passed the House, but was lost in the Senate by one vote. The Senators of Virginia opposed the measure so strongly that only legislative instruction could secure their support of it. Their Legislature did so instruct them, and they voted for it. Finally, the bill passed, with an amendment providing that not more than twenty-five per cent. of the male slaves between the ages of eighteen and forty-five should be called out. But the passage of the act had been so long delayed that the opportunity was lost. There did not remain time enough to obtain any result from its provisions.”

So if someone asks why the Confederacy fell, instead of answering “slavery,” you can answer “polygenesis.”

Hello! In one quote here, there is mention that the Virginian Congressman opposed the bill allowing slaves to join the military. With that said, do you know, or know where I can find, how the other states voted on this? For example, how did Alabama’s or Mississippi’s Congressmen vote, and is there any pattern to the voting (i.e., Upper South voting like Virginia, Deep South together, etc.)?

The Library of Congress’ CSA Records Collection website page says that there are “acts and resolutions of the Confederate congress” within their collection, so if those voting records would be anywhere, that might be your best bet.

Link: https://www.loc.gov/collections/confederate-states-of-america-records/about-this-collection/

In a book called, “The Origin Of The Races,” the late Bob Barlow, a Bible believer, expressed his thinking that the races were formed after the judgement at Babel. So, not only were the lands and languages divided there, but skin color as well. If I recall correctly, I read the book, Barlowe said that the division of skin colors was a benefit, in spite of the fact that there was definitely a negative judgement at Babel. It helped one find his own tongue seeing a similar skin color. As far as the so-called “curse of Ham,” it wasn’t Ham who was cursed, but rather Canaan, Ham’s descendent. The execution of that curse was to be when Israel moved into their promised. They were suppose to utterly remove Canaan out of the land.

The execution of the curse had to with slavery, not genocide, but you’re right about it being Canaan who was cursed, not Ham. Ham just didn’t receive a blessing while the other two sons did. I wonder why Barlowe believed skin color came at Babel, and not just as a result of the different paths taken and geographical regions of the different peoples.

I respectfully disagree, sir, about why Israel was told to remove Canaan from the promised land. My understanding is it was because Canaan’s “father” saw Noah’s nakedness. Noah couldn’t curse Ham because God blessed all three of Noah’s son’s. Gen. 9:1. But, the most important reason, I think, is the Abrahamic covenant. Abraham was a descendant of Shem. So, Ham and Japeth were out. Even if Japeth’s seed was in that land, they were to be removed. As far as why Barlowe thought that skin color came at Babel, well, I did read his book, but it’s been years. I think it might be because it seems men, or most of the human race did not spread out as they were commissioned to do after the flood. So, we have internationalism in Gen. 12, then the judgement. And then, God letting the nations go their own way. So then, God makes his own, beginning with Abraham a Shemite.

I said Gen. 12, as far as the internationalism, but it is Gen. 11, not 12.

I could probably write a whole article on the issue of Canaan and Shem and their places in the promised land, but there’s no need for me to get into that here. I appreciate that you read the article and commented.

You’re welcome. Appreciate you writing. The author’s name is spelled without an “e” on the end. So, it’s Barlow.

Mr. Davis, it might interest you to know that my understanding of the Bible has to give a lot of thanks to C.I. Scofield, Confederate veteran. Ironically, though, I don’t have a Scofield reference Bible, but I know he was a big part in helping to recover dispensational truth in the 19th century. I also realize, but only to a small extent, that many Southerner’s were and are not happy with Scofield. I think it is felt he betrayed the betrayed the Southern cause after the war, or that he had a change of mind about its worthiness. Nevertheless Scofield made a great contribution to the recovery of Paul-ine authority.

I for one don’t see the quotes from JD as specifically, Pollygenisis. I see more of a position taken like that of Govener Wallace, that there might be a balck heaven and a white heaven, so the story goes. We can see there are good people and bad amung all races however, the person that denies a difference between the two are dishonest with themselves. Not only in culture but the flesh is different also. The reason the Confederacey has not triumphed yet is simple. The world belongs to Satan, and we do not side with Satan!

A question I would have is that if it wasn’t polygenesis, then what justification in the form of a theory (greed would not count here, because Davis specified it was a “theory” of slavery, not a vice) would they have for balking at the idea of freeing slaves in response to their service in the Confederate army?

As for the world belonging to Satan, I believe that is partly true at the moment. But, Revelation 12 describes how Jesus’ resurrection began a war in heaven. The angels won, so Satan was cast down to earth, and then v. 12 says Satan began war against the Church. I believe it’s our responsibility and destiny to win that war against Satan. His authority on earth is illegitimate; he’s a tyrant, and rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.

It’s my understanding that Southerners were much more optimistic in their eschatology prior to the war, but then after the war, a certain nihilism crept into their attitudes and they became much more pessimistic in their thinking. I think that is unfortunate because I believe we have victory in Christ.

The same verse, vs. 12, says that after Satan has been cast out, he knows he has but a short time. Two thousand years is a long time for a short time. Rev. 12, all of Revelation is still future. And the “man of sin” has yet to be “revealed,” 2 Thess. 2:3. That church being persecuted in Rev. 12 is not the Christian church. It’s Israel, it’s Jacob. That whole seven year time is called “the time of Jacob’s trouble,” Jeremiah 30:7. The Christian church in that future time will have already been caught up into the heaven’s. Satan is now, “the god of this world,” but his ungodly influence is through his “ministers of righteousness” and through principalities and spiritual wickedness in “high places.” That’s in the heaven’s. He will shift his focus directly on the earth and particularly against Israel when this age of grace has concluded.

I don’t want to fill the comments here with theological discussion somewhat unrelated to the content of the article, but I may, I won’t guarantee it, but I may write a separate article about Southern theology, and eschatology in particular. I appreciate your mention of Scofield and your willingness to discuss these things though. An article on theology, even Southern theology, may not be a fit for the Abbeville Institute blog here, so if I write that article and it’s not a good fit for this website, I’ll most likely publish it on my personal substack, which is CodyDavis.Substack.com. You can subscribe there if you are interested.

I do understand your point and have been aware of it. I really have not meant to be a disruption of Abbeville’s purpose here. I respect it. I had taken a great in Southerm history and that war, in trying to understand that whole time, even going back to the Revolution. I’m not different from many here, but I’ve traveled to learn about all this; I’ve done a good amount of reading on it: Emory Thomas, Shelby Foote, Edwin Coddington, James I. Robertson, the Kennedy twins, DiLorenzo. Of course, Clyde Wilson, Boyd Cathy, C. Chalk, V. Protopapas. The other terrific writer’s here. I’ve talked with Sam Dickson. Again, not much different from many here. But of course, I’m also a Bible believer. So, when Bible opinion’s are expressed here, and I’ve noticed they are, it can be difficult to know whether to input or not. Because you’re more a contributer, I suppose the balance should be more your way. I’m not sure. But, I definitely don’t mean to interfere or make waves with Abbeville. I appreciate what they’re trying to do.

I certainly haven’t taken any offense, and I would think that no one else at the Institute has taken offense either. I sincerely appreciate the engagement with the article. Many people at the institute are probably more aligned with the theological views you have expressed rather than my own, if I had to guess.

thats interesting stuff. if my genealogy is correct i am 1 percent black, from freed slave, slave-owning, blacks on my dads side and freed slave blacks on my moms side circa 1740 to 1780 in eastern NC. some biblical passages mention there isnt jew or greek, but all are one in christ…i don’t know if the other persons that are not jew or greek were left out intentionally, but i think the book wouldnt have said ‘all are one in christ’ because there were other peeps than jews or greeks at the time. i guess where i take issue with some of these articles is ‘what were the bulk of yankees saying about race in parallel to the south?’ their broadsides were objectionable enough.

Yankee’s certainly didn’t have particularly magnanimous attitudes towards black people, but the power at the time was in Lincoln’s hands, and in changing the war from being about the union, to adding his version of equality as a war aim, he reframed the whole issue in a way that Southerners were not prepared for. Jefferson Davis was very quick to respond as needed, and this can be seen when he gave the speech that I quote in the article, where he suggests a “radical modification of the theory of the law”, but Southerners were not quite ready for that, as is demonstrated in the article.

The fact that the South “lost” is proof of the justice of our cause anyway, because “the Lord disciplines the one he loves”, and as for the cause of the North; “If you are not disciplined—and everyone undergoes discipline—then you are not legitimate, not true sons and daughters at all.”

It’s true all in Christ are one and there is no difference. In the passage you referred to, a Greek was a Gentile. The same passage also says circumcised and uncircumcised. And that was the major difference back then as far as God was concerned. Everyone aside from Israel, including the Greek, were the uncircumcised. Meaning on the outside. Circumcision was the “middle wall of partition.” That wall is down now, since Paul.

The anti-polygenist argument is straightforward and irrefutable. Even if one appeals to the “curse of Ham” argument, one cannot be descended from Ham (and hence from Noah) without being descended from Adam and Eve, the father and mother of all mankind. James Henley Thornwell, Dr. John Bachman, and Dr. Thomas Smyth come immediately to mind as stout defenders of monogenesis. For Thornwell’s rejection of polygenesis, see The Rights and Duties of Masters (1850), 10-11: https://archive.org/details/rightsdutiesofma00thor/page/10/mode/2up For Bachman’s work, The Doctrine of the Unity of the Human Race Examined on the Principles of Science, see: https://archive.org/details/doctrineunityhu01bachgoog/page/n6/mode/2up For the 1851 edition of Smyth’s book, The Unity of the Human Races Proved to be the Doctrine of Scripture, Reason, and Science: With a Review of the Present Position and Theory of Professor [Louis] Agassiz, see: https://archive.org/details/unityofhumanrace00smyt/page/n33/mode/2up

For so intelligent a man as Jeff Davis to fall for the “multiple Adams” nonsense is truly appalling. Davis appealed to the “descendants of Ham” argument in a speech to the U.S. Senate on 2 March 1859, but he makes no mention of polygenesis. In the same speech, Davis does refer to slaves as “the lower race of human beings,” but I never thought he was using the word “race” in the polygenist (or dare I say Darwinian) sense of the word.

Yes, it is unfortunate that Jefferson Davis apparently entertained theories of polygenesis in hypotheticals, but I respect him for his actions. He treated his slaves well, and black people well generally, and as the article mentions, he abandoned whatever intellectual adherence he had to polygenesis in favor of the “radical modification of the theory of the law” he talked about, so that the Southern people could win their independence. That speech was like the Confederate Gettysburg Address in my opinion.

to me this is the federal republic issue…the population of the northern states felt what about the ‘African race’…’hey homey, glad to have you as a neighbor.’? i seriously doubt it. while the South was i think, shown to be much more racially mixed than the north. so the Ham and Israel stuff was to be of what consequence when demanding a preserving of a gentile union or not?

I think the case for ascribing polygenesis to Davis here is weak to non-existent. The fact that he refers to whites as descendants of Adam in a Senate speech does not imply that he things blacks have a different lineage. If it can be shown from some other material that Davis explicitly embraced polygenesis, then his Senate speech could be seen as alluding to that, but otherwise it proves nothing and this assertion becomes a theory in search of evidence.

The extended quote about Cain and Ham cited from earlier in the same exchange with Harlan has absolutely no relationship to polygenesis; it is a straightforward summation of the biblical record in Genesis. Indeed, the whole theory of polygenesis requires one to jettison the book of Genesis altogether and fabricate a dual seed line origin for these non-adamic bipeds, completely ignore the biblical account of the Flood which states that ALL Postdeluvian mankind descended from Noah, ignore Gen 10:6 – 7 which reveals black s are descended from Ham through Cush, Acts 17:26 which affirm ALL mankind is of one blood, Romans 5 which states we are all descended from Adam and innumerable other scriptures. Polygenesis is simply incompatible with Christian teaching and no thinking Christian would touch it and I believe that extends to Jefferson Davis.

As far as the question of why people in the Confederate govt would be opposed to using slaves for military service there is a very straightforward answer, because throughout history, military service in defense of the republic has often been equated with citizenship in the republic. To allow a man to bear arms is to imply he has a claim on being admitted to the polis. That would be a very radical and perplexing issue to deal with in a Confederacy that was nearly 40% in its black population.

The words of Davis about white people being “descendants of the Adamic race” are found in a context in which he and Senator Harlan were comparing and contrasting white people and black people, so the clear implication in context would be that black people were not descended from Adam.

You can read the full context for yourself and verify whether I am accurately representing Davis’ words here: https://books.google.com/books?id=gyfnAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA1682&dq=%E2%80%9CThis+Government+was+not+founded+by+negroes+nor+for+negroes,%E2%80%9D+davis&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjaxumfqPvLAhWmlYMKHfULCIMQ6AEIIjAB#v=snippet&q=Davis%20adamic&f=false

In all my reading of Genesis, I have never seen mentioned an “inferior race of men” that Cain found in the land of Nod, and neither have I seen anything mentioned about Ham having a connection with an inferior race of men. Further, the curse that had to with slavery was aimed at Canaan, Ham’s son, and not Ham himself, as is suggested by Davis. Those ideas about Cain and Ham’s connections with inferior races of men, while not found in Genesis, can be found in the writings of Samuel A. Cartwright, a popular polygenist in Davis’ time who attempted to use the Bible as a defense of polygenesis.

They can be seen expressed by Mr. Cartwright at this link, on page 134, in Debow’s Review, published 1860: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/moajrnl/acg1336.1-29.002/133?page=root;size=100;view=image

It is very unfortunate that Davis entertained these ideas, but we all have our blind spots. Different times are prone to different errors, and I mentioned in another comment here that despite Davis’ apparent intellectual adoption of these ideas, he lived in a way that was indicative of high moral character, and in the article I noted how he abandoned polygenist ideas so the war could be won and the Southern people could have independence. God tested him and he passed.

The issue of allowing slaves to fight in the war certainly was a radical issue, which is why Davis suggested a “radical modification of the theory of the law”. He had already more or less sorted the issue through his speech that was given and it was up to the Southern people to take it or leave it. The law only would have allowed blacks who had fought successfully in the war to be freed, which meant that the amount of free blacks would be much less than the full black population, especially after subtracting all female slaves from the equation, as well as children and the elderly; and certainly after the amendment that specified no more than 25% of the male slaves aged 18 to 45 could be enlisted. Freedom from slavery as payment for service in the military did not necessarily equate to participation in civic life to it’s full extent. They could have remained as foreign residents, rather than native citizens. Even white people that did not own land were not allowed to vote in the early decades of the Republic, so there would be no inconsistency in continuing to disallow black people from voting, even if they were freed after fighting in the war. Their service would have been similar to the service of mercenaries and their payment would have been manumission; there was no necessity to involve total integration into the American body politic as part of the transaction. The precise reason, and in my view the only viable reason left after all these considerations, as to why it would be a “radical and perplexing” issue is because of the “theory” of polygenesis.

if i recall in grants words southerners and native Americans were in ways inferior. civilisation was to brought upon them?

I do think the black race came from Ham, but I don’t think Gen. 10:5-6 shows this at all, nor does Genesis 9:22-27. A verse which better reflects that the black race came from Ham is Psalm 105:23. The divisions of families, tongues and nations, mentioned in Gen. 10 do not begin to occur until after the judgement in Genesis 11 at Babel. Also, I think a strong case can be made that the races were made in Genesis 11, not in Genesis 9.

Why did the Confederacy fall? Because it 1) struck at exactly the wrong time, and had 2) bad leadership that 3) insisted on fighting an honorable war instead of fighting to win.

1) Lincoln was an autistic madman with no regard for human life and an enormous messiah complex. Either declare independence under the ineffectual Buchanan, or wait Lincoln out and declare after he’s gone.

2, 3) Robert E. Lee was the finest and most honorable gentleman that this country has ever produced. But what the south needed was a low-down, dirty, ball-stomping, eye-gouging, back-shooting, dishonorable snake in the grass. Do you want to win, or not? If you do, then do what you need to win. If not, then don’t fight at all.

We can’t make the same mistakes again.