From the 2011 Abbeville Institute Summer School.

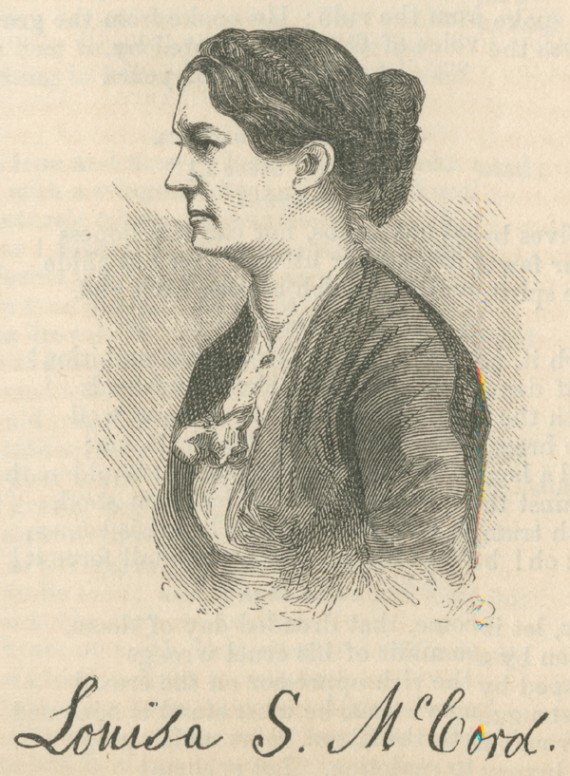

The name of the lady I’m introducing today, the Southern intellectual Louisa Susanna Cheves McCord, or as she’s usually called, Louisa S. McCord, is generally not well known today. In the antebellum era she was the author of numerous essays on political economy and social issues. Her other writings included poetry, reviews, and a blank verse drama entitled Caius Gracchus. She also translated a book written by French political economist Frédéric Bastiat which was published in 1848 as Sophisms of the Protective Policy.[1] Although Louisa McCord was written about here and there in the 19th and 20th centuries, it’s only relatively recently that she’s begun to receive her due recognition as one of the most significant thinkers of the antebellum South. Most importantly, in 1995 and 1996, her writings were collected and published in two volumes. The first volume contained her political and social essays, the second volume her poetry, drama, biographical writings, and letters.[2] Both books were edited by Richard C. Lounsbury, a classical scholar.[3] A two-volume anthology published in 1993 entitled The American Intellectual Tradition put Louisa McCord in the company of Jonathan Edwards, Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, John C. Calhoun, and other luminaries of antebellum America.[4] The editors made the claim for her that she was the most intellectually influential female author in the Old South and the only woman in antebellum America to write extensively about political economy and social theory.

Louisa S. McCord (née Cheves) was born in Charleston, South Carolina, on December 3rd, 1810. Her father was Langdon Cheves, an attorney and planter from Abbeville who achieved national eminence as a statesman, jurist, and financier. He was a U.S. Representative and served as Speaker of the House from 1814 until his retirement from Congress in 1815. During his tenure as Speaker, one of his most important accomplishments was to defeat the re-chartering of the Bank of the United States. In 1816, after Langdon Cheves retired from Congress, the Bank was re-chartered and in 1819 he accepted the urgent request of his friends to take over the Bank and become its director. In doing so, Cheves gave up the opportunity to serve on the Supreme Court, to which President Monroe had appointed him. Thanks to three years of mismanagement, the Bank was in a deplorable condition, its liabilities exceeding its assets. John Quincy Adams recorded in his diary at the time that he feared a national convulsion would result from its failure. By 1822, however, Cheves’s policies had succeeded in restoring the Bank’s credit. In politics, Langdon Cheves was an opponent of nullification, favouring secession as the solution for State grievances if necessary, and he was a delegate to the 1850 Nashville Convention. Until the age of ten, Louisa Cheves received the usual education given to girls of her social class, but when it was discovered that she had an aptitude and a passion for mathematics, her father saw to it that she received the same instruction as her brothers. In a thesis published in 1919, Jesse M. Frazier described another dimension of Louisa’s formative years. Frazier wrote: “In her father’s study and at his table she heard the discourse of his contemporaries, Webster, Calhoun, Clay, and their associates. Political economy was the gospel of their theories. Statecraft was their game. The young girl hearing them express their theories, seeing them play their game, learned to think deeply on political issues. She noted the hearts and minds of great men at work.” Along the same lines, Louisa’s cousin, William Porcher Miles, wrote of her:

“The bent of her genius was rather for matters of state policy and political economy, rather than for subjects commonly called general literature. Now, was this strange when we consider the long public life of her father, during which she was habitually thrown with the leading statesmen of the country, and so often her discussed the then-absorbing topics of States’ rights, free trade, tariffs, and the banks?”

In 1840, Louisa Cheves married David James McCord of St Matthew’s Parish. He was a prominent lawyer and editor, the author of numerous legal works, a state legislator, and, unlike Louisa’s father, a devoted advocate of the doctrine of nullification. The fifteen years of Louisa’s marriage to David J. McCord before his death in 1855 were the richest and busiest in terms of her writing. During this period, she was published in such journals as The Southern Quarterly Review, DeBow’s Review, the Southern Literary Gazette, and the Southern Literary Messenger. Her drama, Caius Gracchus, a book of poetry entitled My Dreams, and her translation of Bastiat’s book were all published under her name, but her political and social essays and reviews were usually published anonymously, though some were signed with her initials, “L.S.M.” The McCords divided their time between Lang Syne own plantation in what is now Calhoun County and their home in Columbia. Three children were born to the couple: A son, Langdon Cheves McCord, and two daughters, Hannah and Louisa Rebecca. During the family’s winters in the country, Mrs. McCord mainly made a daily round of supervision on horseback as the plantation mistress. One of her daughters wrote of her: “She was one of the many Southern women who took their responsibilities very seriously and devoted time and thought to the welfare and happiness of her servants as well as to the prosperity of her home.” A foreign visitor to Lang Syne, Dr. E.D. Worthington of Canada, wrote of Mrs. McCord in a letter: “If any of the Negroes were sick, she had the medicine chest and dispensed liberally.” Dr. Worthington went on to describe how she, with his help, cured lameness in a servant boy named Ben, noting how tenderly the child was cared for.

As a thinker, Louisa McCord was conservative and classical. She detested abolitionists, feminists, and socialists. According to the historian Robert Duncan Bass, Louisa McCord’s translation of Frederic Bastiat’s book in 1848 influenced all her subsequent political thinking. Bass wrote: “Her essays, polemic, satiric and always clear and coherent were conservative, pro-slavery and pro southern. Her ideal was a South with a Southern culture, classic learning, with economic independence based on slavery and cotton. In her polemical writings, Louisa McCord dealt chiefly with three subjects: slavery, women, and political economy. The subject she wrote about most extensively was slavery, and she wrote to defend it. She regarded slavery – at least as it was practiced in the American South – as a benevolent institution beneficial to both master and slave. She believed, like most Americans of her time, that there was an inequality between the races, and like Abraham Lincoln, she assigned the superior position to the white race.[5] In her essay entitled “Diversity of the Races,” published in The Southern Quarterly Review in 1851, she appealed to current scientific thought on the subject, quoting from Dr. Samuel George Morton of Philadelphia, his protege, Louis Agassiz of Harvard, and other men of science. Louis Agassiz, one of the most famous scientists in the world at the time, theorized that the races came from separate origins, that is separate creations, and were endowed with unequal attributes. This theory was known as polygenism or polygenesis. It might be less surprising to find such views being advanced by a Southern woman of the mid-19th century when we consider that, according to the scientist Joseph LeConte of South Carolina, Louisa McCord’s brother, Langdon Cheves, had articulated the idea of natural selection before Charles Darwin’s famous work on that subject was published. In his autobiography, Joseph LeConte wrote of a conversation he had with Langdon Cheves concerning the origin of species. Cheves, he recalled, advanced the idea, “That intermediate links would be killed off in the struggle for life as less suited to the environment. In other words, that only the fittest would survive. It must be remembered that this was before the publication of Darwin’s book.” LeConte said that the idea was wholly new to him and struck him very forcibly. To those who might wonder why Langdon Cheves did not publish this idea. Professor LeConte offered this explanation:

“No one well acquainted with the Southern people, and especially with the Southern planters, would ask such a question. Nothing could be more remarkable than the wide reading, the deep reflection, the refined culture and the originality of thought and observation, which were characteristic of them. And yet the idea of publication never even entered their minds.”

Like her father, Louisa McCord probably had some conversations with Professor LeConte, who had been a student of Louis Agassiz at Harvard. While holding Christianity and the Bible sacred and true, Mrs. McCord rejected literalism and agreed with Agassiz that mankind had a plurality of origins in the distant past. In espousing such views, however, she differed with two learned men of Charleston, both clergymen, who maintained the more orthodox view that humankind had a single origin. These were Dr. John Bachman, a Lutheran minister and a naturalist who collaborated with John James Audubon, and Dr. Thomas Smyth, an Irish-born Presbyterian minister and author.[6] Both men published books in 1850 upholding the unity of the races.[7]

Louisa McCord’s review of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that appeared in The Southern Quarterly Review in 1853 was a lengthy, scathing critique of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel. She went into many particulars of the book to refute Mrs. Stowe’s depiction of Southern slavery, but I think her views can best be summed up, at least informally, by this extract from a letter Mrs. McCord wrote to a female cousin in Philadelphia in 1852:

“Oh, Mrs. Stowe, one word of that abominable woman’s abominable book! I have read it lately, and I’m quite shocked at you, my dear cousin, Miss Mary C. Dulles, for thinking it a strong exposition against slavery. It is one mass of fanatical bitterness and foul misrepresentation wrapped in the garb of Christian charity. She quotes the Scriptures only to curse by them. Why, have you not been at the South long enough to know that our gentlemen don’t keep mulatto wives, nor whip Negroes to death, nor commit all the various other enormities that she describes? She does not know what a gentleman or a lady is, at least according to our Southern notions, any more than I do a Laplander. Just look at her real, benevolent gentleman as she means him to be, her Mr. St. Clare, or her sensible woman, Mrs. Shelby. Two more distressing fools and hypocrites I have never met with. Mrs. Stowe has certainly never been in any Southern State further than across the Kentucky line at most, and there in very doubtful society. All her Southern ladies and gentlemen talk coarse Yankee. But I must stop. Read the book over again, my dear child, and you will wonder that you ever took it for anything but what it is, i.e. as malicious and gross an abolitionist production, though I confess a cunning one, as ever disgraced the press.”

During the previous decade, in a speech given to the New England Anti-Slavery Convention in Boston in 1843, the prominent abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison had addressed these words to the slaves of the South:

“We know that you are driven to the fields like beasts, under the lash of cruel overseers or drivers, and there compelled to toil from the earliest dawn till late at night; that you do not have sufficient clothing or food; that you have no laws to protect you from the most terrible punishments your masters may choose to inflict on your persons; that many of your bodies are covered with scars, and branded with red hot irons; that you are constantly liable to receive wounds and bruises, stripes, mutilations, insults and outrages innumerable; that your groans are borne to us on every Southern breeze, your tears are falling thick and fast, your blood is flowing continually; that you are regarded as four-footed beasts and creeping things, and bought and sold with farming utensils and household furniture. We know all these things…”[8]

