Introduction

This is James Johnston Pettigrew’s only book, privately printed in Charleston in the first weeks of the War between the States and here for the first time published. In the opening passage the author describes himself crossing the Alps on his way to seek service in the army of the king of Sardinia. His mission was to take part in a struggle for liberty, the liberation of Italy from the yoke of Austria.

That was 1859. By pure chance it was the Fourth of July, not only the birthday of American independence but also, as it happened, Pettigrew’s own birthday, his thirty-first. Exactly four years later (the Fourth of July 1863), he was beside the Emmitsburg road near a Pennsylvania town called Gettysburg, nursing a useless right arm which had been smashed by grapeshot and waiting for an enemy counter-attack that never came.

All about him were the survivors of the North Carolina soldiers that the day before he had led through a mile of frontal and flank fire to within a few yards of the now eternally famous stone wall on Cemetery Ridge. Pettigrew was, by his own lights, engaged in another struggle for liberty, that of his own people from a Union that had grown hateful. Two weeks later, he was dead of a wound received in a minor skirmish as the rearguard of the Army of Northern Virginia recrossed the Potomac back to the Confederacy.

In 1859 Pettigrew had caught up with the allied Sardinian and French forces in northern Italy just a few days after the decisive battle of Solferino. In that battle the French had broken the Austrian center, posted on a ridge, by an attack across a wide expanse of open land—an uncanny resemblance in terrain and action to the third day at Gettysburg, as any visitor to both places will see and as Pettigrew must have noticed. The open ground covered by the French charge was a bit steeper but also shorter than that to be covered by Confederates on July 3, 1863. And of course, unlike the Confederates at Gettysburg, the French were successful.

The author’s early death, along with the time and circumstances of its printing, explain in part why his book has been nearly unknown. Another reason is the title, which does not give much of a hint that it belongs in the domain of Southern literature, but places it, apparently, in the rather perishable category of travel books. Notes on Spain and the Spaniards is, in fact, an extremely interesting product of the intellect of the late antebellum South, which accounts for its publication in this series.

The Author

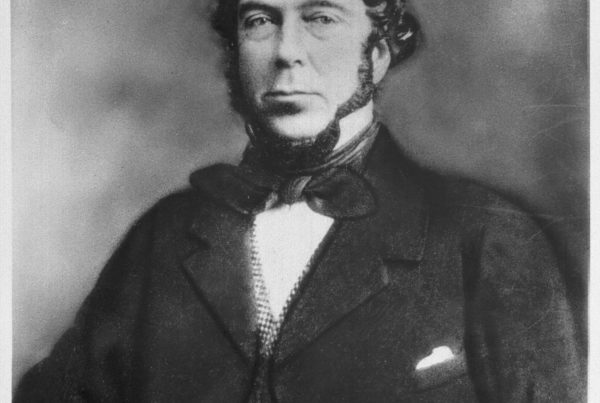

James Johnston Pettigrew was born on 4 July 1828 at Bonarva plantation in Tyrrell County, North Carolina. He was the sixth of seven children of Ebenezer Pettigrew, a pious, hard-working, and very successful planter, and Ann Blount Shepard Pettigrew, who came from a prominent New Bern mercantile family. There is an apocryphal story about a proud man who refused to serve in Congress because it was no place for a gentleman. This was quite literally true of Ebenezer Pettigrew, who, after one term in the House of Representatives, never set foot in Washington again. The son inherited the father’s idealism but not his disdain for public action.

While he was still a child his relatives observed that Johnston (as he was usually called) enjoyed exceptional mental gifts. The end result was that, while two older brothers inherited plantations, the youngest’s legacy was the best available education and a portion of capital sufficient to allow him to become established in a profession.

He attended Bingham’s academy in Hillsborough, considered the best school in the state, and the University in Chapel Hill, from which he was graduated at eighteen first in his class with a perfect academic record. Among visiting dignitaries at the Chapel Hill commencement of 1847 were President James K. Polk, an alumnus, and Lieutenant Matthew F. Maury of the Navy, already gaining international reputation as an astronomer and oceanographer. They were so impressed with the mathematical genius of the valedictorian that Pettigrew was on the spot offered a “professorship” at the Naval (or National) Observatory, of which Maury was superintendent. Maury was later to refer to Pettigrew as “the most promising young man of the South.”1

After six months as an astronomer at the Observatory (now the official residence of the Vice President), Pettigrew left to study law in Baltimore under a son-in-law of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney. In 1849 he was offered a position as a junior partner in the Charleston practice of James Louis Petigru, one of the foremost members of the South Carolina bar and his father’s first cousin.

