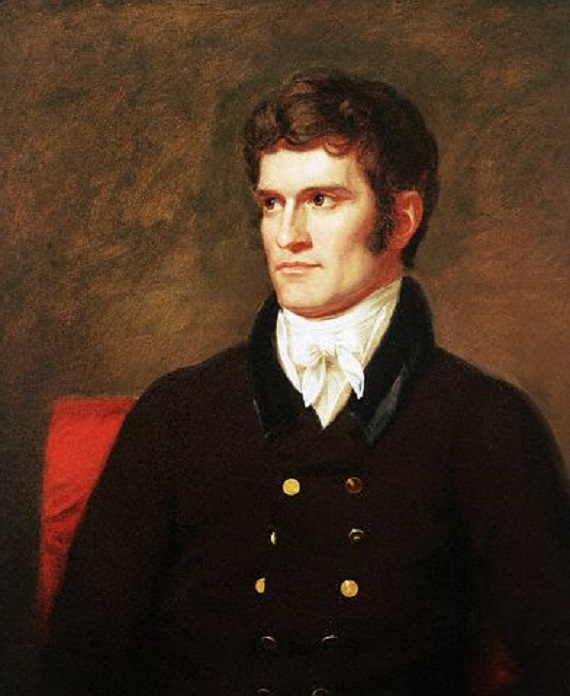

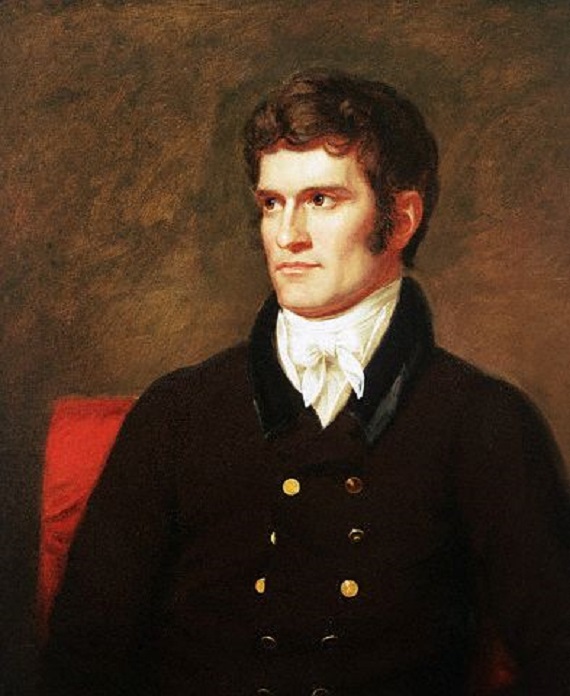

Much of John C. Calhoun’s criticism stems from his 1837 speech in the Senate where he stated slavery was “a positive good.” This quote is often paraded as evidence of Southern racism and is used in attempts diminish Calhoun’s legacy. Quite possibly no other politician, aside from Lincoln, is so often misrepresented and misunderstood.

The reason is that nowadays, we live in a world without genuine political philosophers. If you want to know just how distorted our collective American memory is, google “American political philosophers,” and you will come upon a Wikipedia page listing men like Harry Jaffa, Leo Strauss, and Henry David Thoreau. Not surprisingly, Calhoun is conspicuously absent even though his “Concurrent Majority” could probably solve a lot of the deep divisions across the country right now.

Most people with common sense know that Calhoun was not speaking about the idea of slavery when he said it was a positive good; he was speaking of how he saw slavery practiced in the South. He saw a constantly growing slave population, living in conditions where “so much is left to the share of the laborer, and so little extracted from him…where there is more kind attention paid to him in sickness or infirmities of age.” Unlike “free” blacks in the North, black slaves in the South had the right to be taken care of from birth until death.

While Southerners were living alongside an ever-expanding black population, several Western and Midwestern states had laws written into their state constitutions that did not allow black people to move there or outright excluded them. Ohio enacted Black Laws in 1804 and 1807 that required blacks entering the state to post a bond of $500 guaranteeing good behavior and provide court documentation of their freedom. When Virginian John Randolph’s 518 slaves were emancipated following his death, an Ohio congressman warned: “the banks of the Ohio … would be lined with men with muskets on their shoulders to keep off the emancipated slaves.” Even as far West as Oregon, blacks were not allowed to hold real estate, make contracts, or bring lawsuits.

Lincoln’s home state of Illinois was particularly cruel. Even before it became a state, it was restricting the freedoms of black Americans. In 1813, the Illinois Territory forbid the entry of free blacks. Its laws also threatened that any black residents who entered, and did not leave within 15 days, could receive 39 lashes.

When looking at the legal status of blacks up to 1860, no Northern state allowed black male jury duty and the states of Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin forbid black male suffrage. New York, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio had laws that restricted the black vote at various times. For example, in New York, a $250 property requirement kept most black New Yorkers from voting. In 1855, only 100 out of 11,000 blacks in New York City were allowed to vote.

