The following is an excerpt from the forthcoming book, The Last Words, The Farewell Addresses of Union and Confederate Commanders to Their Men at the End of the War Between the States (Charleston Athenaeum Press, 2021) by Michael R. Bradley and is published here by permission.

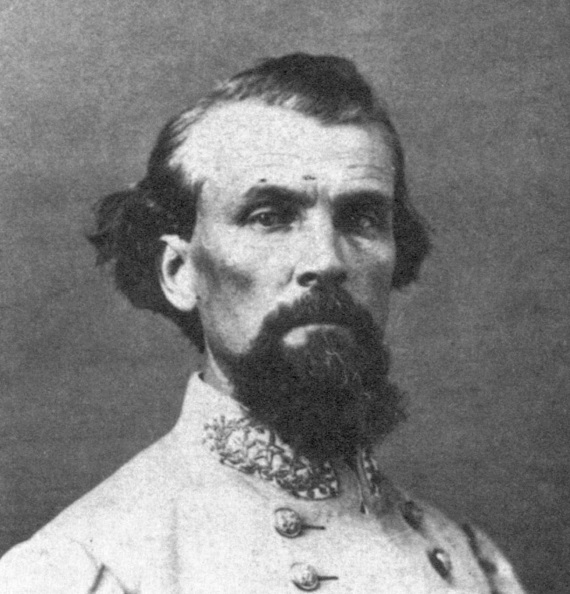

The Farewell Address of Nathan Bedford Forrest

to Forrest’s Cavalry Corps, May 9, 1865

Soldiers:

By an agreement made between Liet.-Gen. Taylor, commanding the Department of Alabama. Mississippi, and East Louisiana, and Major-Gen. Canby, commanding United States forces, the troops of this department have been surrendered.

I do not think it proper or necessary at this time to refer to causes which have reduced us to this extremity; nor is it now a matter of material consequence to us how such results were brought about. That we are BEATEN is a self-evident fact, and any further resistance on our part would justly be regarded as the very height of folly and rashness.

The armies of Generals LEE and JOHNSTON having surrendered. You are the last of all the troops of the Confederate States Army east of the Mississippi River to lay down your arms.

The Cause for which you have so long and so manfully struggled, and for which you have braved dangers, endured privations, and sufferings, and made so many sacrifices, is today hopeless. The government which we sought to establish and perpetuate, is at an end. Reason dictates and humanity demands that no more blood be shed. Fully realizing and feeling that such is the case, it is your duty and mine to lay down our arms — submit to the “powers that be” — and to aid in restoring peace and establishing law and order throughout the land.

The terms upon which you were surrendered are favorable, and should be satisfactory and acceptable to all. They manifest a spirit of magnanimity and liberality, on the part of the Federal authorities, which should be met, on our part, by a faithful compliance with all the stipulations and conditions therein expressed. As your Commander, I sincerely hope that every officer and soldier of my command will cheerfully obey the orders given, and carry out in good faith all the terms of the cartel.

Those who neglect the terms and refuse to be paroled, may assuredly expect, when arrested, to be sent North and imprisoned. Let those who are absent from their commands, from whatever cause, report at once to this place, or to Jackson, Miss.; or, if too remote from either, to the nearest United States post or garrison, for parole.

Civil war, such as you have just passed through naturally engenders feelings of animosity, hatred, and revenge. It is our duty to divest ourselves of all such feelings; and as far as it is in our power to do so, to cultivate friendly feelings towards those with whom we have so long contended, and heretofore so widely, but honestly, differed. Neighborhood feuds, personal animosities, and private differences should be blotted out; and, when you return home, a manly, straightforward course of conduct will secure the respect of your enemies. Whatever your responsibilities may be to Government, to society, or to individuals meet them like men.

The attempt made to establish a separate and independent Confederation has failed; but the consciousness of having done your duty faithfully, and to the end, will, in some measure, repay for the hardships you have undergone.

