“Remember therefore from whence thou art fallen, and repent, and do the first works; or else I will come unto thee quickly, and will remove thy candlestick out of his place, except thou repent.”

—Revelation 2:5

The Attack on Confederate Monuments is a subspecies of what Richard M. Weaver called the “attack on memory.” To understand why the attack on memory is a necessary part of the project of modernity is to understand why that attack will never relent, even after the last unassuming plaque honoring the Confederate dead is gouged out of a walkway and Robert E. Lee’s bones are dug up from underneath the former Lee Chapel to be ground into powder and fed to jackals. By understanding the pervasive nature of this attack we may know more deeply the importance of memory, especially the way it forms and shapes love and loyalty, as well as how we might begin to recover our memory for ourselves and our children, and thereby rebuild a society that encourages virtue according to Divine design.

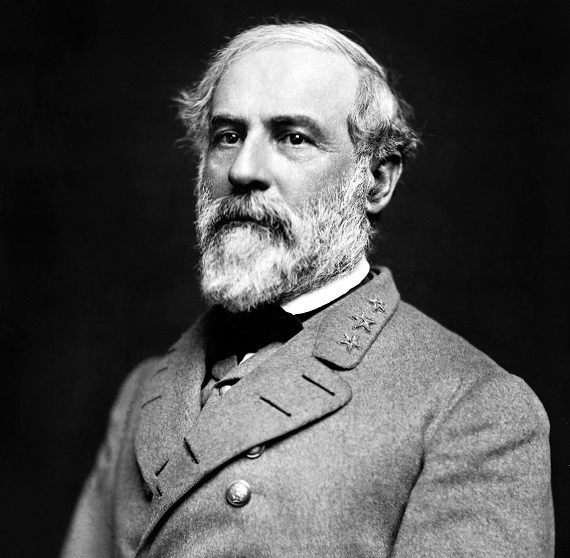

First, let us look at some “facts.” The most celebrated destruction of Confederate monuments dedicated to a particular person involves those memorializing Robert E. Lee, the man who once gave Southern boys, and even Southern girls, their middle names. (My youngest is Peter Ambrose Lee Wolf.) Robert E. Lee was a Christian—a low-church Episcopalian—as well as a professional soldier. He inherited and owned slaves and freed slaves. He resigned his commission in the U.S. Army and commanded what was eventually called the Army of Northern Virginia. More facts: By his own word he hated slavery, thought it bad for the Negro race and worse for whites. And by his own word he loved the Union and despised secession.

These are, as I said, “facts.” There are, of course, many more true statements we could make about Lee—about his lineage, details about his service to his country. It is actual and factual that Lee wrote what follows in a letter to his sister, explaining why he hadn’t been able to visit her in the spring of 1861:

The whole South is in a state of revolution, into which Virginia, after a long struggle, has been drawn; and though I recognize no necessity for this state of things, and would have forborne and pleaded to the end for redress of grievances, real or supposed, yet, in my own person, I had to meet the question, whether I should take part against my native State.

With all my devotion to the Union, and the feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home. I have, therefore, resigned my commission in the army; and save in defence of my native State, with the sincere hope that my poor services may never be needed, I hope I may never be called on to draw my sword.

Look at the words: The man whose equestrian statues so many of us are inclined to defend, and so many others are foaming at the mouth to destroy, was not an ideologue of secession. He had particular concerns and convictions about it even after Abraham Lincoln’s election, the secession of several states, the formation of the CSA, the drafting of the Confederate Constitution, and the election of Jefferson Davis. This letter to his sister was written from Arlington just over a week after Fort Sumter, and three days after Virginia issued her Ordinance of Secession. Even then, he spoke of the South’s grievances as “real or supposed.” Even then he spoke of his “devotion to the Union.” Even then, he understood that an American citizen has a duty, and his affections were virtuously habituated toward that duty.

He had a “feeling of loyalty.”

Duty, however, is not rooted in abstract ideas, no matter who claims they are self-evident. Duty is man’s obligation to pursue the good according to his station in life within the Created Order. And duty to the federal government dissolves when that government threatens to raise its hand against relatives, children, and home. How could there be virtue in drawing your sword against your family and your native state? And, more to our point, why would a monument to such a man, a man about whom the above-mentioned facts are indisputable, cause such great and sudden seizures of offense?

