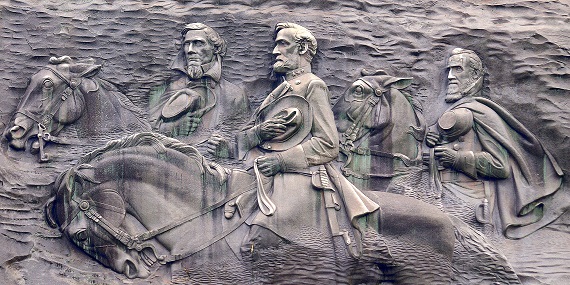

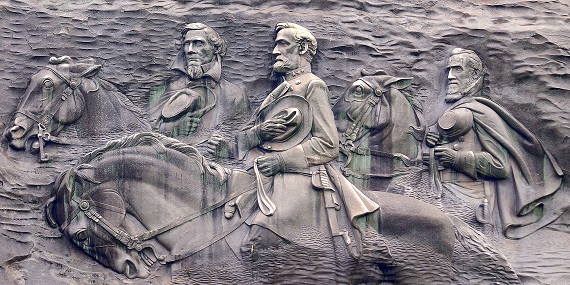

There are really only two basic opinions when it comes to the world’s largest carving on the face of the fifteen million year old granite monolith just outside Atlanta, Georgia . . . revere it as an important chapter in American history or destroy it as a shameful altar to the Ku Klux Klan. While there are many Americans with their own personal or political agendas concerning the mammoth monument at Stone Mountain, such as the former minority leader of the Georgia House of Representatives and the unsuccessful candidate for that State’s governor in 2018, Stacy Abrams, who demands that the famed Confederate memorial be sandblasted from the face of the mountain, many others, even foreign visitors, take a far different view of the famed carvings. In March of last year, a lady from Japan named Yumiko Yamamoto, the president of a group called Japanese Women for Peace and Justice, made her first visit to Atlanta and on her tour of Stone Mountain she was greatly impressed by not only the massive equestrian figures of President Jefferson Davis and Generals Robert E. Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson, but also the inscription on the monument’s plaque by Beverly M. DuBose, which reads; “The vast majority of those who fought and died for the Southern Confederacy had little in worldly goods or comforts. Neither victory nor defeat would have greatly altered their lot. Yet, for four long years they waged one of the bloodiest wars in history. They fought for a principle: The right to live life in a chosen manner. This dedication to a cause drove them to achieve: A monument of greatness which endures to this day.” Ms. Yamamoto gave a talk about her experience after she returned to Tokyo the following month and an account of her visit appeared later in the “Shukan N. Y. Seikatsu,” a Japanese newspaper in New York City, in which she was reported as saying; “Although the Confederates lost the Civil War, they praise the courage and honor of those who fought and died for the Confederacy. I thought Japanese should pass down our story just like their words to the next generation. Japan (also) lost the war, but we should honor those who fought and died for our country with the words just like I found at Stone Mountain Park.”

Sadly, however, the mental malady that author Paul Graham aptly termed “Confederaphobia” has not only become endemic throughout America, but the virus has spread to places as far away as Japan. In Japan, Ms. Yamamoto’s Stone Mountain comments were attacked by the far-Left group FeND, the “Japan – U. S. Feminist Network for Decolonization, a virulent activist organization that opposes not only the Japanese Self Defense Force, but the presence of all American troops throughout the Pacific area, even those stationed on U. S. soil in Guam and Hawaii. FeND called the Georgia monument “infamous” and linked it not to the heritage and history of those who fought and died for what they believed, but only to the 1915 reincarnation of the once defunct Ku Klux Klan. What the Japanese group, like so many others in the United States, either chose to ignore or failed to understand is that the vast majority of the up to six million latter-day Klan members who grew from the mere handful that resurrected the Klan atop Stone Mountain resided in the North. The Klan that rose to power above the Mason-Dixon Line soon became a potent political and social force during the 1920s, a force that elected a large number of United States senators and congressmen in several Northern States, as well as many Northern governors and hundreds of local officials.