Before he began this professional career, there occurred the period of the author’s life that is the most interesting for the present occasion. From January 1850 until August 1852 Pettigrew was in Europe, enjoying experiences that were available to few Americans, and of which he made the most.

The first year was spent at the University of Berlin, from which Pettigrew acquired a degree in Civil Law. For the rest of his time in the Old World, the young Carolinian went native, traveling and living in Germany, Austria, Bohemia, Hungary, Italy, France, Britain, and Spain. Much of his travel was off the beaten track of tourists, afoot or on horseback. For long periods Pettigrew cut himself off from all American contact and mingled with the people.

As is documented in his diaries and letters, abundantly preserved at Chapel Hill, he became proficient in German, French, Spanish and Italian, both spoken and written, and in written Arabic and Hebrew. He immersed himself, as is clear from his book, not only in the history and culture of Europe—the relics of antiquity and the Middle Ages, the scholarship, art, architecture, and battlefields—but also in the contemporary life of various classes and several countries.

One result was a lasting admiration for the Latin peoples, especially the Italians and Spanish, which was quite unusual for an English-speaking tourist of the time. “In proportion as we approached Italy,” he once wrote, “my feeling of satisfaction arose; I felt as I used to do on leaving the Yankee land on the way to the South. At almost every railway station, one could perceive an increase in the beauty of the women, in the sociability of the men, and in the smiling genial aspect of the country.”2 (One is reminded a bit of Faulkner’s Quentin Compson crossing Mason and Dixon’s line on the train from Harvard.) So well did Pettigrew fit in that he found, to his delight, that Englishmen often mistook him for a Frenchman or Spaniard.

The last months in Europe were spent in southern Spain, a period which Pettigrew described as the happiest of his life. He formed the project of writing a scholarly history of Arab contributions to the civilization of Europe. The work was never written, but Notes on Spain and the Spaniards contains many intimations of what it might have been. This is another characteristic that makes republishing this book timely, as we live today amidst a renewed conflict of the West and Islam. Another historical enthusiasm was the career of the Carlist general Tomas de Zumalcarregui, a sort of Spanish Francis Marion.

On his departure from Europe, in an inaccurate prophecy but a revealing sentiment, Pettigrew wrote his sister: “Alas! Romantic Spain, I shall never see thee again. By the bye I have not a portion of heart remaining as large as a pea. The whole is left in Andalusia . . . .”3

Pettigrew spent the rest of the 1850s in Charleston, a city which, as a modest North Carolinian, he at first found to be distastefully fashionable and self-important. But as he was adopted by the extended family of James Louis Petigru, Charleston became more congenial. He practiced law, engaged in politics, wrote for the newspapers, nearly died of yellow fever, was a second in a notable duel, and was regarded as an eccentric genius and a somewhat eligible bachelor. He pursued intellectual interests in the company of the historian William Henry Trescot and the theologian and linguist James Warley Miles. In 1856–1857 he served a term in the South Carolina House of Representatives. At that time he acquired a brief national reputation for writing a committee report that killed a foolish and provocative proposal for re-opening the African slave trade which Governor James H. Adams had put forward.

Pettigrew’s family politics was moderate Whig, critical of fire-eaters and secessionists and inclined to ignore rather than respond in kind to Northern attacks. But, characteristically for his generation, he became convinced that sectional war was inevitable and undertook to prepare himself for a creditable part in it. He participated actively in the militia and studied it closely. One result was “The Militia System of South Carolina,” probably his most important writing after Notes on Spain, which was published anonymously in Russell’s Magazine.4 It was an extended, good natured but biting, satire of the delusion that South Carolina was prepared for military defense. At the same time Pettigrew took every opportunity to make himself a model officer, not neglecting artillery, engineering, ordnance, sanitation, supply, and cookery.

In 1859, when news was received of war in Italy, Pettigrew made his will, purchased equipment, and hastened to New York to take ship. He reached Italy as he describes herein. He was able to get an interview with a secretary of Count Cavour, the Sardinian prime minister, to whom he declared that he wanted to serve as a volunteer in action and did not expect either a commission or pay. Unfortunately for him, a truce had been declared just a few days before, after Solferino, and the allies had acheived their immediate goal of releasing Lombardy from the Austrian grasp.

Disappointed in the hope of participating in, or even witnessing, battle, Pettigrew went to Paris and spent some time learning from French officers as much as he could about military art and science. Then he went again to Spain, the pilgrimage he records in Notes on Spain and the Spaniards.