Here is Jesse Jackson’s response: “There are no Hitler statues in Germany today or neo-Nazi material [sic] flying around. These guys sought to secede from our union, maintain slavery and secession and segregation and sedition, and so these statues are coming down and they should come down.”

Such a stupefying statement, whose sentiment is shared by writers in major newspapers, politicians, university professors, public-school teachers, denominational leaders, and a growing army of snowflakes, cannot be met with facts, even though we might be tempted to offer some once our blood returns from rolling boil to simmer. For we must remember something that we, for too long, have forgotten: Facts themselves are meaningless.

“‘Facts’ do not exist by themselves—surely not in our minds,” writes John Lukacs (At the End of an Age). “There is no such thing as an entirely independent, or isolated, or unchanging fact. Any ‘fact’ is inseparable from our association of it with another ‘fact’ (and in our minds this association is necessarily an association with a preceding fact). Any ‘fact’ that is beyond or beneath our cognition, or consciousness, or perception, is meaningless to us—which is why we must be very careful not to dissociate ‘facts’ from the way in which they are stated.”

I bring this up here for a reason. Every time another Lee monument is torn down, the newspapers, magazines, and websites take another turn at calling him a traitor, and condemning him and everyone who might admire him as a racist. On that dark day at Lee Circle in New Orleans when his monument was clumsily brought down by masked men on a crane, I engaged in an online debate with a Republican editorialist about the character of Lee. Why, he wondered, would anyone want to memorialize this monster, whose image could call to mind nothing but the scourge of slavery and the hatred of black people? How could any American defend a man who had fought against the Federal Army of the United States? (His eyes had seen the glory.) I challenged him with facts. I mentioned Lee’s stated dislike of slavery. I mentioned his turning down of a commission in the CSA, before Virginia seceded. I quoted the aforementioned letter in which Lee outlined his reasons for resigning his commission and clarified his understanding of duty. I mentioned Lee’s insistence to his men and to anyone who would listen, after the War, that peaceable relations be pursued. I mentioned that Lee declared his happiness at the thought that slavery had ended. None of these facts mattered. Actually, it was worse than that: The facts proved his point.

Lee’s very understanding of an ordered reality and a man’s corresponding duty within it was outrageous to my Republican opponent, even as it was to Ulysses Grant, as Grant stated in his memoirs. But paradoxically, Grant was more sober than this 21st Century Republican. Grant maintained deep respect for Lee; my GOP debater thought he should’ve been hanged.

With each new episode of the ongoing Attack on Southern Symbols, some scribe among America’s Pharisees will trot out quotations from General Lee in which Lee himself indicates his disapproval of monuments to the Confederacy—again, in the interest of peace. “Robert E. Lee opposed Confederate monuments” rang the title from PBS in the wake of last year’s shameful disaster at Charlottesville. In its treatment of Lee, the article is mild compared with the standard article that has emerged over the last decade, which must always include the word traitor. PBS does not call him that. But PBS does suggest as much, rehearsing his list of sins, which, in our Manichaean world of free-floating facts, comprises everything he ever did, including, remarkably, his sin of succumbing to a stroke. “Lee died in 1870,” PBS states, “contributing to his rise as a romantic symbol of the ‘lost cause’ for some white southerners.” The voicing and tense of the verbs imply that even Lee’s death was an act of rebellion, providing singularly racist Southerners—white Southerners, you will note, servants of the Demiurge—with the inspiration they needed suddenly to redefine a war they knew they fought solely for the brutal oppression of Negroes, transforming it after the fact into an effort to preserve states’ rights and protect their homes and hearths. Lee had a stroke so that he might create the Myth of the Lost Cause.

PBS even invites speculation on Lee’s motives for opposing monuments to the Confederacy. It cites Lee biographer Jonathan Horn:

“You think he’d come down in the camp that would say ‘remove the monuments,’” Horn posited. “But you have to ask why. He might just want to hide the history, to move on, rather than face these issues.”

Jonathan Horn was also a speechwriter for George W. Bush. The Bush administration did not lack for diversity. Condoleezza Rice has come down on the opposite side of the debate over Southern monuments. She has gone on record as opposing the destruction of Southern monuments, on the grounds that keeping them up and in place is necessary in order for us to avoid the sin of “hiding the history.” In her estimation, “hiding the history” means “sanitizing” it, depriving the public of the requisite and constant reminder of slavery that is needed for us to continue “expanding our definition of ‘we the people.’” Monuments to slave-owners like Lee inspire us to maintain our struggle as Americans to live up to the “American Creed,” which for Secretary Rice is the “aspiration” of progress, and includes as its very “lifeblood” an invitation to the world to participate in it. So the “fact” called to mind when we see Lee atop Traveller is that there is no American people, only an idea.

