In the long range of history the war correspondent, a journalist embedded with a fighting army, is a fairly recent development. George Kendall was the pioneer. He was with Winfield Scott’s army during the U.S/Mexico War 1846—1848, from Vera Cruz to Mexico City. Like the soldiers he faced sickness and was wounded.

His 215 dispatches from Mexico were the primary source of news of their distant army for nearly all Americans. The dispatches went by horse relay from the interior to the Mexican coast and by water to New Orleans. There they were printed in the Picayune and then went by water to the east coast cities and by horse to the existing telegraph lines. (The telegraph did not reach New Orleans until July 1848.)

In a short time after Kendall’s exploits the war correspondent calling began to flourish, a result of the new phenomenon of mass circulation newspapers. Several British newspapermen made notable careers reporting on the Crimean War in the 1850s, then on the American fighting in the 1860s and on various British colonial expeditions. In the 20th century the War Correspondent became a familiar figure, and some of them became famous.

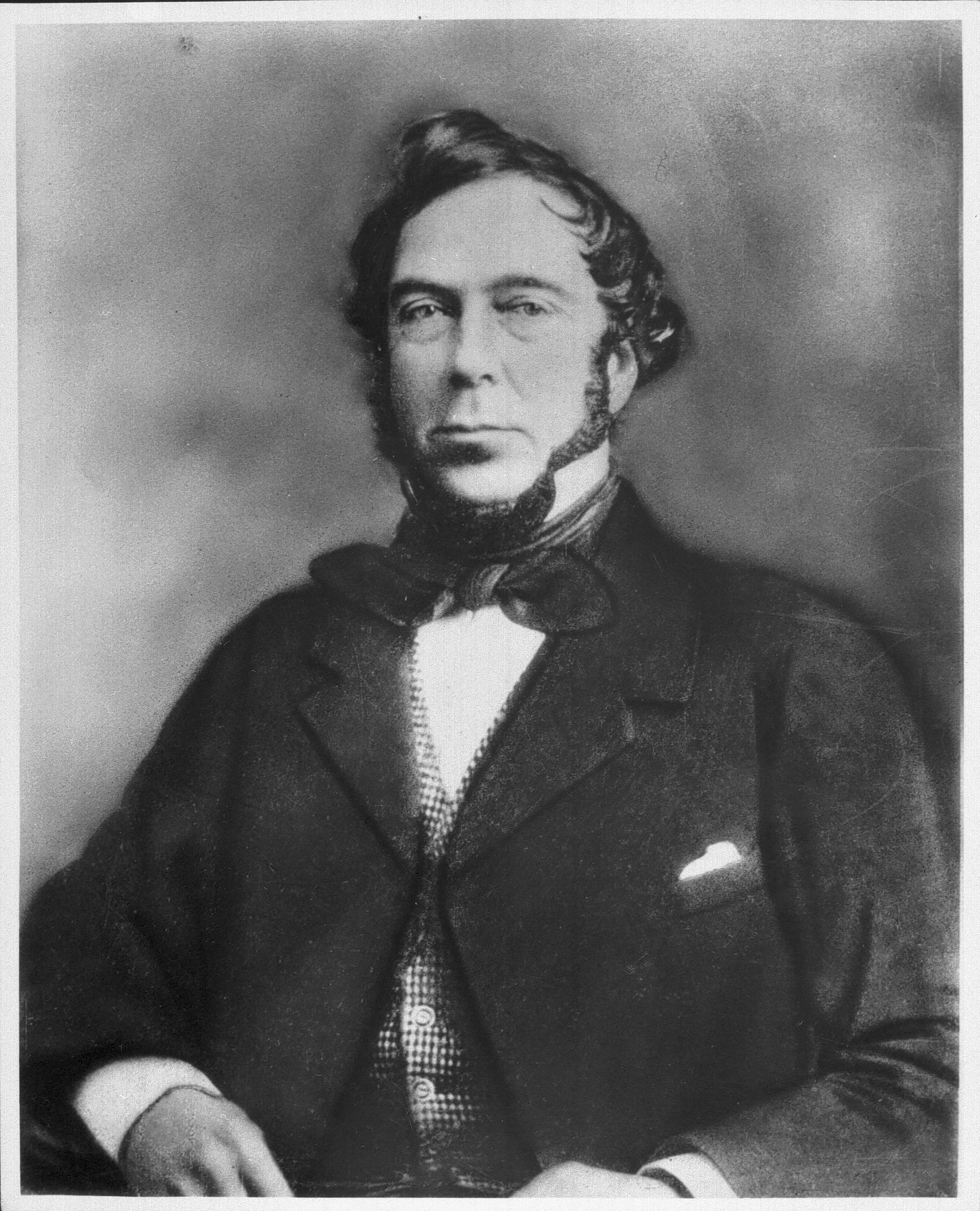

George Wilkins Kendall was born in New Hampshire in 1809. He lived in various places and at the age of 14 he knew the printing business well and was soon working in New York. At maturity, like many intelligent and adventurous Northerners, he headed South, first to Mobile and then to New Orleans.