Even though some Northern states ended slavery early on, blacks still faced much hardship there. One account of this fact can be seen from Charles Mackay, an English visitor to America from 1857-1858, in his work Life and Liberty in America. He had the following to say about racism in the North:

“This is the prevalent feeling, if not the language of the free North… ‘We shall not make the black man a slave; we shall not buy him or sell him; but we shall not associate with him. He shall be free to live, and to thrive, if he can, and to pay taxes and perform duties; but he shall not be free to dine and drink at our board [table] – to share with us the deliberations of the jury box – to attend to us in our courts – to represent us in the legislature – to attend to us at the bed of sickness and pain – to mingle with us in the concert-room, the lecture-room, the theatre, or the church, or to marry with our daughters. We are of another race, and he is inferior. Let him know his place – and keep it.”

Another source showing how discriminatory the North was can be found in Charles Andrews’ The History of the New York Free-Schools, from 1830. The book features a graduation speech by a young black man, the first in his class at a New York City free school, in 1819:

“…Why should I strive hard and acquire all the constituents of a man if the prevailing genius of the land admit me not as such, or but in an inferior degree! Pardon me if I feel insignificant and weak…Where are my prospects? To what shall I turn my hand? Shall I be a merchant? No one will have me in his office; white clerks won’t associate with me. Drudgery and servitude, then, are my prospective portion. Can you be surprised at my discouragement?”

Because the North is the real hotbed of American bigotry, Calhoun and his ilk had to be portrayed as the disunionists and racists. If people looked at history as it was, and not how they believe it to be, the whole paradigm of centralization, along with the idea of the War Between the States having been a moral drama, would fall apart.

Calhoun clearly explained his meaning of slavery being a “positive good” when he said: “Compare [the slave’s] condition with the condition of the tenants of the poor houses in the more civilized portions of Europe – look at the sick, and the old and infirm slave, on one hand, in the midst of his family and friends, under the kind superintending care of his master and mistress, and compare it with the forlorn and wretched condition of the pauper in the poor house.”

Other historians, and even Northerners, have made similar statements. A Northerner writer named Solon Robinson, who worked for Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, published a book titled Negro Slavery in the South in 1849. In this work, he copied Calhoun verbatim on slavery and stated the following about blacks in the South: “As a race of people, they are far more comfortable and happy, and enjoy a condition far more enviable, than that of nine-tenths of the laboring peasants of Europe…”

On the question of what slavery is, Robinson wrote the following:

“And here let me inquire, what is slavery—you understand it? Is it to be better fed, better clothed, better housed, better lodged, better provided and cared for in infancy, sickness and old age, better loved and respected by master, mistress, children and fellow laborers, better instructed in the principles of morality and religion, and, finally, at the close of a long life of light labor, comfort and happiness, to be better and more decently buried, than are millions of the laboring population of FREEMEN in Europe, and thousands of the same class in this boasted land of liberty? For this is most truly the condition of slaves in the South.”

It’s disturbing to think that Calhoun is considered one of the foremost racists for saying these things, when various Northerners and modern economists have echoed his logic.

Take sweatshops for example; most people will agree that in today’s world, it is unacceptable for people to be working in sweatshop conditions for little pay. Yet the social justice warriors do not speak out about it, and instead are buying shoes, clothes, and endless amounts of accessories that are made in places like Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia under those very conditions.

Just in 2016, the U.S. National Bureau of Economics Research did a study in Ethiopia that showed sweatshop labor is dangerous, undesirable, and pays less than self-employment in the informal sector. An article even claimed that the study shows sweatshops may be a “necessary evil.” The New York Times published an article on April 27, 2017 titled Everything We Knew About Sweatshops Was Wrong. The article quotes economist Joan Robinson, who stated: “The misery of being exploited by capitalists is nothing compared to the misery of not being exploited at all.” Even The Adam Smith Institute has an article titled Sweatshops Make Poor People Better Off, which states “Sweatshops are awful places to work. But they are often less awful than other jobs sweatshop workers could take.”

Calhoun understood these problems, which is why he stated “there never has yet existed a wealthy and civilized society in which one portion of the community did not, in point of fact, live on the labor of the other.” He knew that the conflict between labor and capital was as old as civilization itself, but believed the South would prosper if it could have governed itself without agitation.

To the discerning eye, something is not right here. Because Calhoun made these arguments regarding slavery and free labor, his legacy has been mired with controversy. But when Northerners and all the fancy economists find new ways to repackage his arguments, they come off as academics and have to assume no responsibility. In essence, the gatekeepers of acceptable thought have taught us that it is okay to exploit laborers in other countries because it is a “necessary evil” – but when Calhoun talked about these problems in America, he was a racist trying to break up the Union. Does anyone see the irony?