Secretary Rice’s view is the minority view, although it is about the only defense the American Right seems capable of mounting against the refurbishing of America’s public spaces in this Age of Image and Ideology. The process is now routine. The Left demands the removal of a Southern symbol, in the name of social justice and equality. The Right demurs, attempts to be conservative, and responds, “Who’s next—Jefferson? Washington?” The Left agrees that Jefferson and Washington will indeed be next, but first things first. The Right then remembers that Congress is reelected every two years, that conservative writers like to appear on panels on the Sunday shows, that the Klan was Democratic, and that Lincoln was a Republican; and so the Right agrees that the Southern symbol must go, in the name of social justice and equality. The demolition proceeds, the flag is lowered, and Nikki Haley is promoted to the United Nations. Both sides, out of ignorance or malevolence or both, seek to “hide the history.” For ultimately, both sides seek the “end of history.”

The “end of history,” as Francis Fukuyama portentously termed it, was supposed to come about through the spread of liberal democracy, which, by the lights of Condoleezza Rice, George W. Bush, John McCain, and Bill Kristol, no people worth keeping alive would turn down. The nations of the world will adopt liberal democratic governments, with the United States as the lead domino, and there will be no basis for any other government to arise. Others, of the Marxist/Antifa/Bernie bent, would see history’s end in a socialist workers’ paradise where no one goes to work and everyone attends free community college and Harvard Law School. Their history ends in John Lennon’s “Imagine.” (It was odd during the 2018 Winter Olympics to witness ice dancers representing the United States gliding and twizzling to the line “Imagine there’s no countries / I wonder if you can,” in an arena two hours from the DMZ.) Both Right and Left have the end of history as their imagined goal, and govern accordingly, each attempting to create and impose new federal laws that will align the lives of 350 million people with the fabled “American Creed,” in which the hypostatic union includes the sacred word indivisible. But for there to be a Left and a Right, there must be a spectrum, and that spectrum has a red shift. It has always been this way, ever since the Left and the Right emerged during the French Revolution, following an act of regicide. With our so-called Civil War, it followed fratricide.

For there to be an “end of history” in the teleological sense, there must be an end put to history qua history. The nationalist history of America invented by Abraham Lincoln during his campaign for the presidency and handed down to the ages in the cloying rhetoric of the Gettysburg Address was the Found Cause of the Union. Its one virtue was that it allowed some room for public Southern symbols, because the Found Cause needed its Lost Cause for the clarification of doctrine. Lee could be mistaken, yet valiant and worthy of emulation. His duty could be deemed disordered, but righteously pursued. Loyalty to family and native state and region must bow to nation and perpetual union. And so, in the old nationalist history, Lee’s duty could be abstracted and assimilated. The Confederate Battle Flag could be co-opted by neo-Klansmen in 1920’s Indiana, even as it is now waved by white-nationalist Nietzchean youth under the banner of the Alt-Right, goose-stepping around the Lee monument in Charlottesville. (It was revealing to see video footage of Richard Spencer reading the lyrics of “Dixie” off a cellphone to a busload of fashy-haired clones on their way to that rally. None of them knew the words. They were not in their memory.) But, “the nationalist history was fake,” as Clyde Wilson wrote in Chronicles, in an article adapted from a speech he gave at the John Randolph Club upon receiving the Good and Faithful Servant Award.

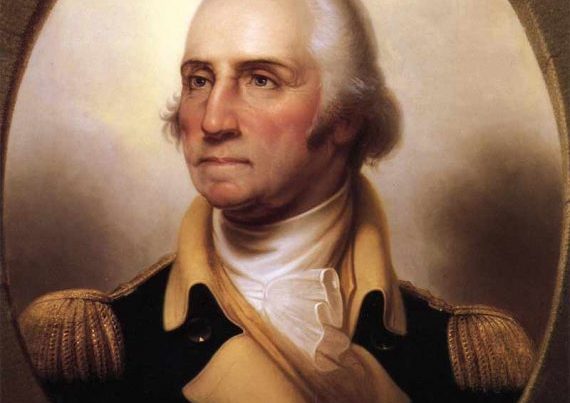

The nationalist history was fake. It was really the history of New England Yankees, and it ignored, slandered, or coopted the stories of other Americans. Early on, the “intellectuals” of Massachusetts set out very deliberately—and you can document this with great specificity—to make the American story their exclusive property. After the War to Prevent Southern Independence, their mission was complete. The proud fox-hunting Virginia planter George Washington was turned into a prim New England saint, and the heroes of the Alamo were coopted for Lincoln’s war on the South. To explore how Bostonian “American” history became multicultural/“gender” history would take many pages. I will only say that the two things are more closely related than many are willing to admit, just as debauchery and Puritanism are two sides of the same coin. But at least the old nationalist history had a limited fungibility. The new history has no redeemable value whatsoever.