In 1837 Kendall co-founded the New Orleans Picayune, a paper that has had a long and significant history. The paper sold for a picayune, a Spanish 6-½ cent coin common in New Orleans. Kendall was enterprising, soon extending regular coverage to the newly independent Texas Republic where travel and communication were not easy to say the least.

He also became Southerner enough to, like his neighbours, refer to people from his native New England that he encountered as examples of the peculiar untrustworthy race of Yankees.

The hardships suffered in the Mexican War were nothing compared to Kendall’s ordeal earlier, accompanying the ill-starred expedition of Texans to Santa Fe, 1841-1842.

Texas was an independent republic and it laid claim to lands above the Rio Grande. President Mirabeau Lamar wanted to establish some jurisdiction over New Mexico. He sent official emissaries. There was reason to believe they would be well-received since many Americans and Europeans already lived in Santa Fe and the Mexicans there were thought to lack any serious attachment to the corrupt, tyrannical government of Santa Anna far-away in Mexico City.

There was an established trade route from St. Louis to Santa Fe. But this was a Texas expedition and intended to go from Austin. That meant crossing West Texas and New Mexico territory that was largely unknown and unmapped, full of several varieties of dangerous terrain, with a scarcity of water and forage, and roamed by the Comanche and Apache, the most murderously effective of American tribes.

The expedition that left Austin for Santa Fe consisted of Texas officials, about 320 volunteers, mostly experienced frontiersmen, a wagon train of merchants with goods worth $200,000, and much of its food still on the hoof. Mexicans, if they chose, could regard it as an invasion. Kendall was a U.S. and not a Texan citizen and he joined in mainly from a desire to see Mexico. As it turned out he endured all the ordeals that faced the Texans.

Kendall’s experience was told in a remarkable book, Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe’ Expedition, which was read in Europe as well as America.

The book is an almost day-by-day account of the ordeal of the year- long event. It also contains a lot of interesting information about geography, weather, and creatures like horses, mules, and cattle that were part of the intimate daily experience of people of the time. His description of a buffalo hunt and prairie dog communities must have been among the first published. His observations on the character of Mexicans and frontier Southerners are priceless.

Throughout his ordeal, which was to include smallpox and imprisonment in a leper hospital, Kendall maintained a lively attitude as one who made the best of any situation and retained, usually, his sense of humour and his skill of alert observation and judgment. He seems a remarkable man.

The expedition left in June 1841 and reached New Mexico territory in September. The expedition had already from necessity split into various separate parties. The main party was accosted by a Mexican force of 1500. They agreed to surrender upon a promise of safe conduct out of Mexican territory, and in the guise of peaceful official representatives accepted being disarmed, a fatal mistake since Texans, even when badly outnumbered usually won in battle. The next day a large Mexican army appeared, put the Texans in chains and started them on a grueling 2,000- mile march to Mexico City where they were supposedly to face trial.

The prisoners’ ordeal of hunger, thirst, sickness, decayed clothing, and brutality caught world-wide attention, but was of no immediate help to them. Sometimes they were murdered in cold blood or chosen by lot for execution. The sick were left, usually unattended.

The survivors who were freed at Vera Cruz in June 1842 numbered 47, including Kendall, although many had escaped in various ways before that.

Kendall’s portrayal of Mexicans seems remarkably fair considering his situation. The plain people were generally kind and fair, often helping the suffering prisoners, as did some priests. They lived with poverty, tyranny, and abuse. Some of their customs were attractive, others not so much.

The officials were another matter. They were a strange mixture of men who aspired to be honourable and others who were cruel brutes. In either case, in the eyes of the Texans, they were pompous and duplicitous. A reader can begin to understand hostility between Texans and Mexicans, even those who were generally people of good will.

Given his New England background, Kendall was familiar with the wool industry. He became the leader in bringing sheep raising to Texas. He passed away in 1867 at his sheep ranch in the Texas county that is named for him.

You can download and read Narrative of the Texan Santa Fe’ Expedition, at https://archive.org/details/narrativeoftexan11kend/page/n7/mode/2up

I was born in New Orleans and was raised approximately 13 miles outside of Bourbon Street in a nearby town called Violet. I grew up in the same Parish as PGT Beauregard but I never knew this history. Thanks, Prof. Wilson for the history lesson.