At the University of Virginia, Room No.13 on the fabled Lawn is reserved as a permanent shrine to Edgar Allan Poe, who reportedly lodged in the room during his brief time on campus (or “the grounds,” as we say). One wonders what Poe, though a proud Virginian, would think about this honor — he was not terribly happy with his time at “Mr. Jefferson’s University,” complaining that his economic and familial poverty isolated him from his fellow students. He later wrote:

I could associate with no students, except those who were in a similar situation with myself – altho’ from different causes – They from drunkenness and extravagance – I, because it was my crime to have no one on Earth who cared for me, or loved me.

That bit about drunkenness is a tad ironic, given that Poe later struggled with drink (though his story “The Black Cat” is an indictment of alcoholism, and a few months before his death he became a vocal member of the temperance movement). Yet I suppose it’s also in keeping with Poe’s literary corpus, which immerses itself in paradoxes, tragedy, and, of course, the morbid.

It would be fair to say that in many respects, Poe’s writings, filled with the violent and grotesque, epitomizes the original Southern Gothic. The Gothic part isn’t hard to prove. Perhaps his most famous short-story, “The Tell-Tale Heart,” is about a man driven mad by the sound of the still-beating heart of the elderly man he killed and buried under the floorboards. In “The Cask of Amontillado,” a dishonored Italian gets his revenge on an enemy who had publicly insulted him. Luring his drunken foe deep into his wine cellar, the man chains up his adversary and then permanently traps him behind a wall of bricks.

And though certainly many of his stories take place in Italy, France, or elsewhere in Europe, the South is also a frequent setting. “A Tale of the Ragged Mountains,” a ghoulish and somewhat absurd story about a haunted neuralgic individual who dies after wandering in the Blue Ridge Mountains outside Charlottesville. “The Gold-Bug,” a story about cryptography and buried treasure that influenced Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, is set on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, where Poe briefly served while in the U.S. Army.

Moreover, many of the themes now associated with Southern Gothic are prevalent in Poe. Like Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! and The Sound and The Fury, Poe told stories of noble and illustrious families who suffer decay and eventually collapse in on themselves. In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” an isolated brother descending into madness entombs his sister whom he presumes is dead; during a storm, her sudden, bloody appearance shocks her brother to death. She too expires, and the narrator escapes the mansion just before it collapses into an adjacent lake. In The Black Cat, a man driven insane by his alcoholism accidentally kills his long suffering wife and, until he is caught, hides her body in the basement (one sees a recurring theme, no?).

And, like Flannery O’Connor, Poe at times seems to be shocking his readers out of their false beliefs and self-righteousness. “Never Bet the Devil Your Head,” is a not-so-subtle indictment of transcendentalism, which had become popular among many of the Northern intelligentsia. “The Mask of the Red Death,” in turn, warns against the thoughtless indulgences of the elite: the nobility who hide themselves away in an abbey to avoid a plague — and even have the audacity to hold a masquerade ball while peasants die outside — eventually succumb to the sickness.

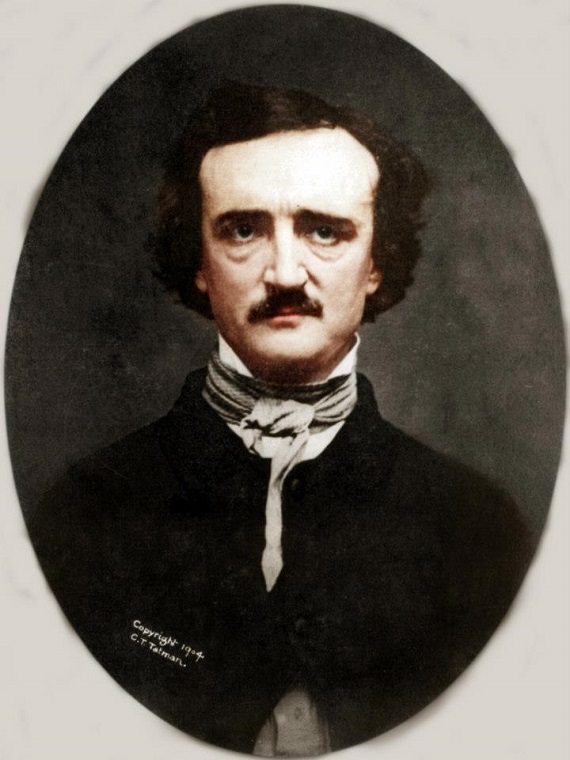

Of course, Poe was also, in a word, Southern. Though born in Massachusetts to actors employed in the Boston Theatre, he was informally adopted by Mr. and Mrs. John Allan of Richmond after his father abandoned the family and his mother died. “I am a Virginian,” he once declared, and “the distinguishing features of Virginian character at present-features of a marked nature-not elsewhere to be met with in America-and evidently akin to that chivalry which denoted the Cavalier-can be in no manner so well accounted for as by considering them the debris of a devoted loyalty.”

Apart from his brief time at the University of Virginia, he also lived in Richmond where he worked for the Southern Literary Messenger. Much of his career was also spent in Maryland, where he died in 1849, two years after the death of his wife Virginia from tuberculosis.

Perhaps his Southern character is best manifested in his rhetorical war of words over the snobbish dominance of the Northern literati, a topic well-covered by Harry Lee Poe at Abbeville. Poe reprimanded poetry editor Rufus Griswold for his “prepossession, evidently unperceived by himself, for the writers of New England.” Poe later sarcastically mourned that Southern writers did not have “the good fortune to be born in the North.”

Poe elsewhere cited William Gilmore Simms as a writer whose “genius would have been rendered immediately manifest to his countrymen, but unhappily (perhaps) he was a Southerner….” He later labeled prominent Northern writer James Russell Lowell “one of the most rabid of the Abolition fanatics” and advised that “no Southerner who does not wish to be insulted, and at the same time revolted by a bigotry the most obstinately blind and deaf, should ever touch a volume” by Lowell.

Poe was, in many respects, a true genius, bequeathing to future generations not only a new genre of the macabre gothic, but a genre of detective fiction — visible in “the Murders in the Rue Morgue” and “The Purloined Letter” — that were obvious inspirations for future writers like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. That Poe was not more beloved in his own time is due certainly in part to his tendency to employ his literary craft to trenchantly criticize some of the greatest writers of his day, but also, as he himself believed, because of his Southern identity. Multiple times he referred to his Yankee opponents as “bigots” towards the Southern people.

That too reflects a certain paradoxical irony, since it was those same Northern detractors who believed Poe and his Southern kinsman to be bigots because of slavery (though Poe was also ahead of his time in his sympathetic portrayals of blacks). As one of Poe’s detractors, Rufus Griswold wrote: “EDGAR ALLAN POE is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it.” There is a certain poetic fittingness even to that ignominious obituary: from birth until death, he was poor Poe.

I love Poe, thanks to a very talented actor from Oregon, Alastair Morley Jacques, who visited Idaho to do an Edgar Allan Poe performance for our community library. I had not read many of Poe’s works, but we were in a happy Halloween mood and were prepared to enjoy the spectacle. Jacques stayed in character the whole night, flawlessly reciting “The Cask of Amontillado” and saving “The Raven” for last. By the end of “The Raven”, I was in tears. It was an unexpected and unforgettable experience and, needless to say, inspired me to read many more of Poe’s works. Thank you for this article!