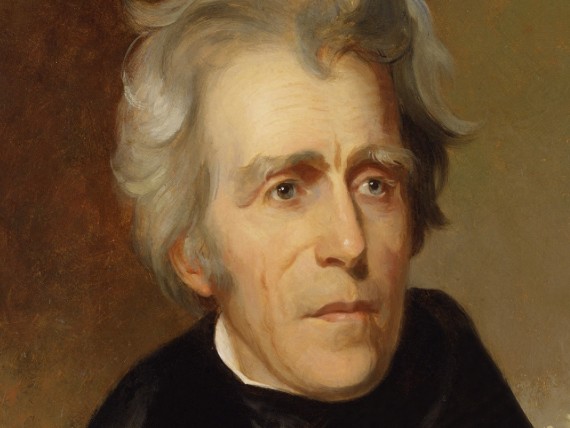

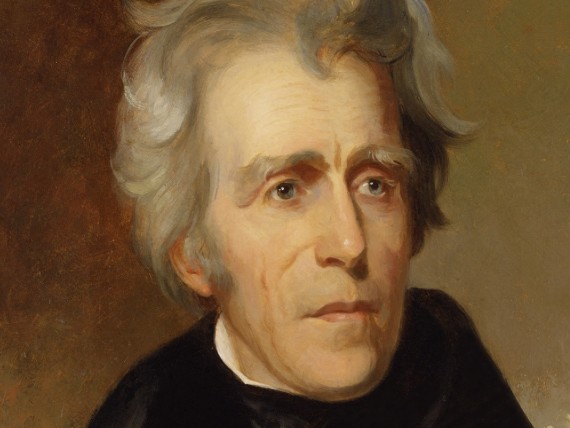

Despite nearly universal scolding in the mainstream media, President Trump’s suggestion that a compromise similar to the one Andrew Jackson arranged during the 1832 South Carolina nullification crisis might have prevented the Civil War merits analysis for four reasons.

First, those pundits accusing Trump of not realizing that Jackson was deceased before the Civil War began either did not understand that he was suggesting that methods similar to those Jackson used to end the 1832 South Carolina Nullification Crisis might have also aborted the 1860-61 Secession Crisis, or they simply lied.

In 1832 South Carolina declared that the high tariffs of that year and 1828 were unconstitutional and would therefore be unenforceable in their state after the end of January 1833. In response, President Jackson obtained congressional authority to militarily force South Carolina to comply. He also persuaded Congress to adopt a more moderate tariff. When South Carolinians realized that Jackson would not let them defy federal authority they accepted the new tariff as a compromise. War was averted.

About three years earlier, in April 1830, prominent leaders gathered in Washington to celebrate the birthday of Thomas Jefferson who had died in 1826. Vice President John C. Calhoun of South Carolina hoped, by means of a toast, to use the occasion to identify Jefferson as the father of the Nullification principle that the Palmetto State would later use in its attempt to void the 1828 and 1832 tariffs. As president, however, Jackson was asked to make the first toast. Since he was aware of Calhoun’s intent and objected to it, the president’s salute to the author of the Declaration of Independence was a simple, “The Federal Union: It must be preserved!”

Second, the reasons for Southern secession in 1860-61 and the reasons for the ensuing war were different from one another. The Northern states, after all, could have let the Southern states leave in peace as many prominent abolitionists advocated before the fighting began. Examples include Horace Greely, William Lloyd Garrison, Henry Beecher, Samuel Howe, John Greenleaf Whittier, James Clark, Gerrit Smith, Joshua Giddings, and Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner who would later become a leading war hawk. Garrison’s decades-long hunger for separation is underscored by his statement that the constitutional Union was “a covenant with death and agreement with hell.”

Although the best of the media-selected Trump critics itemized reasons for Southern secession, none explained why Northerners declined to let the South leave peaceably. Even the Pulitzer Prize winning dean of modern Civil War historians, Eric Foner, admits that he cannot explain it. For example, in this lecture he asks, “Why not just let [the Southern states] go? Good question! You can adduce answers [such as] The American Mission, Unionism, Nationalism. Very few people in the North said, ‘Let them go.’ Why? [To answer that] requires us to do what no historian has ever successfully done.”

