Editor’s note: The author of this piece won the Bennett History Medal in 1908 for this essay, and was published in the June 1909 volume of the John P. Branch Historical Papers. The Bennett prize is still awarded annually by Randolph Macon College to the best undergraduate history paper. This particular essay displays a depth of understanding even contemporary graduate students lack in their general scholarship and is devoid of the deconstructionist political activism of modern “histories.” The historian should seek to understand his subject, not pass presentist moral judgements on people of a different time.

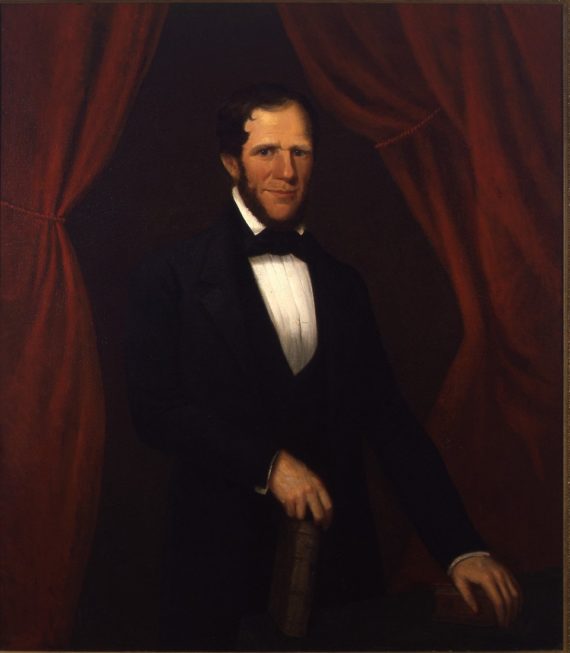

Thomas Roderick Dew, teacher, political economist, and man of letters, was born the fifth day of December, 1802, in King and Queen county, Virginia. His father was of good Scotch stock, and like most other Virginia gentlemen of his time, was the owner of a large plantation. The son, Thomas, seems to have been of a more sober temperament than the average boy of his day and circumstances and preferred to remain at home reading and studying than to be abroad in the fields riding and hunting. He had a great passion for history and early became conversant with the principal facts of ancient and modern history.

Quiet and retiring in manner, and old for his years, he developed a decided literary taste, and the desires of an eager intellect were encouraged by his parents. When but fifteen years of age he entered William and Mary College at Williamsburg, Virginia, which was at that time the leading educational institution in the South. He was a close and indefatigable student while at college and graduated in 1820, being then only eighteen years of age. This sedentary life, however much it had conduced to his intellectual growth and improvement, had not had a salutary effect upon his body, so that after he had finished his schooling at William and Mary College he spent two years traveling abroad for his health. He availed himself of this opportunity to further pursue his studies in history and politics, so that when in 1827 he was assigned to the chair of “History, Metaphysics, Natural, and National Law, Government, and Political Economy,” it would have been difficult to find in the United States his equal in scholarship, especially in the subjects which he taught.

When we consider the idea of a man holding a collegiate chair with such a list of departments, to each of which he was required to devote at least three lectures a week, we stand amazed. Add to this the fact that he was engaged in writing voluminous essays and treatises which required and have shown great care and research in their preparation, besides a large number of newspaper and magazine articles, and the necessarily large correspondence encumbent upon a “savant,” we must admit that “verily there were giants in those days.”

As noted above, William and Mary, prior to the opening of the nineteenth century, had been the foremost college in America, south of Boston, but the attendance had been greatly reduced previous to its being taken in charge by Professor Dew. For this there were several reasons. Already the North and the South had become divided upon political questions, and were distinct political divisions, and the attendance at schools followed the line thus drawn, so that William and Mary now got its students entirely from the South and not many Southern students went North. Moreover the climate at Williamsburg was not very healthy. The location had become out of the way and undesirable. Repeated attempts had been made to have the college moved to Richmond, and finally, as the natural offspring of William and Mary there came the establishment of the University of Virginia in 1819.

In 1836, when Dew succeeded Dr. Empie as president of the college, a new era was inaugurated, and a golden period it was for the college. In the first three years of his presidency the roll was almost doubled. To quote a literary contemporary of Dew’s,” “his amiable disposition, fine talents, tact at management, great zeal and unwearied assiduity were the means of raising the college to as great prosperity as had ever been its lot, notwithstanding many opposing difficulties.”

The Law Course was improved and enlarged, and now numbered thirty students. From 1779 to 1826 it had been presided over by George Wythe and St. George Tucker, both eminent statesmen and scholars. But probably no course was more exhaustive, or its teacher more thoroughly grounded in his subject than that of History and Political Economy, taught by Dew from 1827 until his death in 1846. His course in History was the most thorough and comprehensive of any in America at that time.

