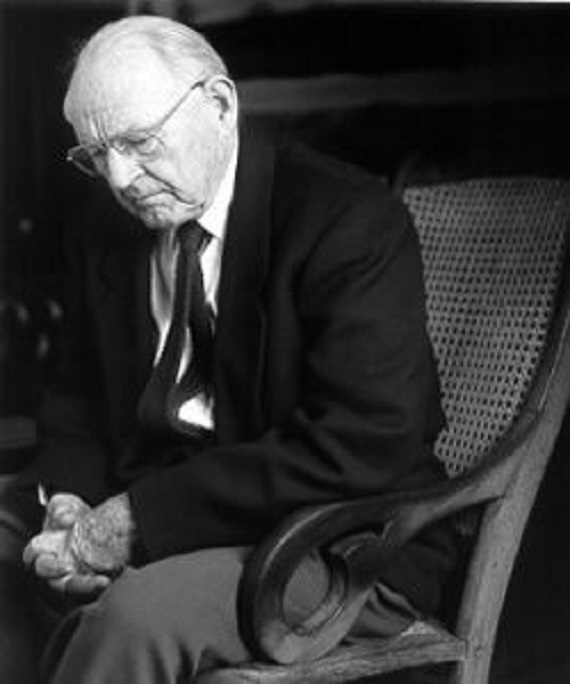

Andrew Nelson Lytle—novelist, dramatist, essayist, and professor of literature—extolled the order of the family, which by the 1930s he thought all but spent, precisely because it was rooted in the very concept of divine order that the modern world had decried and rejected. As patriarchy deteriorated, as acceptance of divine supremacy vanished, the family languished, and with it the community and the nation. Once more, the world tumbled into chaos.

I.

For Andrew Lytle, the pioneer, the semi-nomadic backwoods frontiersman, was the quintessential American. The tramp, the hobo, the outcast from the capitalist system was his twentieth-century spiritual descendant. Time and circumstance set the one apart from the other. The end of pioneering was settlement, “the successive stages of one movement,” as Lytle characterized it, which implied the establishment of families and communities.[1] The drifter, by contrast, was in perpetual motion, traversing the countryside without purpose or direction, because in Depression America there was “no longer any place to go.” Discarded and displaced, these vagabonds and fugitives had renounced “the slavery of technology… [and], driven by a vague nostalgia to wander upon the face of a continent,…” had become “the mass of this century’s backwoodsmen.”[2]

Lacking a proper medium, the qualities essential to the endurance and success of the American pioneer strength, independence, tenacity, and resilience had grown decadent and pernicious, giving “to the big businessman his ruthless drive, to the gangster a cruel realism, and to the walkers of asphalt a vicarious feeling of power which readily makes them tools of those who possess power.”[3] In important respects, these men were as much the victims of capitalism as were the hobos and the tramps whom the system had disinherited. Their ambition and self-reliance had been virtues on the frontier. With the coming of the industrial revolution, these old virtues became new vices because of the terrible power that machines placed at their disposal. Their moral degeneration began when they perceived the opportunity to make money quickly and in abundance. With modern life thus quickened by the inexhaustible striving and the remorseless ambition of the twentieth-century pioneer, it was no surprise to Lytle that American society had begun to fragment and Western Civilization to succumb to the throbbing of dictatorship.

Tyrannical regimes disclaimed transcendent authority and embraced instead an abstract power that originated within history itself—a power that rendered man the final judge of man. The resulting political arrangements condemned human beings either to blind obedience or to partisan conflict. A product of the human will unrestrained by divine ordinance, this dispensation concealed the truth that all power emanated from, and returned to, God. Anything less than the full acknowledgment of divine sovereignty was “selfish and therefore partial, and hence incomplete. It is this incompleteness,” Lytle ascertained, “which is Satan’s domain.”[4] The only responsible alternative to despotism lay in the revival of a Christian polity founded on the communion of families. No monolithic, totalitarian state could hope to subjugate a collection of independent families living on the land. The family was “the source of the traditional and Conservative state,” Lytle told James B. Graves, associate editor of Review of the News, in 1983.[5] For that reason the Fascists and the Communists alike opposed the family and sought to dismantle it. No corporate body, whether family, church, or aristocracy, could be permitted to intervene between the government and the individual, who at all times had to be made to feel his weakness, vulnerability, and dependence. The modern totalitarian state, Lytle recognized, sought to control every aspect of life, public and private. Nothing in theory was beyond its purview, and every means, including mass execution and mass starvation, was germane to realizing its ends.

