This article was originally published in Southern Partisan Magazine in 1997.

“Being a Southerner is a spiritual condition, like being a Catholic or Jew.” So wrote Richard Weaver in his essay “The South and the American Union” in The Lasting South (1957). The South’s experience during the war for its independence, he added, only confirmed this separateness of spirit and a need to be a separate nation.

The South might be viewed as an American Ireland, Poland or Armenia, not indeed unified by a different religious allegiance from its invader, but different in its way of life, different in the values it ascribed to things by reason of its world outlook, and made more different after the war by its necessary confrontation of the tragic view . . . .”

With the United States seeking independence for countries around the world, Weaver wrote, “it has certainly been handsome of the South not to raise the question of its own independence again.”

Why that question has not been raised in the political arena by Southerners of late is one of the puzzling and intriguing questions of late 20th century America. With the re-emergence of independent nation-states rising from the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union and the stirrings of nationalism among other culturally and politically suppressed peoples around the world, American Southerners may well constitute the major nationality in the free world without a politically active separatist movement.

The possibility of a politically independent Southern nation is not as far-fetched as many might think. Increasing numbers of scholars are writing about the probable dismantling of large nations. Robert Kaplan, in Atlantic Monthly of February 1994, predicted substantial changes in national boundaries in the next century, possibly including the United States. These changes will be fueled, Kaplan believes, by environmental, demographic, cultural, ethnic and religious stresses.

There are substantial arguments in favor of these national divisions, articulating the virtue of small nations. The English Canadian Jane Jacobs, in her Cities and the Wealth of Nations (1984), argues for the theoretical division of large nations into smaller sovereignties in order to promote economic prosperity. One of her principal defenses is that a uniform currency for a large nation triggers the wrong economic responses in many of its cities because of differing circumstances and needs. In her earlier work, The Question of Separatism: Quebec and the Struggle over Sovereignty (1980), she viewed small nations as offering “the only promising arrangement” for the type of active government prevalent today, beset by bewildering bureaucracy and inefficiencies which large nations land centralization of power greatly compound. She was sympathetic to Quebec secession also because it would promote the flourishing of the culture of French Quebec on its own terms, the only way, she rightly notes, any culture can flourish.

Harry Schultz, a well known inter-national investment consultant, in 1991 published On Re-Making the World: Cut Nations Down to Size. His major thesis was that large nations, including the United States, should break up into smaller nation-states reflecting their cultures, economies, religions, races and topography. He believes that this would reduce tensions and bloodshed and promote individual freedom, representative government and economic prosperity. James Ronald Kennedy and Walter Donald Kennedy, in The South Was Right (1994) advocated the resumption of sovereignty by the Southern states and establishment of a new Southern nation-state failing the reestablishment of a federal republic of limited powers for the entire United States. Thomas H. Naylor, professor emeritus of economics at Duke University, and Wlliam H. Wilimon have recently published Downsizing the U.S.A. (1997). Naylor believes that the United States should “begin planning the process to facilitate orderly secession of states that want to assume more responsibility for their own destiny.”

Long before the fall of Communism and the new possibilities for nationalism which that momentous development unleashed, Robert Whitaker and John Shelton Reed in the early 1980s raised the issue of Southern Nationalism in the pages of Southern Partisan. Whitaker, seeing the South as a nation, urged Southerners to pursue their interests as Southerners politically, and therefore save the South from the destructive forces of the “melting pot” policies of the modern U. S. government. The United States Constitution was designed to facilitate regional cultural identify, Whitaker argued, not destroy it. Failing a return to the original principles of the Constitution, Southerners have the option of political separation, Whitaker maintained.

Noting influential separatist movements in Scotland and Quebec and in other Western countries, John Shelton Reed asked why the United States has been immune. He gave some very cogent reasons, but also wrote in 1982 that he wouldn’t be surprised to see a Southern separatist movement emerge. “I for one would find an American politics where the proper balance between federal power and decentralization was subject to debate preferable to one where an arrogant central government recognizes no limits on its authority.”