Mrs. McCord did not agree that Mr. Garrison knew much of anything, and like many other Southerners, she was not only outraged by his false depiction of American slavery, but also by his call that the slaves should resort to insurrection and violence. Unlike Mrs. Stowe or Mr. Garrison, Louisa McCord possessed an intimate knowledge of Southern slavery, and she knew the laws of South Carolina that dealt with it and wrote about them in her essay “British Philanthropy and American Slavery,” which was published in DeBow’s Review in 1853. It was a response to some anti-slavery articles that had appeared in British publications. One of these, a favourable review of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, claimed that slave owners had uncontrolled power over their slaves, who were no more than property. Mrs. McCord responded by writing: “The sweeping assertions so constantly made that our laws are in their general bearing cruel or neglectful of the slave is entirely unfounded. The truth is that our laws are most carefully protective of the slaves.” She drew from an 1848 pamphlet published by John Belton O’Neall, The Negro Law of South Carolina, presenting some of the passages that refuted such claims by abolitionists. Among these were the following (quoting O’Neall):

“Also, slaves by the Act of 1740 are declared to be chattels personal. Yet they are also in our law considered as persons with many rights and liabilities, civil and criminal…By the Act of 1821, the murder of a slave is declared to be a felony without the benefit of clergy…The act of 1740 requires the owners of slaves to provide them with sufficient clothing, covering and food…By the Act of 1740, slaves are protected from labour on the Sabbath day…”

I think it’s worth noting that only a year after this article was published, two white men, one of them from a wealthy Charleston family, were executed in Walterboro for the murder of a slave.

On the subject of women, Louisa McCord was perhaps at her most conservative and traditional. She opposed suffrage for women and argued that women were best fulfilled in the domestic sphere. Her 1852 essay “Enfranchisement of Woman” was written in response to a number of articles calling for what came to be known in the 20th century as women’s liberation. In it Mrs. McCord wrote very sardonically of women who demanded equality with men:

“A true woman, fulfilling a woman’s duties…a high-minded intellectual woman, disdaining not her position…an earnest woman striving as all earnest minds can strive, to do and to work as the Almighty laws of Nature teach her that God would have her to do and to work, is, perhaps, the highest personification of Christian self-denial, love and charity which the world can see. God, who has made every creature to its place, has, perhaps, not given to woman the most enviable position in creation, but a most clearly defined position he has given her…Out of it, there is only failure and degradation.”

Women who demanded equality with men, she thought, had abandoned good sense and decency. Later in the same essay, Mrs. McCord wrote:

“Woman will reach the greatest height of which she is capable – the greatest, perhaps, of which humanity is capable – not by becoming man, but by becoming, more than ever, woman…The woman must raise the man by helping, not by rivalling him. Without woman, this world of mankind were a wrangling dog-kennel. Could woman be transformed into man, that same result would follow. She it is who softens; she it is who civilizes; and, although history acknowledges her not, she it is who, not in the meteoric brilliancy of warrior or monarch, but in the quiet, unwearied and unvarying path of duty…Woman is neither man’s equal or inferior, but only his different.”

The third subject that interested Mrs. McCord was political economy and, in this area, she was a proponent of principles known as laissez-faire. I’ve mentioned her translation of Frédéric Bastiat’s book and his influence on her thinking. Why was Bastiat important? A modern libertarian economist, Murray N. Rothbard, wrote that Bastiat was: “A lucid and superb writer, whose brilliant and witty essays and fables to this day are remarkable and devastating demolitions of protectionism and all forms of government subsidy and control. He was a truly scintillating advocate of an untrammeled free market.” Bastiat also emphasized the importance of private property and argued that the rights of all in society are best served when property rights are respected. The foreword to Mrs. McCord’s book, written by her husband, explained the importance of its subject matter, contending that it is needful for every citizen to understand:

“…that it is not nature, but ignorance and bad government which limit the productive powers of industry, and that in fulfilling the duty of a legislator, public and not private interests, should form the exclusive object of his legislation; that ‘he is not to frame systems and devise schemes for increasing the wealth and enjoyments of particular classes, but to apply himself to discover the sources of national wealth and universal prosperity…”[9]