Indeed the two histories are closely related, and I would argue that the Right’s nationalist history was predestined, so to speak, to give way to the Left’s internationalist ideology, which cannot really be described as history at all. It is the systematic attack on memory itself, disguised as history. For history requires what John Lukacs calls “historical consciousness.” (No one “witnesses history”—a phrase often spoke today. For example, we were supposedly “witnessing history” when the Supreme Court declares that sodomy is marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges.) History is the “remembered past,” remembered according to values and virtues that are the inheritance of a particular people. The story as told gives meaning to the “facts,” and the story must be told to be remembered.

“Amnesia as a goal is a social emergent of unique significance,” writes Richard Weaver (“The Attack Upon Memory,” Visions of Order). “I do not find any other period in which men have felt to an equal degree that the past either is uninteresting or is a reproach to them. When we realize the extent to which one’s memory is oneself, we are made to wonder whether there is not some element of suicidal impulse in this mood, or at least an impulse of self-hatred.” I would include the influence of the diabolical, for the impulse to be “as gods” begins with the serpent’s lie in the Garden and a certain amnesia with regard to what God really said.

What the serpent had not yet perfected in that antediluvian time was technology, the mechanization of all of life that could make possible the mass-consolidation of people, living apart from the natural restraints that hinder evil and habituate virtue. An industrialized society affords many creaturely comforts, including the illusion of unlimited freedom and equality, which are then held forth as goods or ends to be pursued. But to pursue them apart from the bounds of the Created Order is to destroy the created order, and therefore the very possibility of meaning and true joy. (C.S. Lewis and Andrew Lyle both wrote that the “pursuit of happiness” is a fool’s errand; happiness is only found in the pursuit of God, according to the means He has granted.) Thus, amnesia as a goal, the fulfillment of the “end of history,” is a recipe for mass-suicide. The increase in depression, our “opioid crisis,” and our “broken young man” mass shooters are symptoms of the disease of chronic self-loathing.

Andrew Lytle’s book A Wake for the Living defies genre. It is a deep family history written for his daughters, but it is also a narrative thesis on memory itself. It is remarkably hilarious and at the same time devastatingly poignant, showing us (as his chapter “The Hind Tit” did in I’ll Take My Stand) how much we have lost of the humane society of the South, even after the War and Reconstruction. “If you don’t know who you are,” he writes,

or where you come from, you will find yourself at a disadvantage. The ordered slums of suburbia are made for the confusion of the spirit. Those who live in units called homes or estates—both words do violence to the language—don’t know who they are. For the profound stress between the union that is flesh and the spirit, they have been forced to exchange the appetites. Each business promotion uproots the family. Children become wayfarers. Few are given any vision of the Divine. They perforce become secular men, half men, who inhabit what is left of Christendom.

Lytle continues a paragraph or so later, in a vein similar to Chesterton’s “democracy of the dead”:

If we dismiss the past as dead and not as a country of the living which our eyes are unable to see, as we cannot see a foreign country but know it is there, then we are likely to become servile. Living as we will be in a lesser sense of ourselves, lacking that fuller knowledge which only the living past can give, it will be so easy to submit to pressure and receive what is already ours as a boon from authority.

Only a servile people would view a man’s right to refuse to raise his hand against his family and his native state as a privilege granted him by his government. The head-of-household, the paterfamilias, the Hausvater, does not receive his authority over his family, or his duty to protect them and provide for them, from the state, as a “boon from authority.” They are already his, as gifts from God. The family as God made it, and the sexes as God made them, are inherently and complexly hierarchical, intrinsically unequal according to station, yet equal in human dignity before God. Each member of the household derives meaning and pursues virtue not by eliminating natural distinctions, but by doing his distinct duties. The Father is not the Son, and the Son is not the Father. Yet human equality, that false moral principle of our post-Enlightened age, opposes hierarchy of any and every kind, whether societal and subject to slow change and improvement (as slavery was), or natural and unchanging, as the family is.

