Black slaves toiling in the fields of large plantations, gentlemen in frock coats and ladies in hoop skirts relaxing on the verandas of large mansions . . . all set in places named Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland and Mississippi. Most would imagine this to be a picture of the antebellum American South, but they would be mistaken, as it would actually be a scene from mid-Nineteenth Century Africa. More specifically, an area on the Ivory Coast that contained not only Liberia, but the colonies of several Southern states.

To set the stage for our African story, we must first return to America’s earliest days. Contrary to what is claimed by the “1619 Project,” the first group of black Africans brought to the British Colony of Virginia that year did not become slaves there, but were employed as indentured servants who, like their white counterparts, had the opportunity of gaining their freedom by working off their indentures. Most of those early African arrivals became the first free blacks in America.

Even though actual chattel bondage had begun in America by the mid-Seventeenth Century, up until 1700 only about twenty thousand Africans had been brought to the North American colonies as slaves and, therefore, the number of free blacks also remained small. During the next century, however, almost three hundred thousand slaves were transported to the United States and this, combined with an extremely high black birth rate, created approximately four million black slaves in America by 1860, along with more than half a million free blacks. Of the latter number, well over half resided in the South.

By the start of the Nineteenth Century, prejudice against blacks had already developed throughout the country but such bias in the South differed greatly from that in the North where, unlike the South, it was generally felt that blacks and whites should not coexist. One answer to the problem was to return free blacks to Africa, and in 1816, a group for that purpose was founded.

The concept of African colonization for America’s free blacks was conceived five years earlier by a Quaker ship builder from Boston, Paul Cuffee, whose father was a former Massachusetts slave from West Africa and his mother a member of the Wampanoag Tribe on Cape Cod. During a voyage from Philadelphia to the African West Coast in 1811, the idea came to Cuffee that former slaves might be better off by returning to Africa. Upon his return to America, he recruited thirty-eight free blacks as colonists and in 1815, took them to the British Colony of Sierra Leone on Africa’s West Coast that had been establish in 1787 as a home for England’s free blacks.

News of this event inspired such prominent Americans as Congressmen Henry Clay of Kentucky and Daniel Webster of New Hampshire, attorney Francis Scott Key of Maryland and three Virginians, Treasury Secretary William Crawford, Senator John Randolph and Supreme Court Justice Bushrod Washington, to form an organization for promoting colonization in Africa. In December of 1816, the group, headed by Presbyterian clergyman Robert Finley of New Jersey and with the support of President James Monroe, met at the Davis Hotel in Washington and formed the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, later shortened to the American Colonization Society. Up until the 1860s, many other American political leaders, including Abraham Lincoln, were strong supporters of the Society’s aims. After his election, however, Lincoln advocated such colonization in the area of Central America that is now Panama.

Chapters of the new Society were soon created throughout both the North and South and in 1821, agents for the Society headed by Navy Lieutenant Robert Stockton sailed from New York to the African West Coast to seek land for a colony. That December, they arrived at Cape Mesurado on the Pepper Coast near the British colony of Sierra Leone and began land acquisition negotiations with the local ruler, Zolu Duma, also known as King Peter. After some coercion, King Peter finally agreed to sell a thirty-six mile long strip of coastal land to the Society and the following year, the colony of Liberia was established with Monrovia as its capital.

A number of the Society’s state chapters followed suit during the next fifteen years and started their own settlements which greatly expanded the area. These state colonies included New Georgia in 1826, Kentucky-in-Africa in 1828, Mississippi-in-Africa in 1831, the Republic of Maryland in 1834 and a Pennsylvania colony known as Bassa Cove in 1835. Society members in New Jersey had also planned a colony, but it was never established.

