All-too-often, seemingly buried in the myriad dates and statistics of history, lies the human experience that should do more to make up that history in the first place. These eyewitness accounts and anecdotes seem to speak to us, across the ages, in ways that numbers do not (something historians might want to pick up on, if they want a revived interest in history). We’re able to connect with a person or people from the long past by putting ourselves in their shoes for a moment as we read of their experiences. In an age where “social” media and electronics have relegated family ties and oral tradition to the “back burner,” where can we turn? Can we manage a “resurrection” of sorts, of that campfire tradition that bound families together for generations? For those either living in, or having connections to, the Ozark Mountains of Missouri and Arkansas (and really any interested party) the answer lies, in part, with the writings of S.C. Turnbo.

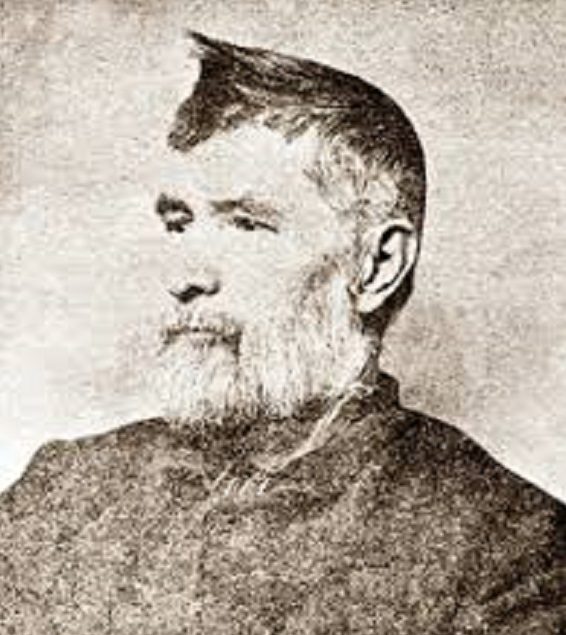

Silas Claiborne Turnbo or “Clabe”, as he was known to family and friends, was a self-described “Collector of History”. While he himself was very humble and unpretentious, his work is absolutely priceless when it comes to a modern-day understanding of the pioneer history of the Ozarks Region and the history of the War for Southern Independence in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

Turnbo was born, On May 26, 1844, into modest circumstances in the (then) wilderness near the town of Forsyth in Taney County, Missouri. But, early in his childhood, the family sneaked down the White River and across the state line and settled in Marion County, Arkansas. This area of the White River Valley was the “wild and woolly” frontier where basic necessities, animal hides and whiskey acted as currency and where the toughest (if not the meanest) man in the neighborhood was the most respected. Shootings, stabbings, and beatings over matters of honor, however trivial, were also commonplace. It was the edge of civilization, where men had not necessarily established their place on the top of the food chain and run-ins with bears, wolves and various species of large cat were frequent and deadly. At times, venison, turkey, and small game might’ve been more common table fare than pork and beef. “Clabe” tended to wander around a bit, but, he would stay along the state line, on one side or the other, for most of the rest of his life.

Out of the “hollers” and cane-choked river bottoms sprang numerous small subsistence farms and the small settlements became little, prosperous communities. James Coffee Turnbo and his family carved out a living raising corn, hogs and even apples on the banks of the river. The elder Turnbo also did a little trading with numerous steamboats that came up the river. The family was doing well for themselves by the outbreak of hostilities in 1861. In July of that fateful year, the forty-one-year-old “Jim” was elected Second Lieutenant of Company “C” of Colonel William Christmas Mitchell’s 14th Arkansas Infantry.[i] He would later resign his commission for health reasons.[ii] Seventeen-year-old Silas was neither old enough to enlist on his own or had permission from his father to do so and remained home as the first units from his county began to muster during that first summer. He chaffed under his obligation and even joined a small, hastily formed neighborhood watch of sorts. By the summer of 1862, however, he and the remaining neighborhood boys got their crops laid by and joined what became Captain Frederick T. Wood’s Company “A”, 27th Arkansas Infantry with Silas enlisting on June 26th, 1862.