From the secession of South Carolina in December 1860 until the surrender of Fort Sumter the following April, Pettigrew was active in Charleston harbor as Colonel of the state First Regiment of Rifles, the elite infantry formation of the new state army. Soon after, he was informed of his election as Colonel of what became the 22nd North Carolina Regiment, which he hastened to Raleigh to join. This regiment guarded the Potomac in the vicinity of Fredericksburg from the summer of 1861 to the spring of 1862. In March 1862 Pettigrew learned that he was appointed a brigadier general. He refused promotion, arguing that no one should hold that rank who had not had combat experience. He was called to Richmond for a conference with an amused President Jefferson Davis, who remarked that this was the first time anyone had ever refused a promotion on the grounds of inexperience.

He was finally persuaded to accept the post. The impression Pettigrew had made is indicated by the fact that there were very few generals at that time who were as young and who were not former U.S. Army officers or powerful politicians. On 31 May 1862 Pettigrew went into action at the battle of Seven Pines, the first engagement of the Peninsular campaign. Leading an attack, he received three wounds and was left on the field for dead, behind enemy lines. He was not dead, though unconscious, and was picked up by a party of federal soldiers which included the future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Imprisoned at Fort Delaware, Pettigrew was believed dead in the Confederacy and had the unique experience of reading his own obituaries.

Some weeks later he was exchanged and, though still partly disabled, returned immediately to duty. He assumed command of a newly formed North Carolina brigade, which from the summer of 1862 till the spring of 1863 took part in a number of small battles with federal occupying forces in eastern North Carolina. On June 1, the brigade joined the Army of Northern Virginia on the move to Pennsylvania. On the march north Pettigrew wrote to Governor Zebulon B. Vance his hope that “peace is to be conquered this summer.” To a relative he wrote of the Confederacy: “In the midst of all our trials it is a consolation to reflect, that our reputation, next to Greece, will be the most heroic of nations.”5

Pettigrew’s role in the battle of Gettysburg is sufficient to guarantee him at least a small place in history. His brigade made the first, unexpected contact with the federal army near the town on June 30. The next day it played the key part in a bloody advance which drove the enemy from McPherson’s and Seminary ridges and in the process smashed out of existence the Iron Brigade, thought to be the best in the Union army. On July 3 Pettigrew’s men were called upon again to advance against a heavily defended position, a failed action which they carried off as bravely as Pickett’s previously unbloodied division which has given a somewhat misleading popular name to the historic charge. The casualties in his brigade were among the heaviest for a few days’ fighting in the entire war on either side.

During the withdrawal, on July 14, Pettigrew was shot in the stomach when a straggling company of federal cavalry rode by accident into a group of officers of the rearguard, at Falling Waters, Maryland, on the north bank of the Potomac. Pettigrew was told that his only hope of life was to remain behind, immobilized, to the care of enemy surgeons. He insisted on staying with the army and was carried for three days in a litter, dying on July 17 at Bunker Hill, (West) Virginia.

“None had more deeply at heart than he the cause for which he shed his blood,” wrote a former British army officer who served under Pettigrew. “I tell you the truth when I say that I have never met with one who fitted more entirely my ‘beau ideal’ of the patriot, the soldier, the man of genius, and the accomplished gentleman.” According to Douglas Southal Freeman: “For none who fought so briefly in the Army of Northern Virginia was there more praise while living or laments when dead.”6

The Book

By the author’s own account, Notes on Spain and the Spaniards was begun in Charleston in the spring of 1860 in time spared from law practice and militia drill. He regarded the writing to be chiefly for his own benefit, “an offering in memoriam of the happiest days of my life.” By June 1860 the manusacript was completed and put aside. Exactly a year later, in the interim between the surrender of Fort Sumter and departure for the Virginia front, Pettigrew took out the manuscript and had it printed at his own expense, using his salary from service as colonel in the state army. Three hundred copies were printed. One hundred of these were bound, to be given to relatives and friends.7

The work was at this stage was intended for private circulation, though the author’s introductory note seems to suggest an intention for future publication. The title page identified the author only by his initials and the title “A Carolinian.” According to the bibliographic research of Patricia T. Thompson and Alexander Moore, about fourteen institutions (including two in Boston) hold copies, with multiple copies at the University of North Carolina. It seems likely that the unbound copies have perished, for Charleston suffered two major fires and a 587-day bombardment and siege in the few years after the printing.