Lytle extolled the order of the family, which by the 1930s he thought all but spent, precisely because it was rooted in the very concept of divine order that the modern world had decried and rejected. The familial hierarchy imitated the structure of creation, with the patriarch, God’s surrogate on earth, responsible for the welfare of his property, wife, children, and household dependents. There was little in the order of the family that could be mistaken for democracy or equality. The “Christian domestic ruler of people, flocks and herds, and growing things,” the patriarch “was committed to the care and keeping of those under him. He understands this,” Lytle stated, “and delivers up at death this care and keep to God’s Son.”[6] Family and household were thus, in Lytle’s judgment, concerns more spiritual than material. Just as money, an abstraction par excellence, could not replace land as the source of wealth, so neither could the businessman, financier, manufacturer, or politician substitute for the patriarch of old. Order in the family, as in the state, rested on legitimate, as opposed to imperious, authority and discipline. Once those foundations had eroded, individual members of the family, like individual citizens of the state, tended to follow their private interests at the expense of the common good. As patriarchy deteriorated, as acceptance of divine supremacy vanished, the family languished, and with it the community and the nation. Once more, the world tumbled into chaos.

The representation of the patriarchal family situated Lytle’s thought in the context of southern intellectual history. His was a Christian patriarchy. Before the Civil War, southern thinkers, both secular and religious, denounced the violence intrinsic in the unalloyed patriarchy of the ancient world, such as the power of life and death, which the Roman paterfamilias exercised over his wife, children, and slaves. As an alternative, they hailed the mitigating influence of Christianity that admonished men to respect the humanity of those, including the slaves, whom God had entrusted to their care. “The Slave Institution at the South,” proclaimed Christopher G. Memminger, the future Confederate Secretary of the Treasury, “increases the tendency to dignify the family”:

Each planter in fact is a Patriarch—his position compels him to be a ruler in his household. From early youth, his children and servants look up to him as the head, and obedience and subordination become important elements of education. Where so many depend upon one will, society assumes the Hebrew form. Domestic relations become those which are most prized–each family recognizes its duty–and its members feel a responsibility for its discharge. The fifth commandment [Thou shall not kill] becomes the foundation of Society. The state is looked to only as the ultimate head in external relations while all internal duties, such as support, education, and the relative duties of individuals, are left to domestic regulation.[7]

Like his antebellum counterparts, Lytle applauded the virtues of such inequality, which, in any event, he saw as inescapable since it was imbedded in human nature. “A family is never a democracy,” Lytle insisted, and equality prevailed “only in the sight of God, at our last awakening,… measured by the last four things, death, Judgment, Heaven, or Hell.”[8] In the South, Lytle maintained, such unequal relations had yielded not a vicious competition among individuals that resulted in a war of all against all in which survival of the fittest was the only law, but rather in a stable, cooperative venture in which husbands, wives, children, kin, and slaves each attended the family and the household and were, in turn, sustained by them “according to their various needs and capacities…. Each member,” Lytle continued, “is called upon to deny as much of his individual nature in the service of the whole, and this service sustains the common love and life.” [9] Forestalling the penetration of market values and shielding male heads of the household from undue interference by the state, the Christian families of the Old South had perpetuated independence and responsibility and thereby had engendered “a richer sense of mystery and… the larger meaning of life,” which the present had extinguished.[10]

For those reasons alone Lytle deplored the undoing of the traditional family “as a social unit [that had] so clearly defined the South.”[11] The traditional family with its many and various blood ties, which joined the living to the dead and the unborn, was the embodiment of Christian love, symbolized most fully in children. The modern family, on the contrary, was an empty vessel, not waiting to be filled but already drained of significance, from which intimacy, affection, and love had fled and around which the fetid odor of selfishness, greed, and enmity still lingered. “The hearthstone is no more,” Lytle admitted. “The family is a husk, committed to keeping up the appearance of what a family is.”[12] Although there is no evidence that Lytle read, or had even a passing familiarity with, the work of the English historian Christopher Dawson, his vision of the patriarchal Christian family closely resembles Dawson’s own.