An important Southern separatist movement has appeared, yet oddly there remains little debate in Southern State capitals or in Washington. The discussion focuses on the federal-state balance of power and not on the constitutionality of current federal power. A Southern nationalism movement headed by respected Southern intellectuals emerged in June 1994 with the formation of The League of the South, a fast growing organization with thousands of members, and chapters currently being formed in the South, and beyond. What feeble attempts have been made to return functions back to the states, as in last year’s welfare reform, are done solely for expediency, under federal control. All powerful Washington could take those functions back at any time.

The devolution of power being seriously discussed and even implemented in many Western countries has often been fostered by a separatist movement. Perhaps it will take serious discussion of Southern political independence to shake the Southern establishment loose from its infatuation with preserving cur-rent economic prosperity at all costs, including the loss of control over one’s political, cultural, and economic affairs. In point of fact it is hard to see how devolution of power to the states or to an independent Southern nation would weaken economic prosperity. Harry Schultz believes the process of nation-building itself would boost the economy, and many believe that smaller governmental units with closer to home concerns would prove a boon to local prosperity.

The South as a Nation

Contrary to what United States’ propaganda teaches, the South is a nation. The power, influence and ubiquitousness of the modern nation-state leads many to think of a nation solely in terms of a politically independent entity. However, the word “nation” also means a people with common attributes, even without the existence of a political state of their own. The American Heritage College Dictionary, 1997 edition, gives as a definition of nation: “A people who share common customs, origins, history and frequently a language, a nationality.” The root meaning of “nation” reveals why a nation is fundamentally a people, and why we speak of “nation-states” and not just “nations.” The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (1966) traces the origin of the word “nation” to the Latin natio(n-),meaning “breed, race, stock,” which is formed from nat-,the past participle stem of nasci, to be born. Thus blood, kin, family past, tradition, and the culture accompanying them are all bound up in what it means to be a nation. Once Southerners understand that they are a classic nation by the core meaning of the word, they would recreant not to seek the preservation of their own unique culture and society.

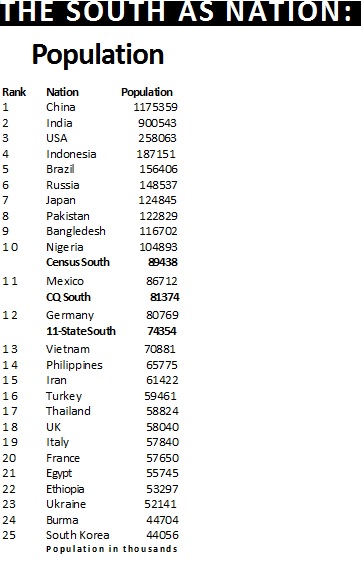

The South is not only a nation, it is one of the largest and most important nations on earth. It will likely surprise most Southerners, and Americans in general to learn that if the 11 states of the historic Confederate States of America were a politically independent nation, the new nation-state would have the fourth largest gross domestic product on earth, at over $1.5 trillion, close behind the united Germany, which in turn would follow Japan and the rest of the United States. In population, a Southern nation-state of the former Confederate States, with 76 million people (1994), would be the 13th most populous on earth, again close behind Germany (81 million), and with considerably more people than France (58 mil-lion) or the United Kingdom (also 58 million). The American South as a nation-state would take its place among world powers.

But much more important than sheer power are the policies which an independent Southern nation would pursue. Again, most people are unaware of how profoundly the South has been pulled leftward from its moorings by its association with the rest of the United States. The 1996 Presidential election provides a dramatic example of how much more conservative the South is than the rest of America. In fact, for the second Presidential election in a row, the modern political South of the 11 former Confederate States plus Kentucky and Oklahoma voted for the perceived more conservative candidate, the Republican nominee, against the winning Southern ticket of Clinton of Arkansas and Gore of Tennessee, candidates of the Democratic Party, perceived to be more liberal.

Other facts make the 1996 Republican victory in the South even more impressive. Dole, the non-Southern Republican nominee, was battling an incumbent President who represented the traditional party of the South, who talked like a Southerner and who displayed a folksy Southern manner. The media portrayal of Clinton and the Democrats as moderates was also a significant factor. They spoke moderate Democratic rhetoric and had a few good moves, such as welfare reform, to lend credence to the claim. The high black percentage of the Southern population which overwhelmingly supports Democratic candidates, makes Republican victories in Southern states all the more extraordinary.

