After the War Between the States began, President Abraham Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus, and during the course of the conflict, thousands of citizens (mostly Northerners) were arrested and incarcerated in various prisons without due process. Thomas DiLorenzo, author of Lincoln Unmasked, wrote that “virtually anyone who opposed [the Lincoln] administration policies in any way was threatened with imprisonment without due process. This included elected officials, newspaper editors, and thousands of ordinary citizens of the Northern states. Lincoln himself argued that those who simply remained silent and did not publicly support his administration should also be subject to imprisonment.”

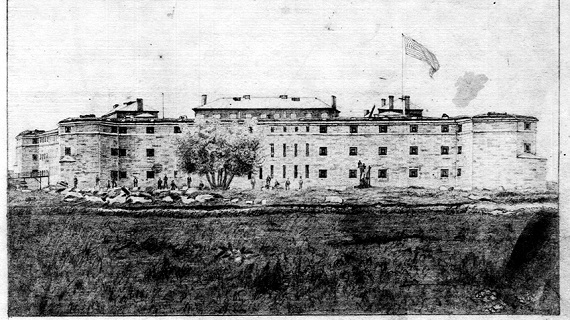

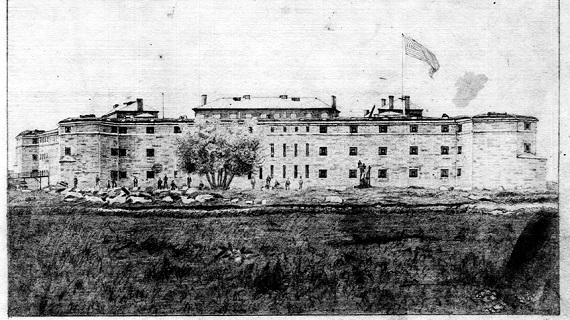

One of these political prisoners was Reverend Isaac William Ker Handy (1815-1878), a civilian clergyman incarcerated at Fort Delaware. Rev. Handy pastored a church in Portsmouth, Virginia, an area which had been captured by Union forces in 1862. In June of 1863, the clergyman was issued a special pass by the Federal officer in command at Portsmouth to go behind Union lines to visit family and friends in the state of Delaware. There, a supposed friend reported something Handy had said in a private conversation that was critical of the United States government, and the clergyman was soon arrested, and without trial or due process, imprisoned at Fort Delaware.

Handy was a middle-aged man close to fifty years old, and his health suffered during his confinement, but during his fifteen months at Fort Delaware he kept a diary, and after the war, it was published, and now serves as one of the most useful and reliable sources of information on the conditions at the prison from July 1863 to October 1864. The diary, over 600 pages long, is an almost daily recounting of incidents and conditions at Fort Delaware. During his imprisonment, the clergyman kept his writings carefully hidden, and many were smuggled out of the prison in increments and preserved by his wife, who was allowed to visit him.

Rev. Handy believed that taking the oath of allegiance to the United States was tantamount to giving approval to the war. He called himself “a prisoner for conscience’ sake,” and refused to yield, although by taking the oath, he could have secured his release. His diary mentions at least two political prisoners who took the oath and were allowed their freedom.

He often marveled at the ferocity with which the North conducted its war against the Confederacy, and Northerners’ extreme “bitterness toward the South,” noting that “the extermination of the [southern] race is not, with them, a mere matter of talk.” He was especially dismayed by the vicious sentiments that emanated from Northern pulpits and religious publications.

On the last day of July 1863, Handy was dismayed by a conversation with an old acquaintance, a “brother minister” from Philadelphia. This was Rev. Dr. Thomas Brainerd, a Presbyterian clergyman who was visiting Fort Delaware. Known for his unflinching devotion to the Union and the United States government, Brainerd held the opinion that anyone who “ridicules and abuses the government of his country” was a traitor, and “should be dealt with as a traitor.” Handy wrote:

At the first sight of my old acquaintance, I extended my hand, and expressed pleasure in seeing him. He returned this cordiality in a manner exceedingly cold and distant; and in a tone of solemn reproof, he remarked:

“I am sorry to see you in this place, under such circumstances.”

“I am here,” said I, “for conscience’ sake—just as old John Bunyan was once a prisoner in Bedford jail.”

This remark produced a sort of momentary frenzy; and as he crossed the passage he trembled from head to foot.

“You are here,” said he, “for treason! You are a criminal and a bad man!”