Lytle agreed with Dawson, for instance, that the patriarchal family was not an instrument designed to abet the subjugation of women. Family life entailed discipline, restraint, and sacrifice from all members; “even the father himself,” Dawson noted, “has to assume a heavy burden of responsibility and submit his personal feelings to the interests of the family tradition.”[13] Moreover, the spiritual dimensions of the family, attendant in part upon the rise of Christianity, had transformed the meaning of womanhood, conceiving the ideal figures of virgin and mother, a testament to the homage that women garnered in a healthy society. A commanding matriarchal presence also suffused Lytle’s image of the family. The domestic order depended on women. They not only gave birth to the next generation, but were also the bearers of culture and tradition. They seduced men into virtue and civilization, and were the origin and conduit of manners and memory. They governed the family as the power behind the throne, and safeguarded the purity of the blood. “Superficially,” Lytle expanded, “woman was put into the role of a creature above the brute nature of man, which delimited both man and woman; romantically she was raised to the `divine’ and set upon a pedestal, which actually derives from our pagan inheritance.”[14] With women at its heart, the family was the indispensable element in any community worthy of the name. Good order in the family and the household implied good order in the state and the nation.

Family discipline also subdued human nature and maintained proper relations between the sexes. Regulating sexual activity was among the two cardinal purposes of the family; the other was to ensure the bearing and the rearing of children in a way that preserved social coherence and human identity. “The whole tendency of modern anthropology,” Dawson explained, “has been to discredit the old views regarding primitive promiscuity and sexual communism, and to emphasize the importance and universality of marriage.”[15] Or, as Lytle argued, the stability of society rested on marriage as an institution and a sacrament. The restraints of marriage, sexual and other, opposed the dangerous volatility of feeling, which prompted men to emphasize desire at the expense of duty. Adultery, like war, endangered social peace. “The family,” Lytle declared, “is the one thing that lasts and by which you can be defined in the fullness of your being.”[16] To accomplish that task required men to temper their natural instincts and to serve a larger social and cultural purpose. Capitulating wholly to nature rendered men worse than the beasts whose biological urges and impulses they shared. For such a complete surrender to instinct reduced them to degradation and ruin.

Dawson and Lytle agreed that culture was not innate, spontaneous, or automatic. Rather, it arose from the free moral choices that human beings made and for which they had to assume responsibility. “The institution of the family,” Dawson wrote, “inevitably creates a vital tension which is creative as well as painful.”[17] Although a source of dignity, the familial obligations that all members had to perform were also sources of apprehension, misery, and sometimes grief. From the shared perspective of Dawson and Lytle, attempts to evade such strictures in the name of individual liberation brought even more oppressive and harmful consequences in their wake. Culture and civilization began in repression and advanced only through unremitting moral effort. “The complete freedom from restraint which was formerly supposed to be characteristic of the savage life,” Dawson affirmed, “is a romantic myth…. It is the fundamental error of the modern hedonist that man can abandon moral effort and throw off every repression and spiritual discipline and yet preserve all the achievements of culture.”[18] Sexual promiscuity, what Lytle called simply “lust,” was a misplaced and destructive expression of power, the very antithesis of love. The lustful man uses and then discards the object of his desire, taking everything he wants and giving nothing of himself in return. Reciprocal lust deludes and corrupts both partners, resigning them to apathy and desolation.

Only the conventional standards and proscriptions of the family can inhibit the “unrestrained power” of lust that “inflates the ego in all the ways that this kind of power operates.” Lord Acton’s maxim that absolute power tends to corrupt absolutely, Lytle thought at best a partial truth. “Power corrupts absolutely only when it goes beyond formal usage,” he observed, or “when the officer uses the office for his personal ends.”[19] The demands that the Christian patriarchal family imposed ensured that human beings would not be at the mercy of raw instinct and limitless will.

When social and economic conditions favored men without families, men on the move or on the make, men tramping along the roads without direction and with nowhere to go, as in the Greek city states, the late Roman Empire, or Depression America, it was a sign that civilized social order was beginning to unravel. If requisite cultural forms such as the patriarchal family had become too onerous to preserve, then society was certain to lapse into decadence and, worse, into depravity.[20] The ridicule to which marriage and the family were subjected, Lytle, like Dawson, feared, meant not only that civilization would miscarry, but also that countless individual souls would be lost.