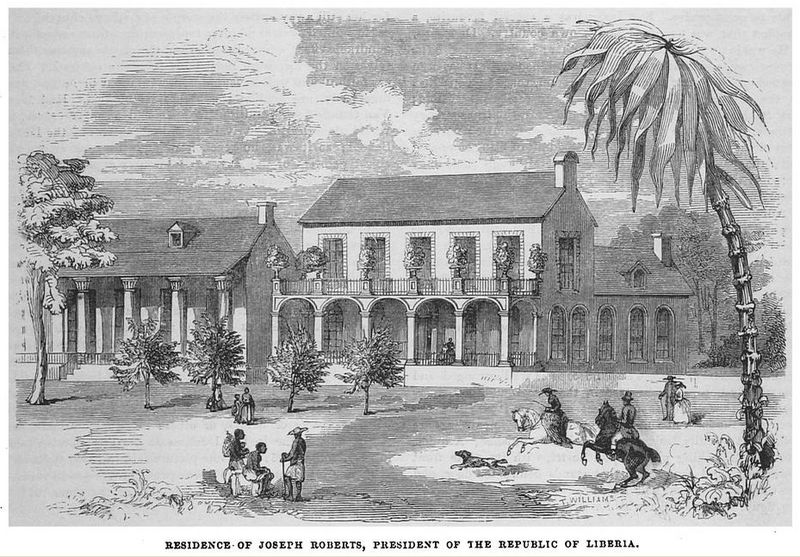

By 1837, Liberia had united all the separate state colonies and two years later, under the guidance of the Society, formed the Commonwealth of Liberia with a former free black from Virginia, Joseph Jenkins Roberts, as its governor. In 1847, Liberia declared its full independence, formed a constitutional republic and elected Roberts as its first president.

Roberts had been born free in Norfolk in 1809 and at age twenty, migrated to Liberia where he became a merchant in Monrovia and served as sheriff there in 1833. After taking office as Liberia’s first president in January of 1848, Roberts traveled to Europe seeking recognition for the new republic, meeting first with Queen Victoria in London. Great Britain granted Liberia recognition that year and from 1852 to 1867, so did France, some of the German states, Belgium, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Portugal and Austria. The United States, however, did not establish formal diplomatic relations with Liberia until 1862 and the world’s only other black republic at that time, Haiti, not until 1864.

From Liberia’s birth in 1821 until the beginning of the War Between the States forty years later, some twelve thousand free blacks from various parts of America had settled in Liberia, with the majority coming from the South. The early settlers, known then as Americo-Liberians, ruled the area for well over a century, with those from the South, many of whom were former slaves, bringing with them all that they had known in the South and replanted it firmly in the soil of Africa. They adopted a Southern mode of life, including homes and buildings that resembled those in the South and all manner of Southern dress and customs, as well as plantations worked by native slaves.

One of the largest and most influential of the Southern groups was located in and around Harper, the capital of the former Republic of Maryland that existed from 1834 until 1837. Even today, parts of the town of Harper, the capital of what is now Liberia’s Maryland County, still contain remnants of the antebellum South. An example would be the ruins of a Southern-style mansion that was once the home of William Vacanarat Shadrach Tubman, the president of Liberia from 1944 to 1971.

Tubman’s grandparents, William and Sylvia, were two of the sixty-nine slaves that had been freed in 1837 by their owner, Emily Tubman of Augusta, Georgia. Mrs. Tubman was a friend of Henry Clay who had suggested she send her freed slaves to Liberia and they arrived there in 1844. Rather than establishing a new land of liberty though, the former Tubman slaves, like others that had been freed and sent to Liberia before them, emulated their former white masters and created a mirror image of the antebellum South.

The same occurred with many of the new settlers from the United States, with the men and women dressing themselves in tailcoats and hoop skirts and setting out to recreate a microcosm of the world they had known in America. Those who could afford to do so built large Greek-revival mansions and laid out extensive plantations. The Americo-Liberians also became the absolute rulers of their new land and not only denied the indigenous natives many political rights, such as the right to vote, but used them as virtual slaves on their plantations.

