Filmmaker Arlen Parsa has recently undertaken a project that blots out the faces of all the signers of the Declaration of Independence in John Trumbull’s famous painting “The Declaration of Independence.” The stunt has unsurprisingly gained the filmmaker much notoriety. While the project might seem to have been a frivolous undertaking for Parsa—something to pass the time in these Coronavirus days—that is doubtful. Parsa did not just check off the slaveholders in the picture, he blotted out their faces. That move speaks volumes for the delitescent point he was aiming to make. Those signers of the document who owned slaves were evil men, and he, by blotting out their faces, stands above them as their moral superior.

There has been a trend in history in the past few decades that theses that might help to mend the strained relationship between the races in this country by “tweaking” the truth tend to get published and win celebrity for their authors, while theses that describe the history of America’s racial past as it happened and from the perspective of those persons living in the past are rejected. Arlen Parsa’s project, though he is no historian, is an illustration. Who can execrate Parsa for helping us to grasp just how many facinerous people there were in the Continental Congress! His project ought to award him a singular feather, large and beautifully colored, for his filmmaking chapeau!

Yet something has gone awry.

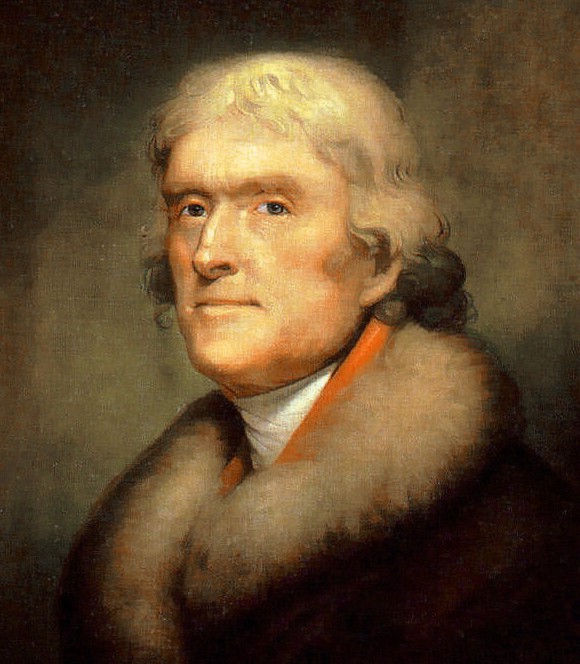

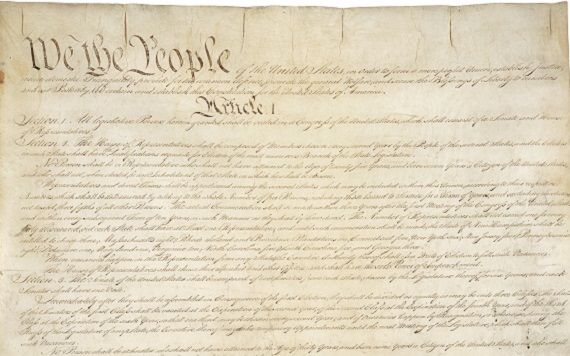

We are in an enviable position to discuss the evils of slavery today just because of the efforts of the Founding Fathers—consider Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence and its global influence over the centuries—many of whom owned slaves. All knew that the institution of slavery would collapse in time of its own weight. All knew, however, that the time was not kairotic to push for eradication of the institution at the time of Jefferson’s Declaration—hence, his lengthy peroration on the evils of slavery was excised from his draft by members of the Congress. Southern states then were too heavily invested in the labor of slaves, and with war declared against England, it was a poor time to discuss the morality of slavery.

Are we any better off today in our discussions on slavery?

There are many incommodious truths concerning American slavery, many of which are glossed over or ignored in these politically correct times. Black slaves were captured and sold by West African kings, shipped to England, and then brought, among other places, to the Northern ports of this country, where they were then sold to Southerners, in need of labor. With the trade of slaves, there are also many seldom-told, sad-but-true stories: e.g., of African kings who thrived monetarily and through large increase in celebrity on selling African Blacks, captured in wars to gather slaves, to slave-traders (e.g., Kings Tegbesu and Gezo); of free Blacks owning slaves for ease of living and elevation of social status (e.g., Madame Elizabeth Langley of Lynchburg); of numerous white slaves (e.g., two are listed by Dr. George Cabell as part of his luxury tax for the War of 1812 at his Point of Honor estate in Lynchburg); and of slaves freed by sympathetic owners who would come to find life as a free black person worse than being a slave (e.g., perhaps James Hemings, who bought his freedom from Jefferson and soon committed suicide), inter alia.

My point is this: The moral atrocities of slavery are today amply covered, but only the moral atrocities of slavery are today amply covered. Due to political correctness, we craft the sort of history we wish to hear—and it is exclusively a history of Whites hating Blacks—and we ignore incommodious details. Is that the sort of selective history that we want the next generations to read? Shall we just blot out the faces of those whom we deem to be hypocrites instead of trying to understand why they behaved and thought as they did? Yet we, who are quick to criticize them, would not have behaved and thought any differently had we been in their places. Of that, I am sure.

Then there is the yarn of the pious anti-slavery North and the wicked pro-slavery South.

Thomas Jefferson knew well the hypocrisy of Northern politicians when they made slavery the big issue behind the Missouri crisis. He writes in a letter to Albert Gallatin (26 Dec. 1820):

nothing has ever presented so threatening an aspect as what is called the Missouri question. the Federalists compleatly put down, and despairing of ever rising again under the old division of whig and tory, devised a new one, of slave-holding, & non-slave-holding states, which, while it had a semblance of being Moral, was at the same time Geographical, and calculated to give them ascendancy by debauching their old opponents to a coalition with them. Moral the question certainly is not, because the removal of slaves from one state to another, no more than their removal from one county to another, would never make a slave of one human being who would not be so without it. indeed if there were any morality in the question, it is on the other side; because by spreading them over a larger surface, their happiness would be increased, & the burthen of their future liberation lightened by bringing a greater number of shoulders under it. however it served to throw dust into the eyes of the people and to fanaticise them, while to the knowing ones it gave a geographical and preponderant line of the Patomac and Ohio, throwing 14. states to the North and East, & 10. to the South & West.

The issue, Jefferson notes and he is certainly correct, is one of political clout. As a result of Jefferson’s, Madison’s, and Monroe’s presidencies, the Federalists have shrunk to virtual nonexistence, and so they have rallied around a new issue, slavery, and they aim to fatten their lean bodies by making themselves true champions of its eradication. Eradication of slavery would cripple the Southern economy and bring the North to political prominence.

Jefferson continues:

with these [Federalists] therefore it is merely a question of power: but with this geographical minority it is a question of existence. for if Congress once goes out of the Constitution to arrogate a right of regulating the condition of the inhabitants of the states, it’s majority may, and probably will next declare that the condition of all men within the US. shall be that of freedom. in which case all the whites South of the Patomak and Ohio must evacuate their states; and most fortunate those who can do it first. and so far this crisis seems to be advancing.

Jefferson was right to note that the issue was not slavery, but political clout. Rallying Northern states around the issue of slavery during the Missouri issue—the Northern economy did not need the labor of slaves as did the Southern economy, though Northern mills thrived on Southern cotton—was a way of resuscitating moribund Federalist political power. Northern political clout by rallying around slavery, for instance, is evident years later in the 1860 presidential election, in which Abraham Lincoln handily won the popular vote and overwhelmingly won the electoral vote without carrying even one Southern state. Jefferson was aware of the increasingly large populations in the Northern and Eastern states and unevenness of representation in the House of Representatives. His concern was that Southern interests—and the South was strongly states’ rights—would be swept under large Northern rugs. In short, Northerners were paying mouth honor to the issue of the evils of slavery in order to militate against Southern political interests and bolster their own. Jefferson’s well-founded fear was that by forcing the issue of eradication of slavery at the time of the Missouri crisis would have left the South with no options but secession, or war.

Jefferson is today roundly criticized, and I believe unfairly, for racial hypocrisy: He argued for racial equality, yet he likely thought that Blacks were deficient in imagination, beauty, and intellect—in such things, he differed little from most others of his day—and did little to free his slaves.

Such things are true, yet this question redounds: Where would Jefferson’s slaves, if freed, have gone to ensure that their life, as freed men, would be better?

Too little has been written about persons of color, once freed, who had found “freedom” insufferable. Jefferson certainly knew that—the suicide of James Hemings after his freedom was likely a large blow to him—and it was certainly one of the reasons that he freed so few slaves. They had to be skilled and readied for emancipation, and being light-skinned would have been an additional asset. Moreover, most of Jefferson’s slaves loved or respected him, and would probably have balked at the opportunity to be freed, lest they soon found themselves in a worse condition. It just might be that humans, following Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents, find security much more attractive than freedom.

Jefferson was more far-seeing than hypocritical on the issue of slavery. Few scholars seldom record his prescience when he says in Query XIV of Notes on Virginia of certain political objections to freeing Blacks. He begins with a question, “Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expence of supplying by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave?” He answers: “Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions, which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.”

That is a powerful passage. Those scholars who do reference the query seldom take notice that Jefferson there blames Whites, on account of their prejudices, and that he underscores the recollections of injuries, over many decades, suffered by Blacks. Whites’ prejudices and the painful recollections of Blacks make it, for Jefferson, almost inevitable that there will be racial wars if Blacks are freed.

Yet scholars seldom acknowledge Jefferson’s prescience because it cannot today be done. It is today politically correct to bury Jefferson, not to praise him. After all, he did, as Parsa notes by blotting out Jefferson’s face, own slaves.

Nevertheless, it has been over 150 years since Blacks were formally emancipated and around 250 years since Jefferson penned his sentiments, and the tension, and hatred, between the races, in many pockets of the country, seems to be as strong as ever.

We ought to be chary about blotting out the faces of past prominent figures and assume a position of moral superior. It neither is nor ought to be the aim of historians to censure historical personages. In cases where venality is obvious, descriptive details of a person’s actions and course of life—Alexander of Macedon and Napoleon are prime illustrations—will speak on behalf of the venality. In cases where the venality is not so obvious, scholarly discretion is warranted.

We might exercise more scholarly caution if we remembered this inconvenient truth: Rogues and charlatans most readily see roguery and charlatanry in others.

Thus, we ought to suspend moral judgment, as it just might be the case that some morally superior person in the decades to come might find blotting out our face to be an agreeable way of passing the time.

In the 7th paragraph from the end is there an edit needed? Seems wrong to say “few scholars seldom….” Is that a double negative, intentional?