What followed was three years of horror and privation that typified the trials and tribulations of the Confederate soldier and a young man experiencing the worst that life could throw at him. In the introduction to his History of the Twenty-Seventh Arkansas Confederate Infantry he summarized his service thus:

“I was a soldier on the Confederate side and … I served in the army west of the Mississippi River where the fighting was not so frequent and severe as it was on the east side of the ‘Father of Waters’. Nevertheless we tried to do our part of the struggle as it was allotted to us, and while we did not suffer so great in battle, yet we underwent much hardships of cold and hunger, sickness and death from exposure from marching over muddy roads and being exposed to the inclement weather.”[iii]

He further states in his 1907 application for admittance to the Confederate Home of Missouri at Higginsville that:

“[I] was with the army continually until the surrender. [I] was at the fall of Little Rock, Ark. Sept 10, 1863 [and] took part in the Battle of Jenkins Ferry April 30th, 1864, besides other battles of small importance. [I] was in all of the hard marches our regiment engaged in and faced all sorts of hardships. I was not wounded but my clothes was cut three times with bullets.”[iv]

His memoir, partially based on the one wartime diary that survived an 1866 house fire (and the rest from memory), is an almost daily account of his (and the regiment’s) service. Much like his other stories, his account is plainly written but thoroughly descriptive and often witty. Like many Southerners, he tried his best to inject humor into an otherwise atrocious situation. Aside from battle, he describes a day-to-day struggle to survive. Rations issued often consisted of spoiled beef and musty cornmeal and quantity was often an issue. Comrades were executed for desertion and mutiny. Picket duty was boring and exhausting and he was once thrown in the guardhouse and threatened with a firing squad after a pretentious officer claimed that he didn’t challenge his approach in a “prompt” manner. Company officers protested to the Colonel on his behalf, almost to the point of open revolt, and he was released. That Colonel was a strict disciplinarian, to the point of being tyrannical, and was appointed rather than elected. And, the majority of the men, including Turnbo, despised him from the very start, until well after he was voted out in late 1863. Dysentery, malaria, yellow fever, and pneumonia killed more than battle did and the elements were harsh. On a particularly terrible day, which he described as the most terrible that the regiment ever endured, the men marched seven miles through flooded river bottoms, in water up to waist deep, during a snowstorm. Those hard marches and terrible experiences are all included in vivid, brutal detail. But the sense of adventure, fascination and gallows humor never left his reminiscences, either, and Turnbo saw muchof the vast expanse of the Trans-Mississippi Theater – occasionally from the decks of a steamboat or while riding on a flatcar of a train. He and a couple of comrades might’ve broken discipline a tad and “appropriated” a farmer’s wandering pig during a time of particularly, lean, poor rations. The boys had a particularly rambunctious frolic on Christmas Night of 1863 and, in the summer of 1863, their officers made the decision to stop the boys at a distillery and get the boys drunk in an attempt to drive out malaria. The classic description of decks of cards being strung along a line of march before battle makes an appearance, as well. As do so many other vignettes which have become stereotypical of the Confederate soldier’s experience.

As for full-scale battle, well, it seemed to elude Turnbo and his comrades time and again. Only half of the regiment was armed at the outset of the Prairie Grove Campaign, in December of 1862, and those “armed” had shotguns and squirrel rifles. Seeing no other solution, their Colonel requested to have his regiment withheld from the coming fight and his request was granted.[v] The men were sent back to guard the Army’s supply trains and could hear the artillery fire as the battle was fought. On the retreat towards Little Rock, after that battle, the 27th was part of a rearguard action outside of Van Buren, Arkansas which exposed the boys to their first real taste of battle: an artillery barrage. He describes the helpless feeling of being forced to simply lay down and endure the shelling complete with the noises the shells made as they flew over, threw dirt and broke tree limbs. During the Vicksburg Campaign, the regiment was part of a small task force sent to raid outlying Federal outposts and supply depots in an attempt to loosen their grip on Vicksburg during the siege, there. A few extremely minor clashes were taken part in but nothing of substance. During a cavalry battle to prevent the Yankees from taking Little Rock, the regiment took some long-range artillery fire but otherwise had to undergo the humiliation of giving up their capital without much of a fight.