I think what’s referred to here is what has been called crony capitalism. The economist and author Thomas DiLorenzo has written that such government favours and subsidies were the cornerstone of the Whig Party in America, and later the Republican Party, along with a nationalized banking system and high protectionist tariffs. “Protectionists,” wrote DiLorenzo, “have always made the case for their special-interest policies by producing a blizzard of plausible-sounding but incorrect theories designed to blur the public’s knowledge about their true intentions.” It was the object of Bastiat’s book, Sophisms of the Protective Policy, to refute these plausible-sounding but incorrect theories, these sophisms advanced against free trade. Bastiat not only criticized protectionists, but also socialism and the socialistic tendencies of his own government in France. In his essay called “Government,” he asked the question: “What is government?” Bastiat answered: “I have not the pleasure of knowing my reader, but I would stake ten-to-one that for six months he has been making Utopias, and if so, that he is looking to Government for the realization of them.” Mrs. McCord’s article, “Justice and Fraternity,” published in The Southern Quarterly Review in 1849, was a critique of socialism and utopias enforced by law, and it drew heavily on an article of the same name by Bastiat. She quoted him as saying:

“…while political economy asks from the law universal justice and nothing more, socialism, in its diverse forms, requires, over and above this, that the law should guaranty the realization of its favorite dogma of fraternity [or brotherly love]…We are not convinced of the possibility of enforcing brotherly love upon the world…To decree it is to annihilate it. The law may force a man to be just, but vainly would force him to be generous…But when, in the heart of society, the principle is established that fraternity shall be imposed by law; – that is to say, in plain English, that the produce of our labor shall be divided by law, without any reference of regard to the rights of labor itself, – who can say where this fantastic principle will stop, in what for the caprice of a legislator may invest it, or what institutions may be established by its whimsical decrees? On such conditions can society exist?”[10]

Frederic Bastiat’s defense of free trade resonated with Mrs. McCord as a Southerner because American protectionism in the form of the tariff had been one of the principal sources of conflict between the South and the North for many decades. It came to a head in the Tariff of Abominations and the nullification crisis in the early 1830’s and never really went away. In 1860, when South Carolina seceded, the Secession Convention published a document entitled The Address of the People of South Carolina. One of its chief complaints against the government of the United States was the tariff. After comparing the position of the South to that of the American colonists in 1776, the Address stated:

“The Southern States are a minority in Congress. Their representation in Congress is useless to protect them against unjust taxation…For the last forty years, the taxes laid by the Congress of the United States have been laid out with a view of subserving the interests of the North. The people of the South have been taxed by duties on imports, not for revenue, but for an object inconsistent with revenue — to promote, by prohibitions, Northern interests in the productions of their mines and manufactures…The people of the Southern States are not only taxed for the benefit of the Northern States, but after the taxes are collected, three-fourths of them are expended at the North.”[11]

The Morrill Tariff bill was working its way through the U.S. Congress in 1860. It passed the House of Representatives in May of that year and passed in the Senate early the following year. It was signed into law by President James Buchanan on March 2nd, 1861, two days before the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln, and it raised the average tariff rate from about 15% to over 37%, with a greatly expanded list of items covered. The Confederate Constitution of 1861 outlawed such protectionist tariffs, and the economist Charles Adams argued in his book, When in the Course of Human Events, that the Confederacy’s transformation of the South into a free trade zone was the principal catalyst for Northern aggression.[12]