Many Southerners, however, are coming to the conclusion that the national Republican Party, in spite of its rhetoric, is little better in a fundamental sense than the national Democratic Party. This is because the Republican Party will not, in Samuel Francis’s terms, defend the interests of the Middle American, and because it will not open an honest debate on federal-state power, much less strongly pursue increased local autonomy. This leaves Southerners at the mercy of a national will often fundamentally to the left of the Southern point of view.

North vs. South on the Issues

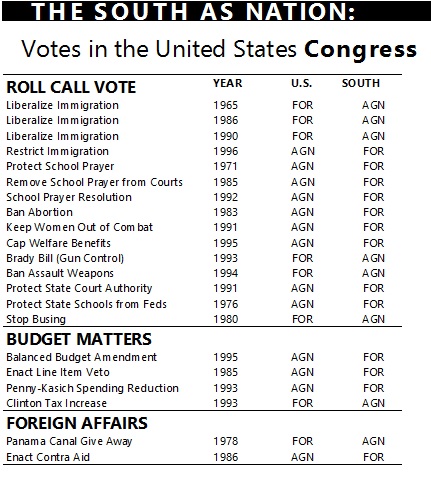

The truly telling divergence of Southern values from those of the conglomerate American nation-state, how-ever, can be found in votes in the U. S. Congress since 1965 concerning a number of the most important issues facing Americans today. These votes demonstrate how much more reflective of the South’s traditional conservative values a politically independent Southern nation would be. On a number of key policy issues, Southern U. S. Senators and Congressmen have voted differently from their non-Southern counterparts. This means that a politically independent nation composed of the South alone would have a different policy on these issues. These Southern votes are not the imaginative creation of a frustrated Southern conservative. They are the actual votes of the thirteen-state South as designated by the Congressional Quarterly (CQ), one of the most trusted sources of United States Congressional action. CQ defines the South as the 11 historic Confederate States plus Kentucky and Oklahoma. Politically, these 13 states best constitute the Southern States of the United States.

One issue, immigration, has the power to transform the South and the United States fundamentally and unalterably. Time magazine recognized this in a 1990 cover story article when it noted that the new immigration— which it called the “browning of America”—”will alter everything in society, from politics and education to industry, values and culture.” It was Lyndon Johnson’s Immigration Reform Act of 1965 which opened the flood gates to massive Third World immigration. The United States as a whole, including conservative Republicans outside the South, voted overwhelmingly for this watershed immigration reform. The vote in the U. S. Senate was 76-18 in favor, with House approval by a greater than 3-1 margin (318-95). The South was the only region to vote for stability and for a continuation of a Western oriented United States – though in fairness many at the time did not foresee the consequences of their vote. Southern House members voted more than 2-1 (75 to 34) against the ’65 Immigration Reform Act, while their counterparts in the Senate voted against the new order by the somewhat closer but still substantial margin 15-10. It may be noted here that outside the South the vote was 66-3 in favor of this major immigration reform in the Senate and 284-20 in the House. These votes, as do quite a number of others in this survey, demonstrate not only a difference, but an overwhelmingly substantial difference, in the policy outlook of Southerners from Americans living elsewhere.

The South continues to be the only major region of the United States to oppose liberal immigration policy. The Immigration Act of 1986 (amnesty to illegal aliens) passed the House 238¬173. Southern representatives voted strongly against, 70-49. The most sweeping revision of immigration law since the ’65 Act passed Congress by overwhelming margins in 1990, 89-8 in the Senate and 264-118 in the House. This law increased legal immigration by roughly 200,000 people annually, about a 40% increase, in spite of polls showing a majority of Americans opposed increased immigration. Southern House members voted against this immigration increase 60-54, going against the wishes of President Bush, who supported the measure on final passage. Last year, the South for the fourth time in modern history cast its vote in favor of a conservative immigration policy against the adopted measures of the United States. Representative Lamar Smith’s (R-Texas) immigration bill, which sought to reduce legal immigration, failed in March 1996 to win House approval by a 238-183 vote, while Southern House members voted in favor 79-54.