It has been said that in the North men gave the care of the State to professional politicians, while in the South, the ordinary work being done by slaves, the white people had time for study and make practical use of their studies in politics, preferring themselves to become the statesmen of their day. This is undoubtedly true, and probably no one in the entire South did more to stimulate the growth of this interest and personal activity than did Dew. He was among the first teachers of Political Economy in the South. Familiar with the best results of French, German, and English scholarship in the field of classical history, he taught his students to see analogous parallels between ancient history and politics, and that of our own State and nation. In the study of such subjects the South was far ahead of the North, where they were not taken up until after the Civil War, and this accounted in large measure for the conspicuous merit and superiority of Southern leaders in political life.

In Dew’s class in Political Economy Smith’s Wealth of Nations was used as a text-book. Being a close disciple of this great economist, Dew was naturally a firm adherent to the policy of Free Trade. In the United States the two great parties were then, as now, divided on the subject of tariffs. Thus Dew-to use his own words–_”convinced of the error and impolicy of the Restrictive System, and having seen the excitement which it had occasioned, and hoping that a calm and dispassionate view of the subject would be of some profit,” published in 1829 his treatise on the “Restrictive System.” This was in the form of lectures which were written for, and delivered to, his senior class in political science. However unprejudiced and non-partisan Dew announces himself to be, and no doubt aimed to be, one readily sees that it is an attack upon the Restrictive System, and that its author was a radical Anti-Tariff man.

The argument is logical and forcible. He combined theoretical and practical views, and aimed to make the treatise fair and unprejudiced, “being convinced that it is the great duty of the Professor to inculcate upon the mind of the student those general principles alone, which will form the basis of his future opinions and actions.”

To Dew politics was something eminently practical, and he expresses this clearly in closing this treatise, urging that it is the duty of every American citizen, especially of such as enjoy the privileges of education, to prepare himself for the part which may devolve upon him, “and a laudable ambition should make you look to yourselves as the philosophers and statesmen of other days.”

This treatise, although written for his class, was widely read, particularly throughout the South, where it coincided with the political views of most voters. In the North it was also well received. Its logic was irresistible and conclusive, and it is believed to have exerted a great influence in the remodeling of the tariff laws in 1832.

Another large work of Dew’s was a “Digest of the Laws, Customs, Manners, and Institutions of the Ancient and Modern Nations.” This also was written for his classes in the History Department. It was printed and used in his classes, but was not published until after his death. It has no pretensions of originality, but has decided advantages over most historical compilations of the time. This was also written in the lecture style and is, rather than an enumeration of facts and events, a digest of the subjects named in the title. Its topical method of treatment and the life which the author has infused into it, make it very interesting and agreeable reading. Being suggestive of parallels between ancient and modern history and politics, it was a practical application of the lessons of past history to the needs of the American youth.

Primarily Dew was a teacher, but this did not prevent him from taking an active part in the political life of his day. We have already noted his influence in regard to the tariff, but far more than this was his influence upon the question of slavery. The evil of the institution had long been recognized, both in the North and in the South; in fact, there had never been a time when it was not bitterly opposed. Thomas Jefferson had devoted a great part of his life in an effort to perfect some means whereby the slave system could be done away with. In Virginia such men as George Wythe, St. George Tucker, and John Randolph had done much to establish the spirit of philanthropy prevalent in Virginia before the onslaught of the Abolitionists.

Benjamin Lundy, the editor of an emancipation paper published in Baltimore, had done much in the interest of emancipation in the South. In 1829 there were several organizations in the South founded upon a moral dissatisfaction with slavery. However, with the abuses and incriminations of Garrison, who had taken charge and turned the direction of Lundy’s paper, the whole tide set in and the benefits of slavery, socially, politically, and economically were preached in Virginia by Dew, and in South Carolina by William Gillmore Simms. Simms edited a volume, “The Pro-Slavery Argument,” in which Prof. Dew, Chancellor Harper and ex-Gov. Hammond, of South Carolina, were his fellow contributors. Simms argued the “divine right” of slavery; Dew, the economic and social benefits.

In this argument Dew showed that it was to Virginia’s advantage to raise slaves, and that trade in slaves had been one of Virginia’s chief sources of wealth and profit. Dew propounds two questions: “Can these two distinct races of people now living together as master and servant, be ever separated ?” and, “Will the day ever arrive when the black can be liberated from his thraldom and mount upward in the scale of civilization and rights to an equality with the white?” With an argument full of illustrations and deductions from law and history he essays that such a consummation would be both undesirable and impossible. That Dew’s sense of justice was hidden by his interest in his State, or at least in the white population of it, is shown in the conclusion: “There is a slave property of the value of $100,000,000 in Virginia, and it matters but little how you destroy it, when it is gone the deed is done and Virginia will be a desert.”