Since time immemorial, marriage and family had provided the essential bond between men and women and had bridged the vast chasm between the sexes. That union of husband and wife extended to children, kin, and the community at large, institutionalizing beneficence and responsibility and imaginatively conducting sexual appetite away from all that was pernicious and detrimental. Marriage required that men and women alike subordinate individual desires and sacrifice individual freedoms not to but for each other, and for the common good of both and their offspring. Two thus became one and I thus became we. The spiritual aspects of marriage and the family far exceeded in importance the material. Within the family, members pledged not only their possessions and property to one another, they also promised themselves. The eclipse of the family portended disaster. It meant that persons now stood alone before the world in a conflict of naked power that was sure to devour them, that they would capitulate to the most sinful and destructive aspects of human nature or, at last, that they would succumb to a despair so complete and unrelenting as to lose their faith in God.

Like Dawson, Lytle glimpsed in embryonic form the pathologies that currently infect the family. Both thinkers readily understood that by the 1930s the home had ceased to be the locus of social activity and had instead become a boarding house for vagabonds and wayfarers, who often remained strangers to one another and who rarely even shared a meal. They saw that the state had increasingly replaced parents in supervising and educating children and had circumvented the family in managing and caring for the poor, the infirm, and the elderly. The moral restraints of family life had also been loosed so that “the forces of dissolution” operated without hindrance. Marriage, Dawson lamented, would soon forfeit “all attractions for the young and the pleasure-loving and the poor and the ambitious. The energy of youth will be devoted to contraceptive love and only when men and women have become prosperous and middle-aged will they think seriously of settling down to rear a strictly limited family.”[21] Fifty years later the situation was perhaps worse even than Dawson, for all his prescience, could have anticipated. Not only had men and women delayed marriage, but illegitimacy, cohabitation, and divorce placed the traditional Christian family in jeopardy of extinction. Yet, the problems that the modern family experienced, Lytle said in 1983, were “more symptoms than causes…. The real problem is a lack of love.”[22] Toward the end of the twentieth century, love, incarnated in the abiding union of a man and a woman in holy matrimony, was not longer a precious ideal. It had become for Lytle an existential necessity.

II.

Nathan Bedford Forrest was Lytle’s quintessential southern patriarch. A son of the plain folk, Forrest became an ideal yeoman farmer who worked to make the land fertile and prolific. Early in life, he had already devoted himself to the care and survival of his people. Owning property, managing a household economy, and supporting a family required, for Lytle, acknowledgment of God as the supreme Patriarch. In his way of life, in his understanding that the fortunes of men unfolded according to the divine will, Forrest reaffirmed the patriarchal order of creation. He neither rebuked God nor challenged the nature of things. Although a rugged and untutored backwoodsman, Forrest embodied a piety toward nature and God that was integral to the humane tradition. Properly speaking, Lytle did not advance a vision of civilization, since his protagonists, such as Forrest, did not live in cities, but rather on farms or in the countryside. Instead, Lytle put forth an ideal of pious reverence and submission toward the Creator and His handiwork. He saw the triumph of mind over nature as a kind of progress, for he had no wish that humanity remain backward, mired in primitive superstition and fear. Yet, Lytle also knew that the application of mind to the stubborn and impenetrable aspects of nature was perilous if men went too far, as they always did, and became forgetful of their creaturely nature. Hence the need for a pious outlook to suppress the untrammeled reason and will, which, Lytle thought, were characteristic of modernity.

Forrest did not abdicate his role as patriarch when he enlisted in the Confederate army during the Civil War. On the contrary, he expanded it. Lytle portrayed him as a father figure to those serving under his command. When, for example, Generals John Floyd, Gideon Pillow, and Simon Bolivar Buckner surrendered Fort Donelson, Forrest refused to comply. He had no intention of capitulating, Lytle wrote, having “promised the parents of his boys to look after them.” He “did not intend to see them die that winter in prison camps in the North.” Forrest’s attachment to, and affection for, his men, Lytle elaborated, conveyed the image of a stern but loving parent. He “watched over” his charges, and “assured them that he would not take any needless chances with their lives.” His demeanor “somehow maintained the feeling that the South was one big clan, fighting that the small man, as well as the powerful, might live as be pleased.”[23] Forrest made every provision for the welfare and comfort of his men, even as he expected them to risk their property and their lives, just as he had, to defend their homeland. He disciplined and led not through fear alone, as did his adversary Braxton Bragg, but rather through fear transmuted into respect and love. Unqualified fear, Lytle proposed, was a questionable and precarious form of authority. Forrest retained the allegiance of his troops because experience had taught them to trust his judgment as a general and as a man. He needed neither to punish nor reward them, to treat them with severity or with indulgence. He needed only to command them, for they revered him with “the nearest approach men ever go in deifying one of their own kind.”[24] They had subordinated their wills to his and had entrusted him with their very lives.