The Balanced Budget Amendment said to be the centerpiece of the Republican Contract with America in 1995 failed of passage once again— even in the first Republican-controlled Congress in forty years. The South has consistently voted for these amendments, which have been offered time and again, by the requisite two-thirds majority for constitutional amendments, and did so again in March 1995 by a Senate vote of 21-5.

The perennial issue of school prayer is one in which the South favors protective school prayer measures whereas the United States as a whole has repeatedly upheld the federal judiciary’s ban on school prayer. For example, a constitutional amendment in 1971 protecting school prayer won over-whelming approval by Southern representatives in the U. S. House by a vote of 84-23, but failed to garner the constitutionally required two-thirds majority among all House members. Taking the states’ rights stand, Southern senators in 1985 voted 18-7 in favor of a provision to bar federal courts from hearing school prayer cases, whereas the full Senate voted for continued federal scrutiny by a vote of 62-36, with non-Southern senators opting for continued federal court control of school prayer by the overwhelming vote of 55-18. And in 1 992 a resolution to express the sense of the Senate that the U. S. Supreme Court should reverse its earlier rulings prohibiting voluntary school prayer failed by a large majority in the full Senate but won the approval of 15 Southern senators, with only nine opposed.

Another highly emotional issue is abortion. A constitutional amendment in 1983 stating simply: “A right to an abortion is not secured by the Constitution,” and designed to overturn Roe v. Wade and return abortion decisions to the states, failed to garner even a majority in the Senate, though winning the approval of Southern senators by a vote of 18-7, more than enough to submit the amendment to the states for ratification.

Women in Combat. The South as a traditional society has always viewed itself as a protector of women. This chivalric policy was reaffirmed as late as 1991 in a vote to repeal the 1948 law prohibiting women from flying combat pilot missions. Senators overall voted over two to one to repeal the ban, but Southern senators voted 15-10 to retain the traditional view that women should not be exposed to military action.

Welfare reform is popular, but Southerners would enact tougher measures than the United States as a whole. In September 1995 the Senate rejected by a large 66-34 vote the House passed cap on welfare benefits to women who have additional children. Southern senators voted 16-10 for the cap.

Crime and gun control are hot button issues. Southern House members voted 79-57 against the Brady Bill in 1993, which established a five day waiting period for handgun purchases nationwide and provided for a national instant check of criminal records before a handgun may be sold. The full House passed the measure by a fairly substantial 238-189 vote. The following year, Congress approved an assault weapons ban, though Southern House members voted against the measure by a 2-1 margin. Southern representatives in the U. S. House also voted against the Omnibus Crime bill of 1994, 82-51. This law, among other provisions, incorporated the assault weapons ban, expanded the number of federal crimes, and overall, strongly increased the federal government’s role in fighting crime.

In 1991 the U. S. House of Representatives defeated an effort to prohibit federal habeas corpus appeals in cases that had a “full and fair hearing at the state level.” The South voted 77-47 in favor of this proposal, which was both a get-tough-on-criminals policy and a States’ Rights measure.

Though Southern representatives and senators now routinely give approval to civil rights legislation, they have consistently maintained a strong stand against busing, and had their voices prevailed, strong anti-busing measures long ago would have triumphed. The U. S. Congress has never seen fit to clamp down on court ordered busing. A strong States’ Rights proposal to bar federal courts from jurisdiction to hear cases involving public schools failed miserably in 1976 in the Senate by a 62-29 vote, but received an overwhelming 19-6 approval by Southern senators. (The vote against this measure outside the South was 56-10). A 1980 attempt to bar the justice Department from spending funds to require busing actually passed the full Senate 49-42, but no attempt was made to override President Carter’s veto. Southern senators gave this measure a whopping 5-1 margin of approval (20-4), many more votes than the two-thirds necessary to override a presidential veto.

In economic and fiscal policy the failure of even the new Republican controlled-Congress to pass a balanced budget constitutional amendment has already been mentioned. An attempt to end debate on the line item veto proposal failed 58-40 in 1985 (a three-fifths vote is required for cloture). Southern Senators mustered the cloture threshold by a 16-9 vote. The Penny-Kasich spending reduction package failed to pass the House in 1993, though Southern representatives gave it their approval. The Clinton deficit reduction package of 1993, which included a tax increase and spending cuts, passed muster in the full House but failed to win the Southern vote.