Any Southern symbol on public display is a witness against abstract equality. For man is not only sinful by nature but curious, and to witness public art is to have one’s imagination awakened. What does this mean? Who is this man here depicted, and what did he fight for? My friends who honor this statue, this sculpture, this plaque, this flag—they are neither racists nor neo-Nazis. This man said he would not raise his hand against his family. Neither would I . . .

The possibility of man’s perfection in this life and apart from divine grace is the underlying premise of both Left and Right. For that is what is meant by equality, whether it is the Left speaking of the equality of outcome, or the Right speaking of the equality of opportunity. Both mean—must mean—unlimited college tuition, unlimited sexual expression, unlimited “gender identification,” unlimited immigration, and unlimited war. Statistically speaking, a certain population somewhere wants something it feels it is being denied. It wants the dignity of having a college diploma. It wants better healthcare. It wants to “love” whomever it wants to love. It wants people on the other side of the world to be as they are, knowing good from evil.

The pursuit of the perfection of man as mass-man, or mass-human, free of distinction and duty, is the ultimate abolitionism: It seeks the abolition of man. William Jennings Bryan foresaw this in Dayton, Tennessee. Man, as Darwin’s naked ape, behaves like one. Weaver writes that the elimination of memory reduces man to an animal, a creature led about by base instinct, living in an eternal present.

“[W]hen we come to analyze the real nature of time,” writes Weaver,

we are forced to see that the present does not really exist, or that, at the utmost concession, it has an infinitesimal existence. The man who pretends to exist in this alone would cut himself off from almost everything. There is a past, and there is a future, but the present is being translated into the past so rapidly that no one can actually say what is the present. If we say that everything should be for the present, we must quickly divorce ourselves from each past moment and at the same time not attend to those subjective feelings, born of past experience, which are our picture of the future. The richness of any moment or period comes through the interweaving of what has been with what may be. If every moment past is to be sloughed off like dead skin and a curtain is to be drawn upon future probabilities, which are also furnished by the mind, the possibilities of living and of enjoyment are reduced to virtually nothing.

The violent, antinomian, indignant hatred of Southern monuments is understandable and was inevitable, given the rise to dominance of “presentism.” Martin Luther, returning from exile after the Diet of Worms, decried the smashing of stained glass images because it robbed the illiterate of their Bible. The images tell a story. Southern images tell stories, too, which contradict America’s national ideology, an ideology that is difficult to impose because it is unnatural. It is unnatural even for fallen men to hate their wives and children, to murder their brothers. It is unnatural to seek approval from a distant ruler to live life according to the long-held traditions of your people. It is unnatural to ask a president or Congress for permission to teach your own children at home, or to carry a weapon, or to buy milk from your neighbor’s cow. But this is what the American national myth demands. It demands of us that we dedicate ourselves to propositions as religious dogmas, find our identity in the extreme outer reaches of our existence, and turn our feelings of loyalty upside down.

“It is memory that directs one along the path of obligation,” writes Weaver. “License is checked, or at least made self-conscious by this monitory awareness. Therefore if we wish to be free in the unphilosophical sense of freedom, we must get rid of mind. Memories inhibit us and even spoil our pleasures. They keep in sight the significance of our lives, which influences and inhibits action. Under the impossible idea of unrestricted freedom, the cry is to bury the past and let the senses take care of the present.”

Symbols call memories to mind. In reading Weaver, I’m reminded of Paul Overstreet’s song, sung by Randy Travis, about the temptation to adultery, whose chorus says, “But on the other hand / there’s a golden band / to remind me of someone who would not understand.”

The call to repentance in the Old Testament is always a call to remember, to recall to mind not some abstract maxim or idea or rule or dogma, but the living past in which God Himself dealt graciously with the people. Every act of apostasy is a violation of a covenant the LORD made in space and time. To commit adultery, or steal, or bear false witness is to forsake what God wrote with His own hand into Creation, and then again on tablets of stone.

Somewhere in the ninth century B.C., nearly the entire nation of Israel had turned pagan, assimilating to the worship of the gods of their Canaanite neighbors. All of Israel whored after Ba’al and Ashteroth, crafting idols and gathering in sacred groves, giving themselves over to licentiousness and the predations of a foreign-born pagan Queen Jezebel and King Ahab, who “did evil in the sight of the Lord above all that were before him.”