In bidding you farewell, rest assured that you carry with you my best wishes for your future welfare and happiness. Without, in any way, referring to the merits of the Cause in which we have been engaged, your courage and determination, as exhibited on many hard-fought fields, has elicited the respect and admiration of friend and foe. And I now cheerfully and gratefully acknowledge my indebtedness to the officers and men of my command whose zeal, fidelity and unflinching bravery have been the great source of my past success in arms.

I have never, on the field of battle, sent you where I was unwilling to go myself; nor would I now advise you to a course which I felt myself unwilling to pursue. You have been good soldiers, you can be good citizens. Obey the laws, preserve your honor, and the Government to which you have surrendered can afford to be, and will be, magnanimous.

N.B. Forrest, Lieut.-General

Headquarters, Forrest’s Cavalry Corps

Gainesville, Alabama

May 9, 1865

General Orders No. 22[1]

Nathan Bedford Forrest is the most controversial, and the most misrepresented, general officer of the entire war. He is the man liberal historians love to hate and the man Civil War buffs adore. Forrest is celebrated for his military genius and his intuitive grasp of psychological warfare (keep the scare on ’em) and damned for his supposed approval of a massacre of African American and white Tennessee Unionists at Fort Pillow and for his presumptive post-war leadership of the Ku Klux Klan. William T. Sherman said, in 1864, “there will never be peace in Tennessee until Forrest is dead.” Since controversy and argument still swirl around Forrest it appears he is not deceased!

Forrest grew up on a small farm in Bedford County, Tennessee (his birthplace is now in Marshal County thanks to a redrawing of boundaries) and became “the man of the family” in his early teens when his father died. Later he took the family to Mississippi where he became a successful farmer, businessman, and political leader. He moved to Memphis, engaged in the slave trade, and was elected alderman. By 1860, still in his thirties, he was worth over a million dollars.

Forrest enlisted as a private, was made a lieutenant colonel almost immediately and was instructed to raise a regiment of cavalry. As head of a cavalry force he rose quickly through the ranks to become a lieutenant general before the end of the war. Forrest also established a reputation for hard fighting, beginning with his first encounter of any importance at Sacramento, Kentucky and continuing to his last battle at Selma, Alabama. He also perfected the technique of striking deep behind the Union front line to disrupt lines of supply. The first attempt by Forrest at such raiding came in July 1862 at Murfreesboro, Tennessee on his forty-first birthday. He repeated the tactic in December 1862 by raiding for two weeks into West Tennessee, thoroughly destroying the Mobile & Ohio Railroad which brought supplies to the army of Ulysses S. Grant. By 1864 Forrest had been given an independent command in Mississippi and West Tennessee and there he won some of his most brilliant victories such as Brice’s Cross Roads. Two other raids into Middle Tennessee and West Tennessee in 1864 cemented his grasp of raiding.

Forrest spent most of his military career doing traditional cavalry service, scouting and screening the infantry force of the Army of Tennessee. It was in this traditional capacity that he served at Fort Donelson, at Shiloh, and throughout 1863 during the Tullahoma and Chickamauga campaigns.

By the end of the war Forrest was the most feared opponent the Union had in the west and the most celebrated leader in the Confederate ranks. His campaigns are still studied today as early examples of mobile warfare.

Fort Pillow, April 9, 1864, casts a dark shadow over the memory of Forrest. Something happened there which has been exploited but never explained. After an all-day engagement Confederate forces got close enough to the fortifications at Fort Pillow to capture them by storm, doing so only after the Union commander had refused to surrender. In the ensuing chaos of a position captured by direct assault some Union soldiers were killed in a manner which violated the rules of war. The crucial questions of how many such deaths occurred and who is responsible have never been answered, though Forrest, as commanding officer, bears responsibility for the conduct of his troops.