For almost four decades after President Roberts took office in 1848, all of the eight men who followed him as president had come from America with all but one, Edward Roye of Ohio, having been born in the South. Even Liberia’s first native-born president, Joseph Johnson, as well as all the others until 1980, had come from families of free-born or former slave immigrants. The last of the Americo-Liberian line of presidents was William Tolbert whose grandparents had been slaves in South Carolina and Virginia. Tolbert had succeeded President Tubman in 1971 but was executed in 1980 during a violent military coup d’état led by army sergeant Samuel Doe who abolished the nation’s constitution and declared himself president. Thus, after over a hundred thirty years, Doe became Liberia’s first chief of state from a local native tribe.

Some might then ask, if both slavery and the the antebellum South in which the institution existed are now condemned as evil, why would those who had actually experienced such evils want to recreate them in the land of their ancestors. Many today would merely dismiss it with some Kafaesque psychobabble about a form of social metamorphosis in which the victim assumes the role of oppressor, but this would not be the case. The truth is that those who knew slavery first hand and whose roots were in the South viewed such things in a far different light than those who, for their own ends, now wish to condemn the South for what they perceive as its crime against humanity.

This was all brought to light over eighty years ago when, from 1936 to 1938, historians of the Federal Writers Project in President Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration interviewed two per cent of the more than a hundred twenty thousand former slaves still living at that time. While the responses were varied, ranging from fond memories of better times during their life of servitude to bitter accounts of cruel punishment, over eighty per cent of the respondents expressed generally favorable opinions of their former lives and masters.

As far as the remembered better times, the interviews clearly revealed that in many cases the former slaves did have a far better standard of living in bondage than after emancipation when it came to such basic needs as food, shelter, clothing and medical care. Other studies also showed that many workers in the North during the antebellum period, particularly newly arrived immigrants, fared far worse in regard to such needs, and certainly in the matter of job security.

The accounts of punishment should also be viewed in their proper context. Such punishment invariably referred to flogging, but corporal punishment was then standard practice in America for many crimes and remained so until well into the next century. At that time, flogging was also normal punishment in the U. S. military, as well as in schools and the home.

If one were to select a single interview to best illustrate the matter, perhaps the one with eighty-eight year old Elizabeth Finley of Gulfport, Mississippi, would serve the purpose. In her narrative, Ms. Finley spoke of her extremely hard life after the War and compared it to the life she had led in Gulfport where she had been born a slave in 1847. In her story, she said that “her white folks” were rich, lived in a “big white house with round posts in front” and that while they gave their slaves “plenty to eat and wear,” they also “beat on them plenty.”

Further on, she stated that “them Yankee men” told the slaves that “the government would give us some land and a mule to work with, but we never did get anything from them.” She ended by saying that they were “mighty proud of their freedom, but life is harder now than is was in those (earlier) times.” Many of the slave narratives repeated the same story of how hard their current lives were in comparison with the abundance they had known in bondage.

What took place during the formation of Liberia two centuries ago certainly does not coincide with today’s skewed concept of slavery and the antebellum South. Also, present-day media accounts of Liberia’s unusual early history are designed more to shock than to inform, but considering the background of those who created the nation, the actual history should not be surprising.

Of the seven Southern presidents who founded and first led Liberia, all but the final chief executive, former Kentucky slave Alfred Russell, had been born free. The Southern way of life they knew, therefore, was what they brought with them to Africa and transplanted there. Furthermore, it should also seem perfectly normal, judging from many of the comments made by actual former slaves, that those who settled in Africa would feel right at home in the Southern setting that had been created for them.

As always, fascinating and informative. I previously didn’t know of Sierra Leone’s history, nor so much detail about Liberia.

It is impossible to stay ahead of the lies. Your enemy is not one with a moral code. Lies are just a tool of their trade.

Let’s start at the beginning.

No one was ever enslaved in the English colonies (WE know this is not true, as you will see in Casor vs Johnson). All were enslaved in Africa, first. What were the names of those large sailing vessels coming to the New World from Africa? They were all named “slave ships” after the practice of settling trade imbalances with African chieftains was made popular by the first banker who realized cheap labor could fill empty cargo holds coming from Africa to the New World.