Much of Lytle’s fiction, such as his short story “Mr. MacGregor,” examines the moral and emotional disturbances that issue from the collapse of the sort of patriarchy that Nathan Bedford Forrest embodied. Among the most grievous consequences was that the family in any meaningful sense ceased to exist. Individual members came to indulge their private whims and desires, an act that stirred not liberation but brought sickness unto death. Bewildered, crippled in body, mind, and spirit, and thereby diminished, the men and women who populate the world of Lytle’s family romances stumble blindly through their dark predicament. They abandon all measure and restraint. They submit to their appetites and their compulsions. They assert their wills and gratify their egos. They lose themselves and sacrifice all that they love, all that God has entrusted to their care.

Even humane sentiments become distorted and pernicious. Originally published in 1935, “Mr. MacGregor” tells the story of a functional but degenerate patriarchy.[25] The plot centers on the domestic relations of Mr. MacGregor and his wife, over whom he asserts his mastery, trying to dominate all aspects of her life. She, in turn, contests his power and resists his will. When he punishes her slave, Della, for impudence, she defies him: “Mister MacGregor…,” she cautions, “you’re not going to punish that girl. She’s mine.” Undaunted, MacGregor confirms his prerogatives as the head of the household to exercise limitless authority, retorting “And so are you mine, my dear.”[26]

If Della becomes the proxy through which Mr. MacGregor censures his wife for her rebellion, Della’s husband, Rhears, becomes the surrogate through which Mrs. MacGregor seeks vengeance on her husband. Acting in behalf of his wife and himself, but also of Mrs. MacGregor, Rhears calls their master to account. Grown now to adulthood, but in a state of arrested emotional and moral development, the couple’s son describes the events that transpire:

Rhears warn’t no common field hand. He was proud, black like the satin in widow-women’s shirt-waists, and spoiled. And his feelens was bad hurt. The day before, pa had whupped Della and Rhears had had all night to fret and sull over it and think about what was be-en said in the quarters and how glad the field hands was she’d been whupped. He didn’t mean to run away from home like any blue-gum nigger. He jest come a-marchen straight to the house to settle with pa before them hot night thoughts had had time to git cooled down by the frost.[27]

Rhears faces Mr. MacGregor in solitary conflict that can end only in the death of one or the other.

Both his slaves and his wife are extensions of MacGregor’s will, or at least he so regards them. Although suspicious of abstract theory, Lytle characterized relations between master and slave, to say nothing of those between husband and wife, in much the same way that G. W. F. Hegel had. Earlier political philosophers, such and Thomas Hobbes and especially John Locke, had removed slavery to the periphery of social order and human nature. For Hobbes, slavery presented an alternative to death for the loser in the contest between two belligerents. Slavery thus rested on a mutual agreement or contract between the master, who had spared the slave’s life, and the slave, who, as a consequence, owed the master obedience. Locke reasoned that the social compact protected men from enslavement, “the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, Arbitrary Will of another Man.” Yet, should a man violate the social covenant he could forfeit either his life or his liberty without suffering injustice. Slavery was war by another name. “The perfect condition of Slavery,” Locke declared, “is nothing else but the state of War continued, between a lawful Conqueror, and a Captive.”[28] Like Hegel, Lytle established slavery at the heart of the human condition.

In “Mr. Macgregor,” Lytle, perhaps unwittingly, applied this Hegelian definition of slavery. Life consisted of uncompromising and often ruthless warfare among men as well as between men and women. To confirm his identity as a victor and master in that endless strife, Mr. MacGregor requires the conscious submission of his wife and his slaves to his implacable will. They must obey him absolutely and without question, or else they compromise his status. MacGregor has thereby inadvertently rendered himself dependent on his subordinates. As in Hegel’s analysis of slavery, MacGregor both finds and loses his being in the consciousness of another—a consciousness that he can never acknowledge as independent of his own—whether it is that of his slave, Rhears, or his wife. As Hegel ascertained:

The master is the consciousness that exists for itself; but no longer merely the general notion of existence for self. Rather, it is a consciousness existing on its own account which is mediated with itself through another consciousness, i.e. through another whose very nature implies that it is bound up with an independent being or with thinghood in general.[29]

MacGregor is imprisoned by his own power, and cannot obtain autonomy or independence.