Dr. Brainerd went on to “chide” and “condemn” Handy at length, and refused to listen to any of his objections or arguments in his own defense. Finally, Rev. Handy could bear no more.

“Dr. Brainerd,” I inquired, “what do you mean by this manner? Do you suppose I am a prisoner at this place from some foolish freak; that I am ignorant of the questions at issue; or that I prefer to suffer from some prejudice or bravado? You seem to think that all the wisdom is at the North, and that Southern people are all ‘know-nothings’ indeed.”

This response served only to excite him the more; and he ran on in a wild and ranting way—condemning the reading of the South as one-sided and full of prejudice, and urging that all the troubles of the country had been brought on by Southern preachers…

Handy assured him that “Northern newspapers were everywhere current at the South, and that Republican opinions, as expressed in the Herald, Tribune, and other leading journals in that section, were common in every village and hamlet of the Confederacy.” He went on:

On the other hand, I inquired: “Who reads a Southern newspaper at the North? Did you, Sir, ever see a Richmond, Charleston, or New Orleans newspaper anywhere in Yankeedom, out of a reading-room or some editorial sanctum?”

I insisted that “political sermons were the rare exceptions in Southern pulpits…How different…with your ministers at the North, who are constantly harping upon abolition, and the higher law! And what is even more preposterous, many of you preachers act as though they had the divine ipse dixit of the Almighty…saying, “I, the Lord God Almighty, have ordained the Government of the United States, as the only true and righteous government on earth; and whoso rebels against it, is not only a traitor to that government, but opposes my righteous will, and is subject, as an inevitable consequence, to my wrath and curse.”

“That is just what I believe,” replied the Doctor.

“Then, my brother,” I rejoined, “you are a fanatic, and greatly deluded…”

In the last week of October, Rev. Handy received some reading material that proved unwelcome:

Mr. Paddock, the Federal Chaplain, called and left some papers for distribution. I am very glad to get these weeklies; but never read them without having my feelings hurt—notwithstanding many good things they contain. It is especially painful to find religious journals opposing compromise, and rejoicing with malignant spite, in the purpose of subjugation or extermination. A correspondent of the Independent of October 15th says: “We are to bring this civil war to a close, not by compromise. Compromise, thank God, is impossible. It is to come by subjugation or extermination of the rebels, and in no other way.” Are they who thus teach disciples of the Prince of Peace? Are they not demons, belching forth the very spirit of the pit? Alas, for the age in which we live! The church is demoralized—the Christian name is too frequently a deceit—Christ’s members (?) are mad men! All this is literally true to a very great extent at the North.

In 1864, the United States government adopted a policy of retaliation against Confederate prisoners, reducing their rations. On June 22, 1864, Handy recorded in his diary:

Our rations are now a small piece of bread and meat, each, and a cup of water at breakfast; and at about four o’clock P.M. the same quantity of bread and meat…with the addition of a cup of rice soup. The soup is so bad—being often filled with flies and dirt—that I never use it…

Handy’s diary is replete with descriptions of the Confederate prisoners of war at Fort Delaware, and the difficult conditions there for them as well as the political prisoners. Though he regarded his imprisonment as unjust, he also believed that God could make use of him to bring good out of evil, and so he ministered to the spiritual welfare of his fellow prisoners. Soon after his arrival at Fort Delaware he began conducting daily worship services and regular prayer meetings. His services became so well attended that they eventually had to be moved outdoors to the larger open spaces of the prison yard. Handy became the president of the Christian Association of Fort Delaware, a group of prisoners who distributed Bibles and other religious literature among the inmates of the fort. He also started Bible classes and even formed a class to begin training men to become ministers. In the spring and summer of 1864, he wrote about a revival, or spiritual awakening, that became widespread among the imprisoned Confederate officers.

On October 13, 1864, Rev. Handy was released from Fort Delaware. Restored to his family and his native state of Virginia, the clergyman reflected on his ordeal, and in concluding remarks, he thanked God for his deliverance:

How strange the way by which God has led his servant! It was a way he knew not; but it was a way of blessing.

“The sorrows of death compassed me, and the pains of hell got hold upon me: I found trouble and sorrow. Then I called upon the name of the Lord; O Lord, I beseech thee, deliver my soul! I was brought low, and He helped me…O Lord, I am truly thy servant…and the son of thy handmaid. Thou hast loosed my BONDS!”