The writer of 1 Kings describes Ahab’s apostasy as a failure to remember: “And it came to pass, as if it had been a light thing for him to walk in the sins of Jeroboam the son of Nebat, that [Ahab] took to wife Jezebel the daughter of Ethbaal king of the Zidonians, and went and served Baal, and worshipped him.”

Elijah the Tishbite remembered. In his supreme act of defiance against his king and an orgy of pagan priests cutting themselves and calling out to an impotent god made in their own image, Elijah called down fire from heaven, vindicating the name of the LORD. Even that involved a plea on behalf of the people’s memory. “And Elijah took twelve stones, according to the number of the tribes of the sons of Jacob, unto whom the word of the LORD came, saying, Israel shall be thy name: And with the stones he built an altar in the name of the LORD.” When he called for the fire, he invoked not simply Jehovah, but the God of their fathers, the “LORD God of Abraham, Isaac, and of Israel.”

The monuments to Robert Edward Lee, and to Stonewall Jackson, and to the Confederate dead in general are not meant to be idols. They are the art and artifacts of memory, the memory of a people who lived in what Weaver called “the last non-materialist civilization of the Western World” (The Southern Tradition at Bay). Those who erected these artifacts lived amid the rubble of that civilization, now gone with the wind. We who are their descendants do not inhabit that civilization. And I would bet that John Lukacs would go further and add that there is no such thing as a materialist civilization, and C.S. Lewis would add that our modern, technocratic, scientistic education system engages in the ironic activity of cultivating barbarism.

Because of that, I am frankly stunned that the Southern monuments have remained for as long as they have. It is a testament to the memory of unreconstructed Southern people, and to what fragments remain of our former system of government, that there remains some drag on the designs of the image-breakers. But the momentum is in their favor. Recently, a District Court Judge dismissed charges against two, and found a third not guilty, for tearing down and desecrating a Confederate monument in Durham, North Carolina. They had done this in broad daylight, recorded it on video, and posted it on the World Wide Web. Defense attorneys argued that the action was just, despite the clear violation of the law, because the statue was a “symbol of white supremacy and an affront to the Constitutional right to equal protection under the law” (WRAL.com). Outside the courtroom the newly acquitted vowed to press on. “Sometimes folks have to take risks to challenge unjust laws.”

Robert E. Lee, as I said earlier, did indeed caution against the erection of monuments to the Confederacy, in the interests of peace. After Reconstruction, the nationalist doctrine allowed for some degree of coexistence, provided that Southerners stayed in their place, and the symbolism of the Confederacy could be displayed publicly and ignored by those who disagreed. But that day is now over. Today, nationalism itself is reinterpreted as patriotism by the Right, and tarred and feathered as racist by the Left, with Southern symbols, stripped of memory and meaning, added into the mix, along with Swastikas. The so-called Far Right only encourages this confusion. It makes an idol out of symbols. It is beholden to scientism, specifically racialist theory. Neither side seeks to rebuild a non-materialist civilization rooted in tradition, family, and the pursuit of virtue. The best construction I can put on them is that they have no vision of such a world.

And rarely would they get such a vision offered to them, even in the churches we all attend. Weaver identified contemporaneity as a synonym for presentism. Which of our churches hasn’t aided and abetted the assault on memory by instituting “contemporary” services, music, and art? Which of our preachers can resist the temptation to tell endless stories from the pulpit about modern life, or force ancient texts into the mold of metaphor, reducing living narratives of God’s mighty hand of salvation to facts misapplied? What is the “Goliath” in your life? Self-doubt? Prejudice? What sin against liberal democracy should we repent of this week? Such presentism steals memory from our children, robbing them even of the common language of faith. Each generation has to have multiple new translations of sacred texts, modifications to sacred songs, and words on screens instead of in books, so they are easier to alter from week to week. “Don’t let me fall into temptation.”

“To lose your language and your god surrenders all that you are,” writes Lytle in A Wake for the Living. And so we are in danger of losing more than monuments. Public (and many private) schools are teaching an entire generation to hate themselves and their history. And perhaps even worse, modern life is now enslaved to the pixelated image and unformed thought, via the internet and the ubiquitous smartphone. These devices steal from the young the very possibility of a moment of leisure, chirping and buzzing in every quiet second. “Leisure,” said Josef Pieper, is “the basis of culture.” It also is the basis of St. Paul’s prayer without ceasing. And ultimately, the uninterrupted moment is the opportunity of memory, when facts are arranged and filed on the shelves of tradition, connected by narrative. Constant animal interaction with social media and ill-named “texts” is the solvent of mind itself. This is the abolition of man with a speed and on a scale Lewis could not imagine, even for Uncle Screwtape.