The War that began in 1861 ended most of Mrs. McCord’s literary efforts. She turned all her energies instead to the support of the Confederate Army and became well known and highly revered in South Carolina for her tireless work for the soldiers. Though devastated by the death of her adored son, who died in 1863 as a result of wounds from the Battle of Second Manassas, she continued to devote herself to feeding and clothing soldiers and nursing the wounded in the military hospital in Columbia. She was the president of the Soldiers Relief Association and the Ladies Clothing Association of that city. Mrs. McCord owned a house in Columbia, which General Oliver Otis Howard, Sherman’s second in command, used as his headquarters when the city was occupied by U.S. forces in February, 1865. Just before Howard arrived, a crowd of Federal soldiers began ransacking and pillaging the house. One of them seized Mrs. McCord by the throat, throttled her, and tore a watch from her dress. When General Howard arrived, the soldiers were still at work and Mrs. McCord wrote that the General saw these men in the very act of looting. A little while later, Howard caught some of his own men attempting to set fire to the McCord residence. He ordered them to stop, but when he saw that Mrs. McCord was nearby and had overheard him, he approached her and laid the blame on the burning cotton flying about.

On one occasion, when a ball of burning cotton was found inside a back entryway of the house, General Howard commented again that it was very remarkable how the cotton kept blowing about. Mrs. McCord answered him: “Yes, General, very remarkable through closed doors.” Earlier that same day, Mrs. McCord had received an ominous note urging her and her family to leave Columbia. She wrote of it:

“One of my maids brought me a paper left, she told me, by a Yankee soldier. It was an ill-spelled but kindly warning of the horrors to come, written upon a torn sheet of my dead son’s notebook, which, with private papers of every kind, now strewed my yard. The writer, a lieutenant of the army of invasion, said that he had relatives and friends at the South, and that he felt for us, that his heart bled to think of what was threatened. ‘Ladies,’ he wrote, ‘I pity you. Leave this town. Go anywhere to be safer than here.’”

This was written in the morning. The fires were in the evening and night. In her recollections of the War, Mrs. McCord’s daughter Louisa, later Mrs. A.T. Smythe, described U.S. soldiers who invaded and pillaged their yard and outbuildings and then their house:

“Without any warning our back gate was burst violently open, and in rushed pell-mell, crowding, pushing, almost falling over each other, such a crowd of men as I never saw before or since. They seemed scarcely human in their fierce excitement, the excitement of greed and rapine. Before we could look, every door was burst open and every room gutted of its contents. They robbed even the negroes. What they couldn’t take, they spoiled. We stood petrified and fascinated at the window, watching. There was a terrible system and skill about it all. The only confusion was caused by their anxiety to get ahead of each other, and the speed with which they dashed from side to side was wonderful. They smashed, tore, and pocketed everything they could get at.”

In her memoir, Louisa Smythe also described another conversation between her mother, Louisa McCord, and General Howard:

“[Howard] tried to excuse the shelling, when my mother asked him how they as soldiers brought themselves to shell defenseless women and children in their beds, by some platitudes about the sad necessities of war, and how he thought of his own children in their little beds, etc., etc., but how this had to be in retaliation for the other methods of warfare pursued by us, and then told how some promising young man had been blown up and terribly injured by a submarine torpedo near Savannah. Mamma listened very quietly and expressed her sorrow at anyone suffering, but said…that it was a new idea to make women and children atone for the wounds and deaths of soldiers. For this, the general had no answer.”

Because of General Howard’s presence in it, the McCord home was not burned, and it still exists today as a historic property in Columbia. After the war a committee of citizens was appointed to collect testimony concerning the burning of Columbia by Federal troops. Over sixty affidavits from eyewitnesses, including Mrs. McCord, were assembled. They were presented along with the committee’s report to the Mayor of Columbia in November 1868, but these records inexplicably disappeared from the municipal archives during the carpetbagger administration of the city. When a search was made for the original report and affidavits in 1878, they were nowhere to be found. Like other South Carolinians, Mrs. McCord was deeply affected by the outcome of the war, which resulted in the destruction of a civilization she had tried to defend. The heart that had already been broken by the death of a son and her country was broken again when she was finally persuaded to take the hated oath to the United States in order to sell her house in Columbia. In March 1870, during South Carolina’s so-called reconstruction, she penned a poignant letter to the sculptor Hiram Powers inquiring about a portrait bust of her father which had been commissioned before the war. In it, she wrote:

“We are destroyed, and I fear as a people passed from life forever. The true-hearted among our survivors have to look with pride only upon our sufferings and upon the graves of our dead. We fought for our rights and our liberties. Our very boys were heroes in endurance and in death, but now ground down and writhing beneath the heel of a brutal conqueror, none can even live without giving up something of the purity of his feelings by submission to the unblushing, utterly lawless tyranny of a brutal rule. And the wreck of as noble a people as ever trod God’s Earth must, I fear, inevitably fall away from its higher characteristics.”