Having risked death to attain his position, MacGregor answers Rhears’s insult by reaching for his gun, but Mrs. MacGregor intervenes. She will not permit Rhears, her champion, to be shot like a dangerous criminal or a mad dog. Yet, in her mind, Rhears is not a man, but an extension of her will, a weapon for her to manipulate in the battle with her husband. “There she was,” the narrator, her son, recounts, “one hand tight around the gun stock, the othern around the barrel. Her left little finger, plunged like a hornet’s needle where the skin drew tight over pa’s knuckles, made the blood drop on the bristly hairs along his hand; hang there; then spring to the floor. She held there the time it took three drops to bounce down and splatter. That blood put a spell on me.” MacGregor intuits his wife’s purpose. He yields with “a low bow,” and prepares to fight Rhears with the wits and the strength that God gave him, and to stand or fall accordingly.[30]

Grappling with Rhears, MacGregor produces a knife from his pocket and stabs his adversary to death. The violence is at an end. His wife submits, hands him the gun, the symbol of his power, and he returns it to its place above the mantle. She then proceeds to tend his wounds, orders Rhears’s body to be removed from the house, and suggests that it would be best to sell Della to Colonel Winston when he passes through on his way south. MacGregor has prevailed in the confrontation with his slave, besting him in mortal combat. In so doing, he has reasserted his manhood, his valor, and his predominance. The proper order, it seems, has also been restored between a man and a woman, a husband and a wife, who had “the name of be-en a mighty loven couple.”[31] Yet, appearances deceive, or at least conceal as much as they disclose.

When MacGregor kills Rhears, he does not kill a slave. Whatever the intentions of Mr. and Mrs. MacGregor, Rhears has temporarily become a man, the equal of MacGregor in prowess and courage, and who very nearly triumphs. At the outset of their fight, Rhears no longer acknowledged MacGregor as his master. When he knocked on the door of the big house, he asked to see “Mister MacGregor.” Although ambiguous, his dying words obscure even as they substantiate the change in their relation. “Marster, if you hadn’t got me, I’d a got you.”[32] In his willingness to die, Rhears ceases to be MacGregor=s humble and pliant bondman. No longer overcome by weakness and fear, Rhears proclaims his humanity and his manhood. In that moment, he becomes free, though he pays for his audacity with his life. Conceivably, the dispute might have produced a different result, with the master bleeding to death on the floor of his own house. In that event, Rhears, whom the narrator has already identified as “a powerful, dangerous feller,” would have become the dominant and threatening presence, even as Mrs. MacGregor, who would “rather manage folks than eat,” tried again to subjugate him.[33] The meaning of authority and subordination, of sovereignty and compliance, of freedom and slavery, are far more complex and elusive than either Mr. or Mrs. MacGregor imagine.

All human relations are relations of power, fraught with a tension that can at times become murderous. Yet, the deeper significance of “Mr. MacGregor” lies in the story that Lyle does not fully tell—the story of the MacGregors’ son—and what it portends for the future of the Christian family and traditional social order. The man who, as a boy, witnessed the vicious contest of wills between his father and mother, between a master and a slave, has wrecked his life with drink. Never having recovered from the spell his father’s blood cast over him, he has wandered through life a bewildered soul, a perpetual child, at once jealous of his lost innocence and evading the knowledge that accompanies maturity. He repeats the tale whenever he is “taperen off,” for it is then that “a man gits melancholy and thinks about how he come not to be president and sich-like concerns. Well, sir, when I’d run through all my mistakes and seen where if I’d a-done this instead of that how much better off I’d be today, and cuss myself for drinken up my kidneys, I’d always end up by asken myself why that woman acted like that.”[34] The narrator’s parents have reconstituted, or acquiesced in, patriarchy, but their method was so rife with discord, confusion, and violence that their son has never regained his moral equilibrium. He inherits only confusion and tumult, discerning but unable to explain his perplexity:

You might almost say pa had whupped ma by proxy. And here was Rhears, again by proxy, to make him answer for it… a nigger and a slave, his mistress’s gallant, a-callen her husband and his marster to account for her. I don’t reckon they’d been any such mixed-up arrangement as that before that time; and I know they ain’t since.[35]

With “Mr. MacGregor,” Lytle discerned that not the sins only but also the virtues of the past can befoul the lives of the next generation.