Our middle-class addiction to the opioids of technology can be broken. We can renounce liberal democracy, fake history, fake news, and Marxism. But Jesus warned of casting out the demon and sweeping the house clean, without replacing him with something, or Someone, who is sacred. Seven demons will return and set up shop. In his Epilogue to The Southern Tradition at Bay, Weaver warned that the “harrowing” replacement of the liberal social order might be fascism, which might appeal to the young because it sets itself as a “protest against materialist theories of history and society.” Fascism is attractive because it values achievement, poetry, and the possibility of a dramatic life. It calls on young men to be hard on themselves, which is an appeal to basic masculine desire. This, wrote Weaver over a half-century ago, is what awaits us if we fail to learn from the Old South about the contours of a non-materialist society and the meaning of our own selves. Events here and in Europe reveal his prescience.

But I propose no grand top-down political strategy. I propose, with Weaver and Lytle and Lukacs and Russell Kirk, art, music, poetry, and sacred texts. Memory, consciousness, mind, imagination—these are the things that will bring about a return to civility, because only through them can a vision for order, rooted in Creation, occur. “Take down the fiddle from the wall,” wrote Lytle in I’ll Take My Stand. But he also told stories. And not just stories about Bedford Forrest; he told stories to and about his own family, always refining them for comedy and poignancy. Above all, we must tell our children such stories, and “remember who we are,” as Mel Bradford put it.

And so I’ll close with a story. My granny was born in a place called Paul’s Switch, Arkansas, near the town of Bono in the Delta, to poor sharecroppers, the Peeks. Her grandfather, Levi Melton, was a private in the 2nd Mississippi (Company F) Infantry, which arrived at the scene of First Manassas at noon on July 20, 1861. After heavy losses during its initial engagement with the Yankees the following day, the 2nd Mississippi reformed and joined General Jackson’s “First Brigade” in attacking the Federal batteries. They had over a hundred casualties, including 25 killed in action. Granny’s grandpa did not see action that day; he was in the hospital tent with pneumonia, which he’d contracted as it spread among the troops at Winchester, before he rode the train to Manassas. The pneumonia damaged his lungs, and he was discharged before winter. There are no statues to Levi Benton Melton; but there is memory.

Granny had a wild-eyed way about her. She deliberately mispronounced words she found foreign and funny, like the Italian dish La-GAYNE-ya. It was funny to her that we would eat such a thing, instead of boiled turnip greens, neck bones, and cornbread. She hated television. It interfered with her talking. There was always something to report on, which, in turn, reminded her of someone who was long dead or should be. Dad and Gramp and I would be watching a ballgame or a heavyweight fight, and she would walk in and talk over it. “Oh, I see you’re watching your little show,” she’d begin.

She had also learned to be suspicious of TV. She suspected the people on the other end could see you and hear you, even when the screen wasn’t turned on. This occurred to her suddenly during an early episode of Hee-Haw. Before Junior Samples gave out the number BR549, he looked directly at her and said, “I see ye there, with rollers in ye hair, in ye nightgown.” And this described her present state to a T.

“Why is that white sheet always over the TV?” I asked when I was little, on a regular basis. Each time I got the same answer. Gramp rolled his eyes. Was Granny crazy? I wondered.

The other day, we were watching a football game, and on came a commercial for something called Alexa, a product made and sold by Amazon.com, owned by Jeff Bezos, the richest man on planet earth. It’s a device plugged into the Internet that answers your questions and does things for you. It’s connected to your growing profile, stored somewhere in the aether, and it’s hooked up to your bank account. “Alexa, order pizza from Pizza Hut,” said the guy on TV to the electronic device. Steven Crowder famously asked Alexa “Who is the Lord Jesus Christ?” and the device replied, “Jesus Christ is a fictional character.” Apparently Alexa also suffers from amnesia.

“Do you realize,” I said to my children, “that in order for that thing to work, it has to be listening to you all the time? What’s it doing with all of that information?” Seized with a sudden flash of memory, I turned off the TV and, for the umpteenth time, told them the story of Granny and Junior Samples.

You can watch the talk here: