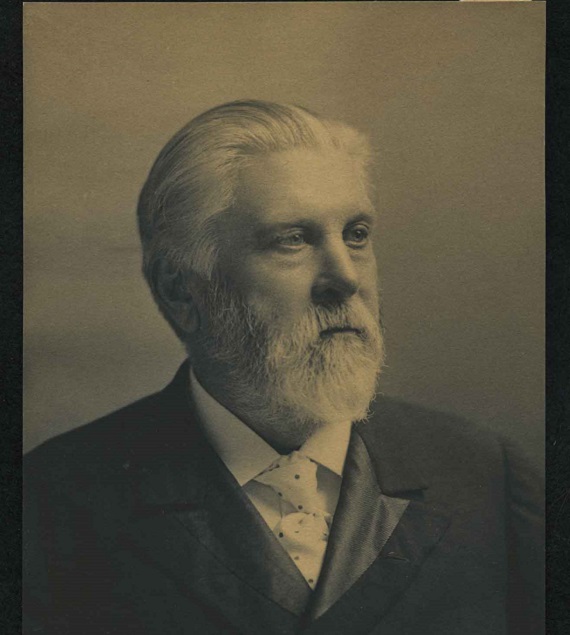

John Chodes, Destroying the Republic: Jabez Curry and the Re-Education of the Old South. New York: Algora Publishing. 332 pp. $29.95 (quality paperback)

Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry of Alabama (1825–1903) was one of those fairly numerous 19th century Americans whose lives of astounding talent and energy put to shame the diminished leaders of the U.S. in the 21st century. Or rather would put them to shame if they had sufficient intelligence to distinguish their own inferior quality.

Learned and articulate, a lawyer, Baptist minister, college president, diplomat, member of the U.S. and Confederate congresses, Confederate combat officer, prolific and eloquent writer and orator, Curry was a significant public figure from the 1850s to the 1890s. (Put beside Curry or any of his contemporary peers, George W. Bush and Teddy Kennedy look like dull-witted adolescents.)

Mr. Chodes’s libertarian work on Curry’s career is a rich source of understanding of many aspects of 19th century American history. Having the good fortune not to be a “professional historian,” the author is able to see many things that the professionals have been socialized not to see. Fine as Mr. Chodes’s work is, however, it leaves me with a serious unanswered question. Shall I put it on the shelf with the DiLorenzo school of revisionist Civil War history? Or with works on the evils of Reconstruction? Or beside John Taylor Gatto’s Underground History Of American Education?

The chapter on “Reconstruction as Re-Education” is alone worth the price of the book. The Marxist class/conflict perspective, with a Gramscian twist, is now “mainstream” American history. All of American history has been distorted but no part more so than Reconstruction. Chodes shows that Reconstruction was more than a horror of military domination and economic exploitation. It was also a program of ideological and ethnic cleansing which continues to damage the American people in our own time. The many observers who seem to think that militarism and abuse of citizens is an innovation of the Bush administration have evidently not familiarized themselves with President Grant and the Reconstruction Congress.

Those who think that federal control of education was an invention of the Democrats and the Great Society have a lot to learn. It was the Republican President Hayes who declared education to be one of “the rights of man” to be supported by taxation and devoted to inculcating national unity. His successor, the Republican Garfield, devoted his first message to Congress to promotion of federal funding of public schools. “It is the voice of the children of the land,” declaimed Garfield, “asking us to give them all the blessings of our civilization.”

Legislation to answer the voice of the children was pushed in Congress by New England Republicans in 1882–83 and barely failed of passage. This was seven years after the formal end of Reconstruction. The strongest public rationale, but not the only motive, was to alleviate the illiteracy of the freed people of the South. This rationale, like that of all the Reconstruction measures, was based on calculated misrepresentation of conditions in the South. Great strides were being made in education in the Southern states, which were devoting more of their resources to the effort, in proportion to their wealth, than Northern states (as they have ever since). Even greater progress would have been made if the funds Southerners had appropriated out of their poverty in the first years after the war had not been systematically stolen by the same Republicans who decried the South’s ignorance. The National Bureau of Education, which from the 1880s was the chief instrument for carrotting and sticking American public schools into conformity with elitist plans, originated lock, stock, barrel, and personnel out of the Reconstruction Freedmen’s Bureau which had been to a large extent the irresponsible and coercive de facto government of the South.

The Republican proponents of federal education were clear about their desire to create a system on the statist, militarized models of Europe. No American educational ideas that preceded Horace Mann’s Prussian/Massachusetts school system were to be considered. Black voters had to be subsidized enough to vote Republican and to be content where they were, else they might migrate to the North and West. They had to be kept in the South, which was the main theme of Northern politics throughout the 19th century, an even stronger imperative than the desire to loot the productive Southern economy. Further, federally-controlled, “free,” universal, compulsory public schools were needed to control the immigrant masses of the northeast.

Behind it all, as Chodes shows, was a commanding assumption and necessity. As one New England promoter of federal education put it, “But for ignorance among the nominally free, there would have been no rebellion.” If Southerners had not been too ignorant to understand the benefits of patterning themselves after New Englanders, there would have been no bloody war. To prevent decentralization in the future, Southern whites had to be cleansed of their “ignorance,” that is of their un-New England thoughts. Federal public schooling was also needed to confront the “hordes coming from beyond the great oceans.” It had nothing to do with learning and everything to do with control of the population by their betters.

While the Republican plan for centralized and regimented public schools failed in the House of Representatives and had to wait some years before full implementation, all was not lost. The Morrill Act of the Lincoln administration took a long step toward federalizing higher education. The Lincolnian Department of Agriculture was able to work itself into the public schools by “extension” agents. The philosophy of education that governed the department, as Chodes conclusively shows, was behaviorist, fully anticipating the psychological manipulation of children by the self-appointed wise and good that was the essence of Deweyism and is now entrenched national policy. Again, the barely vanquished Southern demon spurred on the effort. Southern devotion to such immaterial, reactionary ideals as courage and honour had been responsible for rebellion. Future generations must be made into pragmatic American materialists suitable for labour and production.

If the elite wise and good could not get sweeping federal legislation to further the control and conformity of education, they had another string to their bow. This is where the sad paradox of Jabez Curry comes in. This eloquent and indefatigable defender of the South and of the constitutional principles of the old republic spent the last two decades of his long life as head of the Peabody Educational Fund, a northern charity with several millions of dollars to be devoted to the advancement of education in the South. The work of Curry and the other elitists who controlled the great instruments of charitable wealth was devoted entirely to fostering a certain kind of education—universal, compulsory, “free,” tax-supported graded public schooling. Besides relentless propaganda, their chief tool was the “matching” grant. Substantial amounts of cash were available to local and state authorities who would match the gifts out of tax-paid funds.

Thus were established, step by step, universal, compulsory state school systems, whose content and direction were essentially provided by Deweyite “normal schools.” It should be noted that indirect control of public policy by institutions of great wealth (accumulated before the income tax) is now a norm of American government. Such leveraging of wealth into elitist political dictation is unconstitutional and undemocratic, but the Rockefeller, Carnegie, Ford, etc. foundations dictated much of the domestic social legislation and foreign policy of the United States in the 20th century. Their power is nearly as great and even more irresponsible than that of the Supreme Court or the media. And it is never mentioned. George Wallace is the only public figure, to my knowledge, has ever called attention to this unelected power over the people of the United States.

The governing board of the Peabody endowment, supposedly a private charity, met in the White House and also counted the sitting President as a member. The nature of the whole enterprise is perhaps revealed in the fact that Grant, though a civilian, attended the meetings in full military regalia. Part of Peabody’s fortune had been accumulated through the manipulation of fraudulent bonds of Southern carpetbagger state legislatures. J.P. Morgan was the manager of the trust. How did the ex-Confederate Curry become an instrument for the undoing of his own principles and his own people? For doing the bidding of rich inveterate South-haters? It was not simply a case of a defeated Confederate making the best of a bad situation. Education is, of course, a good thing. The South was poor and needed money for education. But why did a man like Curry buy the whole hog – not just education but universal, compulsory, “free,” tax-supported schooling on a model dictated by the relentless Bostonian enemies of his blood?

Other articulate Southerners saw what was going on. Possibly Jabez Curry saw it also but refused to acknowledge the truth. John Chodes shows us in revealing context and detail what happened. Why is perhaps one of those mysteries buried deep in the human heart.

It has long been an accepted article of faith among Americans that education is a good thing. That, indeed, it is a necessity for a free and self-governing people. But when and by whom was it determined that this desirable thing was to be universal, compulsory in attendance and tax support, “free,” and devoted to inculcating government-coerced conformity? Destroying the Republic provides much of the answer to this vital question.

January 30, 2006

Copyright © 2006 LewRockwell.com. Reprinted by permission.