A few scholars in the two Carolinas—both could claim Pettigrew—of the author’s generation and the one following noticed and wrote about the book. Their comments were cogent, specific, and complimentary, and it becomes all the more surprising that the work dropped totally out of sight after the early twentieth century.

Reading and critical comment began with some of those who received copies. “Very clever and very like himself,” wrote one relative of Pettigrew. James Louis Petigru, a man of considerable learning, said that his opinion of the work rose on each re-reading.8 William Henry Trescot, one of the friends who received a copy, wrote in a memorial of Pettigrew soon after the war:

“This book is admirably written. The country and the people whom he described had for him a romantic charm, and his enthusiastic sympathy with their history and character gives to his descriptions a warmth and truthfulness which a colder observation could never have imparted. His thorough knowledge of Spanish history and his familiarity with the language taught him both what to observe and how to observe.”9

In 1875, Theodore Bryant Kingsbury, who had been a fellow student of Pettigrew at Chapel Hill and who was like Pettigrew a seasoned European traveler, wrote an appreciation of the work for a Southern magazine. “On every page is revealed the scholar, thinker, and keen observer,” said Kingsbury, “whilst we have frequent gtlimpses of a statesman and philosopher at home among the social and political systems of the Old World.”

He described Notes on Spain, correctly, as “fresh, witty, vivacious, thoughtful, kindly” and “distinguished by a catholic and generous spirit quite uncommon among travelers.” Further, the “book has been rather a surprise to us…. There are occasional passages of a humorous turn that we were not prepared to meet with. It is, besides more artistic, hearty and eloquent, than we anticipated.” Kingsbury doubtless had in mind such humorous passages as Pettigrew’s treatment of Charlemagne as a filibusterer and his self-satirical description of renting a mule from villagers in the Pyrenees. Kingsbury proposed that Notes on Spain was more lively and learned and less prejudiced than any of the popular travel books by Northerners.10

In 1887 Cornelia Phillips Spencer, a well-known North Carolina writer of the time, whose father and brother had taught Pettigrew at Chapel Hill, published an essay called “General Pettigrew’s Book.” She had evidently been presented with a copy by the General’s brother William. While complimentary, she was somewhat irritated at Pettigrew’s fondness for the Latins and contempt for the Mother Country, Britain, which, she said, “to deride and depreciate which he omits no opportunity.”11

Notes on Spain and the Spaniards was next noticed by Ludwig Lewisohn, a minor critic, while writing a series on South Carolina literature for the Charleston News in 1903. “Pettigrew’s single book is as interesting a volume of its kind as one can well imagine,” he wrote. Lewisohn observed that Pettigrew had a very high potential as a writer and regarded it as a flaw of the old regime in the South that he had not developed his talent further.12 In this Lewisohn was in keeping with the scholarly consensus of the time. William Peterfield Trent had put forward a similar theory in an 1892 biography of William Gilmore Simms.

In the multi-volume Library of Southern Literature, published in 1908-1913, Pettigrew was included, with excerpts from the book and a critical sketch by Nathan W. Walker, professor at the University of North Carolina. Walker wrote:

That the author had the temperament of the man of letters, and possessed literary ability and skill of a high order, will readily be seen by even a glance at his work. Large tolerance and intellectual flexibility are everywhere apparent, and one realizes here and there the touch of the master’s hand and feels that nothing could be finer than some of his descriptive passages. Deep poetic feeling and imagination, delicate humor, refined wit, a “rare gift for the happy word,” are some of the author’s ear-marks.13

Walker’s selections reflected the artistic descriptive passages of the book: the author’s reaction to the Seville cathedral and the Catholic piety observed there, to the charms of Spanish ladies, and to the Alhambra, the last a subject already made familiar to American readers by Washington Irving

Other than my study of Pettigrew (dissertation, 1971; book, 1990), Walker’s seems to be the last notice taken of this book, with one exception. A 1973 novel, The Killer Angels, describes an intellectual General Pettigrew presenting a copy of a book he had written to General James Longstreet during the battle of Gettysburg. This scene, entirely fictional and extremely unlikely, was adapted into the film “Gettysburg.”

The testimony of these critics should be enough to establish Notes on Spain and the Spaniards as a work of sufficient interest to deserve attention. It does what every good book does—present an interesting mind at work on interesting material. It is readable and gives nourishment for thought. Pettigrew records a journey that is not only geographical and contemporary. It is a historical, aesthetic, intellectual, political, and spiritual odyssey. His experiences, impressions, and judgments are sincere and rendered with considerable art. The work is at the same time a travelogue, an exploration of Spanish history and manners, and a defense of Spain from the prejudices of “Anglo-Saxons.” For him the Anglo-Saxons were the North and the Spaniards the South.