In August, 1830, there had occurred the slave insurrection in Southampton county, Virginia. Over fifty persons had been killed before it was put down by an armed force. The insurrection produced a strong movement of the public mind in the State and elsewhere. When the Legislature met in December, 1831, it was evident that the question of negroes, both slaves and freedmen, would be the principal subject for deliberation before this body. During the session letters and petitions were received from nearly every county in the State, from Quaker societies and other philanthropic organizations. Various bills and measures were proposed, and the discussion of the slave question was taken up day after day. At this time there appeared in the Richmond newspapers an argument in favor of slavery by Dew. This also appeared in the American Quarterly Review, and was no doubt widely read.

Whatever effect other influences might have had, we know that Dew’s argument was convincing and effectual, so that, instead of emancipating the negro, the Legislature passed stringent laws against the slaves, free negroes and mulattoes, forbidding them to hold public meetings, prescribing their education, and imposing other restrictions which now seem pitiable and entirely incompatible with a correct sense of moral justice.

In this argument Dew discussed the origin of slavery, its advantages, the various proposed plans for abolition, and finally its injustice and evils. The origin of slavery he attributed to be due to four causes, viz., the laws of war, the state of property and feebleness of government, bargain and sale, and crime. In setting forth the advantages of slavery and its aid in civilizing the world, he showed that it had been the only means of mitigating the horrors of savage warfare. Again, it had conquered the sloth and listlessness of the savage and inured him to regular industry. He illustrates this point by the fact that the only Indian tribe in America who had advanced greatly in civilization had possessed negro slaves. Moreover, as household servants, they relieved woman of all the drudgery and thus raised her in dignity and position. As for abolition, he considered that there could be but two real plans: emancipation with deportation, and emancipation without deportation. He proves the first impracticable, the second impossible.

Dew allows that slavery is wrong in the abstract and is contrary to the spirit of Christianity, but he says that if we cannot be rid of one evil without perpetrating another, then the law of God and man forbid us action. In answer to Jefferson’s charge that slavery produces deleterious moral effects, he points to the sound population of Virginia and the chivalry of the South. With the illustrations of Sparta, Thebes, Athens, Rome, and Poland, he shows that the history of the world does not prove slavery to be inconsistent or unfavorable to a republican state. Where there are black slaves the whites are equal, and this is the very essence of republicanism. He shows that there is but slight insecurity arising from the possibility of slave uprisings. He admits that under favorable conditions free labor is the best, but where love of idleness prevails slave labor is consequently the better. Our free negroes, the Indians, the Russian serfs, the Haytians, and others will not work except when compelled.

To those who pointed out that Virginia and the South were not keeping pace with northern and new western States, he argued, like the staunch free-trader that he was, that the conditions were due not to slavery, but to the fact that the Revolution had destroyed the South’s agricultural market, and that high tariff, and that alone, had restricted the growth of the South.

Of course no one to-day defends slavery, and its injustice and inhumanity is readily apparent to every thinking person, but we find it hard to criticise or condemn this man whose philanthropy was overruled by his interest in the State. It was natural that Dew should defend slavery; his education and environment had inculcated in him a firm belief in its advantages. Familiar with classic history, he looked back upon the splendor and magnificence of Rome and Greece, and he hoped to see slavery build up America even as it had built them up. To him the Roman State was ideal, the elevated condition of woman, the men, with slaves doing their work, devoting themselves to education, to art, to philosophy, and to statesmanship.

However much Dew might have otherwise been interested in politics, we know that President Jackson consulted him in regard to the Bank Bill. He appears to have had considerable influence with Jackson, and has been called a member of the famous “Kitchen Cabinet.”

Notwithstanding his great interest and activity in the affairs of the State, his great work was done in his daily life as a teacher. He was the greatest president of a college which was a maker of statesmen, a college which produced four Presidents of the United States, seventeen governors, as many senators, and nearly forty judges, not to mention a goodly number of congressmen, cabinet officers, professors, etc. He was to William and Mary what Prof. Cooper was to the College of South Carolina—a teacher whose doctrines entered into the life of the Southern people. His whole soul was wrapped up in his college, and his research into the theory of government and the great principles of political economy has made his influence felt in the history of our State.

In the summer of the year 1846 he traveled abroad for the second time. For many years his constitution had been gradually undermined by consumption, and a damp, chilling ocean voyage accelerated its ravages. On the fifth day of August, as we learn from the Paris correspondent of the Charleston Courier, he arrived in Paris accompanied by his wife, and here he died the next day. On account of the nature of the disease he was buried the day following his death, and Paris still holds the body of this great educator, a philosopher, one of the first literary men of the day, a distinguished political writer and an able essayist. In his home life Dew was of a quiet, kind and unassuming disposition, which, with his exquisite literary taste and brilliant talents, made him much respected and beloved.

I read your article on Thomas R. Dew by D. Ralph Midyette, Jr. (1886-1980). It states at the end of this article that Midyette attended “Randolph Macon College in North Carolina.” I believe that RMC has always been in Ashland, Virginia, not NC.