In the warped minds of today’s so-called “woke,” even such an evocative holiday song as Irving Berlin’s “I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas” can take on a far different connotation than when Bing Crosby sang it eight decades ago. Going back much further in time, the simple “OK” hand gesture which has been in use around the world for well over two thousand years, and with numerous benign meanings, is now considered by the politically correct to be a signal of white supremacy.

With this in mind, imagine what the reaction would be today if some politician stood before a crowd of ten thousand people in an American city and charged that the federal government was attempting to give special rights to black Americans by depriving white Americans of their rights. Tweets of liberal outrage would go viral in seconds and within hours, groups such as the Southern Poverty Law Center, or even the federal government, would be beating a path to that person’s door to post upon it notices of “racist” and “white supremacist.”

While no person in their right mind would now consider making such remarks in public, in 1863 a well-known Democratic politician did just that . . . and it was not uttered in the South by some Confederate fire-eater, but in Ohio by a man who had been a United States congressman from that State until just a month prior to making his speech. The orator was Clement L. Vallandigham, and his address was given on May 1st in the central Ohio city of Mount Vernon. In violation of his First Amendment right of free speech and despite the fact that he was a civilian, Vallandigham’s remarks led to Union troops breaking into his residence a few days later and arresting him at gunpoint in front of his terrified wife. He was tried the next day by a military tribunal, convicted the following day and sent immediately to a military prison in Boston for the duration of the War.

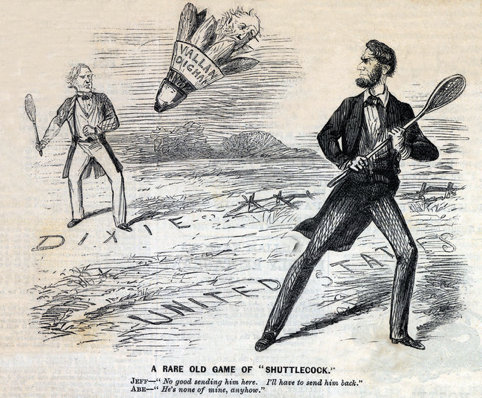

After an appeal for a right of habeas corpus that was filed on Vallandigham’s behalf by former United States Senator George Pugh of Ohio was denied by a federal court, protests against such unconstitutional actions and military despotism from Pugh, Governor Seymour of New York and other prominent Northerners were immediately sent to President Lincoln. Not wishing to turn Vallandigham into a martyr, Lincoln released him and ordered his deportation to the Confederacy.

Realizing the political implications of Lincoln’s move, President Davis soon put Vallandigham aboard a blockade runner bound for Bermuda. From there, he ultimately made his way to Canada where he ran his unsuccessful campaign for governor of Ohio after the state’s Democratic Party had nominated him in absentia by an almost unanimous vote. As a footnote, later that same year, the incident inspired author and historian Edward Everett Hale to write his famous short story “The Man Without a Country.”

Vallandigham’s political career had begun in 1845 as a member of the Ohio State Legislature and while in that chamber, he had voted against amending the State’s “Black Laws” that barred blacks from voting, holding public office, acting as a juror or testifying against a white person in court and serving in the state militia. In an effort to discourage blacks from settling in Ohio, the laws also required them to post a five hundred dollar bond (almost $18,000 today) before moving to the State, as well as registering proof of freedom before seeking employment. Prior to 1848, the laws also prohibited blacks from entering the public school system and after that date, they could only attend segregated schools. Some of the laws were modified before the War Between the States, but they were not completely abolished until 1887.

Not only Ohio had such laws, however, as several other Northern states, including Abraham Lincoln’s home state of Illinois, had similar legal restrictions agains blacks. Likewise, public opinion in the North, even that of Lincoln himself, did not accept the concept that the phrase “all men are created equal” actually meant that the black race was equal to the white. Many in the North were, like Vallandigham, personally opposed to the institution of slavery per se but still maintained that since it was legal under the Constitution, those in the South should be permitted to own slaves, as well as determining their own course of action in regard to emancipation. Most such people also felt that while the nation’s black population had certain legal rights, they were still an inferior race and should be treated accordingly or, like Lincoln, relocated to Africa or some other place outside the United States.

Examples of such nationwide bias can be found in many aspects of past American life such as education, employment, housing and even personal relationships. In the 1800s, virtually all public schools in the North remained segregated, if not by law then on a de facto basis, with only a few, such as those in Lowell, Massachusetts, that finally accepting black students in 1843. In schools of higher education, while a number of black colleges and universities were established in the South after the War Between the States, there were only four in the North prior to the War. The first in 1837 was Cheyney College in Pennsylvania and the next in that state was Lincoln University in 1854. Two years later, Wilberforce University and Payne Theological Seminary were both established in Ohio. In addition, a small school for black girls, the Miner Normal School, was opened in the nation’s capital in 1851, a school that ultimately would become the University of the District of Columbia. The first and perhaps only biracial school of higher learning in America during the antebellum period was Oberlin College in Ohio which decided to admit black students two years after its founding in 1833 and from which the first black student was graduated over a decade later.

Except for the blacks that operated their own businesses, employment for the majority was also highly restricted throughout America until well into the Twentieth Century. For black women, the only employment available was in the domestic and personal services, as well as low-paying factory jobs in various textile industries. Except for those working as day laborers or field hands, it was much the same for black men. One field that offered more opportunity for black males was the building and operation of railroads in both the North and South, but at far lower wages than their white counterparts.

By the late 1800s, however, most blacks in railroading were being replaced by whites, with the only exception being what was to become an exclusively black occupation, sleeping-car porters for the Pullman Company. Most Northern labor unions also excluded blacks from their membership and as late as the 1950s, even radio stations, including those in the North, required that people applying for jobs by mail had to include a photograph with their résumé. It should be remembered as well that strict segregation also remained a part of United States military service until 1948.

While black housing and access to public facilities was a matter of state legislation in the South until the end of the so-called “Jim Crow” era over half a century ago, the de facto exclusion of blacks in the North was also the rule for an even longer period of time. There, most private clubs barred blacks from membership and many business establishments openly discouraged black patronage. The same held true in such sports as major league baseball. While one black player, William White, played as a substitute first baseman in a single National League game in 1879 and two others, Moses and Weldy Walker, played during the 1884 season in what was then called the American Association, there were no other black players in the major leagues until Jackie Robinson was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947.

In housing, most communities in the North were largely divided along strict racial lines and blacks generally found it virtually impossible to locate homes in white neighborhoods. Following World War Two, New York real-estate developer William Levitt became the father of modern suburbia with his massive Levittown that was started on New York’s Long Island in 1947. Levitt wanted to make America’s dream of having one’s own home become a reality for the seventy thousand people that would inhabit his new community. It was, however, a dream exclusively for white America, with black Americans being barred from entry. All Levittown housing documents contained the stipulation that the property would not be “occupied by any person other than members of the Caucasian race.” The same discriminatory rule also held true for the Levittown built in Pennsylvania in 1953 and the one in New Jersey five years later.

In 1955, the NAACP had brought an action to have the federal government force an end to Levitt’s discriminatory practices, but the court dismissed the suit on the grounds that federal agencies could not prevent housing discrimination. Two years later, the owners of a home in the Pennsylvania Levittown sold their house to a black family who were harassed and threatened for months by their white neighbors with little or no help from the local authorities.

The Levittown incident was certainly not unique and even though the Supreme Court had ruled as far back as 1917 that residential segregation laws were unconstitutional, such restrictions were still practiced throughout the country until the full implementation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. As late as the 1930s, when President Roosevelt created the Home Owners Loan Corporation, the agency had a system for granting mortgage loans that became known as “redlining” in which white neighborhoods were given the highest loan priority and those with an “undesirable element” (i.e., blacks and other minorities) the lowest. The same type of discriminatory standards were also used by the Federal Housing Authority for many years thereafter.

In the matter of personal relations between whites and people of other races, the Virginia Colony passed America’s first anti-miscegenation law in 1691 that barred a white person from marrying someone of another race. This type of law, however, was soon followed by two colonies in the North, Massachusetts in 1705 and Pennsylvania in 1725. Unlike Virginia, the Pennsylvania law only specified blacks, while the Massachusetts law also included American Indians. Over the ensuing years, thirty-eight other states in both the North and the South enacted similar types of laws regulating interracial marriage. While the seventeen former slaveholding states were forced to abolish their laws following the Supreme Court’s 1967 Loving vs. Virginia decision which ruled that such laws violated the Fourteenth Amendment, eleven Northern states did not repeal such acts until the years from 1843 to 1887 and another thirteen did not do so until the following century, with the last two being Indiana and Wyoming in 1965.

As unpalatable as such actions may seem today, slavery and blatant discrimination against blacks and other minorities, along with the general attitude of white supremacy on the part of Northerners, as well as those in the South, were all chapters in America’s history until well into the Twentieth Century. To deny this is to deny history, much the same as when Hitler sought to erase the thoughts of those who did not agree with his philosophies by burning their books.

Any sensible individual might now agree that it is perfectly acceptable to try and explain the reasoning behind such past acts of intolerance in the context of today’s social mores. However, they should also then be willing to agree that it is totally unacceptable to claim that since such events should not have taken place at all, they must therefore be forever erased from history’s pages and, as in Orwell’s “1984,” replaced with more politically correct concepts.

2 Comments