The fact that some extremists may choose to use Stone Mountain as a rallying point from time to time, just as such groups misuse the Confederate Battle Flag, is actually irrelevant, and does not detract from the true purpose of the memorial. Some wiser voices have called for compromises that would keep the Confederate memorial intact but add other monuments that the opposition could support, such as reviving the 2015 proposal by the Stone Mountain Memorial Association that a mountaintop bell tower be erected in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King’s 1963 “Dream” speech in which he said; “Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.” One of the leading advocates of such moves is the chief operating officer of DeKalb County in which Stone Mountain is located, Michael Thurmond, who is also the only black member of the Memorial Association. These attempts at a return to sanity, however, continue to be drowned out by the constant drumbeat of anti-Confederate and anti-Southern hatred and propaganda, such as last year’s “Graven Image” documentary from PBS which dwelled mainly on the connection between Stone Mountain and the Klan, as well as attempting to promote the false theory that the monument was created merely as a racist symbol to support so-called “white supremacy.” Those like Stacy Abrams and the NAACP who seek to use this hatred for political gain also continue to cry that the carving is a blight on the State of Georgia and should be removed. With such people, there is no compromise nor any hope of reconciliation when it come to anything connected to the Confederacy, including Stone Mountain.

The true story of the monument’s origin, however, began on June 14, 1914, with an editorial by the editor of the “Atlanta Georgian,” John Temple Graves, which read in part; “Just now, while the loyal devotion of this great people of the South is considering a general and enduring monument to the great cause fought without shame and lost without dishonor, it seems to me that nature and Providence have set the immortal shrine right at our doors.” Without any thought of racism or white supremacy, Graves was merely calling for a monument to those who rose up to defend their families and their homes, as well as the South . . . and he felt that the face of Stone Mountain was the slate upon which it should be etched. Eighty-five year old Helen Plane of the Atlanta United Daughters of the Confederacy agreed and started a movement to fund the project. Several people were considered to create the memorial, including the renowned French sculptor Auguste Rodin, but it was finally decided that an American, Gutzon Borglum, should do the work. The initial thought was to create only a likeness of General Lee, but Borglum envisioned something far more massive. His idea was a frieze of up to a thousand figures that would include hundreds of soldiers being led by President Davis and Generals Lee and Jackson. It was estimated that the project would take eight years to complete at a cost of at least two million dollars. The First World War delayed work on the carving and by 1924 only the head of General Lee had been completed. The following year Borglum left Stone Mountain and a few years later started the presidential project on Mount Rushmore in South Dakota. Work on Stone Mountain was again started in 1925 under the direction of Virginian sculptor Augustus Lukeman. That same year the United States Congress and President Coolidge, without any protest demonstrations or anti-Confedrate outcry, authorized the United States Mint to issue a half dollar commemorative coin for Stone Mountain to help raise funds for the project and employed Borglum for its design. The face of the coin depicted Generals Lee and Jackson conferring, with the reverse side bearing the inscription “MEMORIAL TO THE VALOR OF THE SOLDIERS OF THE SOUTH.” The Stone Mountain half dollar quickly became the most popular of the twenty-three commemorative coins which had been minted by the United States since the initial one in 1892 for the Columbian Exposition. Three years later, the new funding began to run out and work was again halted in 1929 . . . and remained so when the Great Depression swept across the nation the following year. In 1941, Governor Eugene Talmadge formed the Stone Mountain Memorial Association in an effort to restart the carving, but the exigencies of another world war again intervened and the project lay dormant until 1958 when the State of Georgia under Governor Marvin Griffin purchased the property for one and a quarter million dollars and hired Missouri sculptor Walter Hancock, who had just created a World War Two memorial in Philadelphia, to finish the work. The carving on Stone Mountain was finally started again in 1964 and completed in 1972 . . . the eight-year period that was originally estimated for the entire project back in 1915.

Since its dedication in 1972, the Confederate memorial and its surrounding park have had over four million visitors a year, and it has become one of Georgia’s most popular tourist attractions. Stone Mountain, however, has now become something a bit different from what John Temple Graves had originally envisioned in 1914. Rather than standing alone as a grand and solemn monument to honor those who fought and died for the Confederacy, the area has today become little more than a theme park with the monument as its dramatic backdrop, a park replete with a train ride, a recreated antebellum village, a giant 3-D theater, a miniature golf course and a large playground filled with dinosaur replicas, as well as serving as the venue for many various demonstrations, including those that urge the removal of the park’s only true identity and purpose. One can now but hope that sometime in the not too distant future some measure of sanity will finally prevail, with politics and prejudice being laid aside and the monument at Stone Mountain regaining its intended place as an important part of American history and heritage. It might be further hoped that the monument would not only continue to serve as a memorial to those who fought and died for their country, but also become one that would fulfill Dr. King’s dream of a mighty symbol for unity and racial reconciliation . . . a monument as enduring as the Stone Mountain granite that architect Frank Lloyd Wright used in 1919 to construct the earthquake-proof foundation of his iconic Imperial Hotel in Tokyo.