More importantly, the book exhibits the well-developed social philosophy and worldview of a late antebellum Southerner, an exhibition of elements different from those usually assumed to characterize Pettigrew’s society.

About 1970, when I first began to study James Johnston Pettigrew and his forgotten book. I remember feeling strongly an existing scholarly neglect and condescension in regard to the intellectual life of the Old South. Few scholars, it seemed, took Southern thought seriously, with some exceptions in regard to a few conspicuous pro-slavery writers. Despite the inherent implausibility that nothing of interest had been written between Thomas Jefferson and William Faulkner, the intellectual life of the 19th century was dismissed as of insufficient quantity and quality to merit consideration.

The case is rather different nearly forty years later. In the intervening period there has been a lot of historical examination of the mental life of the Old South—its creative literature, theology, education, and political, social, and economic thought. The preponderance of scholars who know something about the subject are now aware that the Old South had an intellectual culture interesting in kind and amount, and that no sharp division could be drawn between the antebellum South and Revolutionary and early national ideas. Pettigrew is an example of the latter fact, being in sum as much an early Republic classicist as a 19th century romantic. The South had men and women, not insignificant in numbers and talents, actively reading and writing, abreast of the world of ideas past and current, and thinkling about subjects other than the immediate politics of their peculiar region.

Neglect if not condescension has disappeared and the intellectual life of the antebellum South is now, in fact, a substantial element in Southen historiography. Such writers and thinkers as William Gilmore Simms, James Henry Hammond, Henry Timrod, George Frederick Holmes, Beverly Tucker, George Tucker, Henry Hughes, Louisia Cheves McCord, Mary Boykin Chestnut, Augusta Jane Evans Wilson, James Henley Thornwell, Robert Lewis Dabney, and others have received extended treatment.

Much though not all of this literature is characterised by the same implicit assumptions that have always dominated fashionable writing about Southern history. That everything, even what appears to be intellectual or creative accomplishment, is to be explained in terms of irrelevance, evil motives, warped personalities, guilt, self-delusion, or at best a crypto-fifth column rebellion against the regime. Johnston Pettigrew’s encounter with a perennially out-of-step European country provides its own unique insight into the Southern mind on the brink of a struggle for independence.

Notes

(1) Maury to Mary Pettigrew Browne, 6 May 1870, Pettigrew Family Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (SHC).

(2) Pettigrew to James C. Johnston, 15 March 1851, SHC

(3) Pettigrew to Ann Pettigrew, 10 June 1852, SHC

(4) Russell’s Magazine 6 (March 1860): 529–540

(5) Pettigrew to Gov. Zebulon B. Vance, 22 May 1863, Governors Letterbooks 50.1, 255-256, North Carolina Department of Archives and History (NCDAH); Pettigrew to Jane Petigru North, 19 May 1863, SHC

(6) Collett Leventhorpe to Mary Pettigrew, 14 May 1867, Pettigrew Family Papers, NCDAH

(7) Pettigrew to William S. Pettigrew, 18 June, 1861, SHC. Copies have been identified that were given by the author to Trescot, a South Carolinian and pioneer diplomatic historian; sister Mary Blount Pettigrew; maternal “Grandma” Mary Blount Shepherd; a cousin, Louise Petigru Porcher; Ellison Capers, a Charleston intellectual colleague, later a Confederate brigadier general and Episcopal bishop; and Louis G. Young, Pettigrew’s aide during the war. There also exists one unbound copy on which someone, not Pettigrew, has made numerous inexplicable corrections.

(8) Minnie North Alston to Caroline North Pettigrew, 17 July 1861, and James Louis Petigru to Pettigrew, 24 June 1861, SHC

(9) Trescot, Memorial of the Life of J. Johnston Pettigrew . . . (Charleston: John Russell, 1870): 42-43

(10) Our Living and Our Dead 3 (December 1875):784-785

(11) “General Pettigrew’s Book,” University of North Carolina Magazine 6 (March 1887): 267-268

(12) “A History of Literature in South Carolina, Chapter 11: Pettigrew and Trescot,” Charleston News, 30 August 1903

(13) Library of Southern Literature (Atlanta: Martin & Hoyt, 1908-1930), vol. 9, p. 3984

SOURCE: Introduction to NOTES ON SPAIN AND THE SPANIARDS, by James Johnston Pettigrew. New edition, University of South Carolina Press, 2010

(Author’s original version before publisher’s editing)