When Turnbo and his comrades did encounter heavy fighting in the spring of 1864, however, it was intense and bloody. He was sick in the hospital in Jefferson, Texas when the boys fought at the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9th. His only mention of that affair is that, upon reuniting with the regiment, the boys mentioned some of their casualties. The Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry on April 30th, on the other hand, is very thoroughly described. This account, of his only major battle, has prose enough to content the novelist and facts enough to meet the historian’s standards. He recounts what he saw, from a private’s perspective, in almost precise detail (as his memory served) including the whistling of the minié balls and the thuds they made as they hit his friends. He mentions the bravery and determination of his fellow soldiers and leaders, even in the face of a bloody, unsuccessful attack. Whether he meant to, or not, he makes a subtle nod to future academics and historians in that, in a fairly unique step for a rank-and-file memoirist, he was actually willing and able to take time to pour over the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion in the library during his stay at the Confederate Home. In his manuscript, he even compared and contrasted what he witnessed during the battle with what his brigade commander had written, forty-three years before.[vi] All of the familiar themes of combat, in the War for Southern Independence, are there and his recollection is probably the most thorough of an enlisted participant of the battle. That was the end of his combat experience and the 27th spent the rest of the war garrisoning different points in Southern Arkansas, Northern Louisiana and Eastern Texas.

With the demobilization of the Confederate Armies and the ending of the war, the skeletal remnants of the 27th Arkansas were paroled at Shreveport on June 8th, 1865. There they began a hundreds-mile-long journey on the steamboat “Colonel Chapin” that took them down the Red River to the Mississippi, up the Mississippi to the White River and up the White as far as summertime water levels would allow, which happened to be Jacksonport, Arkansas. From there Turnbo and two comrades continued on foot with Turnbo having the furthest to go (about one hundred miles) and the other two splitting off with about thirty to go.

After arriving back in Marion County, he reunited with his family and helped them begin to reassemble their shattered prewar lives. He, his father and brothers managed to harvest a corn crop at the end of that first summer and that December wrangled an old sow pig of theirs that had wondered off.[vii] Times were hard, but the Turnbo clan had a decent start compared to a lot of folks. In January of 1869, he married a neighbor girl, Mary Matilda Holt. Together they would have five children and she would follow him through most of the trials of his life before dying a little under three years before he did in 1922.

It is unclear when he began collecting stories but by the turn of the century he was putting them to paper. In them he often cited conversations, that he had with people decades before, as the source for this story or that. He made it a point to track down old acquaintances and old pioneers of the area and ask them to share stories from what he considered the “early days.” What he ended up compiling is a veritable “treasure trove” of fascinating, sometimes unbelievable stories about encounters with animals, wartime incidents and atrocities and day-to-day life in an untamed wilderness. All of this was recorded in very plain language, easy to understand but with some very interesting grammar and run-on sentences. He wrote as if he was telling you the story. His stories are full of big cats, deer, bears, wolves, snakes, and a host of odd natural occurrences not mentioned anywhere else. A sampling of some of his work would be proper, here:

The story “Hunting Squirrels and Killing a Huge Panther” is a thrilling tale about four young boys of the Barber Family having the encounter of their lives in Christian County, Missouri in 1847. The four lads were squirrel hunting with a pack of dogs when the dogs ‘treed.’ Assuming the dogs had found a squirrel, the boys rushed forward to find a rather large, enraged feline awaiting them. The boy with the rifle, merely ten years old, coolly aimed and shot the beast as it sprang out of the tree. Severely wounded but still capable of fighting, the “panther” began to battle the dogs but was finally put down by another well-aimed shot by the lad. They later sold the hide which was kept on display, in Springfield, for several years.[viii]

Another humorous, exciting, and rather bizarre tale involved a postwar deer hunt by neighbor and fellow Confederate Veteran Abe Perkins. Like the rest of the South, things were pretty lean in the Ozark Hills in the aftermath of the war. Mr. Perkins, whose family was then dependent on wild game to feed themselves, had managed to scrounge up some ammunition for his old rifle and set out to get some venison. Less than a mile from the house he encountered a buck sharpening his antlers on a tree. Taking careful aim, he shot the deer, wounding him. But the blow was not mortal, and the buck, spotting him, “flew into a terrible rage” and charged at his would-be assassin. Abe frantically dropped his rifle and ran for the nearest tree getting into it just in time to miss the antlers of the charging buck. By now, the family dog had been alerted to Abe’s frantic “hollering” and rushed to his defense, but the buck made short work of him by pinning him against a tree and goring him to death. Next, came Abe’s wife Nancy who rushed out only to find herself chased and treed by the deer! Abe realized that the animal was distracted and climbed back down the tree, got his gun and shot the animal a second time, killing him.[ix]