Who owned the ships? Was it even possible to own a ship without the blessing of the powers that be at the time? You do understand the King’s Forest was sacred because it held protected wood to build these ships? Lose your life for cutting down one of the King’s trees, lad. And of course, you didn’t just sail the high seas without the protection of the Royal Navy…and that protection came at a price. EVERY HEAD WAS TAXED IN TRANSIT…THE ROYALS GOT A CUT FROM EVERY SLAVE MOVED ACROSS THE ATLANTIC.

In the book PRINCE AMONG SLAVES, one is able to read from a first-hand account the “horrors” of slavery. There are very few. If there were more written accounts of life as a slave in Africa, we could have more to compare, but alas, there wasn’t much written language in Africa at the time. Read PRINCE AMONG SLAVES…and start to peel back the onion.

We all know the sham that is the 1619 Project…it is hardly worth mentioning except for its recent appearance on the stage of lies. If the first slave in the colonies was John Casor, who was awarded to Anthony Johnson in 1655 according to the NAACP website, how could slaves have been brought to the colonies in 1619? Anthony Johnson, a free black…as all blacks were free then unless they were indentured…was the first owner of a black slave in the English colonies.

We can delve into why blacks were ever even brought to the colonies since there were literally millions of whites eligible for indentured service in Europe. Malarial resistance is the only reason, as the malarial zone in the colonies that would become the united States started at the Mason-Dixon line and proceeded Southward. Of course, African chieftains desired to trade with Europeans for all the products unavailable in Africa, such as anything not consisting of their enslaved populations. As can be seen in PRINCE AMONG SLAVES, this relationship among Africans was tenuous at best as the line between owner and owned was drawn between the winners and losers of the previous night’s raid.

How were these slaves bought and paid for? Did the Captain of the ship make these deals? Did he carry gold in his hold to purchase the slaves whose lives were forever altered by gaining life in the New World as opposed to life in Africa? No, the Captain carried letters of credit. Letters of credit issued by the Royals or by the banks controlled by the Royals for the benefit of the Royals or perhaps by that group of people who would create modern banks. Letters of Credit. Not gold. Gold was kept in vaults in London and Madrid and Lisbon but not in the holds of ships. Start on another layer of the onion.

There are many lies about how gentle slavery was in Africa, since after all, some black scholars realized the comparison would eventually be made…so this lie evolved about how “humane” life was as a slave in Africa. If there were any written documents describing this wonderful existence, we could know if those who lie continuously have strayed from their modus operandi…alas, there was very little writing of any kind in Africa at this time.

The Corwin Amendment. Juneteenth. MLK, the cheerleader for a rapist. Jesse Jackson, who lied about holding dying Martin in his arms.

Lies without cease. The biggest lie…SLAVERY WAS HORRIBLE…see BT Washington’s UP FROM SLAVERY…just read the first chapter…it is available for free at the LOC…the LOC, perpetuating the Lost Cause myth by presenting the lies in UP FROM SLAVERY.

Final question for the reader…HOW IS IT THAT THERE WERE MORE FREE BLACKS IN THE CONFEDERATE STATES THAN IN THE REMAINDER OF THE UNION?

First, to migrate north, you must be allowed to move into northern States. In 1857, Illinois, Land of Lincoln passed an Amendment to their State Constitution denying blacks the right to migrate to their “country”…Illinois was not alone in these restrictions. Perhaps you have heard of Oregon?

Secondly, no one was freeing northern slaves…the slaves were mainly in the South, in the malarial zone where they held an advantage over European labor due to their resistance to malaria. But ask yourself, Who would free a valuable slave, depriving heirs of valuable property? By and large, White Christians freed this valuable property though we all realize slaves were owned by the Five Civilized Tribes, free blacks, Mary Todd Lincoln, US Grant…

Enough for now…

Peel back the onion.