The Fort Pillow affair was immediately exploited by the North. A congressional committee investigated the matter and published a report of which 40,000 copies were distributed, in which survivors gave graphic reports of men being shot after surrendering. One very obvious problem is that none of these witnesses gave the name of a single person who they saw killed. The men of these units had served together for more than a year, yet no-one recognized a friend, mess mate, or non-commissioned officer who was killed unlawfully. The more serious problem is that the Congressional Report has all the markings of a propaganda piece. The Union cause, militarily and politically, was at a low ebb. The Confederates had taken serious blows in 1863 but they still appeared full of fight. Recruitment in the North was difficult and very large bounties were being offered to lure recruits. The Democratic Party, with its call for peace, appeared to be in good position for the 1864 elections at all levels—state, congressional, and presidential. Something was needed to arouse public opinion in support of the war. Fort Pillow was used to provide that stimulus.

Post-war, the name of Bedford Forrest came to be associated with the Ku Klux Klan. The assertion that Forrest was head of the Klan has been repeated in so many books as to be beyond counting. The problem with this assertion is that no historian has ever produced any primary source document which proves Forrest held that position. Writers of secondary sources cite each other but none cite a document from the 1860—70’s to prove their case. In short, there is no valid historical evidence to support the claim that Forrest was head of the Klan.

Eric Foner is considered by many to be the leading contemporary historian of the Reconstruction Era. His book, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, discusses the Klan in great detail over a number of chapters. The name of Bedford Forrest is never mentioned. A growing number of academic historians admit that there is no evidence linking Forrest to the Klan, yet still the folklore is repeated whenever the name of Forrest is mentioned.[2]

The historical fact is that a congressional investigating committee cleared Forrest of any involvement with the Klan and commended him for his opposition to the group. Forrest also became an advocate for African Americans exercising the right to vote. Historians who condemn Forrest for his supposed affiliation with the Klan either ignore these facts or make great efforts to dismiss them but in doing so they violate the duty of an historian to deal with facts and not to substitute personal opinions or folklore for primary sources.

Forrest was a fierce fighter. His force held out until May 9, 1865, a month after the fighting had ended in Virginia and several days after it had ended in North Carolina. Forrest accepted the inevitable with good grace and advised his men to do likewise. The farewell address he issued to his command at Gainesville, Alabama is a model of calmness and reconciliation.

There were no U.S. forces present to accept the surrender of Forrest’s command. On the morning of their departure the men fell in for roll call and Forrest’s final order was read aloud. The men then marched by their own ordinance sergeants and turned in their weapons, the artillery was parked in a grove of trees, and the men then reported to their regimental adjutant to received previously printed and signed paroles. Then they went home.

What does Forrest’s final address tell us about his ideas concerning the cause of the war? The order states that, for Forrest, the causes of the war were irrelevant but that the result of the war was obvious, the South had lost and the Confederacy was no more. The only thing for sensible people to do was accept the results and get on with their lives. This statement reflects the same pragmatic attitude with which he had fought during the war. It should be noted that Forrest had opposed secession and had voted against it in February 1861 when Tennessee took its first vote on the issue. Forrest stood by the Union as long as the Union stood by the existing laws. Once respect for law was abandoned Forrest moved to protect his home.

Forrest’s Escort Company and Staff formed an association even before the United Confederate Veterans were formed and they regularly read aloud the Farewell Address. The sound advice it contained stood them in good stead during the hard economic times that followed the war. The words do much to disprove the common public impression that Forrest was a monster.

[1] Thomas Jordan and J.P. Pryor, The Campaigns of General Nathan Bedford Forrest and of Forrest’s Cavalry (New York: Da Capo Press, 1996), 680-82. Originally published 1886.

[2] See Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (New York: Harper Perennial, 2014). Originally published, 1988.

That we are beaten is a self-evident fact!

A bit off topic, on defeat and costs:

With all that is going on concerning Afghanistan withdrawal and reading this article, I realized that while Lincoln proved Madison (Federalist 46) wrong, the Taliban has shown Madison was correct (in a way). A federal army formed with the greatest resources available was repelled by (arguably) an inferior army, armed with old AK47s. Rifles and resolve can lead to victory.

Thank you for writing this article and I’ll certainly put that book on the to buy list.

As usual, gacta mean little to the “modern, learned people” of our day. Forrest, like many others were compelled by the misdeeds of the federal government to respond in a way that went against their usual behavior. Oh to have men of principle in our land today!