Aside from incredible wildlife, Turnbo also recorded stories of the wartime struggles of the region’s inhabitants. One man remembered his father reading the Bible by the light that was given off by the burning of Huntsville, Arkansas, by Federal troops.[x] Another, a Union man living in Douglas County, Missouri, was awakened one night by Confederates from Greene County who had lost their way in a dark, unfamiliar country and were politely requesting a guide to direct them to friendly lines. [xi] Still others went into great detail about murders, robberies and other savagery taking place in a deeply divided region where neighbors turned against each other and both sides did their fair share of foraging. Even large bodies of troops simply stopping to drink at a spring[xii] or reminiscences about where they camped[xiii] were recorded with Turnbo himself, at times, being the one reminiscing.

Even more important to some are his brief histories of pioneer families in the area. At a time when people were both very knowledgeable and very proud of their family roots, “Clabe” clung to every particular. Birthplace, ancestry, immediate family, marriage and even the burial place of his sources tend to find their way into the introduction of almost every one of his stories. He could probably give the Gospel of St. Matthew’s first chapter a healthy competition in genealogical detail!

He spent most of the latter years of his life attempting to get an interested publisher to buy his writings. He self-published two volumes of his Fireside Stories of The Early Days in the Ozarks in 1905 and 1907, respectively. He sold them for fifty cents a piece but they weren’t massive hits. He wrote columns for several regional papers using the stories that he had collected. In 1905, he began an almost decade-long correspondence with publisher William Connelly of Topeka, Kansas. Connelly seems to have been genuinely interested in the stories that Turnbo had collected but appears to have been more interested in stringing Silas along while occasionally providing him with books that he had published. Broke, aging and in declining health, Silas bounced around the region staying at the Confederate Home in Higginsville and with family and friends in Missouri and Oklahoma. He even went as far as New Mexico to stay with a son in 1913. It was in New Mexico that, in dire straits, “Clabe” sold the rights to his entire collection to Connelly for a fraction of its worth: $27.50 – The price of train fare back to Oklahoma. What else could be expected from William Connelly, who wrote Quantrill and the Border Wars – a highly propagandized, inaccurate account of the conflict between Missouri and Kansas that made Missourians out to be Satan’s minions and made Kansans out to be saints?[xiv]

Turnbo continued to move around and collect stories until his death near Tulsa, Oklahoma, on March 15th, 1925 at age eighty. He’s buried in Park Gove Cemetery in Broken Arrow.[xv] Family lore has it that his remaining writings were wrapped in oil cloth and buried with him to prevent it from falling into the hands of William Connelly, who they felt had cheated him.[xvi] Upon his death, Connelly donated a substantial amount of his papers to the Kansas State Historical society and this included what he had previously purchased of Turnbo’s work. By the 1970s, however, and through a series of exchanges including a city ordinance, the Springfield-Greene County Library acquired his manuscripts and have made them available both in-person and digitally. Over eight-hundred stories have been transcribed and are available online, for free, on the library’s website. Additional published collections include transcriptions published by category and a fantastic anthology of hand-picked stories, photographs, contextual information and even a map entitled The White River Chronicles of S. C. Turnbo: Man and Wildlife on the Ozarks Frontier edited by James F. Keefe and Lynn Morrow.[xvii]

Probably the most fitting aspect of the legacy of S.C. Turnbo’s work is that a majority of his homeland is under water. The White River was dammed up in 1951, creating Bull Shoals Lake and tragically flooding most of the farms, homeplaces, towns, cemeteries, and other points of interest that he mentions in his writings. It is a world displaced by both time and nature harnessed by industrialized man. This backwater is now underwater. In drought years, displaced towns like Old Lead Hill can be found by old chimneys “peeking” at passing fishermen from just above the waterline. Interestingly enough, the last publicly operated ferry in the State of Arkansas crosses the White River channel very near to “Clabe’s” submerged homeplace. He probably would’ve found that a curiosity.