Due to the enormous power the U.S. Supreme Court has gathered unto itself, perhaps no single Senate vote has more potential importance than the confirmation of Supreme Court justices. Two Southern conservative judges, Haynsworth and Carswell, failed to win U. S. Senate confirmation to the Supreme Court in 1969 and 1970 respectively, largely because they were Southern conservatives, even though the usual obfuscating reasons were cited. Southern senators voted for each by overwhelming margin 22-4 in the case of Haynsworth and 20-6 for Carswell.

Liberals, disgusted with the power the two-thirds cloture rule gave conservatives, and in particular, Southern conservatives, pushed through the 1975 Senate rule change in the cloture requirement from two-thirds to three-fifths, making it easier to pass legislation over minority opposition. This rules change passed the Senate by an exceedingly ample 73-21. Southern senators cast 15 of the votes recorded against this measure, with nine in favor. Thus once again, contrary to popular belief and Northern propaganda, the South stood firm in its traditional role of protector of minority rights, against the national stampede for smoothing the route of bills through Congress. With the Republican Congressional victories of 1994 and 1996, Democratic liberals might well question the wisdom the change.

In the area of foreign policy and defense matters, some votes stand out. Even though Southern senators voted by a narrow margin in favor of the Panama Canal Treaty (14-12), this vote fell far short of the two-thirds necessary to ratify a treaty, which passed the Senate narrowly by a 68-32 vote. And if the South had been in charge, the Nicaraguan Contras would have had a much easier time fighting the Communists, as Southern House members voted 86-44 in favor of Contra Aid. (Non-Southerners voted to cut off aid.).

These 26 Congressional votes involving 16 social, economic, governmental, and foreign affairs policies make it abundantly clear what a major difference an independent Southern policy would make in our lives. The policy changes ushered in by the above Southern votes would produce a significantly different country more in keeping with the desires and lifestyles of a majority of Southerners. If the South had been an independent nation for the past 30 years it would have had budgets more closely in balance, less governmental taxation, a tougher policy on crime and welfare, greater local control over schools, protected prayer in the schools, a more conservative Supreme Court, and an immigration policy that would not flood the country with Third World immigrants.

The selective account of Congressional votes only serves as an indicator of the policy differences that exist between current Southern and national majorities. Other votes could have been included. The greater part of the legislative process is conducted before a bill ever reaches a vote by the full House or Senate. Bills are written, rewritten, and adjustments and compromises made long before they reach a final vote. In all of these stages the Southern conservative voice would be dominant if the South were in charge of its own destiny. Some of the Congressional votes cited would produce manifold consequences, as can perhaps most easily be seen in the approval of Supreme Court justices.

Furthermore, an independent Southern nation, freed of the need to compromise with more liberal policies emanating elsewhere in the United States, freed of the overbearing dominance of the federal government and loosened from the influence of liberal and leftist thinkers in other regions, in particular the Northeast, would be considerably bolder and more genuine in its conservative proclivities. To most Southerners, an independent Southern nation would be bliss compared to the liberal, leftist policies and schemes for societal reconstruction—almost all alien to the Southern world view—which flow out of Washington and Northern think tanks and universities in a never-ending stream of radical, reconstructionist agendas. These agendas authored by outsiders are designed to turn the South into the Utopian world bureaucrats and intellectuals desire without basis in the social reality of the South, and without concern for the views of the South, its culture, history, and traditions.

Conclusion

The question we face is simply this. Shall Southerners have charge of their own destiny, preserving for the future their culture and their values, or shall we continue to be molded to alien ideas, until at last the South has ceased to be a recognizable entity? Though many refuse to admit it, the United States has become a vast centralized power, overwhelmingly dominated and controlled by a liberal-leftist intelligentsia who continually pull this country to the left, against the wishes of the Southern people. The best hope, perhaps the only hope, for the South lies in an independent Southern nation, where we can at last be free to pursue the life we desire. If we were an independent nation again, we would be making our own unique contribution to civilization, benefiting mankind at large and preserving our own unique culture. If the South only believed in itself again, it could rise to true greatness not measured by material wealth alone, but more importantly, by the things of the spirit. Let it not be said of us that we allowed the South we love to perish.