For several years after the War, Louisa McCord lived with various relations, and in 1871 she left South Carolina and resided for a while in Canada. Around 1877 she returned to Charleston to live with her daughter, Louisa, and her son in law, Augustine T. Smythe. She died in 1879 and is buried in Magnolia Cemetery. I will close with a brief excerpt from a tribute to Louisa McCord written by her friend Miss I.D. Martin:

“Her eloquent pen was devoted to her country’s service, as was every fiber of her being. Perhaps her last public writing was an appeal to the women of the state to join the effort to raise a monument to South Carolina’s dead of the Confederate Army. When some of the women of Columbia inaugurated this movement, they naturally turned to her as their leader. The silent sentinel on that monument, keeping guard over the deathless memories of the past, does not attest more fully to the valor and patriotism of the men in the field than it does to the heroism and fidelity of the women at home, foremost among whom was Louisa S. McCord of South Carolina.”

****************

[1]A brilliant economist, Bastiat is probably best remembered today for his excellent 1850 essay, The Law: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Essays_on_Political_Economy/The_Law

[2]Unfortunately, only the first volume is presently available on archive.org.

[3]In 1997, Lounsbury published a one-volume collection entitled Louisa S. McCord: Selected Writings: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/louisa-s-mccord-richard-c-lounsbury/1101800208?ean=9780813917603

[4]For a more recent biography of George Mason, see: https://archive.org/details/georgemasonforgo00broa/page/n5/mode/2up

[5]See, for example, Lincoln’s statements in his debates with Stephen Douglas at Ottawa (1st debate, 21 August 1858): https://digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-lincoln%3A36541 At Charleston (4th debate, 18 September 1858): https://digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-lincoln%3A35378 As quoted by Douglas at Galesburg (5th debate, 7 October 1858): https://digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-lincoln%3A35378 At Quincy (6th debate, 13 October 1858): https://digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-lincoln%3A36741 And at Alton (7th debate, 15 October 1858): https://digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-lincoln%3A34692

[6]To say nothing of differing with one of the South’s most influential theologians, her fellow South Carolinian James Henley Thornwell. For Thornwell’s rejection of polygenesis, see The Rights and Duties of Masters (1850), 10-11: https://archive.org/details/rightsdutiesofma00thor/page/10/mode/2up

[7]For Bachman’s work, The Doctrine of the Unity of the Human Race Examined on the Principles of Science, see: https://archive.org/details/doctrineunityhu01bachgoog/page/n6/mode/2up For the 1851 edition of Smyth’s book, The Unity of the Human Races Proved to be the Doctrine of Scripture, Reason, and Science: With a Review of the Present Position and Theory of Professor Agassiz, see: https://archive.org/details/unityofhumanrace00smyt/page/n33/mode/2up

[8]Garrison printed this in The Liberator, 2 June 1843, a scan of which can be found here: https://fair-use.org/the-liberator/1843/06/02/the-liberator-13-22.pdf

[9]L.S.M., Sophisms of the Protective Policy, 3-4. The italics are original.

[10]L.S.M., “Justice and Fraternity,” 358-361. Italics original.

[11]See pages 6-7.

[12]See Article I, Section 8, Clause 1.

Thank you for the introduction to this great woman!

I would argue MS. Louisa S. McCord was the first Libertarian economic thinker in the United States. She was an incredibly gifted woman.