Foner’s inability to explain why the North decided to fight reflects a gigantic blind spot caused by his anti-Southern historical interpretations. The real reason the North chose war was to avoid the economic consequences of Southern secession. Consider the following points:

1. Southern cotton alone accounted for about two-thirds of all American exports and all Southern exports represented about four-fifths of the country’s total. A truncated federal union composed solely of Northern states could not hope to maintain a favorable international balance of payments. The situation would be worse if the Northern states tried to match the anticipated low tariffs in the new Confederacy. Ten days before South Carolina led the cotton states into secession on December 20, 1860, the Chicago Daily Times editorialized on the calamities of disunion:

In one single blow our foreign commerce must be reduced to less than one-half what it now is. Our coastwise trade would pass into other hands. One-half of our shipping would be idle…We should lose our trade with the South, with all its immense profits. Our manufactories would be in utter ruins…If [our protective tariff] be wholly withdrawn from our labor…it could not compete with the labor of Europe. We should be driven from the market and millions of our people would be compelled to go out of employment.

2. If the Confederacy were to survive as a separate country its import tariffs would likely have been much lower than those of the federal union. President Jefferson Davis announced in his inaugural address, “Our policy is peace, and the freest trade our necessities will permit. It is…[in] our interest, [and those of our trading partners] that there should be the fewest practicable restrictions upon interchange of commodities.”

3. Low Confederate tariffs would confront the remaining states of the abridged Union with two consequences. First, since the federal tax base relied chiefly upon the tariff the government would lose the great majority of its tax revenue. Articles imported into the Confederacy from Europe would divert tariff revenue from the North to the South. Additionally, the Confederacy’s low duties would encourage Northern merchants to import European goods by smuggling them across the Ohio River, or the Northwestern states might secede themselves to form a third country in order to unilaterally set low import duties from the Southern Confederacy. Second, a low Confederate tariff would make Southerners more likely to buy manufactured goods from Europe as opposed to the Northern states where prices were inflated by protective tariffs.

The third factor that the media critics of Trump’s remarks about Jackson fail to understand is that Northerners did not go to war to abolish slavery. The Party’s slavery plank in the 1860 election that made Abraham Lincoln president was merely to prohibit the expansion of slavery into the federal territories that had not yet been admitted as states. Such territories were chiefly in the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountain region east of the Pacific Coast states.

In his March 1861 inaugural address President Lincoln expressly stated, “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” Regarding a constitutional amendment that would forever block the federal government from interfering with slavery in the Southern states then being considered by Congress he added, “…I have no objection to its being made express and irrevocable.”

Finally, even those commentators that admitted Trump was alluding to Jackson’s role in the 1832 Nullification crisis failed to realize that secession-crisis lame duck President James Buchanan actually did try to emulate Jackson’s methods to avert civil war. He was unsuccessful because the Republican Party would not compromise. Republicans insisted that there would be no exceptions to their campaign plank to keep slavery out of all federal territories.

They even rejected a proposal to permit slaves to be taken into only those western territories south the latitude applicable to Missouri’s southern border, which probably would have ended the crisis. Since the natural features of the pertinent region—later the states of Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma—were intrinsically inhospitable to slavery the chances that they would enable the institution to spread outside the South were about as remote as a Cherokee Indian getting elected Pope.

Even though such a compromise would not have ended slavery in the South, it bears repeating that Lincoln conceded he did not go to war intending to interfere “with the institution of slavery in the States where it exist[ed].” Furthermore, he later admitted shortly before issuing his Emancipation Proclamation that he “view[ed] the matter as a practical war measure, to be decided upon according to the advantages or disadvantages it may offer to the suppression of the [Confederate] rebellion.”

In short, it was Union military reversals during the summer of 1862 that led Lincoln to adopt the Emancipation Proclamation. He confided to Navy Secretary Gideon Welles that emancipation was “a military necessity, absolutely essential to the preservation of the Union. We must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued.” In the same context Jefferson Davis told Union peace commissioners in July 1864, nine months before the war ended, “we are not fighting for slavery. We are fighting for independence.” Moreover, after Congress finally gave him a bill in March 1865 to incorporate blacks into the Rebel armies, President Davis basically granted them freedom. Specifically, by executive order he stipulated that blacks admitted into the Rebel armies must be volunteers, accompanied by manumission papers.

Editor’s Note: On May 19, 2017 Westholme Publishing will release Phil’s fifth Civil War era book titled, Southern Reconstruction.