This essay was originally published at The Imaginative Conservative.

[1] Andrew Nelson Lytle, From Eden to Babylon: The Social and Political Essays of Andrew Nelson Lytle (Washington, D.C., 1990), 77.

[2] Ibid., 90.

[3] Ibid, 77.

[4] Andrew Nelson Lytle, A Wake for the Living (Nashville, TN., 1992, originally published in 1975), 269.

[5] From Eden to Babylon, 241.

[6] A Wake for the Living, 158.

[7] Christopher G. Memminger, Slavery Consistent with Moral and Physical Progress (1851), quoted in William Sumner Jenkins, Pro-Slavery Thought in the Old South (Gloucester, MA, 1960), 210. See also Mark Malvasi, “The Old Republic and the Sectional Crisis,” Modern Age 49/4 (Fall 2007), 469.

[8] A Wake for the Living, 134-35.

[9] Andrew Nelson Lytle, Southerners and Europeans: Essays in a Time of Disorder (Baton Rouge, LA, 1988), 119, 120. On the southern family and its patriarchal relations, see Catherine Clinton, Plantation Mistress: Woman’s World in the Old South (New York, 1984); Steven M. Stowe, Intimacy and Power in the Old South: Ritual in the Lives of the Planters (Baltimore, 1987); Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Within the Plantation Household: Black and White Women of the Old South (Chapel Hill, NC, 1988); Joan E. Cashin, A Family Venture: Men and Women on the Southern Frontier (Baltimore, 1991); Brenda E. Stevenson, Life in Black and White: Family and Community in the Slave South (New York, 1996); Craig Thompson Friend and Anya Jabour, eds., Family Values in the Old South (Gainesville, FL, 2010).

[10] Southerners and Europeans, 122.

[11] Ibid., 118.

[12] Ibid., 123, 120.

[13] Christopher Dawson, “The Patriarchal Family in History,” in The Dynamics of World History, ed. by John J. Mulloy (Wilmington, DE, 2002), 168. Dawson’s essay was originally published in 1933. On Dawson’s analysis patriarchy, see R.V. Young’s superb “A Dawsonian View of Patriarchy,” Modern Age 49/4 (Fall 2007), 417-24.

[14] Southerners and Europeans, 139.

[15] Dawson, “The Patriarchal Family in History,” 166.

[16] Southerners and Europeans, 301.

[17] Dawson, “The Patriarchal Family,” 168.

[18] Ibid., 167, 168.

[19] Southerners and Europeans, 9.

[20] Dawson concluded that the patriarchal family had “failed to adopt itself” to the “urban conditions” of ancient Greece and Rome. See “The Patriarchal Family in History,”169-70.

[21] Ibid., 173.

[22] From Eden to Babylon, 240.

[23] Andrew Nelson Lytle, Nathan Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company (Nashville, TN, 1992, originally published in 1931), 86, 149.

[24] Ibid., 55.

[25] The story appeared in the April 1935 issue of The Virginia Quarterly Review, and was Lytle’s first published short story. I have used the version reprinted in Andrew Lytle, Stories: Alchemy and Others (Sewanee, TN, 1984), 51-64. See also Madison Jones, “A Look at `Mister McGregor’” [sic], in M.E. Bradford, ed., The Form Discovered: Essays on the Achievement of Andrew Lytle (Jackson, MS, 1973), 17.

[26] “Mr. MacGregor,” 59.

[27] Ibid., 55.

[28] Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, ed. by Michael Oakeshott (New York, 1962), 153-55 and John Locke, Two Treatises of Government, Revised Edition, ed. by Peter Laslett (New York, 1965), 297-302, 341. Italics in the original.

[29] G.W. F. Hegel, The Phenomenology of Mind, trans. by J.B. Baillie, 2nd ed. (New York, 1964), 234-35.

[30] “Mr. MacGregor,” 55-56.

[31] Ibid., 58.

[32] Ibid., 64.

[33] Ibid., 54, 56.

[34] Ibid., 57.

[35] Ibid., 60.

A minor correction: The fifth commandment is to honor father and mother… the Roman Church follows the tradition of making it fourth and murder fifth, but that would have been foreign to any American citizen in the mid nineteenth century.