Silas Turnbo would hardly be welcome at any conference of lettered academic historians. And he’s been largely forgotten with the exception of a relatively small group of devotees (if not outright fanatics) who are dedicated to his memory for his contributions to their family histories or to the culture and memory of their home territory. Historians, genealogists, hunters, fishermen and other outdoor adventurers all have something to gain by reading his work. His writings are essential for those wishing to understand the Frontier South encompassed by the Missouri and Arkansas Ozarks. His stories may seem outlandish, antiquated, or extraordinary to some. But there is, occasionally, an echo from the long-forgotten past. In 2019, a Marion County, Arkansas man made national news after being tragically killed by a buck he had shot. He was using a single-shot muzzle loader and had merely wounded the animal when it charged him and gored him. Arkansas Game and Fish officers were stunned and remarked on how odd the incident was. Many of the public had never heard of such a thing.[xviii] This incident occurred right in the heart of Turnbo’s home county, and, while certainly sad and tragic, should’ve been no surprise to those who had read and knew their Turnbo.

[i] Civil War Service Records (CMSR) – Confederate – Arkansas – Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration and Fold3.com

[ii] History of the Twenty-Seventh Arkansas Confederate Infantry, by S. C. Turnbo and Desmond Walls. Allen, Arkansas Research, 1993, p. 13.

[iii] Ibid p. 9

[iv] “Missouri, Confederate Pension Applications and Soldiers Home Applications, 1911-1938,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939V-559Z-LB?cc=1865475&wc=M8VQ-QTL%3A168966001%2C169518401 : 12 November 2020), Soldiers Home Applications – Approved > Stith, Geo H. – Troyman, Geo B. > image 462 of 510; Missouri State Archives, Jefferson City.

[v] Shea, William. Fields of Blood: The Prairie Grove Campaign (Civil War America). 1st ed., The University of North Carolina Press, 2009. p. 111.

[vi] Turnbo p. 108

[vii] Ibid p. 141-142

[viii] Turnbo, Silas. “Hunting Squirrels and Killing a Huge Panther.” The Turnbo Manuscripts, Springfield-Greene County Library, thelibrary.org/lochist/turnbo/V10/ST347.html. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

[ix] Turnbo, Silas. “A Wounded Buck Creates a Scene.” The Turnbo Manuscripts, Springfield-Greene County Library, thelibrary.org/lochist/turnbo/V8/ST278.html. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

[x] Turnbo, Silas. “Reading The Bible By The Reflection of Light From a Burning Town.” The Turnbo Manuscripts, Springfield-Greene County Library, thelibrary.org/lochist/turnbo/V1/ST016.html. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

[xi]Turnbo, Silas. “Guiding Five Southern Men to Safety After Night.” The Turnbo Manuscripts, Springfield-Greene County Library, thelibrary.org/lochist/turnbo/V3/ST070.html. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

[xii]Turnbo, Silas. “A Company of Confederate Soldiers Drinking Water in War Times on George’s Creek.” The Turnbo Manuscripts, Springfield-Greene County Library, thelibrary.org/lochist/turnbo/V2/ST038.html. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

[xiii] Turnbo, Silas. “The Old Winter Quarters of Colonel Mitchell’s Regiment of Confederate Soldiers of the Winter of 1861-2.” The Turnbo Manuscripts, Springfield-Greene County Library, thelibrary.org/lochist/turnbo/V2/ST049.html. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

[xiv] Morrow, Lynn. “‘I Am Nothing But A Poor Scribbler’: Silas Turnbo and His Writings.” White River Valley Historical Quarterly, Spring, 1991, pp. 3–9.

[xv] “Silas Claiborne Turnbo.” Https://Www.Findagrave.Com/Memorial/5966867/Silas-Claiborne-Turnbo, Find-A-Grave, www.findagrave.com/memorial/5966867/silas-claiborne-turnbo. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

[xvi] Berly, Juanita. “Silas Claiborne Turnbo.” The US Gen Web Project, www.argenweb.net/marion/stories/silas-turnbo-biography.html. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

[xvii] “Bibliography – Works by and About S.C. Turnbo.” The Library, The Springfield Greene County Library, thelibrary.org/lochist/turnbo/TurnboBib.html. Accessed 3 Dec. 2020.

[xviii] Sinnett, Caitlin. “Hunter Dies After Deer Attacks Him in Marion County, Ark.” KY3, KY3 News, 23 Oct. 2019, www.ky3.com/content/news/Hunter-dies-after-deer-attacks-him-in-Marion-County-Ark-563748531.html.